Sacramento Region Local Market Assessment

for the

Sacramento Area Council of Governments

and the

Rural Urban Connections Strategy

prepared by

Agriculture in Metropolitan Regions (AMR)

U.C. Berkeley

with

Valley Vision

and

SAGE (Sustainable Agriculture Education)

DRAFT

December 17, 2008

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- 1

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

2

2

1.2 Methodology Overview

2

2.0 FOOD CONSUMPTION

2.1 Key Findings

2

222222

2.2 Introduction 2.3 Food Consumption in the Greater Sacramento Region 2.4 Beyond Commodities and Per Capita Consumption: What the Data Don’t Tell Us 2.5 Local Affinities for Local Foods 2.6 Healthy and Local?

- 3.0 FOOD DISTRIBUTION

- 2

22222222

3.1 Key Findings 3.2 Introduction 3.3 How it Works: An Overview of Food Distribution Sectors 3.4 Food Distribution Sectors 3.5 Sector-by-Sector Breakdown 3.6 Straight from the Farm: The Direct Sales Landscape 3.7 Food Flows in and out of the Region 3.8 Niche Market Distribution: Organic, Ethnic, and Small Farmer Foods

4.0 MARKETING CONNECTIONS

4.1 Key Findings

2

2222

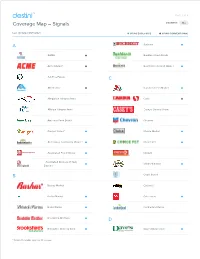

4.2 Introduction 4.3 “Buy Local” Campaigns 4.4 Branding and Labeling Efforts: “Locally Grown” and Beyond 4.5 Virtual Connecters

22

4.6 Other Connectors – Focus on Education

- 5.0 AGRITOURISM

- 2

2222222

5.1 Key Findings 5.2 Agritourism Overview 5.3 SACOG Region: Extent of Agritourism Operations 5.4 SACOG Region: Profiles of Agritourism 5.5 SACOG Region: Regulatory Environment 5.6 SACOG Region: Economics of Agritourism 5.7 Promotion of Locally Grown Food in the SACOG Region

6.0 LOCAL PERSPECTIVES - OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES TO EXPAND

- THE REGION’S LOCAL FOOD SYSTEM

- 2

2222

6.1 Key Findings 6.2 Challenges Affecting the Expansion of Local Foods within the Region’s Marketplace 6.3 Opportunities for Expanding the Local Food System 6.4 Ideas for Innovations

Executive Summary

Over the last several years, there has been a growing interesting among consumers about the source of their food. What started as demand for “organic” food has evolved to demand for “locally- and sustainably-produced” food. Some people are concerned with food safety, others about taste and freshness, some with environmental benefits, while others view local food production as a vestige of our heritage worth preserving and enhancing. For producers, their customers’ concerns and interests are their own concerns and interests, provided that meeting these objectives correlates with meeting their financial bottom line. While enterprises and a body of literature have developed around the local food niche, there is a shortage of data to understand the impact of this movement on food systems in the SACOG region. Nonetheless, there are plenty of local market examples in each county in the region – some of which were seen on agriculture tours for the SACOG Board of Directors throughout 2008 – and enough interest with producers, retailers, and distributors in addition to consumers, that an entire working group for the Rural-Urban Connections Strategy project has been formed to better understand the opportunities for local markets and agritourism. These opportunities are part of the larger topic of new economic opportunities in agriculture and present a possible new revenue stream for farmers and ranchers.

To understand the challenges to fostering a market for local food, we need to first understand how today’s food system works. Generally, we have a food system that has evolved to support largescale agriculture and large retailers. Food is trucked into and out of the region daily since the bulk of the production in the region meets very little of our demand. And even where we do grow enough of one crop or another, the conventional food system is not well suited to channel sufficient amounts of that crop directly to meet the local consumer demand. This disconnect means that “food flows” are more extensive than they might be if local demand was better served with local production. However, local food systems are already being seen by the increasing popularity of farmers markets, Community Supported Agriculture boxes, agritourism, and nascent demand at restaurants, schools, and other institutions. The extent to which these venues and others become markets for local food requires further analysis. The RUCS team with the help of the Local Market and Agritourism working group is delving into this question, as well as trying to better understand how this market opportunity affects transportation and land use needs to support it. This paper begins to help the region better understand the current food system and the challenges and opportunities to promoting a local food system.

What we produce and what we consume

Food is produced in abundance in the SACOG region. Overall, the region produces over 3.4 million tons of food annually. Based on USDA data, we can estimate that the SACOG region consumes 2.2 million tons of food annually. Breaking this down by county, three of the six counties in the SACOG region consume more than they produce by weight: Sacramento County (~twice as much), El Dorado (~41 times as much), and Placer County (~six times as much). Yolo, Sutter, and Yuba

Counties each produce around eight times more food than their residents consume by weight.

However, when we consider product-specific production, there are notable imbalances. While regional production of vegetables equals 1,812,834 tons annually, 93% of that number is in tomato production alone, much of which leaves the region for processing. Of the 760,320 tons of grain produced in the region, 90% of that is in rice production. However, the vast majority of that rice is exported to Asia and the Middle East, sold domestically as table rice, or used in industrial processes

1DRAFT 12/18/2008

Sacramento Region Local Market Assessment

1or rice products (i.e. Rice Krispies). The region actually consumes less than 2% of the rice produced here. Finally, in the category of meat and eggs, the region consumes a whopping 1,262% compared to what it produces, meaning this food sector is served almost exclusively by products transported into the region via truck or train. This imbalance between the types of food the region consumes and the foods we produce might present a new local market opportunity for farmers and ranchers, as long as barriers within the local foods distribution system could be adequately addressed.

Distribution

The food distribution system in the region is very efficient for moving food in and out of the region, but not necessarily for moving food from producer to consumer within the region. The system is geared towards larger scale commercial operations and larger scale movement of food. For smaller or mid-size producers, the distribution system may not be quite as user friendly, particularly for those producers focused on local distribution. Additionally, increased consolidation of grocers and wholesalers has resulted in a reduced number of the outlets that focus on selling of locally-produced foods. An increase in sourcing food locally will need distribution systems geared toward the local producer as discussed below. The implications of local food distribution system on the transportation system will need further study, however, the general construct draws from an analogy to the Blueprint where a prime objective of bring jobs and housing closer together is to reduce vehicle miles of travel. For food systems, the closer the producer is to the consumer, the fewer “food miles” of travel.

Consumer demand?

While the limited scope of local food comes from several causes, one primary cause repeatedly arose during this research: lack of demand. Education gaps about the benefits and availability of local foods hinders expansion of the system. Also, local often means organic, which increases the cost throughout the system, particularly at the consumer end. Lack of consumer demand has also affected data gathering within the distribution system. Even for distributors who have expressed a desire to track the origin and provenance (defined as…..) of the food they supply, the system does not easily enable this type of accounting. A lack of demand means there’s no pressure at any given point to change tracking in any part of the system.

Successes

But there are promising signs on the horizon. Increases in customer volume at area farmer’s markets along with increased participation in Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), suggest a rising interest in purchasing locally-produced food. A robust agritourism sector and successful branding campaigns speak to the desire of urban dwellers to increasingly reconnect with the region’s agricultural heritage. And passage of local ordinances and state regulations like AB 2168 that support direct marketing of agricultural products are early indications of legislative movement towards supporting a more sustainable food system.

Challenges and Opportunities

There are specific challenges that need to be overcome in order to expand the local food system, and there are opportunities we could seize upon that could change the current reality.

Education gaps and education opportunities for consumers. While gaps in consumer education may

be a primary cause of the lack of scope of local foods, these gaps present an opportunity for the region. This includes increasing educational opportunities for consumers, chefs, and grocery store produce buyers to learn where to buy local, health benefits of buying local, what’s in season, and how to use seasonal produce. Additionally, the region can build on the success of existing farm visit programs for school groups and increase the number of children participating on hands-on farm experiences.

Helping farmers find the right niche. Farmers often cited trouble with finding the right fit for themselves within the distribution system and developing the necessary skill set to establish a direct marketing enterprise. Educating farmers about opportunities, and providing systematic guidance on how and where to step into the distribution system could boost the farming community’s investment in the local food system. Likewise, certain niches within the region remain unfilled and there needs to be more awareness of the market opportunity. Several larger institutions, like school districts, hospital systems and casinos, have complained that there are not locally-serving farms that are big enough to provide a reliable supply of foods to fit their needs.

Creating new distribution and processing infrastructure. Some of the challenges with the current

distribution system could be solved by creating new locally-focused distribution infrastructure, like shared processing facilities and distribution centers. This would help network local farms to meet the demands of larger markets. It would also provide a clear avenue for farmers wanting to sell their products to the regional market.

The implications of our research suggest that there is currently not an efficient means of getting food from our rural areas to our urban areas. Most small to mid-size farms in the region aren’t coordinated in delivering their produce to the urban areas. Individual deliveries increase fuel costs and time spent away from the farm. This problem is in part a distribution problem—the lack of a centralized distribution point in the urban areas—but is also due to the difficulties of getting larger trucks onto rural roads. Agritourism venues face their own difficulties around transportation with increased traffic on rural roads, particularly during peak agritourism season in the fall.

Further regulatory changes. Farmers face hurdles in following local regulatory requirements from health department regulations in providing on-farm experiences and activities, to navigating licensing and permitting requirements that are often geared towards large-scale production. Recent successes at the local and state level that support local farmers can be built on to ease regulatory barriers.

Additional opportunities raised during this research include: creating economic incentives for farmers to sell local; “retooling” the cooperative extension farm advisor program to make it better serve locally-focused agriculture; creating online networking opportunities for producers, distributors, and processors; and expanding local agricultural branding efforts.

Land use issues. Land use issues are central to the entire RUCS project. Interviewees and workshop participants in the Local Markets piece talked about the problems of increased subdivision of farm and ranch lands; the challenge of keeping land in agriculture as older generations retire and younger generations can’t afford to purchase land; the struggles that immigrants and refugees face when leasing land to farm due to their lack of resources for purchasing land; and the difficulties of finding funding for conservation and agriculture easements.

Another land use issue is land supply. As noted earlier, the region consumes 2.2 million tons of food a year, while it produces 3.4 million tons. Barring the aforementioned disconnect between production and demand and food flows, it appears that the potential volume produced in a local food system could meet demand for many food items in the region. However, that is based on an analysis of today’s demand; with a roughly doubling of the population by 2050, the land supply needed for production to meet that demand needs to be better understood. Modeling capacity that SACOG is developing may be able to start answering that question.

Labor issues. Farmers in the SACOG region face the challenge of finding an adequate supply of skilled labor, as well as learning how to manage the diverse staffing demands that are unique to an agritourism operation. An adequate supply of labor is particularly difficult during harvest seasons due to the competing needs not only of each county, but each orchard at times. Smaller orchards may have difficulty retaining labor when larger orchards can guarantee more work, likewise for vineyards in the region.

1.0 Introduction

On the map, the greater Sacramento Region resembles two worlds. The state capital lies in the belly of a vast swath of urban and suburban development, extending out from the banks of Sacramento River and spreading eastward into the Sierra foothills. In contrast, farms, orchards, and ranches cover much of the western half of the six-county region.

The two are not as irreconcilable as they might seem. Farmers and ranchers of Sutter, Yolo, Yuba, and to the lesser degree El Dorado, Placer, and Sacramento counties raise crops and livestock that provide sustenance and bring gustatory pleasure to tables as near as Roseville on the I-80 corridor and as far as Syria, in the Middle East.

Food is the fundamental linkage between the countryside and the city. The bountiful, diverse agriculture and the growing population of the SACOG region optimize the potential for this ruralurban linkage through food. Farm-fresh produce, meat, and grain can nourish regional residents and bolster healthful diets, reducing demands on the health care system in the long-term. Marketing of regional food to stores, restaurants, schools, and other outlets in the six counties can also help increase income for local farmers and ranches. In addition, increasing production and consumption from within the close-by food shed can put the region on the path toward greater sustainability, reducing fossil fuel consumption, traffic congestion, and air pollution and promoting linked urbanrural public health.

In the following chapters of the Local Market Assessment, we use three lenses to explore the potential to strengthen the connections between rural, urban, and suburban residents through food: the consumption of food, food distribution, and farmer-to-consumer marketing of food.

- 1.1

- Background

The Sacramento Council of Governments (SACOG) is in the process of implementing its awardingwinning Sacramento Region Blueprint and the Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP), which will guide how the region grows and makes transportation investments. Built on principles of smart growth, the Blueprint includes a wide range of housing products, reinvestment in already developed areas, protection of natural resource areas, and more transportation choices. The MTP is underpinned by the Blueprint and calls for transportation investments that support smart growth strategies.

To address impacts to agricultural resources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the environmental Impact Report for the MTP includes a mitigation measure to develop a Rural-Urban Connections Strategy (RUCS). The RUCS aims to develop tools and strategies that foster economic and environmental sustainability in rural areas and that support the sustainability and resilience of the Sacramento Region overall. The RUCS has five topic areas: •••••

Land Use and Conservation: Policies and Plans That Shape Rural Areas The Infrastructure of Agriculture: Challenges to the Production Process Economic Opportunities: New Ways to Grow Revenue Forest Management: Firing up Economic and Environmental Value Regulations: Navigating Federal and State Environmental Guidelines

The Sacramento Region Local Market Assessment represents the first phase of research for the Economic Opportunities: New Ways to Grow Revenue topic area. The purpose of the Local Market Assessment is to document the potential of agriculture in the Sacramento region to increase its own sustainability and the sustainability of the region, by directly supplying more of the region’s nutritional needs and other public benefits.

Agriculture and food are a critical focus for the Rural-Urban Connection Strategy. Agriculture is the starting point because it is the region’s major non-urban land use, is currently vulnerable to a range of economic pressures (local to global), and yet has the enormous impact across multiple sectors. Multifunctional and multi-faceted, agriculture involves land use, transportation, energy, air and water quality, bio-diversity, cultural diversity, public health, and of course food production. When given a local-place-based and ecological-systems-based focus, agriculture has the potential to meet or complement key environmental, social, and economic goals for sustaining metropolitan regions.

Food is produced in abundance in the SACOG region. However, because the geography of food production and distribution has become global, the Sacramento Region, like most metropolitan areas, to date has paid insufficient attention to the current conditions of – let alone a preferred scenario for - its own foodshed. Just as the Blueprint looked at the urban form and basic needs for shelter and transportation, now the Local Market Assessment now brings to the foreground, another fundamental element of the region’s well-being: food. In investigating food consumption, production, distribution, and marketing and the marketing of agriculture itself through agtourism, the Assessment presents numerous strands of economic, geographic, and demographic data. Most importantly, the Assessment underscores the need for a systems-based understanding of regional food and agriculture as an integral element for understanding and fostering the sustainability of the region.

- 1.2

- Methodology Overview

The first draft of the Local Market Assessment represents the combined efforts of Agriculture in Metropolitan Regions (AMR), Sustainable Agriculture Education (SAGE), and Valley Vision. This report was compiled through interviews with regional stakeholders and data analysis of the region’s six-county food system. It includes an assessment of the current conditions in the food consumption, distribution, marketing and agritourism segments of the region’s extensive food system. The appendices include data from all the report segments. There will be some additions to this first draft as some scheduled interviews remain, and some data is forthcoming, such as a typology of diversified farms in the region.