It Was Sheer Genius for the UK Firm Core Design to Create a Sleek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider Jingjing Liu University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-10-2018 Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider Jingjing Liu University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Liu, Jingjing, "Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7542 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider by Jingjing Liu A thesis submitted in part fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Zimmerman School of Advertising and Mass Communications College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kelli Burns, Ph.D. Scott S. Liu, Ph.D. Roxanne Watson, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 17, 2018 Keywords: gender stereotypes, sexualization, games, Lara Copyright © 2018, Jingjing Liu DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents. Thanks for always encouraging and supporting me. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 24.04.2018 K.Flay Mit Ihrem Album „Every Where Is Some Where“ Auf Tour

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 24.04.2018 K.Flay mit ihrem Album „Every Where Is Some Where“ auf Tour Toughe Heldinnen brauchen einen toughen Soundtrack. Und wenn Lara Croft sich dieser Tage im dritten Teil der „Tomb Raider“-Serie durch alle Gefahren kämpft, denen sich eine furchtlose Archäologin eben auf der Suche nach ihrem Vater gegenübersieht, passt es exzellent, dass K.Flay auf dem zugehörigen Album vertreten ist. „Run For Your Life“ ist eine elektronisch verfremdete, gehetzte, gezischte, geraunte akustische Version der obercoolen Film-Heroine. Nach dem Feature auf Robert DeLongs jüngster Single „Favorite Color Is Blue“ (die nebenbei gesagt längst die Millionengrenze bei Spotify geknackt hat) hat die Musikerin also ein zweites neues Stück veröffentlicht, dass die Wertschätzung widerspiegelt, die der Amerikanerin inzwischen entgegen gebracht wird. Zurzeit ist sie mit Imagine Dragons auf Europa-Tour und hat eben erst mit ihrer kleinen Band bei drei exklusiven Headline-Shows unsere Häuser gerockt. Jetzt hat K.Flay bestätigt, dass sie im Oktober für fünf weitere Auftritte nach Deutschland kommt. Mit ihrem Genre-Mashup aus Indie, Pop, Electro, R’n’B und Rap verzichtet die aus Illinois stammende Sängerin und Gitarristin auf Grenzen jeglichen Mainstreams. Ihre jüngste Platte „Every Where Is Some Where“ klingt trotzig und bewusst grobkörnig, dabei extrem verdichtet und gewissermaßen ungeschminkt. Deshalb spielen auch Live-Gitarren, Bass-Parts und Schlagzeugaufnahmen so eine zentrale Rolle auf diesem neuen Album und bei der überzeugenden Live-Performance. Die Lyrics haben durchaus literarische Qualitäten, was nicht so sehr verwundert, wenn man bedenkt, dass K.Flay unter anderem die Autorin Marilynne Robinson zu ihren Inspirationsquellen zählt. -

Interview Responses from Queer Tomb Raider Fans

Interview responses from queer Tomb Raider fans Template response form sent to consenting parties: Your name or chosen alias (Anonymous is fine too): Country: Age: How you identify: --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? 3) Can you describe Lara Croft's impact on your sexuality? (If not and/or you don't feel she's been an influence, that's fine too). 4) Do you have a Lara preference - Classic or Reboot? Name: Joshua B. Country: USA Age: 22 How you identify: Cisgender gay man --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) I've only been a fan for about a year! I got into the series in 2014 with Tomb Raider (2013). I later branched out and explored the classic series by Core Design and disliked them, but I was only really inspired/convinced to return to the Core games when my ex-boyfriend brought up a new viewpoint: people play Tomb Raider for puzzles, not for plot. And so I went back and I was hooked! A year later, here I am as a Tomb Raider fanatic. 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? I really admired how 2013 Lara grew into this hardened “cool”-type character while still remaining grounded. I was drawn to her and I still think she’s a lovely woman, but classic Lara is my favourite. -

