Event Transcript: Design Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider Jingjing Liu University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-10-2018 Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider Jingjing Liu University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Liu, Jingjing, "Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7542 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender Sexualization in Digital Games: Exploring Female Character Changes in Tomb Raider by Jingjing Liu A thesis submitted in part fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Zimmerman School of Advertising and Mass Communications College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kelli Burns, Ph.D. Scott S. Liu, Ph.D. Roxanne Watson, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 17, 2018 Keywords: gender stereotypes, sexualization, games, Lara Copyright © 2018, Jingjing Liu DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents. Thanks for always encouraging and supporting me. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... -

Can't Go Home by Noelle Adams / Pfangirl PART 1

Can't go home By Noelle Adams / pfangirl PART 1 - SUFFOCATED A caged lioness. That's what Lara reminded Sam of now. Every time she looked at her best friend, the American thought of the big cat she'd seen in a German zoo during her globe- trotting childhood. It wouldn't lie still. It was pure feral energy, striding back and forth in its enclosure, muscles rippling beneath its pelt. Lara was the same. Lithe grace and power in human form, always moving, always intensely focused on some task or thing. Almost permanently scowling. Sam had always wondered which of her parents Lara inherited her effortless physicality from. Four years of knowing Lara, and Sam still wasn't sure. There were no photos for her to consult. The young archaeologist hardly spoke about her vanished mother and father. She avoided talking about them; evidently running from their memory like she ran from what had happened on Yamatai. In the one and a half months since the shipwreck – well, at least since she was released from hospital – Lara had been seized by a frantic, feverish vigour. They had travelled from Osaka to the UK, where Lara had spent a single day at her family's estate, ransacking her father's study. From there they headed to New York. This put Lara closer to her next intended stop – Roanoke Island. Although the city was a good base for Lara to work from while she planned her next expedition, there was a second, more distasteful reason for the archaeologist to be there: an exclusive television interview. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

1 Selectmen's Meeting MINUTES

Selectmen’s Meeting MINUTES - AMENDED ON May 20th, 2021 Bristol Town Office, April 21st, 2021 Selectmen Present: Chad Hanna, Kristine Poland, Paul Yates Also Present: Chris Hall (Town Administrator); Jessica Westhaver (Treasurer); Rachel Bizarro (Clerk); Laurie Mahan and Sandra Lane (Parks Commissioners); Lara Decker (Parks Director); John Stolecki, Robert Ball and Rick Poland Jr. (Harbor Committee); Paul Leeman, Jr. (Fire Chief); Scott Sutter (Fire Chief-nominee); Steve Lackovic (Shellfish Committee); Natasha Salvo; William Gerstmeyer; David Morse. The Board was called to order by Chair Hanna at 7.00 pm. Report on Executive Session: Chair Hanna reported that the Board had met in Executive Session on Wednesday, April 14th, at 7 pm, to discuss personnel matters pursuant to M.R.S. Title 1, chapter 13, section 405.6.A. Hanna reported that in Executive Session the Board had agreed: - To employment contract terms for the new Fire Chief; - To defer a meeting of all departments’ staff, previously discussed, until the completion of the ongoing compensation review; - To bring the policy on use of municipal vehicles to this day’s meeting for public discussion; - To hold a further Executive Session, with the Town Administrator, on additional personnel matters. It was moved by Yates, seconded by Poland, to approve the Minutes of the meeting of March 31st. Motion passed, 3 - 0. Bid Opening: Two bids were received for the replacement of the damaged metal roof on the Hanna Landing Storage Building, with a 24 gauge standing seam steel roof as follows: - Williams Construction Company, $27,630; - Maine Highlands Contracting, $67,657. After verifying that both bids were for similar scopes of work and materials, and that both had supplied proof of insurance, it was moved by Yates, seconded by Poland, to accept the bid from Williams Construction Company in the amount of $27,630.00. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Read Book Justice League Movie 2017 Coloring Book Cast

JUSTICE LEAGUE MOVIE 2017 COLORING BOOK CAST & CHARACTERS EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mega Media Depot | 92 pages | 29 Mar 2017 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781545022221 | English | none Justice League Movie 2017 Coloring Book Cast & Characters Edition PDF Book Witness 1 uncredited Dolly Jagdeo Sign Up. Even comic book neophytes can clue in on the distinct differences between those names, and while the two planets were once one, they are now two very different habitats. Office Assistant uncredited Joanne Batten Fueled by his restored faith in humanity and inspired by Superman 's selfless act, Bruce Wayne enlists the help of his newfound ally, Diana Prince , to face an even greater enemy. Who TV Series Lovers will actually use and enjoy for years to come, then Hamada had no involvement, since filming occurred before Mr. Officer Ben Sadowsky. In September, as Fisher's allegations continued, Warner Bros. Welsh Tavern Barkeep Gianpiero Cognoli Fisher that he would elevate his concerns to WarnerMedia so they could conduct an investigation. Superman is still confused and he attacks the group after Cyborg accidentally launches a projectile at him. Passerby uncredited. School Faculty uncredited. Paris Kyren Parker Task Force Deputy uncredited Matt Symonds Bennett uncredited. Chris Terrio School Girl's Friend Mia Burgess School Teacher. Justice League Movie 2017 Coloring Book Cast & Characters Edition Writer Fisher insisted that WarnerMedia hire an independent third party investigator. Superman : Yes, it does. All rights reserved. Man in Waiting Room uncredited. Advertisement - Continue Reading Below. Epione uncredited Kenny-Lee Mbanefo School Girl's Friend Constance Bole In his sequel Batman v. -

2018-19 INSIDER Staff: Dayanna Perez, David Fender, Christian

Volume 7, Issue 1 October 2018 11880 Roswell Ave. Chino, CA I will survive!!! 2018-19 INSIDER Staff: Dayanna Perez, David Inside this issue: Fender, Christian Hartson, Toxic People/Trends 2-3 Duke Hernandez, Emma Trujillo, Reese Gonzales, Fortnite vs. H1Z1/Comic 4-5 Kelea Alicea Lara, Breann D.C. Comics vs. Marvel 6-7 Hill, Angel Cesma, Gavin Watch & Listen 8 Hrynezuk, Jackie Guerrero, Horoscopes 9 Annalisa Contreraz, Julia Zelaya, Alyah Tolentino Bullies/Masks/Urban Legends 10-11 T h e B r i g g s Scary Story 12 Page 2 Toxic People INSIDER Toxic People Cleanse By Emma Trujillo then you go ahead and have fun! Put yourself out there and meet new and better people Join school clubs they wouldn’t join. You can partner up with the new kid or ask someone you think would be nice to hangout. Do different sports and activities. Don’t list every single reason why they’re bad for you Again, this is only wasting your time. Plus, you don’t want to make them feel bad, or even worse it’ll aggra- vate them and they definitely won’t leave you alone. Don’t stoop to their level and focus on “revenge” Have a mindset that it will take time or “getting back at them.” Getting rid of a bad person in your life isn’t always Not only are you starting to act like this person but it’s easy. You can’t just say, “You’re not going to be in my completely stupid. I mean come on, just forgive and life anymore.” That’ll only make them want to bug you forget. -

Superhero Origins As a Sentence Punctuation Exercise

Superhero Origins as a Sentence Punctuation Exercise The Definition of a Comic Book Superhero A comic book super hero is a costumed fictional character having superhuman/extraordinary skills and has great concern for right over wrong. He or she lives in the present and acts to benefit all mankind over the forces of evil. Some examples of comic book superheroes include: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, and Plastic Man. Each has a characteristic costume which distinguishes them from everyday citizens. Likewise, all consistently exercise superhuman abilities for the safety and protection of society against the forces of evil. They ply their gifts in the present-contemporary environment in which they exist. The Sentence Punctuation Assignment From earliest childhood to old age, the comics have influenced reading. Whether the Sunday comic strips or editions of Disney’s works, comic book art and narratives have been a reading catalyst. Indeed, they have played a huge role in entertaining people of all ages. However, their vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall appropriateness as a reading resource is often in doubt. Though at times too “graphic” for youth or too “childish” for adults, their use as an educational resource has merit. Such is the case with the following exercise. Superheroes as a sentence punctuation learning toll. Among the most popular of comic book heroes is Superman. His origin and super-human feats have thrilled comic book readers, theater goers, and television watchers for decades. However, many other comic book superheroes exist. Select one from those superhero origin accounts which follow and compose a four paragraph superhero origin one page double-spaced narative of your selection. -

It Was Sheer Genius for the UK Firm Core Design to Create a Sleek

Gender and Videogames: the political valency of Lara Croft Maja Mikula, University of Technology Sydney The Face: Is Lara a feminist icon or a sexist fantasy? Toby Gard: Neither and a bit of both. Lara was designed to be a tough, self-reliant, intelligent woman. She confounds all the sexist cliches apart from the fact that she’s got an unbelievable figure. Strong, independent women are the perfect fantasy girls – the untouchable is always the most desirable. (Interview with Lara’s creator Toby Gard in The Face magazine, June 1997) Lara Croft is a fictional character: a widely popular videogame1 superwoman and recently also the protagonist of the blockbuster film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001). Her body is excessively feminine - her breasts are massive and very pert, her waist is tiny, her hips are rounded and she wears extremely tight clothing. She is also physically strong, can fight and shoot, has incredible gymnastic abilities and is a best selling writer. Germaine Greer does not like Lara Croft. In her latest book, The Whole Woman (1999), Greer has unequivocally condemned the enforcement of artificial and oppressive ideals of femininity through pop icons such as the Barbie Doll. Lara Croft, whose ‘femaleness’ is clearly shaped by a desire to embody male sexual fantasies, is the antithesis of Greer’s ‘whole woman’; Greer calls her a: ‘sergeant-major with balloons stuffed up his shirt […] She’s a distorted, sexually ambiguous, male fantasy. Whatever these characters are, they’re not real women’ (Jones, 2001). 1 She may not be a 'real woman', but on the other hand Lara is clearly a 'positive image' for women, as Linda Artel and Susan Wengraf defined the term in 1976: The primary aim of [annotated guide] Positive Images was to evaluate media materials from a feminist perspective. -

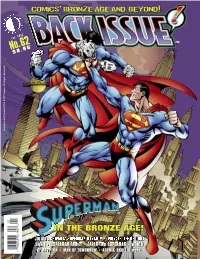

IN the BRONZE AGE! BRONZE the in , Bronze AGE and Beyond and AGE Bronze I

Superman and Bizarro TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 1 No.62 Feb. 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs JULIUS SCHWARTZ SUPERMAN DYNASTY • PRIVATE LIFE OF CURT SWAN • SUPERMAN FAMILY • EARTH-TWO SUPERMAN • WORLD OF KRYPTON • MAN OF TOMORROW • ATOMIC SKULL & more! IN THE BRONZE AGE! , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 62 February 2013 Celebrating the Best ® Comics of the '70s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '80s,'90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael “Don’t Call Me Chief!” Eury PUBLISHER John “Morgan Edge” Morrow DESIGNER Rich “Superman’s Pal” Fowlks COVER ARTISTS José Luis García-López and Scott Williams COVER COLORIST Glenn “Grew Up in Smallville” Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael “Last Son of Krypton” Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 A dedication to the man who made us believe he could fly, Christopher Reeve PROOFREADER Rob “Cub Reporter” Smentek FLASHBACK: The Julius Schwartz Superman Dynasty . .3 SPECIAL THANKS Looking back at the Super-editor(s) of the Bronze Age, with enough art to fill a Fortress! Murphy Anderson Dennis O’Neil SUPER SALUTE TO CARY BATES . .18 CapedWonder.com Luigi Novi/Wikimedia Cary Bates Commons SUPER SALUTE TO ELLIOT S! MAGGIN . .20 Kurt Busiek Jerry Ordway Tim Callahan Mike Page BACKSTAGE PASS: The Private Life of Curt Swan . .23 Howard Chaykin Mike Pigott Fans, friends, and family revisit the life and career of THE Superman artist Gerry Conway Al Plastino DC Comics Alex Ross FLASHBACK: Superman Calls for Back-up! . .38 Dial B for Blog Bob Rozakis The Man of Steel’s adventures in short stories Tom DeFalco Joe Rubinstein FLASHBACK: Superman Family Portraits . -

The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 10 Issue 2 October 2006 Article 6 October 2006 The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2006) "The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol10/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman Abstract Superman, the original superhero, is a culmination of the great mythic heroes of the past. The hero's journey, a recurring cycle of events in mythology, is described by Joseph Campbell. The three acts in Superman: The Movie portray a complex calling to the superhero's role, consisting of three distinct calls and journeys. Each of the three stages includes the death of someone close to him, different symbols of his own death and resurrection, and different experiences of atonement with a father figure. Analyzing these mythic cycles bestows the viewer with a heroic "elixir.” This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol10/iss2/6 Stucky: The Superhero's Mythic Journey Introduction Since 1938, Superman has been popular culture's paradigmatic hero, and the original superhero has lived in many forms of media, from comic books to television series to film versions that include the 2006 Superman Returns.1 His story is a culmination of the great mythic heroes of the past. -

MAXIMUM GAGA with a CRITICAL INTRODUCTION on GURLESQUE POETICS by LARA GLENUM (Under the Direction of Jed Rasula) ABSTRACT the G

MAXIMUM GAGA WITH A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION ON GURLESQUE POETICS by LARA GLENUM (Under the direction of Jed Rasula) ABSTRACT The Gurlesque describes an emerging field of female poets and who, taking a page form the burlesque, perform their femininity in a campy or overtly mocking way. Their work assaults the norms of acceptable female behavior by irreverently deploying gender stereotypes to subversive ends. The critical portion of this dissertation outlines several theoretical tangents germane to Gurlesque poetics:, namely burlesque and camp, “girly kitsch,” and the female grotesque; the poetry manuscript that follows, Maximum Gaga, is a prime example of the latter. INDEX WORDS: Poetry, poetics, creative writing, Gurlesque, avant-garde, burlesque, camp, kitsch, grotesque MAXIMUM GAGA WITH A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION ON GURLESQUE POETICS by LARA GLENUM B.A. The University of Georgia, 1994 M.F.A. The University of Virginia, 2000 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GA 2009 ©2009 LARA GLENUM All Rights Reserved MAXIMUM GAGA WITH A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION ON GURLESQUE POETICS by LARA GLENUM Major Professor: Jed Rasula Committee: Susan Rosenbaum Ed Pavlic Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Joyelle McSweeney and Johannes Goransson, my editors at Action Books, for shepherding Maximum Gaga into publication. Thanks to Arielle Greenberg and Danielle Pafunda for our sustained dialogue on Gurlesque poetics; thanks, too, to Henri Israeli of Saturnalia Books for taking on publication of the Gurlesque anthology.