February, 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

MUSICAL NOTES. Orchestra, at Long Beach, Are Deservedly Praised

THE MUSICAL CRITIC AND TRADE REVIEW. September 5th, 1880 SCHREINER.—Mr. Kleophas Schreiner's Military Band and String MUSICAL NOTES. Orchestra, at Long Beach, are deservedly praised. There is a great deal of strength and precision in the performances, and Mr. Schreiner has a good AT HOME. and varied repertoire. Some of the soloists are excellent. Mr. Hoch is ap- DODWORTH.—Harvey B. Dodworth was engaged to furnish the music plauded after his cornet performances, and Mr. Neubech, the concert master for the Rockaway Beach Improvement Company at the big hotel; but as the of the orchestra, has made many friends by an artistic rendering of Max hotel -was not finished, he was forced to remain idle seven weeks. He now Bruch's first Concerto for the Violin. has a claim against the company for $10,080. THAYER.—The Kate Thayer Concert Company, under the management MARETZEK.—Max Maretzek has accepted the position of "Professor of of Mr. Will E. Chapman, will enter upon a concert tournee on October 17. the School for Operatic Training," in the College of Music of Cincinnati, The company comprises Miss Kate Thayer, Miss Maurer, pianist, the Spanish and "will enter upon his duties about the middle of this month. Students, and some other artistes. Whether the company will appear in New York during the season, we do not know, as the dates of the entire- STEBNBERG.—Heir Constantin Sternberg, a Russian piano virtuoso, season have not been settled upon yet. has been engaged for 100 concerts in America. He will arrive in New York in September. -

Rockland Gazette : October 14, 1880

'he Rockland Gazette. Gazette Job Print I PUBLISHED f.\ERY THURSDAY AFTERNOON bY ESTABLISHMENT. Having every facility in Presses, Type and Material O SE & PORTER. — which we are constantly making additions, w« piepared tv execute with promptness and good 2 I O Matin S treet. every variety of Job Printing, Including Town Reports, Catalogues, By-La^ft* Posters, Shop Bills, Hand Bills, Pro T E R 3*1 H i r paid strictly in advance—l>er«nnum, $2.00. grammes, Circulars, Bill Heads, if payment is delayed o months, 2.26. Letter Heads, Law and Corpor 2.60. t paid till the close of the year, ation Blanks, Receipts, Bills few subscribe! a are expected to make the first of Lading, Business, Ad went in advance. “ dress and Wedding “Ko paper will be diacontlnu^*^ Cards, Tags, ire paid, unless at the option ofv^.he pubiish- Labels, ____ - Single copies five cents—for sale at tliec® cean*i ROCKLAND, MAINE, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 14, 1880. &c., j at the Bookstores. V O L U M E 3 5 . N O . 4 6 . PRINTING IN COLORS AND BRONZINO ’ &. POPE VO8E. J- B. PORTER- will receive prompt attention. were stopped, the wounded member ex left after everything was settled to finish A WEDDING IN CAIRO. desirable acquisitions. The eunuchs vainly [From our Regular Correspondent. M r ® . tracted, hut all bruised and bleeding. the hoy’s education, and the dear, brave endeavor to maintain order, and are nt no Our European Letter. harden f g f lm r . Eleanor’s fingers bound up tho lacerated girl would not let them tell tho young fel A Graphic Picture of the Ceremony iu an pains to enforce their wishes with modera hand in her own small handkerohief, the low how much it was. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Vol. 4. Contents. No.2

Price, Its Cents. 53.76 Worth of MUSIC in This Number. Vol. 4. No.2. Contents. GENERAL ..........•......................... , ...• page 55 What Care I? (Poetry).-Comical Chords. EDITORIAL ...................................... page 56 Paragraphs.-The People's l\fusical Taste. l\fUSICAL ................ ........................ page 66 Piano Recitals at the St. Louis Fair. l\1ISCELLANEOUS ......... .. ..................... page 58 The Musician to His Love (Poetry) .-Major and Mmor. -Love and Sorrow (Poetry).-New York.-Pleyel. -Anecdote of Beethoven.-Donizetti's Piano -Forte. -l\fnsic and IUedicine.-Answers to Correspondents. -What the PTess Think of lt.-Smith and Jones. MUSIC IN THIS NUMBER. " Careless Elegance," Geo. Schleiffarth ......... page fi7 "Peep o' Day Waltz," Alfred von Rochow ...... page 70 " The Banjo," Claude Melnotte .........•........ page 72 " Greetings of Love" (Duet), Wm. Siebert ...... page 74 ~· 'l'hou'rt Like Unto a Flower," A. Rubinstein ... page 78 "Because 1 Do," J. L. Molloy .................... page 80 "Goldbeck's Harmony" .........................._ page Si KUNKEL BROS., Publishers, ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI. COPYRIGHT, KUNKEL BROS., 1S8l. 50 KUNKEL'S MUSICAL REVIEW, OCTOBER, 1881. "USED BY ALL THE GREAT ARTISTS" THE AJR'll'JI§'Jf§. AR'lfli§'Jf§, LIEBLING, HE~RY F. MILLE~ PI) NOS SHERWOOD, PERRY, PRESTON, ARE PRONOUNCED THE BEST HENRIETTA MAURER, BY '£HE MRS. SHERWOOD, HOFFMAN, Leadin Artists of the Present Time, PEASE, AND ARE USED Bl' THEM CHARLES R. ADAMS, P. BIUGNOLI, IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE. CLARA LOUlSE KET"LOGG, ANNIE LOUISE CARY, EMMA TIIURSRY, These celebrated instruments arc the favorites, at1d are MARIE ROZE, used in the finest concerts in the principal cities of TOll! KARL, i\mericn. W. II. l<'ESSENDEN, The characteristir.s which have given these Pianos their l\1. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

INFANTRY HALL PROVIDENCE >©§to! Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER ii^^i^"""" u Yes, Ifs a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extr? dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere 2>ympif Thirty-fifth Season,Se 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUC per; \l iCs\l\-A Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet, H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Stilzen, H. Fiedler, A. -

April 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 04 (April 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 04 (April 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/568 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO PIANOS THE ETUDE FOUR HANDS New Publications The following ensemble pieces in- S^s?^yssL*aa.‘Sffi- Anthems of Prayer and Life Stories of Great nai editions, and some of the latest UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS Sacred Duets novelties are inueamong to addthe WOnumberrks of For All Voices &nd General Use Praise Composers OF STANDARD QUALITY A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. sis Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE Subscription Price, $1.60 per jeer In United States Alaska, Cuba, Po Mexico, Hawaii, Pb’”—1— "-“-“* *k- "•* 5 In Canada, »1.7t STYLISH PARASOLS FOUR DISTINCT ADVANCE STYLES REMITTANCES should be made by post-offlee t No. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ew riter face, while others may be fi’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improperalig n m ent can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9420996 Music in the black and white conununities in Petersburg, Virginia, 1865—1900 Norris, Ethel Maureen, Ph.D. -

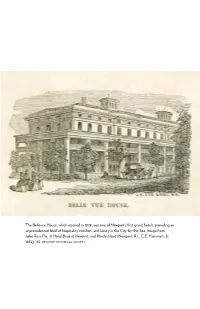

The Bellevue House, Which Opened in 1828, Was One of Newport's First

The Bellevue House, which opened in 1828, was one of Newport’s first grand hotels, providing an unprecedented level of hospitality, comfort, and luxury in the City-by-the-Sea. Image from John Ross Dix. A Hand-Book of Newport, and Rhode Island (Newport, R.I.: C.E. Hammett, Jr, 1852), 157. NEWPORT HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Music and Dancing at the “Queen of Resorts”: The Impact of the Germania Musical Society on Newport’s Hotel Period Brian M. Knoth We have the most absolute faith in steam factories, but we do not wish to see any more built in Newport…Let not the hum of spindles mock the music of the Sea .1 Music and dancing were integral features of Newport’s revival as a popular resort destination during its hotel period that began in the 1840s . Following a long period of economic depression, this era marked Newport’s emergence as a premier watering hole, with the establishment of several large well-appointed seaside hotels . At its height, in the 1850s, Newport was a world-class summer destination, known as the “Queen of Resorts ”. An extraordinary group of German musicians called the Germania Musical Society were instrumental to Newport’s flourishing resort economy during the 1850s . The significance of the Germania on Newport’s summer society, music culture, and resort traditions during the 1850s cannot be overstated . The Germania Musical Society first played in Newport in 1849, and for much of the next decade brought unrivaled musical experiences to Newport summer audiences for the first time, complementing a stunning natural environment and luxurious accommodations . -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 18, 1898

^5^5 BOSTON SYMPHONY OROIESTRK fcs season PRSGRHttrtE |l4J : New Scale, Style AA Believing that there is always demand for the highest possible degree of excellence in a given manufacture, the Mason & Hamlin Company has held steadfast to its original principle, and has never swerved from its purpose of producing instruments of rare artistic merit. As a result the Mason & Hamlin Company has received for its products, since its foundation to the present day, words of greatest commendation from the world's most illustrious musicians and critics of tone. Since and including the Great World's Exposition of Paris, \ 867, the instruments manufactured by the Mason & Hamlin Company have received, wherever exhibited, at all great world's expositions, the HIGHEST POSSIBLE AWARDS. SEND FOR CATALOGUE. mm & ipilm €0. BOSTON. NEW YORK. CHICAGO. Retail Representatives X^m^y 146 BOYLSTON STREET, BOSTON. Boston Symphony Orchestra. MUSIC HALL, BOSTON. EIGHTEENTH SEASON, J> J> J> 1893-99. J> J> J> WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor, r*j*ooi*iV]M:]V£K^ OF THE * FOURTEENTH REHEARSAL and CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY WILLIAM F. APTHORP.^** FRIDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 3, AT 2.30 O'CLOCK. SATURDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 4. AT 8.00 O'CLOCK. PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER. (489) Steinway & Sons, /lanufacturers Grand and ! \ j^T £ \ ^L of PIANOS/\1^\J^ Upright Beg to announce that they have been officially appointed by patents and diplomas, which are displayed for public inspection at their warerooms, manufacturers to His riajesty, NICOLAS II., THE CZAR OF RUSSIA. His Majesty, WILLIAM II., EMPEROR OF GERMANY and THE ROYAL COURT OF PRUSSIA. -

Music (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library)

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Watkinson Library (Rare books & Special Watkinson Publications Collections) 2016 American Periodicals: Music (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library) Leonard Banco Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/exhibitions Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Banco, Leonard, "American Periodicals: Music (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library)" (2016). Watkinson Publications. 22. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/exhibitions/22 Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library • • • • American Perioclicals: USIC Series Introduction A traditional focus of collecting in the Watkinson since we opened on August 28, 1866, has been American periodicals, and we have quite a good representation of them from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries. However, in terms of "discoverability" (to use the current term), it is not enough to represent each of the 600-plus titles in the online catalog. We hope that our students, faculty, and other researchers will appreciate this series ofannotated guides to our periodicals, broken down into basic themes (politics, music, science and medicine, children, education, women, etc.), MUSIC all of which have been compiled by Watkinson Trustee and Introduction volunteer Dr. Leonard Banco. We extend our deep thanks to Len for the hundreds of hours he has devoted to this project The library holds a relatively small but significant since the spring of 2014. His breadth of knowledge about the collection of19 periodicals focusing on music that period and inquisitive nature has made it possible for us to reflects the breadth ofmusical life in 19th-century promote a unique resource through this work, which has America as it transitioned from an agrarian to an already been of great use to visiting scholars and Trinity industrial society. -

559700 Bk Hanson US

Robert SCHUMANN Arrangements for Piano Duet • 1 String Quartet in A major Piano Quintet in E flat major Eckerle Piano Duo Robert Schumann (1810-1856) complete score, indispensable for the study and son of a wine merchant, he emigrated in 1848 to America, Arrangements for Piano Duet • 1 dissemination of these works. It was then a normal played a decisive rôle in Boston musical life from 1852 process to think of creating the traditional duet onwards and died in Beverly near Boston on 26th July In an age before sound recording was possible, made under his supervision, as well as a representative arrangement. In the middle of 1848, Otto Dresel, at the 1890. He came back several times to Europe and also arrangements for, initially, solo piano offered the only way choice of other orchestral works and important chamber time 21 years old, who, as a graduate of the Leipzig won great recognition for his arrangements of works by to get to know, play and hear works for larger music music pieces for which musically significant and aurally Conservatory knew and admired Mendelssohn and Bach, Handel and Beethoven, as well as for English groups, for example for orchestra with or without voices convincing arrangements were published, sometimes Schumann, sent his piano duet arrangement of the three translations of the Lieder of his friend Robert Franz. and also for works not yet available for such instruments after Schumann’s death. quartets to the publishers Breitkopf & Härtel who, as the organ. From the early years of the 19th century, as however, first wanted to obtain the authorisation of the Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op.