Can't Go Home by Noelle Adams / Pfangirl PART 1

Can't go home By Noelle Adams / pfangirl PART 1 - SUFFOCATED A caged lioness. That's what Lara reminded Sam of now. Every time she looked at her best friend, the American thought of the big cat she'd seen in a German zoo during her globe- trotting childhood. It wouldn't lie still. It was pure feral energy, striding back and forth in its enclosure, muscles rippling beneath its pelt. Lara was the same. Lithe grace and power in human form, always moving, always intensely focused on some task or thing. Almost permanently scowling. Sam had always wondered which of her parents Lara inherited her effortless physicality from. Four years of knowing Lara, and Sam still wasn't sure. There were no photos for her to consult. The young archaeologist hardly spoke about her vanished mother and father. She avoided talking about them; evidently running from their memory like she ran from what had happened on Yamatai. In the one and a half months since the shipwreck – well, at least since she was released from hospital – Lara had been seized by a frantic, feverish vigour. They had travelled from Osaka to the UK, where Lara had spent a single day at her family's estate, ransacking her father's study. From there they headed to New York. This put Lara closer to her next intended stop – Roanoke Island. Although the city was a good base for Lara to work from while she planned her next expedition, there was a second, more distasteful reason for the archaeologist to be there: an exclusive television interview. -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

A Message from the Final Fantasy Vii Remake

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A MESSAGE FROM THE FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE DEVELOPMENT TEAM LONDON (14th January 2020) – Square Enix Ltd., announced today that the global release date for FINAL FANTASY® VII REMAKE will be 10 April 2020. Below is a message from the development team: “We know that so many of you are looking forward to the release of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE and have been waiting patiently to experience what we have been working on. In order to ensure we deliver a game that is in-line with our vision, and the quality that our fans who have been waiting for deserve, we have decided to move the release date to 10th April 2020. We are making this tough decision in order to give ourselves a few extra weeks to apply final polish to the game and to deliver you with the best possible experience. I, on behalf of the whole team, want to apologize to everyone, as I know this means waiting for the game just a little bit longer. Thank you for your patience and continued support. - Yoshinori Kitase, Producer of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE” FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE will be available for the PlayStation®4 system from 10th April 2020. For more information, visit: www.ffvii-remake.com Related Links: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/finalfantasyvii Twitter: https://twitter.com/finalfantasyvii Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/finalfantasyvii/ YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/finalfantasy #FinalFantasy #FF7R About Square Enix Ltd. Square Enix Ltd. develops, publishes, distributes and licenses SQUARE ENIX®, EIDOS® and TAITO® branded entertainment content in Europe and other PAL territories as part of the Square Enix group of companies. -

Polygons and Practice in Skies of Arcadia

Issue 02 – 2013 Journal –Peer Reviewed ZOYA STREET Gamesbrief [email protected] Polygons and practice in Skies of Arcadia This paper features research carried out at the Victoria and Albert Museum into the design history of Sega’s 2000 Dreamcast title, Skies of Arcadia (released in Ja- pan as Eternal Arcadia). It was released by Overworks, a subsidiary of Sega, at an interesting point in Japanese computer game history. A new generation of video game consoles was in its infancy, and much speculation in the industry sur- rounded how networked gaming and large, open, tridimensional game worlds would change game design in the years ahead. Skies of Arcadia is a game about sky pirates, set in a world where islands and continents foat in the sky. I became interested in this game because it was praised in critical reviews for the real sense of place in its visual design. It is a Jap- anese Role Playing Game (JRPG), meaning that gameplay focuses on exploring a series of spaces and defeating enemies in turn-based, probabilistic battles using a system similar to that established by tabletop games such as Dungeons & Dragons. This research is based on interviews with the producer Shuntaro Tanaka and lead designer Toshiyuki Mukaiyama, user reviews submitted online over the past 10 plus years, and historically informed design analysis. It is grounded in a broader study of the networks of production and consumption that surrounded and co-produced the Dreamcast as a cultural phenomenon, technological agent and played experience. Through design analysis, oral history and archival research, in this paper I will complicate notions of tridimensionality by placing a three dimensional RPG in a broader network of sociotechnical relationships. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Tomb Raider III (PC)

