PERSECUTION of MUSLIMS in BURMA BHRN Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Islamophobia and Religious Intolerance: Threats to Global Peace and Harmonious Co-Existence

Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies (QIJIS) Volume 8, Number 2, 2020 DOI : 10.21043/qijis.v8i2.6811 ISLAMOPHOBIA AND RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE: THREATS TO GLOBAL PEACE AND HARMONIOUS CO-EXISTENCE Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), Jabi-Abuja, Nigeria Consultant, FARKAZ Technologies & Education Consulting Int’l, Ijebu-Ode [email protected] Abstract Recent events show that there are heightened fear, hostilities, prejudices and discriminations associated with religion in virtually every part of the world. It becomes almost impossible to watch news daily without scenes of religious intolerance and violence with dire consequences for societal peace. This paper examines the trends, causes and implications of Islamophobia and religious intolerance for global peace and harmonious co-existence. It relies on content analysis of secondary sources of data. It notes that fear and hatred associated with Islām and persecution of Muslims is the fallout of religious intolerance as reflected in most melee and growingverbal attacks, trends anti-Muslim of far-right hatred,or right-wing racism, extremists xenophobia,. It revealsanti-Sharī’ah that Islamophobia policies, high-profile and religious terrorist intolerance attacks, have and loss of lives, wanton destruction of property, violation led to proliferation of attacks on Muslims, incessant of Muslims’ fundamental rights and freedom, rising fear of insecurity, and distrust between Muslims and QIJIS, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2020 257 Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA The paper concludes that escalating Islamophobic attacks and religious intolerance globally hadnon-Muslims. constituted a serious threat to world peace and harmonious co-existence. Relevant resolutions in curbing rising trends of Islamophobia and religious intolerance are suggested. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Inquiry Into the Status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion Or Belief

Inquiry into the status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief Submission: Inquiry into the status of the human right to freedom of religion or belief This purpose of this submission is to raise the committee’s awareness that Islam: - militates against “the enjoyment of freedom of religion or belief” - incites to “violations or abuses” of religious freedom - is antithetical and inimical to the “protection and promotion of freedom of religion or belief” Any inquiry into “the human right to freedom of religion or belief” which avoids examining arguably the largest global threat to those freedoms would be abdicating its responsibility to fully inform its stakeholders. Whether it is the nine Islamic countries in the top ten of the World Watch List of Christian Persecution(1), crucifix-wearing “Christians in Sydney fac(ing) growing persecution at the hands of Muslim gangs”(2) or the summary execution of those who blaspheme or apostatise(3), Islam, in practice and in doctrine, militates against “the human right to freedom of religion or belief”. The purpose of this submission is not to illustrate “the nature and extent of (Islamic) violations and abuses of this right” [which are well-documented elsewhere(4)] but to draw the committee’s attention to the Islamic doctrinal “causes of those violations or abuses”. An informed understanding of Islam is crucial to effectively addressing potential future conflicts between Islamic teachings which impact negatively on “freedom of religion or belief” and those Western freedoms we had almost come to take for granted, until Islam came along to remind us that they must be ever fought for. -

Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State 92°10'E 92°20'E 92°30'E Chin Mandalay PALETWA BANGLADESH Ü Rakhine Magway Baw Tu Lar In Tu Lar Bago Tat Chaung Myo Naw Yar Hpar Zay Dar A®vung Tha Pyay San Su Ri Ayeyarwady Kar Lar Day Hpet N N ' ' 0 0 2 !< Myo (Ye Aung Chaung) 2 ° ° 1 Kyaung Toe Mar Zay 1 2 !< !< 2 Bwin (Baung)!< Aung Zan !< Gu Mi Yar Shee Dar !< Ye Aung San Ya Bway V# !< Kyaung Na Hpay (Myo) Kaung Na Phay Ah Nauk Tan Chaung Gaw Yan Ywa Tone Chaung !< !< #0 Ah Shey Htan Chaung (Htan Kar Li) Taing Bin Gar !< !< Ye Bauk Kyar Taung Pyo Sin Thay Pyin #0 !< #0 C! Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Sin Shey Myo Kha Mg Seick (Nord) !< Mi Kyaung Chaung Ah Htet Bo Ka Lay Baw Taw Lar !< !< Ah San Kyaw !< Hlaing Thi !< Nga Yant Chaung Nan Yar Kaing (M) Auk Bo Ka Lay Min Zi Li !< !< Kyee Hnoke Thee V# Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son BANGLADESH #0 Let Yar Chaung Kyaung Zar Hpyu XY Ta Man Thar Ah Shey (Ku Lar) Pan Zi Ta Man Thar (Thet) Ta Man Thar (Ku Lar) Middle !< C! XY Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan C! Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Nga/Myin Baw Kha Mway Ta Man Thar TaunXYg Ta Man Thar Zay Nar/ Tan Tta MXYan Thar (Bo Hmu Gyi Thet) Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (Daing Nat) C! Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar Taungpyoletwea XY Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (!v® Hpaung Seik Taung Pyo Let Yar Mee Taik Ba Da Kar That Kaing Nyar (Thet) BUTHIDAUNG Tha Ra Zaing !< Ah Yaing Kwet Chay C! !<Laung Boke Long Boat Hpon Thi #0 Aung Zay Ya (Nyein Chan Yay) Thin Baw Hla (Ku Lar) That Chaung Pu Zun Chaung !< Gara Pyin Ye Aung Chaung Thin Baw Hla (Rakhine) (Thar -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

Download Report

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Understanding the Fish Market System in Kyauk Phyu Township Rakhine State. Annex to the Final report to DfID Post Giri livelihoods recovery, Kyaukphyu Township, Rakhine State February 14 th 2011 – November 13 th 2011 August 2011 1 Background: Rakhine has a total population of 2,947,859, with an average household size of 6 people, (5.2 national average). The total number of households is 502,481 and the total number of dwelling units is 468,000. 1 On 22 October 2010, Cyclone Giri made landfall on the western coast of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The category four cyclonic storm caused severe damage to houses, infrastructure, standing crops and fisheries. The majority of the 260,000 people affected were left with few means to secure an income. Even prior to the cyclone, Rakhine State (RS) had some of the worst poverty and social indicators in the country. Children's survival and well-being ranked amongst the worst of all State and Divisions in terms of malnutrition, with prevalence rates of chronic malnutrition of 39 per cent and Global Acute Malnutrition of 9 per cent, according to 2003 MICS. 2 The State remains one of the least developed parts of Myanmar, suffering from a number of chronic challenges including high population density, malnutrition, low income poverty and weak infrastructure. The national poverty index ranks Rakhine 13 out of 17 states, with an overall food poverty headcount of 12%. The overall poverty headcount is 38%, in comparison the national average of poverty headcount of 32% and food poverty headcount of 10%. -

(BRI) in Myanmar

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 22 | November 2019 Selling the Silk Road Spirit: China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar Key points • Rather than a ‘grand strategy’ the BRI is a broad and loosely governed framework of activities seeking to address a crisis in Chinese capitalism. Almost any activity, implemented by any actor in any place can be included under the BRI framework and branded as a ‘BRI project’. This allows Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and provincial governments to promote their own projects in pursuit of profit and economic growth. Where necessary, the central Chinese government plays a strong politically support- ive role. It also maintains a semblance of control and leadership over the initiative as a whole. But with such a broad framework, and a multitude of actors involved, the Chinese government has struggled to effectively govern BRI activities. • The BRI is the latest initiative in three decades of efforts to promote Chinese trade and investment in Myanmar. Following the suspension of the Myitsone hydropower dam project and Myanmar’s political and economic transition to a new system of quasi-civilian government in the early 2010s, Chinese companies faced greater competition in bidding for projects and the Chinese Government became frustrated. The rift between the Myanmar government and the international community following the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State provided the Chinese government with an opportunity to rebuild closer ties with their counterparts in Myanmar. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was launched as the primary mechanism for BRI activities in Myanmar, as part of the Chinese government’s economic approach to addressing the conflicts in Myanmar. -

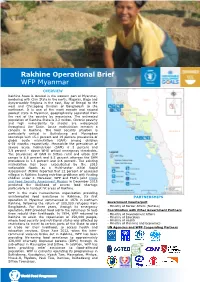

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar OVERVIEW Rakhine State is located in the western part of Myanmar, bordering with Chin State in the north, Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwaddy Regions in the east, Bay of Bengal to the west and Chittagong Division of Bangladesh to the northwest. It is one of the most remote and second poorest state in Myanmar, geographically separated from the rest of the country by mountains. The estimated population of Rakhine State is 3.2 million. Chronic poverty and high vulnerability to shocks are widespread throughout the State. Acute malnutrition remains a concern in Rakhine. The food security situation is particularly critical in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships with 15.1 percent and 19 percent prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children 6-59 months respectively. Meanwhile the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is 2 percent and 3.9 percent - above WHO critical emergency thresholds. The prevalence of GAM in Sittwe rural and urban IDP camps is 8.6 percent and 8.5 percent whereas the SAM prevalence is 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent. The existing malnutrition has been exacerbated by the 2015 nationwide floods as a Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) reported that 22 percent of assessed villages in Rakhine having nutrition problems with feeding children under 2. Moreover, WFP and FAO’s joint Crops and Food Security Assessment Mission in December 2015 predicted the likelihood of severe food shortage particularly in hardest hit areas of Rakhine. WFP is the main humanitarian organization providing uninterrupted food assistance in Rakhine. Its first PARTNERSHIPS operation in Myanmar commenced in 1978 in northern Rakhine, following the return of 200,000 refugees from Government Counterpart Bangladesh. -

