History of the Black Panther Party—Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

50Th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr

50th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr. Jakobi Williams: library resources to accompany programs FROM THE BULLET TO THE BALLOT: THE ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND RACIAL COALITION POLITICS IN CHICAGO. IN CHICAGO by Jakobi Williams: print and e-book copies are on order for ISU from review in Choice: Chicago has long been the proving ground for ethnic and racial political coalition building. In the 1910s-20s, the city experienced substantial black immigration but became in the process the most residentially segregated of all major US cities. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, long-simmering frustration and anger led many lower-class blacks to the culturally attractive, militant Black Panther Party. Thus, long before Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, made famous in the 1980s, or Barack Obama's historic presidential campaigns more recently, the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party (ILPBB) laid much of the groundwork for nontraditional grassroots political activism. The principal architect was a charismatic, marginally educated 20-year-old named Fred Hampton, tragically and brutally murdered by the Chicago police in December 1969 as part of an FBI- backed counter-intelligence program against what it considered subversive political groups. Among other things, Williams (Kentucky) "demonstrates how the ILPBB's community organizing methods and revolutionary self-defense ideology significantly influenced Chicago's machine politics, grassroots organizing, racial coalitions, and political behavior." Williams incorporates previously sealed secret Chicago police files and numerous oral histories. Other review excerpts [Amazon]: A fascinating work that everyone interested in the Black Panther party or racism in Chicago should read.-- Journal of American History A vital historical intervention in African American history, urban and local histories, and Black Power studies. -

And at Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2018 And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Linda, "And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 450. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/450 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of San Francisco And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International and Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment For the Requirements for Degree of the Doctor of Education by Linda Garrett, MA San Francisco May 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT AND AT ONCE MY CHAINS WERE LOOSED: HOW THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY FREED ME FROM MY COLONIZED MIND The Black Panther Party was an iconic civil rights organization that started in Oakland, California, in 1966. Founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Party was a political organization that sought to serve the community and educate marginalized groups about their power and potential. -

PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the THIRD CIRCUIT No. 06-2241 MARAKAY J. ROGERS, Esquire, Candidate for Governo

PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT No. 06-2241 MARAKAY J. ROGERS, Esquire, Candidate for Governor of Pennsylvania; THE GREEN PARTY OF PENNSYLVANIA, c/o Paul Teese, Chair; THE CONSTITUTION PARTY OF PENNSYLVANIA; KEN V. KRAWCHUK; HAGAN SMITH, Appellants. v. THOMAS W. CORBETT, JR., Attorney General of Pennsylvania; COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, c/o Office of the Attorney General of Pennsylvania; GOVERNOR EDWARD G. RENDELL; PEDRO A. CORTES, Secretary of Commonwealth of Pennsylvania On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania District Court No. 06-cv-00066 District Judge: Hon. John E. Jones, III Argued on July 10, 2006 Panel Rehearing Granted November 3, 2006 Before: SMITH, ALDISERT, and ROTH, Circuit Judges (Opinion filed: November 3, 2006) O P I N I O N Samuel C. Stretton, Esquire (Argued) 301 South High Street P. O. Box 3231 West Chester, PA 19381-3231 Counsel for Appellants Thomas W. Corbett, Jr., Esquire Attorney General Howard G. Hopkirk, Esquire (Argued) Senior Deputy Attorney General John G. Knorr, III, Esquire Chief Deputy Attorney General Chief, Appellate Litigation Section Office of the Attorney General of Pennsylvania Strawberry Square, 15th Floor Harrisburg, PA 17120 Counsel for Appellees ROTH, Circuit Judge: Plaintiffs, a group of minor political parties and minor party nominees for state-wide office,1 challenged the constitutionality of Section 2911 of the Pennsylvania election code, 25 PA. CONS. STAT. § 2911(b), as applied to minor political parties and their candidates. They moved for a 1Plaintiffs are Marakay Rogers, Esq., the Green Party candidate for Governor in the November 2006 general election; the Green Party of Pennsylvania; Hagan Smith, the Constitution Party candidate for Governor; the Constitution Party of Pennsylvania; and Ken V. -

The Joker: Gotham’S Phoenix’S Gritty ‘Joker’ Drives Critics Crazy Clown Prince of Crime

Established 1961 21 Lifestyle Movies Monday, September 2, 2019 (From left) German US actress Zazie Beetz, US actor Joaquin Phoenix, US director Todd Phillips and US producer Emma Tillinger (From fifth left) German US actress Zazie Beetz, US actor Joaquin Phoenix and US director Todd Phillips and guests attend a photocall for the film ‘Joker’ presented in competition during the 76th Venice Film Festival at Venice Lido. — AFP photos arrive for the screening of the film “Joker”. The Joker: Gotham’s Phoenix’s gritty ‘Joker’ drives critics crazy clown prince of crime oaquin Phoenix’s visceral performance as the down- trodden street clown who transforms into the “Joker” rom playing-card caricature to diabolical super- Jwas hailed by critics as “sensational” and “unnerving” villain, the Joker has been reincarnated by a rosta on Saturday, as his pitch-black supervillain origin story Fof Hollywood stars in his near eight decades on premiered at the Venice film festival. Phoenix reimagines the mean streets of Gotham, with each era painting its one of cinema’s most recognizable villains in the film, with own mark on the grinning Batman nemesis. The chaos- the story of Arthur Fleck, a vulnerable loner struggling to loving prankster, with his clown make-up and rictus survive in the rage-scorched streets of Gotham. Todd grin, first appeared in comic books in 1940 and has Phillips, known for frat house comedies including the made regular appearances on screen since the 1960s. “Hangover” trilogy and “Road Trip”, set the film in the Most famously played by Jack Nicholson and Heath 1970s as a nod to the brooding cinematic character studies Ledger, the character has had countless cameos in of the time, like “Taxi Driver” and “The King of Comedy”. -

Karenga's Men There, in Campbell Hall. This Was Intended to Stop the Work and Programs of the Black

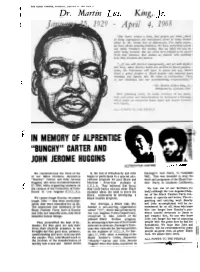

THE BLACK P'"THRR. """0". J'"""V "' ,~, P'CF . ,J: Dr. Martin - II But there comes a time, that. peoPle get tired...tired of being segregated and humiliated; tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression. For many years, we have shown amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice. "...If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and love, when history books are written in future genera- tions, the historians will have to pause and say, 'there lived a great peoPle--a Black peoPle--who injected new meanir:&g and dignity into the veins of civilization.' This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility." t.1 " --Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Montgomery, Alabama 1956 With pulsating voice, he made mockery of our fears; with convictlon and determinatlon he delivered a Message which made us overcome these fears and march forward with dignity . ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE \'-'I'; ~ f~~ ALPRENTICE CARTER JOHN HUGGINS We commemorate the lives of two In the fall of 1968,Bunchy and John Karenga's men there, in Campbell of our fallen brothers, Alprentice began to participate in a special edu- Hall. This was intended to stop the "Bunchy" Carter and John Jerome cational program for poor Black and work and programs of the Black Pan- Huggins, who were murdered J anuary Mexican -American students at ther Party in Southern California. -

All Power to the People! the Black Panther Party and Beyond (US, 1998, 115 Minutes) Director: Lee Lew Lee Study Guide

All Power To The People! The Black Panther Party and Beyond (US, 1998, 115 minutes) Director: Lee Lew Lee Study Guide Synopsis All Power To The People! examines problems of race, poverty, dissent and the universal conflict of the “haves versus the have nots.” US government documents, rare news clips, and interviews with both ex-activists and former FBI/CIA officers, provide deep insight into the bloody conflict between political dissent and governmental authority in the US of the 60s and 70s. Globally acclaimed as being among the most accurate depictions of the goals, aspirations and ultimate repression of the US Civil Rights Movement, All Power to the People! Is a gripping, timeless news documentary. Themes in the film History of the Civil Rights Movement Black Panther Party FBI’s COINTELPRO American Indian Rights Movement Political Prisoners in the US Trials of political dissidents such as the Chicago 7 trial Study Questions • Why did the FBI perceive the Black Panther Party as a threat? • How did the FBI’s COINTELPRO contribute to the destruction of the Black Panther Party? • What do you know about Fred Hampton? • Can you name any former members of the Black Panther Party? • Throughout US history, what are some of the organizations that have been labeled as “troublemakers” by the FBI? • In your opinion, why were these groups the target of FBI investigations and operations such as COINTELPRO? • Do you think this kind of surveillance and disruption of dissent exists today? • In this film, we see clips of leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and Huey Newton. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: from Revolution to Reform, a Content Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2018 The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis Michael James Macaluso Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Macaluso, Michael James, "The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis" (2018). Dissertations. 3364. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3364 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLACE OF ART IN BLACK PANTHER PARTY REVOLUTIONARY THOUGHT AND PRACTICE: FROM REVOLUTION TO REFORM, A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Michael Macaluso A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Western Michigan University December 2018 Doctoral Committee: Zoann Snyder, Ph.D., Chair Thomas VanValey, Ph.D. Richard Yidana, Ph.D. Douglas Davidson, Ph.D. Copyright by Michael Macaluso 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. Zoann Snyder, Dr. Richard Yidana, Dr. Thomas Lee VanValey, and Dr. Douglas Davidson for agreeing to serve on this committee. Zoann, I want thank you for your patience throughout this journey, I truly appreciate your assistance. Richard, your help with this work has been a significant influence to this study. -

Peoples News Service

4r ' SOTRIOvol. 1 NO. JcV^TV MARfM '21, ;v70 PATRIOT PARTY MiNISTRY OF INFORMATiON 1742 IHD AV£, NEW rom^ PEOPLES NEWS SERVICE WE ARE THE UVRlK^ REMINDER THAT WHEN THEY THREW OUT THEIR WHITE TRASH THEY DIDNt BURN IT" PREACHERMAN THE PATRIOT, MARCH 21» 1970. PAGE Z The South will rise again, only this time with the North, and all oppressed people throughout the world. RATRIOT PROGRAM. The Patriot Party Program is a Peoples' Program. The to the fact that they can take care of their own medical WHAT WE DEMAND Program of the Patriot Party is a Program of oppressed needs. All the Peoples' Programs are part of the white people of the United States. The 10 Point community and eventually will be run and expanded Program came from the people themselves. The people and enlarged by the people themselves. This is how the 1. We demand freedom. We demand power were asked, "What is it that you want? that you need? Party educates the people - not by talking about our to determine the destiny of our oppressed that you desire to see?" and the people answered. What ideas, but acting on them. We know it is better for the people answered was based on their real life people to cooperate with one another than compete white community. experiences. The peoples' answers are based on the day with one another. The people learn through to day reality of their lives. And the reality of the participation and observation that it is better to peoples' lives is reality made up of not enough to eat, cooperate with one another than to compete. -

War Against the Panthers: a Study of Repression in America

War Against The Panthers: A Study Of Repression In America HUEY P. NEWTON / Doctoral Dissertation / UC Santa Cruz 1jun1980 WAR AGAINST THE PANTHERS: A STUDY OF REPRESSION IN AMERICA A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS by Huey P. Newton June 1980 PREFACE There has been an abundance of material to draw upon in researching and writing this dissertation. Indeed, when a friend recently asked me how long I had been working on it, I almost jokingly replied, "Thirteen years—since the Party was founded." 1 Looking back over that period in an effort to capture its meaning, to collapse time around certain significant events and personalities requires an admitted arbitrariness on my part. Many people have given or lost their lives, reputations, and financial security because of their involvement with the Party. I cannot possibly include all of them, so I have chosen a few in an effort to present, in C. Wright Mills' description, "biography as history." 2 This dissertation analyzes certain features of the Party and incidents that are significant in its development. Some central events in the growth of the Party, from adoption of an ideology and platform to implementation of community programs, are first described. This is followed by a presentation of the federal government's response to the Party. Much of the information presented herein concentrates on incidents in Oakland, California, and government efforts to discredit or harm me. The assassination of Fred Hampton, an important leader in Chicago, is also described in considerable detail, as are the killings of Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter and John Huggins in Los Angeles. -

Still Black Still Strong

STIll BLACK,STIll SfRONG l STILL BLACK, STILL STRONG SURVIVORS Of THE U.S. WAR AGAINST BLACK REVOlUTIONARIES DHORUBA BIN WAHAD MUMIA ABU-JAMAL ASSATA SHAKUR Ediled by lim f1elcher, Tonoquillones, & Sylverelolringer SbIII01EXT(E) Sentiotext(e) Offices: P.O. Box 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031 Copyright ©1993 Semiotext(e) and individual contributors. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 978-0-936756-74-5 1098765 ~_.......-.;,;,,~---------:.;- Contents DHORUDA BIN W"AHAD WARWITIllN 9 TOWARD RE'rHINKING SEIl'-DEFENSE 57 THE CuTnNG EDGE OF PRISONTECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM. RAp AND REBElliON 103 MUM<A ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsON-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 P ANIllER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PRISONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BLACK POLITICALPRISONERS 272 Contents DHORUBA BIN "W AHAD WAKWITIllN 9 TOWARD REnnNKINO SELF-DEFENSE 57 THE CurnNG EOOE OF PRISON TECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM, RAp AND REBEWON 103 MUMIA ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsoN-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 PANTHER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PJusONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRmUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BUCK POLITICAL PRISONERS 272 • ... Ahmad Abdur·Rahmon (reIeo,ed) Mumio Abu·lomol (deoth row) lundiolo Acoli Alberlo '/lick" Africa (releosed) Ohoruba Bin Wahad Carlos Perez Africa Chorl.. lim' Africa Can,uella Dotson Africa Debbi lim' Africo Delberl Orr Africa Edward Goodman Africa lonet Halloway Africa lanine Phillip.