END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT AND LIMITED WARRANTY Tomb Raider III (PC) IMPORTANT - Please read this End User Licence Agreement (“EULA”) carefully before installing this Software Product. By installing, copying, and/or otherwise using the Software Product you agree to be bound by the terms of this EULA and we are only prepared to licence you to use the Software Product on the terms of this EULA. Before installing this Software Product please make sure that your computer meets the minimum technical specifications for the proper operation of this Software Product. YOUR PARTICULAR ATTENTION IS DRAWN TO: - THE EXCLUSION CLAUSE AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY CONTAINED IN PARAGRAPH 9 BELOW; AND - THE PROVISIONS OF PARAGRAPHS 4 AND 5 WHICH DESCRIBE CERTAIN INFORMATION WHICH MAY BE COLLECTED, STORED AND USED BY US AS A RESULT OF YOUR INSTALLATION AND USE OF THIS SOFTWARE PRODUCT AND/OR ONLINE FEATURES AND EXPLAINS HOW YOUR PERSONAL DATA WILL BE PROTECTED. BY ACCEPTING THIS EULA AND INSTALLING THIS SOFTWARE PRODUCT YOU ARE GIVING YOUR CONSENT TO OUR COLLECTION, STORAGE, USE AND PROCESSING OF SUCH INFORMATION AND DATA IN ACCORDANCE WITH PARAGRAPH 5, OUR PRIVACY AND COOKIES POLICIES. SEL TAKES YOUR PRIVACY SERIOUSLY AND WE STRONGLY RECOMMEND YOU TAKE TIME TO READ OUR PRIVACY POLICY AND COOKIES POLICY AND PERIODICALLY CHECK FOR ANY UPDATES MADE TO IT. (i) PURCHASE OF SOFTWARE PRODUCT BY DOWNLOAD IF YOU AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THIS EULA PLEASE CLICK "I ACCEPT" AT THE END OF THIS EULA AT WHICH POINT THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT WILL BE INSTALLED ONTO YOUR HARD DRIVE. IF YOU DO NOT AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THE TERMS OF THIS EULA CLICK "NOT ACCEPTED" AND THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT WILL NOT BE LOADED ONTO YOUR HARD DRIVE AND NO LICENCE SHALL BE GRANTED TO YOU IN RESPECT OF THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT. -

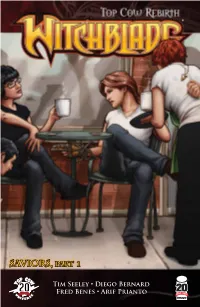

Saviors, PART 1

® Saviors, PART 1 Tim Seeley • Diego Bernard 201992 - 2012 Fred Benes • Arif Prianto Previously In Tim Seeley • writer Diego Bernard • penciller Cover A • John Tyler Christopher Fred Benes • inker Cover B • Diego Bernard, Fred Benes, SAVIORS, Pt. 1 Arif Prianto • colorists & Arif Prianto Troy Peteri • letterer Bryan Rountree, Matt Hawkins, & Filip Sablik • editors Witchblade created by Marc Silvestri, David Wohl, Brian Haberlin, & Michael Turner WITCHBLADE® ISSUE 158. JULY 2012. FIRST PRINTING Published by Image Comics Inc. Office of Publication: 2134 Allston Way, Second Floor, Berkeley, CA For Top Cow Productions, Inc. 94704. $2.99 US. WITCHBLADE® 2012 Top Cow Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. “Witchblade,” the Witchblade logos, and the likenesses of all featured Marc Silvestri - CEO characters (human or otherwise) featured herein are registered trademarks of Top Cow Productions, Inc. Image Comics and the Image Comics logo are Matt Hawkins - President and COO trademarks of Image Comics Inc. The characters, events, and stories in this Bryan Rountree – Managing Editor publication are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or Elena Salcedo – Director of Operations dead), events, institutions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. No Betsy Gonia - Production Assistant portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the express written permission of Top Cow Productions, Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. For information regarding the CPSIA on this printed material call: 203-595-3636 and provide reference # RICH – 448584. “The challenge is Trying To capTure imaginaTion wiTh lines. BuT when iT works, comics can Be amazing.” Jason howarD ExpEriEncE crEativity Image Comics® and its logos are registered trademarks of Image Comics, Inc. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans.