Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 29 PDF.Indd

Now incorporating Audicord THIS ISSUE INCLUDES: “I Love Paris” Organ Arrangement by Tony Back Profile of DirkJan Ranzijn From One Note to Another by John Everett (Part Two) Alan Ashtons Organised Keyboards The Spreckels Organ by Carol Williams The Duo Art Aeolian Organ February to April 2006 to April February Groov’in with Alan Ashton (Part Seven) Issue Twenty-Nine 1 Welcome to Issue Twenty-Nine Contents List for Issue 29: MSS Studios Top Forty Welcome / General Information 2 Our best selling CDs & DVDs from October to December 2005 Alan Ashtons Organised Keyboards 4 Compiled from magazine and website sales The Spreckels Organ by Carol Williams 11 1 Klaus Wunderlich Up, Up & Away (2CD) Profile of DirkJan Ranzijn 12 2 Doreen Chadwick Echoes of Edmonton (Offer) Ian Wolstenholme ReViews... 14 3 Robert Wolfe Over The Rainbow (Offer) From One Note to Another by John Everett (Part Two) 16 4 VARIOUS Electronic Organ Showcase (DVD) The Duo Art Aeolian Organ 18 5 Arnold Loxam Arnold Loxam: 2LS Leeds Bradford… New Organ & Keyboard DVDs 19 6 Robert Wolfe Those Were The Days 7 John Beesley Colours (Offer) Groov’in with Alan Ashton (Part Seven) 22 8 Brett Wales One Way MUSIC FEATURE: I Love Paris 29 9 DirkJan Ranzijn Live in Bournemouth (DVD) ORGAN1st Catalogue 34 10 Byron Jones My Thanks To You (DVD) ORGAN1st New Additions 52 11 Doreen Chadwick Say It With Music 12 Howard Beaumont The Best of Times www.organ.co.uk 13 Tony Stace Happy Days Are Here Again 14 Phil Kelsall Razzle Dazzle 15 Franz Lambert Wunschmelodien, Die Man Nie Verg… 16 VARIOUS Pavillioned -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

Keith Hess Appointed Vice President and Managing Director of the Guest House at Graceland

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: THE BECKWITH COMPANY David Beckwith | 323-845-9836 [email protected] Marjory Hawkins | (512) 838-6324 [email protected] KEITH HESS APPOINTED VICE PRESIDENT AND MANAGING DIRECTOR OF THE GUEST HOUSE AT GRACELAND MEMPHIS, Tenn. – February 17, 2016 – Hotel industry veteran Keith Hess has been appointed vice president and managing director of the under-construction, full-service, 450-room resort hotel, The Guest House at Graceland, which is located just steps away from Elvis Presley’s Graceland® in Memphis. The announcement was made by Jim Dina, chief operating officer of the Pyramid Hotel Group, which is managing the hotel for Elvis Presley Enterprises/Graceland. Hess brings more than 30 years of hotel and resort experience. For the past seven years, he has served as Pyramid Hotel Group’s vice president of operations, overseeing hotel and resort teams with Hilton, Hyatt, Westin, Sheraton, Marriott as well as Independent Brands. “All of us at Pyramid look forward to being part of this unprecedented, world-class resort and conference destination in the heart of Graceland,” said Dina. “We are pleased to announce Keith Hess as the managing director of The Guest House at Graceland. He is a strong leader, with a talent for cultivating and building top-notch hotel teams.” “Graceland is delighted to have Keith join us in such a key role at The Guest House at Graceland,” said Jack Soden, CEO of Elvis Presley Enterprises. “The Guest House is our most exciting project since opening Graceland in 1982, and we know that with Keith and Pyramid’s invaluable support, we’ll be providing extraordinary guest, conference, meeting and event experiences for the Memphis community and Graceland visitors from around the world.” The Guest House at Graceland is scheduled to open on October 27 of this year with a three-day gala grand opening celebration. -

Nail Salon Owner Is on a Quest to Help Ex-Felons

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Tuesday, April 20, 2021 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 136 | No. 47 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Whitehaven school’s ‘store’ rewards positive behavior DAJA E. HENRY bags of chips and basketballs to fourth-grader Jeremiah Haynes the Trailblazer Incentive Store is is a big deal to Phi Beta Sigma,” Courtesy of The Daily Memphian hoverboards and bicycles. said. The initiative started off as packed with prizes. said Dwayne Scott, chair of the Behind a royal blue ribbon and Third grader Maleek McClin- a cart stocked with candy that The goodies are for students chapter’s foundation. “We’re com- a closed door emblazoned with the ton broke out in dance, showing teachers would push around to who model positive behavior and mitted to you as long as Tau Iota school’s logo, students at Robert R. what he would do once he earned incentivize positive behavior. respect, excel in the classroom, Sigma is around. ... We are defi- Church Thursday, April 15, got to enough points for a BeyBlade. Now, after a $10,000 donation have good attendance or any nitely happy to labor with you and see for the first time a new incen- “I’m a gamer so I might as well from the Tau Iota Sigma chapter other behavior that would build tive store with prizes ranging from get a PlayStation 4 and AirPods,” of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity Inc., up their ClassDojo points. -

The Mid-South Coliseum 996 Early Maxwell Boulevard Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee

The Mid-South Coliseum 996 Early Maxwell Boulevard Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee Text by Carroll Van West, 2000 Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the Mid-South Coliseum has extraordinary local significance in the modem history of entertainment/recreation and the music history of Memphis. Developed and constructed between 1960 and 1964, the Mid-South Coliseum was the first public auditorium in Memphis to be planned as an integrated facility, rather than a so-called "separate but equal" segregated building. Performances before integrated audiences occurred there as soon as the building opened in 1964, and its period of significance extends to 1974, when Elvis Presley gave his first Memphis concerts in over a decade at the coliseum and recorded a live album there It is the only extant building In Memphis where such significant musical groups as The Beatles, The Stax-Volt Record Revue, Ike and Tina Turner, The Who, Led Zepellin, The Rolling Stones, James Brown, and Elvis Presley performed during their period of significance in American popular music and as such, the coliseum served as a center for cultural expression among Memphis youth, both white and black. Building a Modern, Integrated Coliseum in an Era of Racial Conflict Planning for a new, modern auditorium for the Mid-Sout Fairgrounds in Memphis began in late 1959. Brown v. Board of Education (1954) had been the law of the land for five years, but Memphis, like most other major Southern cities, had moved only slightly toward anything but token compliance with the end of the legal justification for Jim Crow segregation. -

62Nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No T R E Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall

62nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No t r e Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall Parking ndsp.nd.edu/ parking- and- trafǢc/visitor-guest-parking Visitor parking is available at the following locations: • Morris Inn (valet parking for $10 per day for guests of the hotel, rest aurants, and conference participants. Conference attendees should tell t he valet they are here for t he conference.) • Visitor Lot (paid parking) • Joyce & Compt on Lot s (paid parking) During regular business hours (Monday–Friday, 7a.m.–4p.m.), visitors using paid parking must purchase a permit at a pay st at ion (red arrows on map, credit cards only). The permit must be displayed face up on the driver’s side of the vehicle’s dashboard, so it is visible to parking enforcement staff. Parking is free after working hours and on weekends. Rates range from free (less than 1 hour) to $8 (4 hours or more). Campus Shut t les 2 3 Mc Kenna Hal l Fl oor Pl an Registration Open House Mai n Level Mc Kenna Hall Lobby and Recept ion Thursday, 12 a.m.–5 p.m. Department of Anthropology Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Saturday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. 2nd Floor of Corbett Family Hall Informat ion about the campus and its Thursday, 6–8 p.m. amenities is available from any of t he Corbett Family Hall is on the east side of personnel at the desk. Notre Dame Stadium. The second floor houses t he Department of Anthropology, including facilities for archaeology, Book and Vendor Room archaeometry, human osteology, and Mc Kenna Hall 112–114 bioanthropology. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

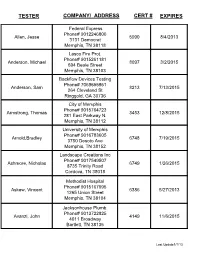

Tester Company/ Address Cert # Expires

TESTER COMPANY/ ADDRESS CERT # EXPIRES Federal Express Phone# 9012246800 Allen, Jesse 5990 8/4/2013 3131 Democrat Memphis, TN 38118 Lasco Fire Prot. Phone# 9015261181 Anderson, Michael 8097 3/2/2015 694 Beale Street Memphis, TN 38103 Backflow Devices Testing Phone# 7069655951 Anderson, Sam 8213 7/13/2015 264 Cleveland St Ringgold, GA 30736 City of Memphis Phone# 9015764723 Armstrong, Thomas 3453 12/8/2015 281 East Parkway N. Memphis, TN 38112 University of Memphis Phone# 9016783605 Arnold,Bradley 6748 7/19/2015 3750 Desoto Ave Memphis, TN 38152 Landscape Creations Inc Phone# 9017549507 Ashmore, Nicholas 6749 1/26/2015 8735 Trinity Road Cordova, TN 38018 Methodist Hospital Phone# 9015167095 Askew, Vincent 6386 5/27/2013 1265 Union Street Memphis, TN 38104 Jacksonhouse Plumb. Phone# 9013722825 Avanzi, John 4149 11/6/2015 4011 Broadway Bartlett, TN 38135 Last Update1/1/13 TESTER COMPANY/ ADDRESS CERT # EXPIRES Upchurch Services Phone# 9013880333 Avanzi, Steve 2941 6/12/2015 1792 Dancy Boulevard Horn Lake, MS 38637 Shelby Co. Codes Phone# 9013794340 Bain, Barry 7728 3/16/2014 6465 Mullins Station Memphis, TN 38134 Autozone Phone# 9014956563 Baker, David A. 6881 11/16/2014 123 S. Front Street Memphis, TN 38103 Trip Trezevant Inc Phone# 9017535900 Baker, Michael 8285 9/27/2015 7092 Poplar Ave Germantown, TN 38138 Tim Baker Plumbing Phone# 9015531524 Baker, Timothy 9160 Highway 64, Ste12, 4303 1/21/2013 #152 Lakeland, TN 38002 City of Germantown Phone# 9017577260 Bales, Dennis W. 8015 1/13/2015 7700 Southern Ave Germantown, TN 38138 Memphis LG&W Phone# 9015287757 Baxter, Felicia 7397 2/12/2013 220 S. -

TIME to PAY YOUR 2011-12 DPHA DUES It Is Time to Renew Your Davies Plantation Homeowners Association Memberships for 2011-12

June, 2011 Volume 16 , Issue 2 DPHA Annual Picnic date changed due to rain see you all June 12 on the grounds of Hillwood from 4-8 The annual DPHA Neighborhood picnic is not just lots of fun, it also helps build safer, friendlier communities by promoting the opportunity for neighbors to get to know each other. Pony rides, paint ball, train rides, balloon man, petting zoo, face painting, games and more 4:00 to 6: 00 pm * Free tour of Davies Manor House 4:00 to 6:00 pm * Bartlett Community Band Concert 5:00 to 6:00 pm * Live Music - Web Dalton Band 6:00 to 8:00 pm Web Dalton has opened for Garth Brooks, Randy Travis, George Strait, Jerry Lee Lewis, Charley Rich, George Jones and many more. www.Reverbnation.com/WebbDalton He performs regularly on Beale Street. Hamburgers, hotdogs, and drinks will be for sale or bring your own picnic TIME TO PAY YOUR 2011-12 DPHA DUES It is time to renew your Davies Plantation Homeowners Association Memberships for 2011-12. Dues expire on March 31st each year and therefore should be renewed by April 1st. Annual dues are ONLY $30.00 Please make checks payable to DPHA and mail to: Julie Olsen, DPHA Treasurer 8940 Daisy Ellen Cove Bartlett, TN 38133-3865 If there are any changes to your E-mail address or telephone number please complete the Membership Form on the back of this newsletter, indicate any changes, and include this with your $30 dues check. If you are not sure if you have paid your dues for this year, please call (377-3390)or E-Mail Julie Olsen, DPHA Treasurer [email protected] before you mail your check. -

Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting

Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting March 2016 Committee Members T. Prendergast, Chair F. Ferrer R. Bickford A. Cappelli S. Metzger J. Molloy M. Pally J. Sedore V. Tessitore C. Wortendyke N. Zuckerman Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20th Floor Board Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 3/21/2016 1:45 - 2:45 PM ET 1. PUBLIC COMMENTS PERIOD 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES February 22, 2016 - Minutes from February '16 - Page 3 3. COMMITTEE WORK PLAN - 2016-2017 CPOC Committee Work Plan - Page 6 4. QUARTERLY MTA CAPITAL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY UPDATE - Progress Report on Second Avenue Subway - Page 8 - IEC Project Review on Second Avenue Subway - Page 17 - Second Avenue Subway Appendix - Page 22 - Progress Report on East Side Access - Page 23 - IEC Project Review on East Side Access - Page 33 - East Side Access Appendix - Page 39 - Progress Report on Cortlandt Street #1 Line - Page 40 - IEC Project Review on Cortlandt Street #1 Line - Page 47 5. CAPITAL PROGRAM STATUS - Commitments, Completions, and Funding Report - Page 51 6. QUARTERLY TRAFFIC LIGHT REPORTS - Fourth Quarter Traffic Light Reports - Page 59 7. QUARTERLY CAPITAL CHANGE ORDER REPORT (for information only) - CPOC Change Order Report - All Agencies - Page 118 Date of next meeting: Monday, April 18, 2016 at 1:15 PM MINUTES OF MEETING MTA CAPITAL PROGRAM OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE February 22, 2016 New York, New York 1:15 P.M. MTA CPOC members present: Hon. Thomas Prendergast Hon. Fernando Ferrer Hon. Susan Metzger Hon. John Molloy Hon. Mitchell Pally Hon. James Sedore Hon. Carl Wortendyke MTA CPOC members not present: Hon. -

Nonconnah's Polluted Water Likely Leaking Into Memphis Aquifer

PRINT EDITION JUST $99 PER YEAR Covering local news, politics, and more Covering Memphis Since 1886 Channel 10 Friday nights at 7 MEMPHISDAILYNEWS.COM Wednesday, August 7, 2019 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 134 | No. 125 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Mid-South Transplant Foundation takes message to pews JANE ROBERTS instigating some friendly compe- to sign up at least 10 by Labor Day.” and organ availability is a justice so to speak.” Courtesy of The Daily Memphian tition between African-American At Olivet Fellowship Baptist issue for a community that suffers Probably no one has more skin The reasons are many and congregations, hoping to up the Church, the Rev. Eugene Gibson more genetic disease and gang in the game than Brown Mission- historic. African-Americans, who ante. expected 6-10 parishioners would violence than any ethnic group in ary Baptist Church on Swinnea in the Mid-South are waiting in “The GiveLife10 campaign is sign up last Sunday. “It was awe- the nation. in Southaven. Sunday, the Rev. greater numbers than any other all about encouraging churches to some,” he said. “We had 23 people “If we complain about what is Bartholomew Orr hadn’t been at group for kidneys and livers, are increase the number of registered register. I think we are doing our going on, what is our part of the the pulpit 10 minutes before he underrepresented in organ do- tissue and organ donors,” said part.” solution? One of the ways we can was taking his donor card out of nor registries. This month, Mid- Randa Lipman, manager of com- For Gibson, longtime member fix this is become a donor yourself his wallet.