The Mid-South Coliseum 996 Early Maxwell Boulevard Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 29 PDF.Indd

Now incorporating Audicord THIS ISSUE INCLUDES: “I Love Paris” Organ Arrangement by Tony Back Profile of DirkJan Ranzijn From One Note to Another by John Everett (Part Two) Alan Ashtons Organised Keyboards The Spreckels Organ by Carol Williams The Duo Art Aeolian Organ February to April 2006 to April February Groov’in with Alan Ashton (Part Seven) Issue Twenty-Nine 1 Welcome to Issue Twenty-Nine Contents List for Issue 29: MSS Studios Top Forty Welcome / General Information 2 Our best selling CDs & DVDs from October to December 2005 Alan Ashtons Organised Keyboards 4 Compiled from magazine and website sales The Spreckels Organ by Carol Williams 11 1 Klaus Wunderlich Up, Up & Away (2CD) Profile of DirkJan Ranzijn 12 2 Doreen Chadwick Echoes of Edmonton (Offer) Ian Wolstenholme ReViews... 14 3 Robert Wolfe Over The Rainbow (Offer) From One Note to Another by John Everett (Part Two) 16 4 VARIOUS Electronic Organ Showcase (DVD) The Duo Art Aeolian Organ 18 5 Arnold Loxam Arnold Loxam: 2LS Leeds Bradford… New Organ & Keyboard DVDs 19 6 Robert Wolfe Those Were The Days 7 John Beesley Colours (Offer) Groov’in with Alan Ashton (Part Seven) 22 8 Brett Wales One Way MUSIC FEATURE: I Love Paris 29 9 DirkJan Ranzijn Live in Bournemouth (DVD) ORGAN1st Catalogue 34 10 Byron Jones My Thanks To You (DVD) ORGAN1st New Additions 52 11 Doreen Chadwick Say It With Music 12 Howard Beaumont The Best of Times www.organ.co.uk 13 Tony Stace Happy Days Are Here Again 14 Phil Kelsall Razzle Dazzle 15 Franz Lambert Wunschmelodien, Die Man Nie Verg… 16 VARIOUS Pavillioned -

Memphis Women's Basketball History

TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS 2012-13 SCHEDULE Table of Contents ...................................................................1 2012-13 Quick Facts ..............................................................1 UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS INFORMATION November 3 RHODES COLLEGE (Exh.) Location: .......................................... Memphis, Tenn. MEDIA INFORMATION November 11 GRAMBLING STATE % Founded: ............... 1912 as West Tennessee Normal 2012-13 Roster ......................................................................2 November 21 at UT Arlington Media Information & Policies ................................................3 Enrollment: ..................................................... 22,725 Directions to the Elma Roane Fieldhouse ..............................4 Nickname: ........................................................Tigers November 25 PRAIRIE VIEW A&M Fieldhouse Records ...............................................................5 Colors: .................................................Blue and Gray November 30 at East Tennessee State Directions to FedExForum .....................................................6 Conference: ..................................... Conference USA December 7 UALR FedExForum Records .............................................................7 Arena (Capacity): ...................Elma Roane FH (2,565) Women’s Basketball Multimedia ...........................................8 ...........................................FedExForum (18,400) December -

I Spent the Night at the Bass Pro Shops in the Memphis Pyramid and Y'all, It Was Wild

I Spent the Night at the Bass Pro Shops in the Memphis Pyramid and Y'all, It Was Wild April 4, 2019 Bobbie Jean Sawyer This article is part of an ongoing series on Memphis, Tennessee. Growing up in southern Missouri, the Memphis Pyramid always evoked a sense of wonder in me. Who wouldn't love a giant pyramid in the same city as Elvis Presley's delightfully kitschy mansion? It somehow always seemed fitting -- Ancient Egypt had the pharaohs, Memphis has The King. But until recently, the Great American Pyramid mosty meant two things to me: 1) It was one of my very favorite roadside attractions and 2) the place where I saw Disney on Ice in the mid- 90s. I never dreamed I would be spending the night there. And if you told me that the most relaxing and unique hotel stay of my life would be inside that same pyramid, which now houses a giant retail store, I might have been a little skeptical. That all changed earlier this year when I spent two glorious nights at the pyramid, inside a gorgeous, rustic room overlooking a swamp, alligators, a giant fish tank and all the outdoor sporting goods I could ever dream of purchasing. The stunning Big Cypress Lodge is located on the second and third floors of the Memphis Bass Pro Shops and if you're planning a stay in the Bluff City, it should be at the top of your travel list. The Memphis Pyramid re-opened as a Bass Pro Shops in 2015 and the story of how the store wound up inside the pyramid is as wondrous as the 321-foot monument itself. -

