Norris, Keith: Transcript of an Audio Interview (15-Dec-2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Historiography of Molecular Biology

Reflections on the Historiography of Molecular Biology HORACE FREELAND JUDSON SURELY the time has come to stop applying the word revolution to the rise of new scientific research programmes. Our century has seen many upheavals in scientific ideas--so many and so varied that the notion of scientific revolution has been stretched out of shape and can no longer be made to cover the processes of change characteristic of most sciences these past hundred years. By general consent, two great research pro- grammes arising in this century stand om from the others. The first, of course, was the one in physics that began at the turn of the century with quantum theory and relativity and ran through the working out, by about 1930, of quantum mechanics in its relativistic form. The trans- formation in physics appears to be thoroughly documented. Memoirs and biographies of the physicists have been written. Interviewswith survivors have been recorded and transcribed. The history has been told at every level of detail and difficulty. The second great programme is the one in biology that had its origins in the mid-1930s and that by 1970 had reached, if not a conclusion, a kind of cadence--a pause to regroup. This is the transformation that created molecular biology and latter-day biochemistry. The writing of its history has only recently started and is beset with problems. Accounting for the rise of molecular biology began with brief, partial, fugitive essays by participants. Biographies have been written of two, of the less understood figures in the science, who died even as the field was ripening, Oswald Avery and Rosalind Franklin; other scientists have wri:tten their memoirs. -

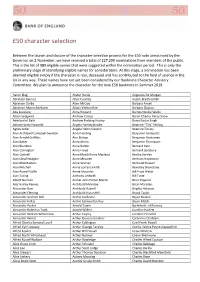

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

Universities and Colleges Than in August 1952

DEC. 26, 1953 MEDICAL NOTES IN PARLIAMENT IBRiTiSH 1437 MEDICAL JOURN~AL since the National Health Service started, I am glad to say that in August the estimated cost fell to about lid. less Universities and Colleges than in August 1952. This was maintained in September and there was a further reduction to 2d. in October. I am glad to have this opportunity to thank the joint committee UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM on prescribing for their valuable work in classifying prepar- Dr. H. F. Humphreys has been appointed a governor of the Uni- versity College of North Staffordshire for three years. ations, and the General Medical Services Committee of the Enid Charles, Ph.D., Reader in Demography and Vital British Medical Association and the whole body of general Statistics in the University, has accepted an invitation from the practitioners for their co-operation in producing this World Health Organization to advise the University of Malaya encouraging result. on the setting up of a department of demography and medical Mr. LONGDEN asked whether this satisfactory result fol- statistics, and has been granted leave of absence for one year lowed on the advice given to general practitioners about from August 1, 1953. prescribing drugs of doubtful therapeutic value. Mr. Dr. W. T. Cooke, Reader and First Assistant in Medicine, has been granted leave of absence for the first quarter of 1954 MACLEOD said it seemed almost certain that the two were to visit gastro-intestinal and metabolic clinics in the U.S.A. linked, because the letter was sent out by the Chief Medical The Rockefeller Foundation has made a grant of £28,800 to Officer on July 18 and the first noticeable drop was in the Professor J. -

Chinatown Was Made up of One Stretch Along Empire Street

THE CENTRAL KINGDOM, CONTINUED GO BACK TO THE PREVIOUS PERIOD 1900 It was after foreign soldiers had gunned down hundreds of Chinese (not before, as was reported), that a surge of Boxers laid siege to the foreign legations in Peking (Beijing). A letter from British Methodist missionary Frederick Brown was printed in the New-York Christian Advocate, reporting that his district around Tientsin was being overrun by Boxers. The German Minister to Beijing and at least 231 other foreign civilians, mostly missionaries, lost their lives. An 8-nation expeditionary force lifted the siege. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY When the Chinese military bombarded the Russians across the Amur River, the Russian military responded by herding thousands of members of the local Chinese population to their deaths in that river. Surprise, the Russians didn’t really want the Chinese around. At about the turn of the century the area of downtown Providence, Rhode Island available to its Chinese population was being narrowed down, by urban renewal projects, to the point that all of Chinatown was made up of one stretch along Empire Street. Surprise, the white people didn’t really want the Chinese around. In this year or the following one, the Quaker schoolhouse near Princeton, New Jersey, virtually abandoned and a ruin, would be torn down. The land on which it stood is now the parking lot of the new school. An American company, Quaker Oats, had obtained hoardings in the vicinity of the white cliffs of Dover, England, for purposes of advertising use. -

