Staging Poetic Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Ss8h7abcd SUMMARY - the New South – Racism – Civil Rights Activists of the Early 20Th Century

SS8H7abcd SUMMARY - The New South – Racism – Civil Rights Activists of the Early 20th Century SS8H7a Evaluate the impact the Bourbon Triumvirate, Henry Grady, International Cotton TOM WATSON and the POPULIST POLITICAL PARTY Exposition, Tom Watson and the Populists, Rebecca Latimer Felton, the 1906 Atlanta Riot, the Leo Frank Case, and the county unit system had on Georgia during this period. As a US Congressman and Senator from Georgia and leader of the Populists Political Party, Tom Watson helped support Georgia’s poor and struggling farmers. He created the RFD (Rural Free Delivery) which helped deliver US mail to people living in rural areas that helped build roads and bridges. Tom Watson opposed (was against) the New South movement and many of the conservative Democrat politicians. He believed that new industry in the South only helped people living in urban areas and did not benefit rural farmers. Early in his career Tom Watson tried to help both white AND black sharecroppers, but later in politics he became openly racist. COUNTY UNIT SYSTEM Elections were decided by a unit vote and not by a popular vote of the people. The population in each county determined how many unit votes a candidate would receive. There were 8 Urban counties that had the most population, but they only received six unit votes each. There were 30 Town counties that received four unit votes each. Finally, there were 121 Rural counties that received 2 unit votes each. This allowed small rural counties to have a lot of power in politics, however, the majority of the population of Georgia resided in Urban and Town counties. -

The South Vs Leo Frank

Kentucky Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 3 May 2017 The outhS vs Leo Frank: Effects of Southern Culture on the Leo Frank Case 1913-1915 Kellye Cole Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/kjus Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Cole, Kellye (2017) "The outhS vs Leo Frank: Effects of Southern Culture on the Leo Frank Case 1913-1915," Kentucky Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://encompass.eku.edu/kjus/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship by an authorized editor of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRISM: A Journal of Regional Engagement The South vs Leo Frank: Effects of Southern Culture on the Leo Frank Case 1913-1915 Kellye Cole Carolyn Dupont, PhD Eastern Kentucky Eastern Kentucky University University Abstract: In 1915, a young man from New York became the only Jewish person ever lynched in America. This paper analyzes primary and secondary sources including newspapers, magazines and personal accounts to consider the events that led to Leo Frank’s death in Georgia. Anti-Semitism, populism, racism, and newspaper coverage all infected the case. Despite extensive analysis in historical and popular works, the culture of Southern honor has typically been relegated to a minor role in the case. This study challenges the widely held assumption that anti-Semitism was the main impetus for the lynching and instead focuses on the culture of Southern honor as the ultimate cause. -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Student Guide Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS APRIL 13 - JUNE 21, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team........................................................................................................................................................................8 Presents for Mrs. Rogers......................................................................................................................................................................9 Will Rogers..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 Wiley Post, Aviation Marvel..............................................................................................................................................................16 -

T Wentieth Centur Y North Amer Ican Drama

TWENTIETH CENTURY NORTH AMERICAN DRAMA, SECOND EDITION learn more at at learn more alexanderstreet.com Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition contains 1,900 plays from the United States and Canada. In addition to providing a comprehensive full-text resource for students in the performing arts, the collection offers a unique window into the econom- ic, historical, social, and political psyche of two countries. Scholars and students who use the database will have a new way to study the signal events of the twentieth century – including the Depression, the role of women, the Cold War, and more – through the plays and performances of writers who lived through these decades. More than 1,250 of the works are in copyright and licensed Jules Feiffer, Neil LaBute, Moisés Kaufman, Lee Breuer, Richard from the authors or their estates, and 1,700 plays appear in Foreman, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Horton Foote, Romulus Linney, no other Alexander Street collection. At least 550 of the works David Mamet, Craig Wright, Kenneth Lonergan, David Ives, Tina have never been published before, in any format, and are Howe, Lanford Wilson, Spalding Gray, Anna Deavere Smith, Don available only in Twentieth Century North American Drama, DeLillo, David Rabe, Theresa Rebeck, David Henry Hwang, and Second Edition – including unpublished plays by major writers Maria Irene Fornes. and Pulitzer Prize winners. Besides the mainstream works, users will find a number of plays Important works prior to 1920 are included, with the concentration of particular social significance, such as the “people’s theatre” of works beginning with playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill, exemplified in performances by The Living Theatre and The Open Elmer Rice, Sophie Treadwell, and Susan Glaspell in the 1920s Theatre. -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

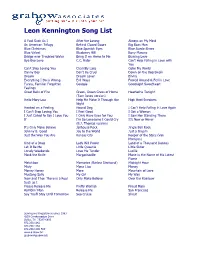

Leon Kennington Song List

Leon Kennington Song List A Fool Such As I After the Loving Always on My Mind An American Trilogy Behind Closed Doors Big Boss Man Blue Christmas Blue Spanish Eyes Blue Suede Shoes Blue Velvet Blueberry Hill Bony Marony Bridge over Troubled Water Bring It on Home to Me Burning Love Bye Bye Love C.C. Rider Can’t Help Falling in Love with You Can’t Stop Loving You Chantilly Lace Color My World Danny Boy Don’t Be Cruel Down on the Boardwalk Dream Dream Lover Elivira Everything I Do is Wrong Evil Ways Fooled Around & Fell in Love Funny, Familiar Forgotten Georgia Goodnight Sweetheart Feelings Great Balls of Fire Green, Green Grass of Home Heartache Tonight (Tom Jones version) Hello Mary Lou Help Me Make It Through the High Heel Sneakers Night Hooked on a Feeling Hound Dog I Can’t Help Falling in Love Again I Can’t Stop Loving You I Feel Good I Got a Woman I Just Called to Say I Love You I Only Have Eyes for You I Saw Her Standing There If I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry It’s Now or Never (B.J. Thomas version) It’s Only Make Believe Jailhouse Rock Jingle Bell Rock Johnny B. Good Joy to the World Just a Dream Just the Way You Are Kansas City Keeper of the Stars (Van Morrison) Kind of a Drag Lady Will Power Land of a Thousand Dances Let It Be Me Little Queenie Little Sister Lonely Weekends Love Me Tender Lucille Mack the Knife Margaritaville Marie in the Name of His Latest Flame Matchbox Memories (Barbra Streisand) Midnight Hour Misty Mona Lisa Money Money Honey More Mountain of Love Mustang Sally My Girl My Way Now and Then There is a Fool Only -

The Playwright As Filmmaker: History, Theory and Practice, Summary of a Completed Thesis by Portfolio OTHNIEL SMITH, University of Glamorgan

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol 1, No 2 (2007) ARTICLE The Playwright as Filmmaker: History, Theory and Practice, Summary of a completed thesis by portfolio OTHNIEL SMITH, University of Glamorgan ABSTRACT This paper summarises my doctoral research into the work of dramatists who became filmmakers – specifically Preston Sturges, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, David Mamet, and Neil Labute. I began with the hypothesis that there is something distinctive about the work of filmmakers who have a background in writing for text-based theatre, an arena where the authorship is, on the whole, not a vexatious issue, as is the case in commercial cinema. Through case studies involving textual and contextual analyses of their films, I found common threads linking their work, in respect both of their working methods and their approach to text and performance. From this, I evolved a theoretical position involving the development of a tentative ‘dogme’ designed to smooth the path between writing plays and making films, and produced short no- budget videos illustrating it. KEYWORDS Theatre/film, Dogme, theoretical practice, Mamet, Fassbinder. Introduction The aim of this project – a thesis by portfolio, completed at the now-defunct Film Academy at the University of Glamorgan – was to contribute to that area within film theory where creativity is taken seriously as a field of study; an attempt to reconcile theory with artistry, without attempting to theorise artistry. The ‘theatrical’ is often characterised as the ‘other’ of the cinematic, within both popular and scholarly discourse. My intention was to examines the interface between the two forms, and isolate those aspects of the theatrical aesthetic which can be profitably employed within cinema, looking at the issue from the perspective of the working dramatist – my background being as a writer for theatre, radio and television. -

Parade Diverges: the 1998 Broadway and 2007 London Productions and Their Critical Receptions Julie L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Parade Diverges: The 1998 Broadway and 2007 London Productions and Their Critical Receptions Julie L. Haverkate Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE PARADE DIVERGES: THE 1998 BROADWAY AND 2007 LONDON PRODUCTIONS AND THEIR CRITICAL RECEPTIONS By JULIE L. HAVERKATE A Thesis submitted the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 Copyright © 2008 Julie L. Haverkate All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Julie L. Haverkate defended on 19 March 2008. ______________________________ Natalya Baldyga Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member ______________________________ Tom Ossowski Committee Member ______________________________ Fred Chappel Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Much of thesis would not have been possible without the support of Jason Robert Brown. For his infinite patience with my constant barrage of emails and questions, his willingness to meet with me, and his candid discussion of his own work, I offer my warmest and most sincere thanks. Beyond even that, and most importantly, I genuinely thank him for his continuing contributions