The Nature of Islamophobia: a Test of a Tripartite View in Five Countries

Please note: This is a preprint for an article accepted for publication with PSPB. It may be subject to editing and other changes. The nature of Islamophobia: A test of a tripartite view in five countries Fatih Uenal1,2*, Robin Bergh1, Jim Sidanius1, Andreas Zick3, Sasha Kimel4, and Jonas R. Kunst5,6 1 Department of Psychology, Harvard University 2 Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge 3 IKG, University of Bielefeld 4 Department of Psychology, California State University San Marcos 5 Department of Psychology, University of Oslo 6 Center for research on extremism, University of Oslo *Corresponding author Please direct correspondence to Dr. Fatih Uenal, Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge, Old Cavendish Building, Free School Lane, CB2 3RQ, Cambridge, UK, E-mail: [email protected] Word count: 9999 (Excluding title page, tables and figures) Conflict of Interest: None Ethical Approval: This Study partly was approved by Harvard University-Area Committee on the Use of Human Subject (IRB 16-1810). Data Sharing: Please contact the PI for data accessibility. Preregistration: asPredicted #20961 (http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=6sk9gm) Acknowledgements: The research was supported, in part, by a post-doctoral stipend from the Humboldt University Berlin within the Excellence Initiative of the states and the federal government (German Research Foundation). We also want to thank the reviewers and editor for their helpful comments. Page 1 of 256 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Running head: NATURE OF ISLAMOPHOBIA 1 1 2 3 Abstract 4 5 6 This article provides an examination of the structure of Islamophobia across cultures. Our novel 7 8 measure – the Tripartite Islamophobia Scale (TIS) – embeds three theoretically and statistically 9 10 grounded subcomponents of Islamophobia: anti-Muslim prejudice, anti-Islamic sentiment, and 11 12 conspiracy beliefs. -

Liberty University the Religious Persecution of Christians a Thesis

Liberty University The Religious Persecution of Christians A Thesis Project Report Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Divinity In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries By Novella L. Crudup Lynchburg, Virginia November 2018 Copyright Page Copy © 2018 by Novella L. Crudup All rights reserved iii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet ________________________________ Dr. Adam McClendon, Mentor _________________________________ Dr. Micheal Pardue, Reader iv THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Novella L. Crudup Liberty University School of Divinity, 2018 Mentor: Dr. Adam McClendon The thesis project addressed the religious persecution of Christians in Kenya, East Africa, and the United States. The problem is that Christians deny Christ to avoid persecution. There is a need for a proposed solution that emphasizes the need to believe that persecution is a reality, and that every believer should anticipate and prepare for it. Furthermore, the proposed solution should emphasize that God has a purpose for allowing Christians to face persecution. The methodology used for this project was qualitative analysis. The researcher applied the content analysis approach towards interpreting the data that was collected from thirty-one participants completing the questionnaire. The content analysis approach revealed five themes instrumental in developing a proposed solution to the problem. The proposed solution is intended to encourage Christians to have a proper mindset related to God’s Word, recognize the importance of spiritual growth, and maintain a focus on eternal rewards. The proposed solution will help Christians maintain a focus on God before, during, and after periods of persecution. -

American Muslims: a New Islamic Discourse on Religious Freedom

AMERICAN MUSLIMS: A NEW ISLAMIC DISCOURSE ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By John C. R. Musselman, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 13, 2010 AMERICAN MUSLIMS: A NEW ISLAMIC DISCOURSE ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM John C. R. Musselman, B.A. Mentor: Chris Seiple, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In 1998, the U.S. government made the promotion of religious freedom official policy. This policy has often been met with skepticism and hostility from foreign governments and publics. In the Muslim-majority world, it is commonly seen as an attempt to discredit traditional cultural norms and/or Islamic law, as covert support for American missionary activity, and/or as cultural imperialism. American Muslims could play a key role in changing this perception. To date, the American Muslim community has not become deeply invested in the movement for international religious freedom, but their notable absence has not been treated in any substantial length. This thesis draws on the disciplines of public policy, political science, anthropology, and religious studies to explore this absence, in the process attempting to clarify how the immigrant Muslim American community understands religious freedom. It reviews the exegetical study of Islamic sources in relation to human rights and democracy by three leading American Muslim intellectuals—Abdulaziz Sachedina, M.A. Muqtedar Khan, and Khaled Abou El Fadl—and positions their ideas within the dual contexts of the movement for international religious freedom movement and the domestic political incorporation of the Muslim American community.