CUMENT FILMED Imord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping News -- 1 --Media Power

Shaping News – 1 Theories of Media Power and Environment Course Description: The focus in these six lectures is on how some facts are selected, shaped, and by whom, for daily internet, television, and print media global, national, regional, and local dissemination to world audiences. Agenda-setting, priming, framing, propaganda and persuasion are major tools to supplement basic news factors in various media environments. Course Goals and Student Learning Objectives: The overall goal is to increase student awareness that media filter reality rather than reflect it, and those selected bits of reality are shaped to be understood. Student learning objectives are: 1. Demonstrate how media environments and media structures determine what information is selected for dissemination; 2. Demonstrate how and why different media disseminate different information on the same situation or event; 3. Demonstrate how information is framed, and by whom, to access the media agenda. Required Texts/Readings: Read random essays and research online that focus on media news factors, agenda-setting and framing Assignments and Grading Policy: Two quizzes on course content plus a 20-page paper on a related, student- selected and faculty-approved research paper. Shaping News – 1 Media Environments and Media Power This is the first of six lectures on the shaping on news. It will focus on the theories of media environments based on the assumption that media are chameleon and reflect the governmental/societal system in which they exist. The remaining five lectures are on: (2) elements of news; (3) agenda-setting and framing; (4) propaganda; (5) attitude formation; and (6) cognitive dissonance. Two philosophical assumptions underlying the scholarly examination of mass media are that (1) the media are chameleons, reflecting their environment, and (2) their power is filtered and uneven. -

Sacred Sci-Fi Orson Scott Card As Mormon Mythmaker

52-59_smith_card:a_chandler_kafka 2/13/2011 8:57 pm page 52 SUNSTONE I, Ender, being born of goodly parents . SACRED SCI-FI ORSON SCOTT CARD AS MORMON MYTHMAKER By Christopher C. Smith LMOST EVERY CULTURE HAS TRADITIONAL new myths are less vulnerable than the old mythologies be - mythologie s— usually stories set in a primordial cause they make no claim to be literally, historically true. A time of gods and heroes. Although in popular dis - Their claim to truth is at a deeper, more visceral level. course the term “myth” typically refers only to fiction, lit - Fantasy and science fiction can be used either to chal - erary critics and theologians use it to refer to any “existen - lenge and replace or to support and complement traditional tial” stor y— even a historical one. Myths explain how the religious mythologies. One author who has adopted the world came to be, why it is the way it is, and toward what latter strategy is Mormon novelist Orson Scott Card. end it is headed. They explore the meaning of life and pro - Literary critic Marek Oziewicz has found in Card’s fiction all vide role models for people to imitate. They express deep the earmarks of a modern mythology. It has universal scope, psychological archetypes and instill a sense of wonder. In creates continuity between past, present, and future, inte - short, they answer the Big Questions of life and teach us grates emotion and morality with technology, and posits the how to live. interrelatedness of all existence. 2 Indeed, few science fiction Due to modernization in recent centuries, the world has and fantasy authors’ narratives feel as mythic as Card’s. -

The Lost Boys of Bird Island

Tafelberg To the lost boys of Bird Island – and to all voiceless children who have suffered abuse by those with power over them Foreword by Marianne Thamm Secrets, lies and cover-ups In January 2015, an investigative team consisting of South African and Belgian police swooped on the home of a 37-year-old computer engineer, William Beale, located in the popular Garden Route seaside town of Plettenberg Bay. The raid on Beale came after months of meticulous planning that was part of an intercontinental investigation into an online child sex and pornography ring. The investigation was code-named Operation Cloud 9. Beale was the first South African to be arrested. He was snagged as a direct result of the October 2014 arrest by members of the Antwerp Child Sexual Exploitation Team of a Belgian paedophile implicated in the ring. South African police, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Heila Niemand, cooperated with Belgian counterparts to expose the sinister network, which extended across South Africa and the globe. By July 2017, at least 40 suspects had been arrested, including a 64-year-old Johannesburg legal consultant and a twenty-year-old Johannesburg student. What police found on Beale’s computer was horrifying. There were thousands of images and videos of children, and even babies, being abused, tortured, raped and murdered. In November 2017, Beale pleaded guilty to around 19 000 counts of possession of child pornography and was sentenced to fifteen years in jail, the harshest punishment ever handed down in a South African court for the possession of child pornography. -

APA Newsletters NEWSLETTER on HISPANIC/LATINO ISSUES in PHILOSOPHY

APA Newsletters NEWSLETTER ON HISPANIC/LATINO ISSUES IN PHILOSOPHY Volume 09, Number 1 Fall 2009 FROM THE EDITOR, BERNARDO J. CANTEÑS ARTICLES EDUARDO MENDIETA “The Unfinished Constitution: The Education of the Supreme Court” JORGE J. E. GRACIA “Sotomayor on the Interpretation of the Law: Why She is Right for the Supreme Court” SUZANNE OBOLER “The Ironies of History: Puerto Rico’s Status and the Nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor” ANGELO CORLETT “A Wise Latina” LINDA MARTÍN ALCOFF “Sotomayor’s Reasoning” MINERVA AHUMADA TORRES “Aztec Metaphysics: Poetry in Orphanhood” ALEJANDRO SANTANA “The Aztec Conception of Time” CAROL J. MOELLER “Minoritized Thought: Open Questions of Latino/a and Latin-American Philosophies” BOOK REVIEW Edwina Barvosa, Wealth of Selves: Multiple Identities, Mestiza Consciousness, and the Subject of Politics REVIEWED BY AGNES CURRY SUBMISSIONS CONTRIBUTORS © 2009 by The American Philosophical Association APA NEWSLETTER ON Hispanic/Latino Issues in Philosophy Bernardo J. Canteñs, Editor Fall 2009 Volume 09, Number 1 Angelo Corlett’s “A Wise Latina” takes on this criticism by first ROM THE DITOR placing the statement within the context of the larger text, and F E then going on to argue for the common sense and innocuous nature of the claim once it is properly interpreted and correctly understood. Finally, Sotomayor’s nomination raises the This edition of the Newsletter includes a series of essays on question of social identity and rationality, and their complex the nomination of Sonia María Sotomayor to the U.S. Supreme epistemological relationship. Linda Alcoff argues cogently Court. Sotomayor was nominated by President Barack Obama that our experiences and social identity are an important and to the Supreme Court on May 26, 2009, to replace Justice David relevant part of how we “judge relevance, coherence, and Scouter. -

Propaganda and Marketing: a Review Dr

© 2019 JETIR July 2019, Volume 6, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Propaganda and Marketing: A review Dr. Smita Harwani Sr. Assistant Professor Department of management studies New Horizon College of Engineering. ABSTRACT Propaganda is a concerted set of messages aimed at influencing the opinions or behavior of large number of people. It has been observed that Propaganda and advertising sometimes go hand in hand. This paper focuses on analyzing Propaganda in advertising with special emphasis on Adolf Hitler’s propaganda techniques. To create history, knowing history is awfully important. Hitler was well known for his dictatorship apart from that he was exceptional at influencing people, influence is what happens more in modern day marketing, isn’t it? Hitler influenced people through technical devices like radio and the loud speaker and around eighty million people were deprived of independent thought in those days due to his propaganda techniques. It can only be imagined what he would have done at present if he had access to all modern means of communication. Since Hitler’s work has been carried out in those fields of applied psychology and neurology which are the special province of the propagandist the indoctrinator and brain washer. Today the art of mind control is in process of becoming a science. To be a leader means to be able to move the masses and this is what today’s advertisement methods aim to do. Hitler’s aim was first to move masses and then, having pried them loose from their traditional thoughts and behavior. To be successful a propagandist must learn how to manipulate these instincts and emotions. -

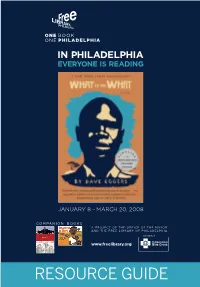

Reading and Resource Guide

IN PHILADELPHIA EVERYONE IS READING JANUARY 8 – MARCH 20, 2008 COMPANION BOOKS A PROJECT OF THE OFFICE OF THE MAYOR AND THE FREE LIBRARY OF PHILADELPHIA Lead Sponsor: www.freelibrary.org RESOURCE GUIDE One Book, One Philadelphia is a joint project of the Mayor’s Office and the Free Library of Philadelphia. The mission of the program—now entering its sixth year—is to promote reading, literacy, library usage, and community building throughout the Greater Philadelphia region. This year, the One Book, One Philadelphia Selection Committee has chosen Dave Eggers’ What Is the What as the featured title of the 2008 One Book program. To engage the widest possible audience while encouraging intergenerational reading, two thematically related companion books were also selected for families, children, and teens—Mawi Asgedom’s Of Beetles and Angels: A Boy’s Remarkable Journey from a Refugee Camp to Harvard and Mary Williams’ Brothers In Hope: The Story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Both of these books provide children and adults opportunities to further understand and discuss the history of the conflict in Sudan, as well as other issues of violence in the world and in our own region. Contents Read one, or read them all—just be sure to get 2 Companion Titles out there and share your opinions! 3 Questions for Discussion What Is the What For more information on the 2008 One Book, Of Beetles and Angels: One Philadelphia program, please visit our A Boy’s Remarkable Journey from a Refugee Camp to Harvard website at www.freelibrary.org, where you Brothers In Hope: The Story can view our calendar of events, download of the Lost Boys of Sudan podcasts of One Book author appearances, 6 Timeline: A Recent History of Sudan and post comments on our One Book Blog. -

I Correlative-Based Fallacies

Fallacies In Argument 本文内容均摘自 Wikipedia,由 ode@bdwm 编辑整理,请不要用于商业用途。 为方便阅读,删去了原文的 references,见谅 I Correlative-based fallacies False dilemma The informal fallacy of false dilemma (also called false dichotomy, the either-or fallacy, or bifurcation) involves a situation in which only two alternatives are considered, when in fact there are other options. Closely related are failing to consider a range of options and the tendency to think in extremes, called black-and-white thinking. Strictly speaking, the prefix "di" in "dilemma" means "two". When a list of more than two choices is offered, but there are other choices not mentioned, then the fallacy is called the fallacy of false choice. When a person really does have only two choices, as in the classic short story The Lady or the Tiger, then they are often said to be "on the horns of a dilemma". False dilemma can arise intentionally, when fallacy is used in an attempt to force a choice ("If you are not with us, you are against us.") But the fallacy can arise simply by accidental omission—possibly through a form of wishful thinking or ignorance—rather than by deliberate deception. When two alternatives are presented, they are often, though not always, two extreme points on some spectrum of possibilities. This can lend credence to the larger argument by giving the impression that the options are mutually exclusive, even though they need not be. Furthermore, the options are typically presented as being collectively exhaustive, in which case the fallacy can be overcome, or at least weakened, by considering other possibilities, or perhaps by considering a whole spectrum of possibilities, as in fuzzy logic. -

Build a Be4er Neplix, Win a Million Dollars?

Build a Be)er Ne,lix, Win a Million Dollars? Lester Mackey 2012 USA Science and Engineering FesDval Nelix • Rents & streams movies and TV shows • 100,000 movie Dtles • 26 million customers Recommends “Movies You’ll ♥” Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Hated it! Loved it! Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ How This Works Top Secret Now I’m Cinematch Computer Program I don’t unhappy! like this movie. Your Predicted Rang: Back at Ne,lix How can we Let’s have a improve contest! Cinematch? What should the prize be? How about $1 million? The Ne,lix Prize October 2, 2006 • Contest open to the world • 100 million movie rangs released to public • Goal: Create computer program to predict rangs • $1 Million Grand Prize for beang Cinematch accuracy by 10% • $50,000 Progress Prize for the team with the best predicDons each year 5,100 teams from 186 countries entered Dinosaur Planet David Weiss David Lin Lester Mackey Team Dinosaur Planet The Rangs • Training Set – What computer programs use to learn customer preferences – Each entry: July 5, 1999 – 100,500,000 rangs in total – 480,000 customers and 18,000 movies The Rangs: A Closer Look Highest Rated Movies The Shawshank RedempDon Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King Raiders of the Lost Ark Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers Finding Nemo The Green Mile Most Divisive Movies Fahrenheit 9/11 Napoleon Dynamite Pearl Harbor Miss Congeniality Lost in Translaon The Royal Tenenbaums How the Contest Worked • Quiz Set & Test Set – Used to evaluate accuracy of computer programs – Each entry: Rang Sept. -

1 June 9, 2014 Dear Upper School Students, As You Plan Your Summer

1 June 9, 2014 Dear Upper School Students, As you plan your summer, don’t forget to plan some time to read. On the next page are the titles of required summer reading, followed by two annotated lists of additional reading. Choose two from the additional lists. You may also choose any other book by the authors on these lists, or other books of literary merit. A good way to know that the book is of high quality is to read what the critics say about it. Are these critics from reputable sources (e.g., New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune)? Another good way to judge the quality of books is to find them in the “literature” section of the bookstore or library. We encourage you to make some of your own choices this summer, but be selective. Ask your friends what they like to read. Ask your parents, your teachers. Also, don’t be afraid to stop reading a book if you don’t like it. Find another one. There are so many good ones; you will eventually find one you like. One of the enclosed annotated lists is compiled from the pre-college reading lists, freshman syllabi, and core programs detailed in Reading Lists for College Bound Students (Estell, Satchwell, and Wright). The titles represent the 100 books most frequently recommended by colleges and universities. We encourage you to read at least one from this list; the more you read from the traditional canon, the more able you will be to compete in college. Please read actively! If you own the book, highlight as you read (e.g., underline, make notes in margins, keep a reading journal). -

DOCUMENT RESUME Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 423 573 CS 509 917 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (81st, Baltimore, Maryland, August 5-8, 1998) .Qualitative Studies. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE 1998-08-00 NOTE 281p.; For other sections of these Proceedings, see CS 509 905-922. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Audience Participation; Case Studies; Critical Theory; Feminism; Genetics; Higher Education; *Journalism; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; *Popular Culture; Qualitative Research IDENTIFIERS Communication Strategies; Community Leadership Program; Horror Films; Maryland; *Media Coverage; Popular Magazines ABSTRACT The Qualitative Studies section of the Proceedings contains the following 10 papers: "An Alternative to Alternative Media'" (James Hamilton); "A Critical Assessment of News Coverage of the Ethical Implications of Genetic Testing" (David A. Craig); "Earth First! and the Boundaries of Postmodern Environmental Journalism" (Rick Clifton Moore); "Social Movement Organization Collective Action Frames and Press Receptivity: A Case Study of Land Use Activism in a Maryland County" (Brian B. Feeney); "Building a Heartline to America: Quiz Shows and the Ideal of Audience Participation in Early Broadcasting" (Olaf Hoerschelmann); "The Cadaverous Bad Boy as Dream-Shadow Trickster: Why Freddy Krueger Won't Let Teens Rest In Peace" (Paulette D. Kilmer) ;"Reframing a House of Mirrors: Communication and Empowerment in a Community Leadership Program" (Eleanor M. Novek); "On the Possibility of Communicating: Critical Theory, Feminism, and Social Position" (Fabienne Darling-Wolf); "Memory and Record: Evocations of the Past in Newspapers" (Stephanie Craft); and "Interior Design Magazines as Neurotica" (Kim Golombisky). -

View of the Literature

PREDICTING URBAN ELEMENTARY STUDENT SUCCESS AND PASSAGE ON OHIO’S HIGH-STAKES ACHIEVEMENT MEASURES USING DIBELS ORAL READING FLUENCY AND INFORMAL MATH CONCEPTS AND APPLICATIONS: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY EMPLOYING HIERARCHICAL LINEAR MODELING A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College and Graduate School of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Erich Robert Merkle December 2010 © Copyright, 2010 by Erich Robert Merkle All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Erich Robert Merkle B.S., Heidelberg College, 1996 M.Ed., Kent State University, 1999 M.A., Kent State University, 1999 Ed.S., Kent State University, 2006 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2010 Approved by ______________________________ Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Caven S. Mcloughlin ______________________________ Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Frank Sansosti ______________________________ Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Jason D. Schenker Accepted by ______________________________ Director, School of Lifespan Development and Mary Dellmann-Jenkins Educational Sciences ______________________________ Dean, College and Graduate School of Daniel F. Mahony Education, Health and Human Services iii MERKLE, ERICH R., Ph.D., December 2010 School Psychology PREDICTING URBAN ELEMENTARY STUDENT SUCCESS AND PASSAGE ON OHIO’S HIGH-STAKES ACHIEVEMENT MEASURES USING DIBELS ORAL READING FLUENCY AND INFORMAL MATH CONCEPTS AND APPLICATIONS: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY EMPLOYING HIERARCHICAL LINEAR MODELING (180 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Caven S. Mcloughlin, Ph.D. Contemporary education is experiencing substantial reform across legislative, pedagogical, and assessment dimensions. The increase in school-based accountability systems has brought forth a culture where states, school districts, teachers, and individual students are required to demonstrate their efficacy towards improvement of the educational environment. -

Questions to Ask When Examining a Position

QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN EXAMINING A POSITION It is vital to learn how to evaluate an argument calmly levels of aggression, rape, and child abuse in the same and objectively. Discussing the following questions will way that one sees in caged animals” contains elements of help. These questions will enable you to break down an both opinion and fact. argument into its component parts, thereby avoiding the •Question: What Propaganda Is Being Used? common tendency to be swayed by a presenter’s delivery techniques or by one’s own set of biases and opinions. Propaganda is information presented in order to influ- ence a reader. It is not necessarily “good” or “bad.” Many •Question: How Empirical Is the Presentation? authors consciously use propaganda techniques in order The most persuasive argument is the one that supports to convince their readers of their special point of view. A its thesis by referring to relevant, accurate, and up-to-date close look at the author’s background or some of the data from the best sources possible. One should investi- motivations and editorial policies of the source of the gate the credibility of the author, how recent the material publication may provide clues about what types of pro- is, the type of research (if any) that supports the position paganda techniques might be used. outlined, and the degree of documentation behind any •Question: What Cause/Effect Relationships Are Proposed? argument. Empiricism implies going to the best source for material. This suggests that original research material Much material is written to establish or advance a is preferable to secondary sources, which in turn are hypothesis that some circumstances “cause” specific preferable to hearsay.