Reconnaissance Survey of LGBTQ Architectural Resources in the City of Richmond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping . -

Civic Associations

Civic Associations A AVE AZALE W C H S A E B M P O M R B RIV L O I E D N O R H A B R K L E R E K AV R O D RO A B ST WE Y R R O Y N M O A O N N E I A V K W T W E 5 D E A P A 9 E A R G O L I V V O E R T I A E A S 6 5 T FOR E R D 4 9 E O D P I P A I R A T 6 O T 5 D 4 P E 9 R S I E AVE O BELLEVU N BELLEVUE WASHINGTON PARK A V E HERMITAGE ROAD HISTORIC DISTRICT ASSOCIATION K E N P S A 5 REMONT AVE AVE IN T 9 CLA G T T N 1 I R N S E OU T REYC O I 5 G H T 9 O U O R 9 R A S P 5 B N A N O 1 T R I L H O R A N T V E A V I E E A V RNUM AVE V A W LABU V I E R V A E E T RNUM AV 1 E W LABU C A V S VD V 9 BL H O RIC E HEN E E L 5 A V L GINTER PARK I ROSEDALE T A P H W K W R A Y SEDDON ROAD IC WESTHAMPTON CITIZENS ASSOCIATION M R B A I R B A R V A AVE NORTH CENTRAL CIVIC ASSOCIATION T Y M PALMYR PA R D O R O D F A H N A O O THREE CHOPT ROAD CIVIC ASSOCIATION R D VE A S O R OAKDALE A T A R WESTWOOD CIVIC LEAGUE D S E N O A T D PROVIDENCE PARK E V I V E S E 6 A S G 4 D E E A WESTVIEW CIVIC ASSOCIATION A N R O N D L AW I L L V A E F HIGHLAND PARK PLAZA CIVIC ASSOCIATION O E S F L C O MONUMENT AVENUE PARK ASSOCIATION I P E M R R O L I A L LT SHERWOOD PARK CIVIC ASSOCIATION G NOR O O V THS C N IDE K E I AV 6 E S S CLUB VIEW ASSOCIATION GLENBURNIE CIVIC ASSOCIATION 4 T L D RO GINTER PARK TERRACE CIVIC ASSOCIATION T B P R IN H SAUER'S GARDENS CIVIC ASSOCIATION A OO HIGHLAND VIEW H R V D D North Barton Heights A IV E ROA T E WESTHAMPTON PRESERVATION ASSOCIATION L U R R U O 5 W ES AD 9 O SHERWOOD AVE SEX ST HAMPTON GARDENS ASSOCIATION 1 B SHOCKOE HILL CIVIC ASSOCIATION -

Download Guidebook to Richmond

SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA OMNI RICHMOND HOTEL GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 1400 TOWNSEND DRIVE HOUGHTON, MI 49931-1295 www.sia-web.org i GUIDEBOOK EDITORS Christopher H. Marston Nathan Vernon Madison LAYOUT Daniel Schneider COVER IMAGE Philip Morris Leaf Storage Ware house on Richmond’s Tobacco Row. HABS VA-849-31 Edward F. Heite, photog rapher, 1969. ii CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION Richmond’s Industrial Heritage .............................................................. 3 THURSDAY, MAY 31, 2018 T1 - The University of Virginia ................................................................19 T1 - The Blue Ridge Tunnel ....................................................................22 T2 - Richmond Waterfront Walking Tour ..............................................24 T3 - The Library of Virginia .....................................................................26 FRIDAY, JUNE 1, 2018 F1 - Strickland Machine Company ........................................................27 F1 - O.K. Foundry .....................................................................................29 F1 & F2 - Tobacco Row / Philip Morris USA .......................................32 F1 & -

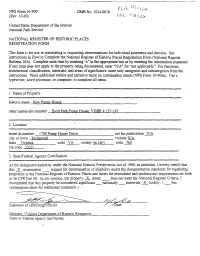

D2JA3%7 Signa6re of Certifying Official Virainia ~Epartmentof Historic Resources State Or Federal Agency Or Tribal Government

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting deteminations for individual properties and districts.See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form(Nationa1Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "xu in the appropriate box or by entering thmionation requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA for "not applicable.Por functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instrutions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ...................................................................................... ...............................................................................................................................................................................1. Name of Property historic name Forest Hill Historic District ..............................................................................................................................................................................other nameslsite number DHR File No. 127-6069 ...................................................................................................................................................................2. -

Draft Bon Air Special Area Plan Detailed Unedited Citizen Comments Compiled from Community Meetings, Emails and Internet Form April/May 2015

Draft Bon Air Special Area Plan Detailed Unedited Citizen Comments Compiled from community meetings, emails and internet form April/May 2015 Comment Response Raw Comment # # Unfortunately, I do not see much in this plan to address the traffic problems that exist along Buford Rd. For cars turning onto/off of Buford, the traffic can be horrendous. Particularly bad is the intersection of Rockaway & Buford but there are other problem spots as well. 1 There is nothing here to address that concern. I would have hoped to see possibly some talk 3 of adding traffic lights or turning some intersections into 4 way stops. Perhaps even banning left turns at certain intersections at certain times of day. In my mind, traffic is one of the biggest issues in this area. On the topic of sidewalks... I know it is a hot button issue. I was initially a huge supporter because it sounds like a great idea. Then I heard the amount of land it takes, and my 2 4, 17 goodness, it changed my mind. Can the trees that would have to be removed be flagged or marked in some way, so as people consider the issue they can SEE the impact? Thank you. As someone who owns property on Bannon Rd., I am not too pleased with this plan. One thing being overlooked is that there is a need for smaller one level single family residence. 3 5 Surely, someone could have developed a plan that did not destroy the established neighborhood that I reside in. I thought this plan was dedicated to preserving what we have. -

SPRING 2013 400 Years of Richmond History in Only 50 Objects

SPRING 2013 400 Years of Richmond History in Only 50 Objects Known by some local citizens as “Richmond’s Attic,” the Valentine Richmond History Center has recently gone global while remaining local with a new exhibition, “A History of Richmond in 50 Objects” (RVA50). Inspired by and paying homage to “A History of the World in 100 Objects,” the groundbreaking partnership of the British Museum and BBC Radio 4 in 2010 that focused on world history through the eyes of one hundred experts, this exhibition continues the dialogue in a way that is uniquely Richmond and was curated by David B. Voelkel, the new Elise H. Wright Curator of General Collections. He used this project as an opportunity to delve into the museum’s holdings of more than 1.5 million objects. RVA50 explores the history of Richmond, Virginia, through a selection of objects from across the general, archives, and costume and textile collections. Creating a balanced exhibition led to many curatorial moments of decision as to inclusion and exclusion as one by one various possible museum artifacts were unearthed from their storage locations for examination and consideration. Each object had to compete for one of the limited 50 spaces not only in historical Continued on page 2 Four Hundred Years... Continued from page 1 significance, but in size, form, and type. The designation of the #1 object is on the historical chronology rather than a ranking of “importance” – a murky place in any instance. From #1 - an 1819 imprint of John Smith’s 1624 Map of Virginia to #50 - the rainbow flag that flew at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond in 2011, RVA50 examines how objects contain layers of meaning that are both personal and public. -

What's out There Richmond

What’s Out There® Richmond Richmond, VA Dear What’s Out There Richmond Visitor, Welcome to What’s Out There Richmond, organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) with support from national and local partners. The materials in this guidebook will inform you about the history and design of this modern city at the Falls of the James River, a place referred to as “Non-such” by colonists to express its incomparability. Please keep and enjoy this guidebook for future explorations of Richmond’s diverse landscape heritage. In 2013, with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, TCLF embarked upon What’s Out There Virginia, a survey of the Commonwealth’s landscape legacy, conceived to add more than 150 significant sites to the What’s Out There online database. As the program matured and our research broadened, TCLF developed What’s Out There Weekend Richmond, the tenth in an ongoing series of city- and regionally-focused tour Photo by Meg Eastman, courtesy Virginia Historical Society events that increase the public visibility of designed landscapes, their designers, and patrons. The two-day event held in October 2014 provided residents and tourists free, expert-led tours of the nearly thirty sites included in this guidebook and are the result of exhaustive, collaborative research. The meandering James River has, through the ages, been the organizing landscape feature of Richmond’s development, providing power to drive industry along with a navigable tidal section and canal network for transportation. The city became the governmental seat for the Confederacy and, following the Civil War and the period of Reconstruction, benefitted from the City Beautiful movement, which promoted symmetry, balance, grandeur, and monumentality. -

Like Nixon to China: the Exhibition of Slavery in the Valentine Museum and the Museum of the Confederacy

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Like Nixon to China: The Exhibition of Slavery in the Valentine Museum and the Museum of the Confederacy Meghan Theresa Naile Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1972 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Like Nixon Going to China”: The Exhibition of Slavery in the Valentine Museum and the Museum of the Confederacy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Virginia Commonwealth University. by: Meghan Theresa Naile Director: Dr. John Kneebone Professor, Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2009 Acknowledgement The author would like to express gratitude to several individuals. I would like to thank the staffs at the Valentine Richmond History Center and the Museum of the Confederacy for all of their friendly help and expertise. I would like to thank the professionals who took time out of their busy schedules to discuss this topic with me: Mr. Gregg Kimball, Mr. John Coski, Mr. Edward D.C. Campbell, Ms. Kym Rice and Mr. Dylan Pritchett. I thank my advisor Dr. Kneebone for his constant encouragement, direction, ideas and patience. I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to my father and my stepmother and their constant support of my education. -

)/.A .. Signature of C&Ifying%Fficial / Date

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and hstricts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "xu in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property hlstoric name New Pumu-House other nameslsite number Bvrd Park Pumu House. VDHR # 127-193 2. Location street &number 1708 Pum~House Drive not for publication NIA city or town Richmond vicinity N/A state Vireinia code VA county (in city) code 760 zip code 23221 - -- 3. StateFederal Agency Certification ---- As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certifv that this X nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally -statewide X locally. -

VIRGINIA Tidewater and Piedmont

Buildings of VIRGINIA Tidewater and Piedmont EDITED BY RICHARD GUY WILSON WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY Sara A. Butler, Edward Chappell Sarah Shields Driggs, Hal Larsen Debra A. McClane, Thomas Tyler Potterfield, Jr. William M. S. Rasmussen, Selden Richardson Edwin Slipek,Jr., Marc C. Wagner, Robert Wojtowicz and Others OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2002 Contents List of Maps, xi Foreword, xiii Acknowledgments, xvii Guide for Users of This Volume, xxi Introduction, 3 The Contours of Eastern Virginia's Built Environment, 5; Native American Habitation, 8; Early Settlement (1607-c. 1720), 10; Eighteenth-Century Change (c. 1720-c. 1780), 15; Nineteenth-Century Prosperity (c. 1780-c. 1840), 18; Decline, Recovery, and the Revival of the Past (c. 1840-c. 1940), 25; Modernism, Tradition, and Large-Scale Growth (c. 1940-c. 2000), 35 Northern Virginia (NV), 42 Arlington County, 44; Fairfax and Prince William Counties, 55 Alexandria (AL), 78 Old Town, 79; West End, 89; Alexandria Suburbs, 91 Northern Piedmont (NP), 95 Loudoun County, 96; Fauquier County, 112 Piedmont (PI), 118 Rappahannock County, 119; Culpeper County, 122; Madison County, 126; Orange County, 128; Hanover County (Western), 132; Goochland County, 134; Louisa County, 135; Fluvanna County, 136; Albemarle County, 137; Greene County, 142 Charlottesville Metropolitan Area (CH), 143 Downtown Area, 143; University of Virginia Campus, 151; Charlottesville Area, 163 x Contents Richmond Metropolitan Area (RI), 169 Capitol Square Area, 174; Court End-East Broad Street, from 14th Street to 3rd Street, 183; -

Welcome to Pump House Park Slopes

JAMES RIVER PARK SYSTEM BEFORE YOU BEGIN: • There is no river access from Pump House Park. • Stay off the tracks. State law allows CSX to arrest and fine you if you are seen on the tracks or ballast. And trains cannot possibly stop in time to save you. • Watch your step and watch your children. This is an historic park with high stone walls and steep Welcome to Pump House Park slopes. A Self-Guided Tour to Richmond’s Most Historic Park 1 Across from the park entrance, TOUR THE TRAILS AND HISTORIC SITES of Pump House Park, the site note the trail sloping up the hill of 1883 Byrd Park Pump House, one of Richmond’s most magnificent toward the Carillon. The trail is on public buildings; Three-Mile Locks, two stone locks for canal boats a black cast iron pipe which used to carry drinking water from the Pump begun in 1838; the Lower Arch, grand entrance to the first operating House up to the reservoir on an earth canal system in the United States and visited by George Washington mound near the tennis courts in on April 12, 1791. Byrd Park. 2 See the kiosk, a volunteer project, for more about canals in America and for the latest park announce- ments. 3 The stone building like a church is the Byrd Park Pump House, complet- ed in 1882 in the Victorian Gothic style. Canal water entered through the round pipe and was pumped up the reservoir by nine force pumps in the basement. The pumps were oper- ated by water power, the water enter- ing through the three square open- ings, turning wheels, and exiting 20 feet below into the lower canal. -

For Sale | Fan District Mixed Use Investment Property

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 607 E BROADWAY FOR SALE | FAN DISTRICT MIXED USE INVESTMENT PROPERTY 2501 W MAIN ST RICHMOND, VA 23220 $990,000 PID: W0001117014 3,645 SF (0.08 AC) Parcel 3,142 SF Building Area 450 SF Basement Area 1 Commercial Unit 1 Residential Unit 468 SF Detached Garage UB Urban Business Zoning PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY COMMERCIAL 4 PHOTOS UNIT 8 RICHMOND’S FAN DISTRICT 9 DEMOGRAPHICS & MARKET DATA 10 MULTIFAMILY MARKET ANALYSIS 1 11 LOCATION MAP RESIDENTIAL UNITS 12 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM UB URBAN BUSINESS ZONING 3,645 SF PARCEL AREA Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of 2501 W Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed 3,142 SF to the One South Commercial listing team. BUILDING AREA Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money 450 SF Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. BASEMENT Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum.