Emotions As Objects of Argumentative Constructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Abstract Book of the Conference

FULL ABSTRACT BOOK 9th MIDTERM CONFERENCE ON EMOTIONS RN 11 “Sociology of Emotions” of the European Sociological Association (ESA) 25th–27th November 2020, online Website of the Conference: https://www.ub.edu/emotions20/ * Please, notice all times are CET. KEYNOTE LECTURES Friday, November 27th, 19-20 pm: Arlie Russell Hochschild University of California Berkeley Battle of Deep Stories and the American Election In any political struggle, one theatre of struggle is that of a legitimating “righteous story.” Focusing on the American Republican right, in this talk, Hochschild will discuss three things, a) the basic right wing deep story of blacks, women, public officials “cutting ahead” in line ahead of rule-abiding, hard-working but stuck line-waiters. She also analyzes the additional “chapters” to this story drawn from current events (eg our chosen leader will liberate us, he is under assault, etc), b) the powerful appeal of the presidential story-teller and c) the steps taken in the presidential reach for power – (incrementalism, adding a lightness to serious norms regarding violence, focus on personal loyalty, etc). She will conclude with ideas for best next steps. Thursday, November 26th, 16.30-18 pm: Amparo Lasén Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain Digital Mediations and Inscriptions of Ordinary Affects: Shame and Shaming Our ordinary lives, bodies, memories, relationships, fantasies, desires, affects and fears flow and inhabit different spaces, media and digital platforms, giving rise to narratives, self-(re)presentations and interactions shaped by a networked shared agency of heterogeneous participants. A networked collective of people, devices, corporations, and institutions take part in the production and archiving of digital inscriptions, which materialise our emotions and contribute to the configuration and inscription of our bodies, habits, and abilities. -

Staging Poetic Justice

臺大文史哲學報 第六十五期 2006年11月 頁223~250 臺灣大學文學院 Staging Poetic Justice: Public Spectacle of Private Grief in the Musical Parade Wang, Pao-hsiang∗ Abstract This paper makes inquiries into the 1998 musical Parade by playwright Alfred Uhry and composer Jason Robert Brown, based on the historic case of Leo Frank, a Jewish industrialist from New York running a pencil factory in Atlanta and accused of murdering the 13-year-old girl Mary Phagan in 1913. How can the thorny case be represented with any fidelity on stage when all the facts have not come to light? What can a theatre researcher contribute to or comment on a controversial production of a reproduction of a historical incident that has never ceased to produce great furors over the past 90 years? In the absence of irrefutable legal evidence that could close the case and in the face of contending camps that claim justice on each side, the author will stay above the litigation fray and distance himself from any attempt to pass judgment on the innocence or guilt of people involved in the historic case. Rather, the paper first probes the context surrounding the case, including war, class, race, and to a lesser extent, sexuality by examining it from the perspective of historical legacy, such as the post-bellum South reeling from the repercussions of the Civil War defeat, the regional animosity between the highly industrialized North and New Industrial South, the class antagonism of management and labor in the pencil factory, the ethnic strife between blacks, whites, and Jews, and the conventional bias against the perceived sexual perversion of Jews and blacks. -

Emotionally Appealing Ads May Not Always Help Consumer Memory 7 January 2021, by Phil Ciciora

Emotionally appealing ads may not always help consumer memory 7 January 2021, by Phil Ciciora appeals on consumers' memory has always been a bit unclear," Noel said. "So we examined the impact of different aspects of emotionally arousing ads on memory. Why did we focus on emotion? Well, in the majority of business-to-consumer ads that are crafted to drive sales, eliciting emotional activation, or arousal, plays a critical role." In three experiments using print and video ads from different English-speaking countries, Noel and co- author Hila Riemer of Ben Gurion University of the Negev tested the moderating roles of retention time and the fit between the emotional arousal communicated in the ad and the ad claim. All experiments used combinations of low- and high- Emotional appeals in advertisements may not always emotionally arousing ads. help improve consumers’ immediate recall of a product, says a new paper co-written by Hayden Noel, a clinical The researchers found that when the level of associate professor of business administration at the emotional activation elicited by the ad doesn't fit the Gies College of Business at Illinois. Credit: Gies College ad's claim, then the message conveyed ultimately of Business doesn't stick in the consumer's mind. "It's an examination of boundary conditions under which you can maximize the use of emotional In almost all successful advertising campaigns, an appeals," Noel said. "And the role of retention time appeal to emotion sparks a call-to-action that shows that low-arousal stimuli are better motivates viewers to become consumers. -

Logos Ethos and Pathos

Logos, Ethos, and Pathos Whenever you read an argument, you must ask yourself, “Is this persuasive? And if so, to whom?” There are several ways to appeal to an audience. Among them are appealing to logos, ethos, and pathos. These appeals are prevalent in almost all argument. Definitions Logos The Greek word “logos” is the basis for the English word “logic.” Logos is a broader idea than formal logic—the highly symbolic and mathematical logic that you might study in a philosophy course. Logos refers to any attempt to appeal to the intellect, the general meaning of “logical argument.” Everyday arguments rely heavily on ethos and pathos, but academic arguments rely more on logos. Yes, these arguments will call upon the writers’ credibility and try to touch the audiences’ emotions, but there will more often that not be logical chains of reasoning supporting all claims. Ethos Ethos is related to the English word “ethics” and refers to the trustworthiness of the speaker/writer. Ethos is an effective, persuasive strategy because when we believe that the speaker does not intend to do us harm, we are more willing to listen to what he/she has to say. For example, when a trusted doctor gives you advice, you may not understand all of the medical reasoning behind the advice, but you nonetheless follow the directions because you believe that the doctor knows what he/she is talking about. Likewise, when a judge comments on legal precedent, audiences tend to listen because it is the job of a judge to know the nature of past legal cases. -

Shaming Into Argumentation

ISSA Proceedings 2006 – Shaming Into Argumentation 1. Introduction I submit that appeals to shame, here defined as a concern for reputation, may be not only relevant to but make possible argumentation with reluctant addressees. Traditionally emotional appeals including shame appeals have been classified as fallacies because they are failures of relevance (Govier 2005, p. 198; van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1992, p. 134); we ought to believe or act based on the merits of a case rather than because we feel shame or some other emotion. However, Walton (1992, 2000) among others has argued that emotional appeals are not inherently fallacious, that they may also be strong or weak arguments, and that critics ought to evaluate them based on the inferential structure of the practical reasoning they involve as well as on the type of dialogue in which they occur. In what follows I aim to build on Walton’s insights that critics ought to attend to the practical reasoning involved in and the context of emotional appeals. Specifically, I argue, first, that to analyze and evaluate emotional appeals critics ought to attend to the discourse strategies that arguers actually use rather than relying on reconstructions alone. Second, I argue that to analyze and evaluate emotional appeals critics ought to consider context more broadly than the type of dialogue. Doing so enables critics to assess proportion in emotional appeals as well as the practical reasons they create, and to better understand complex argumentation such as political discourse. 2. Attending to actual discourse strategies When analyzing and evaluating emotional appeals, critics ought to attend to the discourse strategies arguers actually use rather than relying on reconstructions only for two main reasons. -

Change My Mind Teacher Guide

Teacher Guide http://www.pbs4549.org/changemymind Table of Contents Credits...................................................................................4 Using Persuasive Techniques ........... 39 Change.My.Mind:.Overview..............................................5 The.Hidden.Power.of.Connotations..................................41 Connotations............................................................... 45 Three.Considerations.When.Trying.to.Persuade...............6 Persuasive.Writing.Strategies.and.Techniques...................7 Slogans.and.Symbols.in.Commercials............................ 46 Slogans.and.Symbols:.Transfer................................. 48 Persuasion.Terminology.....................................................11 The.Power.of.Transfer................................................. 49 Celebrity.Power................................................................. 50 Learning Persuasive Techniques .......15 P..Diddy....................................................................... 52 Introduction.to.Rhetorical.Strategies.and.. Product.Comparison................................................... 53 Persuasive.Techniques........................................................17 Appeal.to.Authority.....................................................19 Rhetorical.Strategies.—.Appeals.to.Authority,.Emotions,. Appeal.to.Emotion...................................................... 20 Ethics.and.Logic................................................................. 54 Controversial.Topics.................................................. -

Emotion Appeals Made Me Buy It! but Which?

Emotion appeals made me buy it! But which? Author: Danissa van Hattem Department: MCB Course code: YSS-81812 Attendant 1: Ilona de Hooge Attendant 2: Erica van Herpen Date: 1 February 2015 Abstract Many studies have already examined the use of emotions in advertisements. However, these researches have only studied the influence of emotions in advertisements by investigating the valence and specific emotions, not which of these influences consumers the most. This study will research whether specific emotions influence people more than just random positive and negative emotions in advertisements. To answer the question: ‘With what framework can we predict emotion effects of advertisements on consumer behaviour?’ four emotions will be researched, namely; pride, happiness, fear, and guilt. The use of a specific framework, with advertisements with specific emotions in it, will be compared to the use of a valence framework, with advertisements with only positive and negative emotions in it, regardless of which emotions. The results of this research show that a specific framework predicts emotion effects the best. When an advertiser wants to use emotion appeals in his advertisement he should use an emotion, which appeals the most to his consumer segment. Further research should be done on the effects of different emotion appeals on consumer behaviour. If all emotion appeals that can possibly be used in advertisements are studied, it will become easier for marketers to use the most effective emotion appeals for their product in their advertisements. -

Textbook Pathos by Tim Jensen

Current Issue From the Editors Weblog Editorial Board Editorial Policy Submissions Archives Accessibility Search Composition Forum 34, Summer 2016 Textbook Pathos: Tracing a Through-Line of Emotion in Composition Textbooks Tim Jensen Abstract: Gretchen Flesher Moon’s 2003 analysis of emotion’s treatment in composition textbooks revealed that pathos "gets very short shrift" or none at all. Since then, however, conversations regarding affect and emotion have advanced in both scope and sophistication. This proliferation of scholarly activity has brought the passions of persuasion to a new level of prominence. This essay asks to what extent and in what ways these developments have manifested in representations of pathos in composition textbooks. In doing so, the article traces a through-line from Moon’s essay to now in order to provide a broader perspective of pathos in composition studies, and concludes with three recommendations for moving forward: 1) define emotion; 2) specify emotions; and 3) replace warnings and limits with complexity and curiosity. Of all the elements of classical rhetorical theory that have survived the attrition of history to influence current composition instruction, none have endured with the stamina and sweep of the Aristotelian appeals. If you are an undergraduate student taking a composition course, chances are high that you will encounter the rhetorical triptych of logos, ethos, and pathos. Chances are equally high that this encounter will initially take place through an assigned textbook reading, as the overwhelming majority of contemporary composition textbooks and rhetoric primers include mention of the three appeals in some fashion. In these texts, students are often prompted to identify various arguments’ use of appeals and then to label and analyze the moments in which an author or speaker is appealing specifically to their reason, for their trust, or to their emotions. -

THE SCRIBLERIAN Fall 2011 Edition

THE SCRIBLERIAN Fall 2011 Edition Sponsored by the English Department and the Braithwaite Writing Center, the Scriblerian is a publication for students by students. Revived during Fall Semester 2004 after a two-year hiatus, this on-line journal is the result of an essay competition organized by Writing Center tutors for ENGL 1010 and 2010 students. The Fall 2011 Scriblerian Contest was planned and supervised by Chair Blake London with the help of Jacqui Harrah, Vanessa Hunt, Dana LeCheminant, Violet Wager, and Wes Van de Water. A total of 26 essays were submitted for the Fall 2011 contest. 1 Contents Argumentative- English 1010 ........................................................................................................................ 2 1st Place Winner: Vincent Bundage II, “Game Design: Is it the End of a Knowledgeable and Social Society?” ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2nd Place Winner: Amber Overson, “Thin Is In, or Is It?” ...................................................................... 5 Expressive- English 1010 ............................................................................................................................. 10 1st Place Winner: Sherrin Rieff, “My Father’s Choice” ........................................................................ 10 2nd Place Winner: Megan Spence, “The Life of a Thread” .................................................................. 13 Argumentative- -

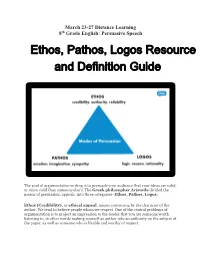

Ethos, Pathos, Logos Resource and Definition Guide

March 23-27 Distance Learning 8th Grade English: Persuasive Speech Ethos, Pathos, Logos Resource and Definition Guide The goal of argumentative writing is to persuade your audience that your ideas are valid, or more valid than someone else’s. The Greek philosopher Aristotle divided the means of persuasion, appeals, into three categories–Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Ethos (Credibility), or ethical appeal, means convincing by the character of the author. We tend to believe people whom we respect. One of the central problems of argumentation is to project an impression to the reader that you are someone worth listening to, in other words making yourself as author into an authority on the subject of the paper, as well as someone who is likable and worthy of respect. Pathos (Emotional) means persuading by appealing to the reader’s emotions. We can look at texts ranging from classic essays to contemporary advertisements to see how pathos, emotional appeals, are used to persuade. Language choice affects the audience’s emotional response, and emotional appeal can effectively be used to enhance an argument. Logos (Logical) means persuading by the use of reasoning. This will be the most important technique we will study, and Aristotle’s favorite. We’ll look at deductive and inductive reasoning, and discuss what makes an effective, persuasive reason to back up your claims. Giving reasons is the heart of argumentation, and cannot be emphasized enough. We’ll study the types of support you can use to substantiate your thesis, and look at some of the common logical fallacies, in order to avoid them in your writing. -

Critical Thinking in an Era of Partisanship

IPMA-HR: Critical Thinking in an Era of Partisanship September 24, 2018 Hector Zelaya Director, Bob Ramsey Executive Education College of Public Service & Community Solutions Creative vs Critical Thinking • Creative thinking involves a divergence of ideas. • Critical thinking involves a convergence of thought to distinguish between poor and good judgment. Gerras, “Thinking Critically about CriticalThinking: A Fundamental Guide for Strategic Leaders” Critical Thinking Concepts • Requires mental energy as opposed to heuristics (mental shortcuts) • Mental models – your understanding of how the world works • Cognitive biases – flawed mental models that influence decision making • Logical fallacies – faulty reasoning in a belief or argument A Critical Thinking Model Gerras, “Thinking Critically about CriticalThinking: A Fundamental Guide for Strategic Leaders” Key Elements of the Model • Concern vs Problem – Proactive vs reactive analysis • Point of view – how people see the world • Assumption – belief held to be true • Inference – conclusion something is true in light of something else being true or appearing to be true Gerras, “Thinking Critically about CriticalThinking: A Fundamental Guide for Strategic Leaders” Cognitive Biases • Confirmation: preference for ideas that are consistent with preconceptions • Fundamental attribution error – judging others on character but one’s self on situations • Self-serving: successes are due to the individual, and failures are due to external factors Adapted from https://yourbias.is/ Cognitive Biases -

Read Write Think

Persuasive Techniques in Advertising The persuasive strategies used by advertisers who want you to buy their product can be divided into three categories: pathos, logos, and ethos. Pathos: an appeal to emotion. An advertisement using pathos will attempt to evoke an emotional response in the consumer. Sometimes, it is a positive emotion such as happiness: an image of people enjoying themselves while drinking Pepsi. Other times, advertisers will use negative emotions such as pain: a person having back problems after buying the “wrong” mattress. Pathos can also include emotions such as fear and guilt: images of a starving child persuade you to send money. Logos: an appeal to logic or reason. An advertisement using logos will give you the evidence and statistics you need to fully understand what the product does. The logos of an advertisement will be the "straight facts" about the product: One glass of Florida orange juice contains 75% of your daily Vitamin C needs. Ethos: an appeal to credibility or character. An advertisement using ethos will try to convince you that the company is more reliable, honest, and credible; therefore, you should buy its product. Ethos often involves statistics from reliable experts, such as nine out of ten dentists agree that Crest is the better than any other brand or Americas dieters choose Lean Cuisine. Often, a celebrity endorses a product to lend it more credibility: Catherine Zeta-Jones makes us want to switch to T-Mobile. Practice labeling pathos, logos, and ethos by placing a P, L, or E in the blank : _____ A child is shown covered in bug bites after using an inferior bug spray.