The Late Intermediate Period Occupation of Pukara, Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quispe Pacco Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL DISTRITO DE NUÑOA TESIS PRESENTADA POR: SANDRO QUISPE PACCO PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN EDUCACIÓN CON MENCIÓN EN LA ESPECIALIDAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES PROMOCIÓN 2016- II PUNO- PERÚ 2017 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SEUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL D ���.r NUÑOA SANDRO QUISPE PACCO APROBADA POR EL SIGUIENTE JURADO: PRESIDENTE e;- • -- PRIMER MIEMBRO --------------------- > '" ... _:J&ª··--·--••__--s;; E • Dr. Jorge Alfredo Ortiz Del Carpio SEGUNDO MIEMBRO --------M--.-S--c--. --R--e-b-�eca Alano�ca G�u�tiérre-z-- -----�--- f DIRECTOR ASESOR ------------------ , M.Sc. Lor-- �VÍlmore Lovón -L-o--v-ó--n-- ------------- Área: Disciplinas Científicas Tema: Patrimonio Histórico Cultural DEDICATORIA Dedico este informe de investigación a Dios, a mi madre por su apoyo incondicional, durante estos años de estudio en el nivel pregrado en la UNA - Puno. Para todos con los que comparto el día a día, a ellos hago la dedicatoria. 2 AGRADECIMIENTO Mi principal agradecimiento a la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano – Puno primera casa superior de estudios de la región de Puno. A la Facultad de Educación, en especial a los docentes de la especialidad de Ciencias Sociales, que han sido parte de nuestro crecimiento personal y profesional. A mi familia por haberme apoyado económica y moralmente en -

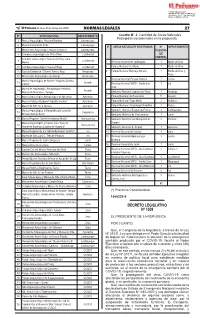

27 Normas Legales Decreto Legislativo Nº 1508

Lunes 11 de mayo de 2020 El Peruano / NORMAS LEGALES 27 N° SITIO CULTURAL DEPARTAMENTO Cuadro N° 2: Cantidad de Áreas Naturales Protegidas consideradas en la propuesta: 5 Museo Arqueológico Nacional Bruning Lambayeque 6 Museo Nacional de Sicán Lambayeque N° AREAS NATURALES PROTEGIDAS N° DEPARTAMENTO 7 Monumento Arqueológico Huaca Ventarrón Lambayeque PUESTOS 8 Complejo arqueológico de Chan Chan La Libertad DE CONTROL Complejo Arqueológico Huacas del Sol y Luna - 9 La Libertad Moche 1 Reserva Nacional de Tambopata 3 Madre de Dios 10 Complejo Arqueológico Huaca el Brujo La Libertad 2 Parque Nacional del Manu 7 Madre de Dios 11 Sala de Exhibición “Gilberto Tenorio Ruiz” Amazonas 3 Parque Nacional Bahuaja Sonene 4 Madre de Dios y Puno 12 Monumento Arqueológico de Kuélap Amazonas 4 Reserva Nacional Pacaya Samiria 7 Loreto Museo Arqueológico de Ancash “Augusto Soriano 13 Ancash Infante” 5 Reserva Nacional SIIPG - Punta San 1 Ica Juan Museo de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia 14 Ancash Natural de Ranrairca - Yungay 6 Santuario Nacional Lagunas de Mejia 1 Arequipa 15 Museo Arqueológico Antropológico de Apurímac Apurímac 7 Parque Nacional de Huascaran 11 Ancash 16 Museo Histórico Regional “Hipólito Unanue” Ayacucho 8 Parque Nacional Tingo Maria 2 Huánuco 17 Museo de Sitio de la Quinua Ayacucho 9 Parque Nacional Yanachaga Chemillen 3 Pasco Museo Arqueológico y Etnográfico del conjunto 10 Santuario Histórico Bosque de Pomac 3 Lambayeque 18 Cajamarca Monumental de Belén 11 Santuario Histórico de Chacamarca 1 Junín 19 Museo Regional “Daniel Hernández Murillo” Huancavelica 12 Santuario Nacional Los Manglares de 2 Tumbes Museo Arqueológico y Palacio Inka “Samuel Tumbes 20 Huancavelica Humberto Espinoza Lozano de Huaytará” 13 Santuario Nacional de Ampay 1 Apurímac 21 Museo Regional de Ica “Adolfo Bermudez Jenkins” Ica 14 Reserva Nacional de Lachay 1 Lima 22 Museo de Sitio Julio C. -

Peru the Richest Country in the World

WELCOME TO PERU THE RICHEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD ORLD W TR O A L V L E E SEE L H INSIDE FOR OFFERS E PROMPERÚ / Vallejos César © X E C L U S I V ON SALE UNTIL 30 APRIL 2019 A COUNTRY BLESSED WITH A UNIQUE HERITAGE, WHERE RICHES ARE MEASURED IN WELL-BEING AND HARMONY WITH NATURE. Have you ever dreamt about getting to know the magnificent Pacific Coast, contemplated the infinite beauty of the Andes and feeling the exuberance of the Amazon jungle? Peru offers all this and more - a land filled with myths and traditions, spectacular landscapes, colonial architecture and dramatic archaeological wonders. Rainbow Mountain Thanks to the legacy of powerful ancient civilizations, Peru is home to over 5,000 archaeological sites. Many of them are ADVENTURE shrouded in mystery and are able to transport the visitor back A paradise for those passionate about the adventurous side to a time when these cultures flourished. of life. Peru offers an impressive playground from trekking to mountain biking, surfing to para-gliding and canoeing to kayaking, just to name a few. With beautiful lagoons, impressive mountain ranges and the deepest canyons on the planet, Peru’s natural elements are sure to exceed the expectations of all levels of adventurers. © Carlos Ibarra / PROMPERÚ ANCIENT & COLONIAL CITIES This small, but fiercely proud country, has a rich and fascinating history of Inca kings and Spanish conquistadors. The country is dotted with the remnants of ancient cities, temples, and fortresses. Machu Picchu is the most famous NATURE of these Inca cities, while neighbouring Sacsayhuaman, Peru is synonymous with nature and has one of the greatest Ollantaytambo and Moray also draw impressive crowds. -

Visitantes Del Museo De La Inquisición

ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DE LOS MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ (1992 - 2018) ÍI,� tq -- ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DEL MUSEO DEL CONGRESO Y DE LA INQUISICIÓN Y DE LOS PRINCIPALES MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ ÍNDICE Introducción P. 2 Historia del Museo Nacional del Perú P. 3 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 19 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo Nacional Afroperuano del P. 22 Congreso Estadísticas del Sitio Web del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 23 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 29 Estadísticas de visitantes del Palacio Legislativo P. 40 Estadísticas de visitantes de los principales museos y sitios P. 42 arqueológicos del Perú 1 INTRODUCCIÓN El Museo del Congreso tiene como misión investigar, conservar, exhibir y difundir la Historia del Congreso de la República y el Patrimonio Cultural a su cargo. Actualmente, según lo dispuesto por la Mesa Directiva del Congreso de la República, a través del Acuerdo de Mesa N° 139-2016-2017/MESA-CR, comprende dos museos: Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición Fue establecido el 26 de julio de 1968. Está ubicado en la quinta cuadra del Jr. Junín s/n, en el Cercado de Lima. Funciona en el antiguo local del Senado Nacional, el que durante el Virreinato había servido de sede al Tribunal de la Inquisición. El edificio es un Monumento Nacional y forma parte del patrimonio cultural del país. Además, ha estado vinculado al Congreso de la República desde los días del primer Congreso Constituyente del Perú, cuando en sus ambientes se reunían sus miembros, alojándose inclusive en él numerosos Diputados. -

Landforms of Titicaca Near Sillustani Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Landforms of Titicaca Near Sillustani Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Torino, Italy, 2010 This book is dedicated to my grandmother, Carolina Dastrù. Amelia Carolina Sparavigna is assistant professor from 1993 at the Polytechnic of Torino, Italy. She gained her Bachelor Degree in Physics from the University of Torino in 1982, and the Doctoral Degree in 1990. She is co-author of more than 80 publications on international journals. Her research activity is on subjects of the condensed matter physics, liquid crystal microscopy and image processing. She has a passion for archaeology. Editore: Lulu.com Copyright: © 2010 A.C.Sparavigna, Standard Copyright License Lingua: English Paese: Italia Terraced hills, a network of earthworks, sometimes creating geoglyphs, and ancient ruins are the structures we can observe with the satellites imagery of Google Maps. After the previous publications on the earthworks and geoglyphs 1, let us survey specific area with more details. Here we show satellite imagery, enhanced with freely available image processing software, of the area near Sillustani, the peninsula of the Laguna Umayo, in Puno region of Peru. Besides Sillustani, interesting places are the Mesa Isla, Atuncalla and Machacmarca. The images we show are coming from the Google Maps (in few cases from the ACME Google service). The coordinates are inserted in the images, and also the scales. Sillustani is the peninsula marked with the white label in the figure. At the top of the peninsula there is a tall chullpa, about 12m high. According to scholars, Sillustani is a pre-Incan burial. Tombs are built above ground in tower-like structures called chullpas. -

HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN DE ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS PUNO [email protected] "FERIADO 28 Y 29 DE JULIO - FIESTAS PATRIAS" (051) 365088

IPERÚ Puno Esquina Jr. Deustua con Jr. Lima s/n Plaza de Armas HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN DE ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS PUNO [email protected] "FERIADO 28 Y 29 DE JULIO - FIESTAS PATRIAS" (051) 365088 HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN ACCESO PARA DISTRITO ATRACTIVO DESCRIPCIÓN DIRECCIÓN ACCESO TELÉFONO TARIFA DE ENTRADA OBSERVACIONES DISCAPACITADOS LUNES 28 MARTES 29 Extranjero: S/ 15.00 Perteneció al pintor Alemán Carlos Dreyer, Visita guiada. Exhibición de Estudiante extranjero: S/ posee interesantes colecciones de oro y plata, objetos desde la época Museo Municipal Jr. Conde de Lemos 966172717 10.00 Atenderá con alfarería y tejidos, es también el guardián de A pie No atenderá preincaica, cuenta con ocho salas Carlos Dreyer Nº 289 (Administrador) Nacional: S/ 5.00 normalidad una importante colección de cerámicas, una de ellas exhibe el tesoro de Poblador local: S/ 2.00 orfebrería y esculturas líticas pre-incas. Sillustani. Estudiantes o niños: S/1.00 Av. Es el barco de hierro más antiguo del mundo Sesquicentenario N° El buque Museo ofrece servicios que funciona con una sola hélice. Este buque 610, Sector Huaje ( Taxi y Atenderá con Atenderá con de alojamiento, cafetería Buque Museo Yavarí 051 - 369329 Voluntario contiene piezas originales, armarios y equipos Muelle del Hotel colectivos normalidad normalidad (desayunador), y servicios de navegación. Sonesta Posada del higiénicos, Inca) Una pequeña exposición sobre la navegación de maquinas de hierro en el Lago Titicaca. Se encuentra todo el relato de documentos de la historia marítima, como la historia del origen del Lago Titicaca desde las épocas incaicas, Exhibición de maquetas y colonial, independencia, contemporánea, Av. -

Ancient Aliens Tour Paititi 2016 Englisch

HIGHLIGHTS Lima „City of the Kings“ Paracs, Candelabro, the Ballestas Islands, elongated Skulls & the Alien-Skulls The engraved stones of Ica Nazca Lines, Cahuachi and the aqueducts of Cantalloc Machu Picchu Nazca Lines Pampas Galeras, The Pyramids of Sondor, the Monolith of Sayhuite & the Moon-Portal in Quillarumiyoc Cusco, navel of the world and the Sacred Valley of the Incas Saqsayhuaman, Ollantaytambo, Pisac und Machu Picchu Tipon, Andahuaylillas & the Alien-Mummy Pucara, Sillustani, Cutimbo and Chullpas of Sillustani "The Ica Stones" - Museo Cabrera it’s connections to Gobekli Tepe, Egypt, Greece, Italy and Southern Germany Copacabana, Sun Island, La Paz Tiahunaco, Puma Punku & the “Stargate” of Amaru Muro Breathtaking landscapes, nature, culture, colourful and living cultures Tiwanacu, Bolivien Tiwanaku-Idol "Cusco Alien" Culinary delicacies … E-Mail : [email protected] © by www.paititi.jimdo.com Peru is one of the most fascinating and mysterious countries on this planet. On this tour you will experience a mixture of nature, culture, breathtaking landscapes, living traditions and the unsolved enigmas of the Inca and pre-Inca cultures. On our search for tracks we’ll both take you to the well-known landmarks, for example Nasca or Machu Picchu, and to sites less known which are scarcely included by the conventional tourism. Explore with us in the land of the Inca the former empire of the “elongated skulls”, megalithic people, ancient astronauts and mountain gods. Marvel at amazing tool marks which indicate to ancient high-technologies as well as to extraterrestrial legacies, connections to Egypt, Greece, Germany or Gobekli Tepe in Turkey. A historic-archaeological side trip to Bolivia also is included. -

Durante La Ocupación Inka En Cutimbo, Puno-Perú Returning to Build: Funerary Practices and Ideology (Ies) During the Inka Occupation of Cutimbo, Puno-Peru

Regresar para construir: Prácticas funerarias e ideología(s) duranteVolumen la ocupación 38, Nº Inka… 1, 2006. Páginas 129-143129 Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena REGRESAR PARA CONSTRUIR: PRÁCTICAS FUNERARIAS E IDEOLOGÍA(S) DURANTE LA OCUPACIÓN INKA EN CUTIMBO, PUNO-PERÚ RETURNING TO BUILD: FUNERARY PRACTICES AND IDEOLOGY (IES) DURING THE INKA OCCUPATION OF CUTIMBO, PUNO-PERU Henry Tantaleán1 Este artículo describe nuestras investigaciones arqueológicas realizadas en el sitio prehispánico de Cutimbo (Puno-Perú), el mismo que fue ocupado durante el período Altiplano (1.100-1.470 d.C.) y reocupado durante la época inka (1.470-1.532 d.C.). Nuestras excavaciones se concentraron en las torres funerarias (chullpas) monumentales y sus áreas asociadas, ofreciendo evidencia de la existencia de prácticas sociales que reprodujeron asimetrías económicas, políticas e ideológicas entre Inkas y lupakas. Dicha asimetría social no sólo se dio entre la sociedad dominada (Lupaka) y la dominante (Inka), sino también en el seno de la misma sociedad Lupaka, un proceso histórico que trascendió a la ocupación inka de la zona. Palabras claves: asimetría social, coerción, ideología, lupakas, chullpas. This paper describes archaeological research carried out in Cutimbo (Puno-Peru), a prehispanic settlement occupied during the Altiplano Period (1,100-1,470 A.D.) and re-occuppied durig the Inka epoch (1,470-1,532 A.D.). Our excavations focus on the monumental funerary towers (chullpas) and related areas which offered evidence consistent with the existence of economic, political and ideological asymmetries between Inkas and lupakas. This social asymmetry not only existed between dominant society (Inka) and dominated society (Lupaka) but also within Lupaka society, a historical process trascending the Inka occupation of the area. -

Los Sarcófagos Y Los Mausoleos Preincas En Chachapoyas Pre-Inca Sarcophagi and Mausoleums in Chachapoyas

42 Los sarcófagos y los mausoleos preincas en Chachapoyas Pre-inca Sarcophagi and Mausoleums in Chachapoyas Ángela Brachetti-Tschohl Doctora en Antropología Resumen: La arquitectura funeraria de los chachapoyas de época preinca se caracteriza por la presencia de dos formas de enterramiento: el mausoleo o tumba colectiva, y el sarcófago, sepulcro unipersonal de aspecto humano. Todos los sitios funerarios, tanto de mausoleos como de sarcófagos, tienen en común el encontrarse en lugares aislados y en lo alto de las montañas, en precipicios, grutas o galerías, siendo la mayoría inaccesibles. Palabras clave: mundo andino amazónico, creencias funerarias preincas, arquitectura funera- ria, etnohistoria. Abstract: The funeral architecture of the Chachapoyas, in pre-Inca times, shows two forms of burial: the mausoleum –a collective tomb– and the sarcophagus, an individual sepulture with human shape. All the burial grounds of the mausoleums and sarcophagi have something in common: they are found in isolated places at the top of the cliffs of the mountains, most of them unreachable, in caves or underground passages. Keywords: Andean world in Amazonia, the pre-Inca funerary beliefs, funeral architecture, Ethno-history. I. La zona de Chachapoyas La región de Chachapoyas se encuentra en los Andes Amazónicos del Perú y fue conquistada, en 1475, por el inca Tupac Yupanqui, quien combatió contra la fiera resistencia de los chacha- poyas. Tupac Yupanqui quemó varias aldeas en su recorrido hacia el norte y redujo otras muchas pequeñas a lo largo del camino. Más tarde, el siguiente gobernante, el inca Huayna Capac, desterró a más pueblos de la región de Chachapoyas. Muchos de los cronistas españoles como Cieza de León (1554), Sarmiento de Gamboa (1572), Acosta (1590) o Garcilaso de la Vega (1609) mencionan la provincia de Chachapoyas en la época de la conquista española, con breves descripciones. -

Discover the Best of Peru's Andean Treks, Ancient Cultures, and Jungle

PERU The Insiders' Guide Discover the best of Peru’s Andean treks, ancient cultures, and jungle adventures with our local insiders. Contents Overview Contents The Coast Overview 3 Making the most of Machu Picchu 30 Top 10 experiences in Peru 3 Alternatives to the Inca Trail 32 Climate and weather 5 The Cordilleras 34 Where to stay 6 The Central Sierra 36 Getting around 8 Arequipa and the canyons 38 The Highlands Peruvian cuisine 10 Lake Titicaca 40 Cultural highlights 11 Language and phrases 13 The Amazon 42 Responsible tourism 14 Exploring the selva 43 Travel safety and scams 15 Visa and vaccinations 17 Adventure 45 The Amazon Hiking and trekking 46 The Coast 18 Surfing 48 48 hours in Lima 19 Rafting and kayaking 49 Trujillo and the north 21 Ica and the south 23 Essential insurance tips 51 Our contributors 53 Adventure The Highlands 25 See our other guides 53 48 hours in Cusco 26 Need an insurance quote? 54 Day trips from Cusco 28 2 Colombia Welcome! Equador Whether you’re pondering the mysteries of an advanced ancient Iquitos culture, trekking amid the Andes’ highest peaks, watching monkeys Kuelap bound through the jungle, or Chiclayo Brazil surfing a mile-long break, this Contents Trujillo diverse country never fails to Pucallpa amaze and inspire. Huanuco LIMA Machu Picchu Cusco Overview Our Insiders' Picks Ica Bolivia Puno of the Top 10 Arequipa Lake Experiences in Peru Titicaca Sample Peru’s world-class cuisine The Coast From classics like ceviche, to modern citadel of Choquequirao, which gets just takes on traditional dishes, to tasty a handful of visitors each day. -

Machu Picchu & Peru

Machu Picchu & Peru Machu Picchu June 17 - 30, 2021 & Peru Peru Itinerary Day 1 Arrive Lima Day 2 Fly to Cusco and visit Chinchero Day 3 The Sacred Valley - Urco - Sacred Ceremony June 17 - 30, 2021 Day 4 Machu Picchu Get a free copy of our Sedona Soul Day 5 Machu Picchu – “Machu Picchu & Sacred Peru” Sacred Ceremony Adventures Day 6 Machu Picchu Debra’s beautiful 24 pages (including photos) about Machu Day 7 Sacsayhuaman & Kenko – Have you always dreamed of Sacred Ceremony Picchu, the Sacred Valley, Day 8 Ollantaytambo – Sanctuary of the Ollantaytambo, spiritual places of going to Machu Picchu? Wind – Sacred Ceremony mystical Peru & much more! • World renowned Shaman and guide, Day 9 Lake Titicaca Go to our website at: Jorge Luis Delgado Day 10 Floating Islands of Uros & SedonaSoulAdventures.com/Peru-Tours Amantani Island (overnight with a • 3 days at Machu Picchu local family on Amantani) Sacred • 5 days in Cusco and the Sacred Valley Ceremony on Amantani Questions? Contact Us • 5 days at Lake Titicaca Day 11 Boat ride across Lake Titicaca • Overnight in Amantani, with local Toll-free US & Canada: (877) 204-3664 to Puno family Office number direct: (928) 204-5988 Day 12 Aramu Muru Interdimensional • Uros, the floating Islands Gateway - Sacred Ceremony • Aramu Muru...the interdimensional Email Debra: Day 13 Sillustani Temple gateway [email protected] - Sacred Ceremony • Ollantaytambo, power spot of Llama & Day 14 Fly to Lima and Home Puma Detailed Information on our website: • Urco, Pisac and Sillustani SedonaSoulAdventures.com/Peru-Tours • Sacsayhuaman & Kenko • Sacred ceremonies and meditations throughout the journey 100% Refundable • 100% refundable through April 1, 2021 through April 1, 2021 Join us for the trip of a lifetime! Jorge Luis Delgado is an internationally Imagine Yourself known teacher of Inca spirituality and a modern Inca chacaruna, a bridge person, In Sacred Ceremony at who assists people in connecting to their Machu Picchu on the Solstice spiritual self within their own traditions. -

BAPUCP6 10 De La Vega-Stanish

BOLETÍNLOS DE CENTROSARQUEOLOGÍA DE PEREGRINAJE PUCP, N.° 6,COMO 2002, MECANISMOS 265-275 DE INTEGRACIÓN POLÍTICA... 265 LOS CENTROS DE PEREGRINAJE COMO MECANISMOS DE INTEGRACIÓN POLÍTICA EN SOCIEDADES COMPLEJAS DEL ALTIPLANO DEL TITICACA Edmundo de la Vega* y Charles Stanish** Resumen Las peregrinaciones a lugares sagrados fueron una práctica común en diversas sociedades andinas prehispánicas. Las islas del Sol y de la Luna, en el lado sur del lago Titicaca, se interpolan en una de las más importantes rutas de peregrinación que impusieron los incas como parte de su política de dominio estatal. De igual modo, los centros funerarios de Cutimbo y Sillustani, pertenecientes a los señoríos Lupaqa y Colla respectivamente, convocaron peregrinaciones anuales en el marco de ceremonias de culto a los antepasados. Utilizando documentación etnohistórica e información arqueológica, referentes a tales centros de peregrinaje, se discute la hipótesis sobre el uso de las peregrinaciones como mecanismos ideológicos de control social y político por parte de sociedades complejas. Abstract CENTERS OF PILIGRIMAGE AS MECHANISMS OF POLITICAL INTEGRATION IN COMPLEX SOCIETIES IN TITICACA’S ALTIPLANO Pilgrimages to sacred places were a common practice in many prehispanic Andean societies. For example, the islands of the Sun and the Moon, located in southern Lake Titicaca, formed one of the most important pilgrimage routes imposed by the Inca state as part of its politics of state domain. Similarly, the mortuary centers of Cutimbo and Sillustani, belonging respectively to the Lupaqa and Colla chiefdoms, re- ceived annual pilgrimages as part of cult ceremonies dedicated to the ancestors. Using ethnohistorical documentation and archaeological information with regard to such pilgrimage centers, we discuss the hypothesis that the pilgrimages served as ideological mechanisms of social and politi- cal control on the part of complex societies.