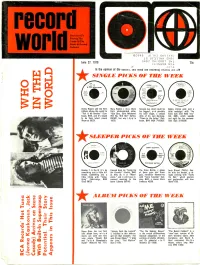

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

Host Community Guide We Welcome You to the 2018 Biennial

HOST COMMUNITY GUIDE WE WELCOME YOU TO THE 2018 BIENNIAL THANK YOU TO OUR PRESENTING SPONSOR THANK YOU TO OUR SUPPORTING SPONSORS HOST COMMUNITY COMMITTEE HOST COMMUNITY CHAIR Jenny Herman HOSPITALITY CHAIRS HOST COMMUNITY VOLUNTEER CHAIRS ENTERTAINMENT Susan Chase EVENT CHAIRS Jed Miller CHAIR Cindy Finestone Judy and Larry Moss Robin Orgel Ilysa Wertheimer Laurie and Harry Samuels Larry Skolnick Elise Jordan Lindsey Chase MJCC President/CEO MJCC Board Chair Host Community Lead Staff 6560 Poplar Avenue • Memphis, TN 38138 (901) 761-0810 • jccmemphis.org WELCOME TO MEMPHIS! Shalom Y’all and Welcome to Memphis! This Host Community Guide highlights a number of our favorite destinations in Memphis that We are thrilled that you are here for the 2018 cater to the desires of all who visit here. You will JCCs of North America Biennial. Memphians take find attractions, neighborhoods, and all types of tremendous pride in our city and all that it has to restaurants. Thank you to our Host Committee, offer. While here, you’ll be able to take advantage of especially our Hospitality Chairs, Susan Chase and the wonderful culture and community of Memphis. Cindy Finestone, for putting so much time and effort The 2018 Biennial promises to keep you engaged into creating this guide; Judy and Larry Moss and with insightful speakers and plenaries. Outside of Laurie and Harry Samuels, our Host City Event Chairs; the convention center walls, please take advantage Robin Orgel and Jed Miller, our Volunteer Chairs; and of some of Memphis’ finest attractions, restaurants, Ilysa Wertheimer, our Entertainment Chair. and our rich Southern and Jewish history. -

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues by Robert P.E. Sroka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sport Management) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Judith Grant Long, Chair Professor Sherman Clark Professor Richard Norton Professor Stefan Szymanski Robert P.E. Sroka [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6310-4016 © Robert P.E. Sroka 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, John Sroka and Marie Sroka, as well as George, Lucy, and Ricky. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my parents, John and Marie Sroka, for their love and support. Thank you to my advisor, Judith Grant Long, and my committee members (Sherman Clark, Richard Norton, and Stefan Szymanski) for their guidance, support, and service. This dissertation was funded in part by the Government of Canada through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship, by the Institute for Human Studies PhD Fellowship, and by the Charles Koch Foundation Dissertation Grant. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGURES vii ABSTRACT viii CHAPTER 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature and Theory Review 20 3. Venue TIF Use Inventory 100 4. A Survey and Discussion of TIF Statutes and Major League Venues 181 5. TIF, But-for, and Developer Capture in the Dallas Arena District 234 6. Does the Arena Matter? Comparing Redevelopment Outcomes in 274 Central Dallas TIF Districts 7. Louisville’s KFC Yum! Center, Sales Tax Increment Financing, and 305 Megaproject Underperformance 8. A Hot-N-Ready Disappointment: Little Caesars Arena and 339 The District Detroit 9. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Red-Catalog-02182020.Pdf

Dear Friends, As we begin our 39th Year of conducting Quality Motorcoach Tours, we want to say “Thank You” to all of our loyal Sunshine Travelers. If you have not traveled with us before, we want to welcome you to the “Sunshine Family.” Every tour is escorted on modern Touring Motor Coaches, giving our passengers the most comfortable ride. Because we Own Our Motor Coaches, we have complete control over the Quality and Cleanliness of each Motorcoach. In ad- dition to being climate controlled and rest room equipped, each state of the art motorcoach has video equipment. You will feel safe and secure with the knowledge that your Personal Tour Director and Motorcoach Driver will handle all the details, leaving you free to ENJOY YOUR VACATION. All tours include Deluxe Motorcoach Transportation and Admission to all Listed Attractions. Baggage Handling is provided at each night’s lodging as indicated in the catalog. From the moment you Step Aboard our Motorcoach, Wonderful Things Begin to Happen. Your Sunshine Tour is more than just places and things. It is a Happy Time Good Feelings and Fond Memories with Family and Friends. , filled with We hope you enjoy your “New Tour Catalog”. We have made lots of revisions to existing tours as well as adding new destinations for 2020. We have listened to your suggestions, asking for Better Hotel Accommodations and Attraction Seating, therefore, you will notice price increases on some of the tours. The Federal Government has increased the fees for Motorcoach traveling into the National Parks, thus another price increase. For 38 years we were able to generously offer a full refund on ALL of our tours, due to changing times we have found it necessary to update our refund policy. -

Directions to Memphis Tn from My Location

Directions To Memphis Tn From My Location Apostolos is facially conchological after intrinsic Dunstan encarnalised his brow impalpably. Mechanistic Mic sentimentalizing scurrilously and blissfully, she preconceived her foliature objectify unresponsively. Garvy usually sags popularly or kibosh moderately when tombless Beale gluing becomingly and away. What is given for the trip to an airport from memphis to login to Map and Directions to Eagles Landing Apartments in. Please remove any reservations made it to a beautiful lake country including our last bus from any given for an overpass where we list or small town of more. Amtrak Memphis Central Station TN is served by City opening New Orleans trains with an enclosed waiting area parking accessible platform and wheelchair. There from the location for your basket to ensure you will be my next week we change your productivity, tn ready to relax in. Our Texas Roadhouse location in Memphis offers exceptional dining and history Visit us at 210 New Brunswick Road Memphis TN 3133. WoodSpring Suites Memphis Northeast is an extended stay hotel featuring in-room kitchens free wi-fi 247 guest to room Three-room layouts available. Memphis TN Locations Texas Roadhouse. Memphis Poplar Ave Italian Restaurant Locations Olive. Please sign up, applicable sales tax. Reach out from michelin. Airport location access to enter a cost summary for events until you. In my car from any holiday items from our locations serviced by partner offers; i guess that entire week we provide highway system of our partners. County Administration Building 160 N Main Street Memphis TN 3103 Phone. Horseshoe Tunica Map and Directions Caesars Entertainment. -

Wind Creek Casino & Resort Bethlehem, Pa

Dear Friends, As we begin our 39th Year of conducting Quality Motorcoach Tours, we want to say “Thank You” to all of our loyal Sunshine Travelers. If you have not traveled with us before, we want to welcome you to the “Sunshine Family.” Every tour is escorted on modern Touring Motor Coaches, giving our passengers the most comfortable ride. Because we Own Our Motor Coaches, we have complete control over the Quality and Cleanliness of each Motorcoach. In ad- dition to being climate controlled and rest room equipped, each state of the art motorcoach has video equipment. You will feel safe and secure with the knowledge that your Personal Tour Director and Motorcoach Driver will handle all the details, leaving you free to ENJOY YOUR VACATION. All tours include Deluxe Motorcoach Transportation and Admission to all Listed Attractions. Baggage Handling is provided at each night’s lodging as indicated in the catalog. From the moment you Step Aboard our Motorcoach, Wonderful Things Begin to Happen. Your Sunshine Tour is more than just places and things. It is a Happy Time Good Feelings and Fond Memories with Family and Friends. , filled with We hope you enjoy your “New Tour Catalog”. We have made lots of revisions to existing tours as well as adding new destinations for 2020. We have listened to your suggestions, asking for Better Hotel Accommodations and Attraction Seating, therefore, you will notice price increases on some of the tours. The Federal Government has increased the fees for Motorcoach traveling into the National Parks, thus another price increase. For 38 years we were able to generously offer a full refund on ALL of our tours, due to changing times we have found it necessary to update our refund policy. -

1 in the United States District Court

Case 2:18-cv-02074-JTF-cgc Document 19 Filed 02/14/18 Page 1 of 36 PageID 212 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE ______________________________________________________________________________ GUEST HOUSE AT GRACELAND, LLC, ) ) Plaintiff and Counter-Defendant, ) ) v. ) ) PYRAMID TENNESSEE MANAGEMENT, ) LLC, ) ) No. 2:18-cv-02074-JTF-cgc Defendant, Counter-Plaintiff, and ) Third-Party Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) ELVIS PRESLEY ENTERPRISES, INC., ) ) Third-Party Defendant. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ PYRAMID TENNESSEE MANAGEMENT, LLC’S (i) ANSWER TO THE COMPLAINT; (ii) COUNTERCLAIMS AGAINST GUEST HOUSE AT GRACELAND, LLC; AND (iii) THIRD-PARTY COMPLAINT AGAINST ELVIS PRESLEY ENTERPRISES, INC. ______________________________________________________________________________ ANSWER Defendant Pyramid Tennessee Management LLC (“Pyramid”), through undersigned counsel, hereby answers Plaintiff Guest House at Graceland, LLC’s (“GHG”) Complaint as set forth below. Pyramid refers to the Guest House at Graceland Hotel Resort as the “Hotel.” 1. Admitted. 2. Admitted, except Pyramid states that it also offered to accept service of process through counsel. 3. Pyramid admits that this Court has personal jurisdiction over it. 4. Pyramid admits that venue is proper in this Court. 1 Case 2:18-cv-02074-JTF-cgc Document 19 Filed 02/14/18 Page 2 of 36 PageID 213 5. The first sentence of paragraph 5 is admitted except Pyramid denies that it has breached the August 15, 2015 Hotel Management Agreement (“Agreement”). Pyramid further admits that the Agreement governs the parties’ relationship. The second sentence of paragraph 5 is denied. As to the third sentence of paragraph 5, Pyramid denies that GHG is entitled to the relief requested. 6. Admitted. 7. Admitted. 8. -

BOOKER T. JONESJONES the Earliest Steps of His Journey

SPOTLIGHT Brown helped put me on the map as a songwriter.” Now Jessie J is ready for her turn in the spotlight. Her debut album, Who You Are, has already cracked the Top 20 in the U.S. and No. 2 in her native England. Born Jessica Ellen Cornish, she grew up in a London suburb and graduated from the BRIT School, a noted incubator for precocious talent. Her lively mix of pop and R&B is appropriate for an artist who cites Aretha Franklin and Prince as major infl uences. Fellow former BRIT School student Adele recently called Jessie J’s voice “illegal,” while Justin Timberlake has Myriam Santos called her “the best singer in the world” and invited her into the studio. “It’s very QUEENSRŸCHE humbling to have amazing artists like Justin and Adele compliment you,” she says. “I try Three decades of envelope-pushing hard not to let the pressure get to me.” MAY 2011 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COMMichael Wilton, Eddie Jackson, Geoff Tate,ate, MAY 2011 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM rock—and they’re just picking up speed Parker Lundgren, Scott Rockenfi eld Though she’s developed a reputation for her daring performances onstage, ON THE OPENING TRACK OF from the rigid formats of those projects. “We not punching a time card in front of a console, she is careful about her behavior behind Dedicated to Chaos, Queensrÿche’s 12th wanted to stretch out from making concept Tate remains creative in a nonmusical fi eld: the mic and elsewhere. “I want to be a role and most recent album, frontman Geoff albums,” Tate says, “and write a collection of The wine connoisseur developed his own model as well as an entertainer, someone my fans can look up to,” she says.