Holding Hands with Bacteria the Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN MOLECULAR SCIENCE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 123 SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science History of Chemistry Series editor Seth C. Rasmussen, Fargo, North Dakota, USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10127 Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 1 3 Soňa Štrbáňová Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Prague Czech Republic ISSN 2191-5407 ISSN 2191-5415 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science ISSN 2212-991X SpringerBriefs in History of Chemistry ISBN 978-3-662-49734-0 ISBN 978-3-662-49736-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-49736-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934952 © The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Lovsin, Robert D..Pdf

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Non-Conventional Armament Linkages: Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Weapons in the United Kingdom and Iraq Robert D. Lovsin Doctor of Philosophy Science & Technology Policy University of Sussex December 2010 I hereby declare that this dissertation has not been, and will not be, submitted to this or any other university for the award of any other degree. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the reasons why states want to acquire non- conventional weapons and analyzes interconnections between decisions on nuclear weapons (NW) on the one hand and chemical/biological weapons (CBW) on the other. Much of the literature on non-conventional weapons has tended to focus either on nuclear weapons or on CBW, with CBW often portrayed as the “poor man’s nuclear bomb.” While there is some truth in this, the interconnections between decisions to develop NW and decisions to develop CBW are more numerous, more varied and more nuanced. The dissertation examines non-conventional armament processes in the United Kingdom and Iraq. -

Focus on Virology Ritchie's Microscope Slides Discovered Interview with Jeff Almond a New Era of Genome Engineering

Fusion 13 2014 24pp_Layout 1 22/09/2014 12:11 Page 1 fusionTHE NEWSLETTER OF THE SIR WILLIAM DUNN SCHOOL OF PATHOLOGY ISSUE 13 . MICHAELMAS 2014 Interview with Jeff Almond Focus on Virology A New Era of Genome Engineering Ritchie’s Microscope Slides Discovered Fusion 13 2014 24pp_Layout 1 22/09/2014 12:18 Page 2 2 / FUSION . OCTOBER 2014 Editorial Contents Having completed my first full academic year at the Dunn School, it is Editorial perhaps a good time to take stock. It has been a steep learning curve Matthew Freeman .........................................2 and I am certainly not yet at the top; nevertheless, I know a lot more about how Oxford works, we have filled a floor of OMPI with young and News: The Dunn School honoured in the exciting group leaders and we have negotiated the external processes Bodleian Library’s exhibition of Great of our REF submission and Athena SWAN accreditation. We have also Medical Discoveries......................................3 had a couple of great parties. CAMPATH approved by NICE for use in The most long hours. It is also a fact of life that not the treatment of multiple sclerosis......3 interesting and everyone who embarks on the journey will reach Research Focus: important aspect of their expected destination. It is, therefore, Keeping the centrosome under control. my role as Head of essential that we design processes to support Zsofia Novak ....................................................4 Department is people as they progress and reach important Rad51: An essential recombinase and recruitment of decision points. The Dunn School has a tradition of beyond. Fumiko Eshashi..................................6 group leaders. -

COVID-19 People, Etc

COVID-19: People, Places, Concepts, Science Copyright Notice: This material was written and published in Wales by Derek J. Smith (Chartered Engineer). It forms part of a multifile e-learning resource, and subject only to acknowledging Derek J. Smith's rights under international copyright law to be identified as author may be freely downloaded and printed off in single complete copies solely for the purposes of private study and/or review. Commercial exploitation rights are reserved. The remote hyperlinks have been selected for the academic appropriacy of their contents; they were free of offensive and litigious content when selected, and will be periodically checked to have remained so. Copyright © 2020, Derek J. Smith. First published 26th March 2020. This version 09:00 GMT 30th November 2020 [BUT UNDER CONSTANT EXTENSION AND CORRECTION, SO CHECK AGAIN SOON] Author's Home Page and e-mail Address >>>>> Also available ... <<<<< COVID, Day by Day COVID, the hard science Albizu Campos, Pedro: Puerto Rican independence leader Pedro Albizu Campos [Wikipedia biography] is noteworthy in the present context for sharing the spotlight of history 1932-1937 with America's own Doctor Mengele, Cornelius ["Dusty"] Rhoads - for the details, see that entry. Anyang Research Station: See the entry for Junji Nakamura. Army Technical Research Unit #9: See the entry for Noboru Kuba. "Arnold"CODENAME: See the entry for Hermann Wuppermann. Ashford, Bailey Kelly: American military physician [Colonel] Bailey K. Ashford [Wikipedia biography] is noteworthy in the present context (a) for an early career ministering to the American invasion force in Puerto Rico [see Aneurin Timeline 25th July 1898], becoming by the end of 1899 a specialist voice in the management of the locally endemic "tropical chlorosis", that is to say, hookworm-vectored anaemia [Wikipedia briefing], nicely profiled in Daniel Immerwahr's (2019) book "How to Hide an Empire" [Amazon] as follows .. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS Table of Contents

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Table of Contents Schedule 2 Program 3 Sunday July 5 3 Monday July 6 5 Tuesday July 7 81 Wednesday July 8 169 Thursday July 9 229 Friday July 10 295 Index 328 ISHPSSB PROGRAM P | 3 Schedule SUNDAY JULY 5 LOBBY OF J.-A.-DESÈVE (DS) BUILDING SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 13:00 – 17:00 REGISTRATION JULY 5 JULY 6 JULY 7 JULY 8 JULY 9 JULY 10 8H00 > Registration 9H00 > MARIE-GÉRIN-LAJOIE AUDITORIUM 17:00 – 18:00 Session 1 Session 4 Session 8 Session 11 Session 14 PRESIDENT’S WELCOME 10H00 > COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK 11H00 > MARIE-GÉRIN-LAJOIE AUDITORIUM Session 2 Session 5 Session 9 Session 12 Session 15 18:00 – 20:00 12H00 > WELCOME TO MONTRÉAL COCKTAIL LUNCH BREAK LUNCH BREAK LUNCH BREAK LUNCH BREAK LUNCH BREAK 13H00 > Grad. student Early career scholar general meeting Council Council Council 14H00 mentoring lunch > meeting meeting meeting Membership diversity meeting 15H00 > Registration 16H00 > Session 3 Session 6 Session 10 Session 13 17H00 > Excursions in President’s COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK COFFEE BREAK and around Montreal welcome 18H00 > Awards ceremony Plenary session Session 7 Plenary session and ISHPSSB Sandra Harding W. Ford Doolitlle Welcome general meeting 19H00 > to Montréal cocktail Pub night cocktail Poster session and Montréal best 20H00 > and cocktail poster prize Dining buffet (“ Cocktail dînatoire ”) 21H00 > 22H00 > NOTE: the symbol ** indicates that, at time of publication, the attendance of this presenter has not been confirmed. INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY, PHILOSOPHY, AND SOCIAL STUDIES OF BIOLOGY ISHPSSB PROGRAM P | 5 MONDAY JULY 6 LOBBY OF J.-A.-DESÈVE (DS) BUILDING 08:00 – 09:00 REGISTRATION INDIVIDUAL PAPERS DS 1420 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES: INTERDISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVES 09:00 – 10:30 Evolution and (Aristotelian) virtue ethics JOHN MIZZONI (Neumann University, United States) It is well known that virtue ethics has become very popular among moral theorists. -

Appendix 1 Organization of Advice on Biological Warfare (1947)

Appendix 1 Organization of Advice on Biological Warfare (1947) 188 Outline Chronology 1925 Geneva Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Gas and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare 1934 July Wickham Steed publishes allegations of German biological warfare testing on London Underground and Paris Metro. Ledingham, Douglas and Topley write a secret report on the Wickham Steed allegations for the Committee of Imperial Defence 1936 November Committee of Imperial Defence Subcommittee on Bacteriological Warfare. First meeting 1937 April Committee of Imperial Defence Subcommittee on Bacteriological Warfare proposes Emergency Public Health Service. Eventually becomes Public Health Laboratory Service 1938 May Subcommittee on Bacteriological Warfare renamed Subcommittee on Emergency Bacteriological Services August Subcommittee on Emergency Bacteriological Services becomes Committee on Emergency Public Health Laboratory Services 1939 September Start of Second World War: Germany invades Poland Sept.–Feb. Prime Minister Chamberlain approves of defensive research (1940) to be undertaken on biological warfare at National Institute of Medical Research November War Cabinet establishes BW Committee 1940 February War Cabinet BW Committee. First meeting. Considers Banting’s memorandum proposing offensive biological warfare research. Hankey invites Ledingham to draw up a research plan with no intention of taking offensive measures but which was not to exclude offensive research which might improve defence May Churchill becomes Prime Minister July Hankey proposes his ‘step further’ to expand the biological warfare research programme without consulting War Cabinet November Fildes arrives at new Biology Department Porton 1942 January Cabinet Defence Committee affirms policy to undertake research in order to be able to retaliate without undue delay with biological weapons July, Sept. -

Chapter 33 BOTULINUM TOXINS

Botulinum Toxins Chapter 33 BOTULINUM TOXINS JOHN L. MIDDLEBROOK, PH.D.*; AND DAVID R. FRANZ, D.V.M., PH.D.† INTRODUCTION HISTORY AND MILITARY SIGNIFICANCE DESCRIPTION OF THE AGENT Serology Genetics PATHOGENESIS Relation to Other Bacterial Toxins Stages of Toxicity CLINICAL DISEASE DIAGNOSIS MEDICAL MANAGEMENT SUMMARY *Chief, Life Sciences Division, West Desert Test Center, Dugway Proving Ground, Dugway, Utah 84022; formerly, Scientific Advisor, Toxinology Division, U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, Frederick, Maryland 21702-5011 †Colonel, Veterinary Corps, U.S. Army; Commander, U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, Frederick, Maryland 21702-5011 643 Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare INTRODUCTION The clostridial neurotoxins are the most toxic sub- immunization of the general population is not war- stances known to science. The neurotoxin produced ranted on the basis of cost and the expected rates from Clostridium tetani (tetanus toxin) is encountered of adverse reactions to even the best vaccines. by humans as a result of wounds and remains a seri- Thus, humans are not protected from botulinum ous public health problem in developing countries toxins and, because of their relative ease of produc- around the world. However, nearly everyone reared tion and other characteristics, these toxins are likely in the western world is protected from tetanus toxin biological warfare agents. Indeed, the United States as a result of the ordinary course of childhood immu- itself explored the possibility of weaponizing botu- nizations. Humans are usually exposed to the neuro- linum toxin after World War II, as is discussed else- toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum (ie, the botu- where in this textbook. -

£50 Character Selection of Names

£50 character selection Since the Governor launched the character selection process for the £50 note on 2 November, we have received a total of 174,112 nominations. This is the list of eligible names that were nominated in the first week (covering the first 114,000 nominations). This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: at this first stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We encourage the public to continue nominating characters until 14 December at www.bankofengland.co.uk/thinkscience. We will release the list of all eligible nominations once the window closes. More details on the character selection process can be found here: www.bankofengland.co.uk/thinkscience. Abraham Darby Anita Harding Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Abraham Manie Adelstein Ann Bishop Beatrice de Cardi Ada Lovelace Ann McNeill Beatrice Tinsley Agnes Arber Anna Atkin Benjamin Huntsman Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anna Bidder Benjamin Thompson Alan Arnold Griffiths Anna Freud Bernard Lovell Alan Baker Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bernard Spilsbury Alan Blumlein Anne McLaren Bertha Swirles Alan F Mitchell Anne Warner Bertram Hopkinson Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Annie Lorrain Smith Bertrand Russell Alan Powell Goffe Annie Maunder Bill Frost Welsh Alan Turing Anthony Ledwith Bill Penney Alec Reeves Archibald McIndoe Bill Tutte Alexander Fleming