Rail Transport in NATO's Logistics System: the Case of Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: a Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 15 The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J. Lamb, with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified com- batant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: President Bill Clinton addressing Croat-Muslim Federation Peace Agreement signing ceremony in the Old Executive Office Building, March 18, 1994 (William J. Clinton Presidential Library) The Bosnian Train and Equip Program The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power By Christopher J. Lamb with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 15 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. March 2014 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

CTEF) the Estimated Cost of This Report Or Study for the Department of Defense Is Approximately $7,720 for the 2020 Fiscal Year

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE BUDGET FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2021 February 2020 Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) COUNTER-ISLAMIC STATE OF IRAQ AND SYRIA (ISIS) TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND (CTEF) The estimated cost of this report or study for the Department of Defense is approximately $7,720 for the 2020 Fiscal Year. This includes $150 in expenses and $7,570 in DoD labor. Generated on 2020Feb05 RefID: 4-83DDD29 UNCLASSIFIED FY 2021 OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS (OCO) REQUEST COUNTER-ISIS TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND (CTEF) TABLE OF CONTENTS: Page I. Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Summary 3 II. Iraq Program Summary 4 A. Iraq Ministry of Defense Program Summary 5 B. Iraq Counter Terrorism Service Program Summary 6 C. Iraq Ministry of Interior Program Summary 6 D. Iraq Ministry of Peshmerga Program Summary 7 III. Requirements in Iraq By Financial Activity Plan Category 8 A. Training and Equipping 8 B. Logistical Support, Supplies, and Services 19 C. Stipends 19 D. Infrastructure Repair, and Renovation 19 E. Sustainment 20 IV. Impact if Not Funded 23 1 COUNTER-ISIS TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED FY 2021 OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS (OCO) REQUEST COUNTER-ISIS TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND (CTEF) V. Syria Program Summary 25 VI. Requirements in Syria By Financial Activity Plan Category 27 A. Training and Equipping 27 B. Logistical Support, Supplies, and Services 32 C. Stipends 33 D. Infrastructure Repair, and Renovation 33 E. Sustainment 34 VII. Impact if Not Funded 34 2 COUNTER-ISIS TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED FY 2021 OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS (OCO) REQUEST COUNTER-ISIS TRAIN AND EQUIP FUND (CTEF) I. -

Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments Lobyrev, Vitaly and Tikhomirov, Andrey and Tsukarev, Taras and Vinokurov, Evgeny Eurasian Development Bank, Institute of Economy and Transport Development 10 May 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/86705/ MPRA Paper No. 86705, posted 18 May 2018 16:33 UTC BELT AND ROAD TRANSPORT CORRIDORS: BARRIERS AND INVESTMENTS Authors: Vitaly Lobyrev; Andrey Tikhomirov (Institute of Economy and Transport Development); Taras Tsukarev, PhD (Econ); Evgeny Vinokurov, PhD (Econ) (EDB Centre for Integration Studies). This report presents the results of an analysis of the impact that international freight traffic barriers have on logistics, transit potential, and development of transport corridors traversing EAEU member states. The authors of EDB Centre for Integration Studies Report No. 49 maintain that, if current railway freight rates and Chinese railway subsidies remain in place, by 2020 container traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis may reach 250,000 FEU. At the same time, long-term freight traffic growth is restricted by a number of internal and external factors. The question is: What can be done to fully realise the existing trans-Eurasian transit potential? Removal of non-tariff and technical barriers is one of the key target areas. Restrictions discussed in this report include infrastructural (transport and logistical infrastructure), border/customs-related, and administrative/legal restrictions. The findings of a survey conducted among European consignors is a valuable source of information on these subjects. The authors present their recommendations regarding what can be done to remove the barriers that hamper international freight traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis. -

The American Civil War: a War of Logistics

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR: A WAR OF LOGISTICS Franklin M. Welter A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2015 Committee: Rebecca Mancuso, Advisor Dwayne Beggs © 2015 Franklin M. Welter All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Rebecca Mancuso, Advisor The American Civil War was the first modern war. It was fought with weapons capable of dealing death on a scale never before seen. It was also the first war which saw the widespread use of the railroad. Across the country men, materials, and supplies were transported along the iron rails which industrial revolution swept in. Without the railroads, the Union would have been unable to win the war. All of the resources, men, and materials available to the North mean little when they cannot be shipped across the great expanse which was the North during the Civil War. The goals of this thesis are to examine the roles and issues faced by seemingly independent people in very different situations during the war, and to investigate how the problems which these people encountered were overcome. The first chapter, centered in Ohio, gives insight into the roles which noncombatants played in the process. Farmers, bakers, and others behind the lines. Chapter two covers the journey across the rails, the challenges faced, and how they were overcome. This chapter looks at how those in command handled the railroad, how it affected the battles, especially Gettysburg, and how the railroads were defended over the course of the war, something which had never before needed to be considered. -

Long Freight Trains in Poland, What Is the Problem of Its Usage?

PRACE NAUKOWE POLITECHNIKI WARSZAWSKIEJ z. 111 Transport 2016 Krzysztof Lewandowski _"G#"G+@V"G @Y"*" LONG FREIGHT TRAINS IN POLAND, WHAT IS THE PROBLEM OF ITS USAGE? The manuscript delivered: April 2016 Abstract: The article presents an analysis of possibility of usage of long freight trains in Poland for connection with the modern Silk Railway to China. The desire to use freight trains with a length of more than 600 meters in Poland encounters several problems on the existing infrastructure. Limita- tions of usage are found here. Also, it presents possible ways for long freight trains. Keywords: long freight train, limitation, usage, Poland 1. INTRODUCTION The first step to create a new connection to China was made in 1990 just before collapsed the Soviet Union. In next year, 1991, many countries retrieved the independence. The idea of reviving east – west trade on the old Silk Road was raised by the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the USSR, Eduard Shevardnadze in September 1990 at the Vladivostok Interna- tional Conference. In several years was many conferences to create the new transport cor- ridor Transport Corridor Europe–Caucasus–Asia (TRACECA) through Armenia, Azerbai- jan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Tajikistan, Tur- key, Ukraine and Uzbekistan [47]. On 1999 Poland and Ukraine signed memorandum "XL - Odessa [49]. On 2014 was increased the tensions between Kyiv and Moscow. In spring 2014, Russia began a military invasion on the Crimea peninsula and military conflict in eastern Ukraine. Russia decided to create sanctions against Ukraine and began to limit the free transit for Ukrainian goods through its territory. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers 2017 Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda Lukas Dregne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dregne, Lukas, "Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda" (2017). Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 175. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda." Sir, the state, in choosing men to serve it, takes no notice of their opinions; if they be willing to serve it, that satisfies. I advised you formerly to bear with minds of different men from yourself. Take heed of being sharp against those to whom you can object little but that they square not with you in matters of religion. - Cromwell, To Major General Crawford (1643) Lukas Dregne B.A., History, Political Science University of Montana 1 Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Abstract: Oliver Cromwell has always been a subject of fierce debate since his death on September 3, 1658. The most notorious stain blotting his reputation occurred during the conquest of Ireland by forces of the English Parliament under his command. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized /,00V .3 / 49 3 - fdoA 3 / 49 C/ -Z e4 ReportNo. 8431-POL STAFF APPRAISALREPORT Public Disclosure Authorized POLAND FIRST TRANSPORTPROJECT APRIL 5, 1990 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized InfrastructureOperations Division CountryDepartment IV Europe,Middle East and North Africa Region This documenthas a restricted distributionand may be used by recipients only in the performanceof their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCYAND EOUIVALENTUNITS CurrencyUnit - Zloty (ZL) (Averagerates) May Dec. Jan. 1986 1987 1988 1989 1989 1990 1 US$ 175 265 430 850 4900 9500 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System US System 1 meter (m) 3.2808 feet (ft) 1 kilometer (km) - 0.6214 mile (mi) 2 1 square kilometer (kin) - 0.3861 square mile (Mi) 1 metric ton (m ton) = 0.9842 long ton (lg ton) 1 kilogram (kg) - 2.2046 pounds (lbs) ABBREVIATIONSAND ACRONYMS AADT - Annual Average Daily Traffic ABS - AutomaticBlock System COCOM - CoordinatingCommittee for MultilateralExports CTC - CentralizedTraffic Control GDDP - DirectorateGeneral of Public Roads GNP - Gross National Product LOT - Polish Airlines MIS ManagementInformation System MTME - Ministryof Transportand Maritime Economy MY - Marshalling Yard NBP - National Bank of Poland OMIS OperatingManagement Information System PEKAES - InternationalRoad Freight Company PKP - Polish State Railways PKS - NationalRoad TransportEnterprise PMS - PavementManagement System POL - Polish Ocean Lines PSK Polish Domestic FreightForwarders S & T - Signallingand Telecommunications TM - Traffic Management TMIS - TransportManagement Information System UIC - InternationalRailway Union ZNTKS - Enterprisefor the Repair of Rolling Stock at Stargard ZwUS - Signal Equipment Works POLAND: FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 FOR OMCIAL UE ONLY STAFF APPRAISALREPORT POLAND FIRST TRANSPORTPROJECT Table of Contents Pag-eNo. -

Transformation of the Chojnice Railway Junction in the Years 1989-2017 and Future Operational Perspectives

Transport Geography Papers of Polish Geographical Society 2018, 21(4), 30-43 DOI 10.4467/2543859XPKG.18.020.10778 Received: 20.11.2018 Received in revised form: 20.12.2018 Accepted: 21.12.2018 Published: 29.12.2018 TRANSFORMATION OF THE CHOJNICE RAILWAY JUNCTION IN THE YEARS 1989-2017 AND FUTURE OPERATIONAL PERSPECTIVES Przekształcenia węzła kolejowego w Chojnicach w latach 1989-2017 i perspektywy jego funkcjonowania w przyszłości Damian Otta (1), Renata Anisiewicz (2), Tadeusz Palmowski (3) (1) Association of Rail Enthusiasts in Chojnice, Strzelecka 68, 89-600 Chojnice, Poland E-mail: [email protected] (2) Departament of Regional Development, Institute of Geography, Faculty of Oceanography and Geography, University of Gdańsk, Jana Bażyńskiego 4, 80-309 Gdańsk, Poland E-mail: [email protected] (3) Departament of Regional Development, Institute of Geography, Faculty of Oceanography and Geography, University of Gdańsk, Jana Bażyńskiego 4, 80-309 Gdańsk, Poland (corresponding author) E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Otta D., Anisiewicz R., Palmowski T., 2018, Transformation of the Chojnice railway junction in the years 1989-2017 and future operational perspectives, Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG, 21(4), 30-43. Abstract: The paper presents changes in the operation of the railway junction in Chojnice and neighbouring areas, and the impact thereof in the years 1989-2017. The analysis covers infrastructural changes, passenger traffic and organisational changes resulting from the transformation of the Polish State Railways (PKP) after 1989. The Chojnice railway junction, operating since the seventies of the nineteenth century is one of the biggest junctions in northern Poland. -

A Student's Guide in Poland

This guidebook was prepared thanks to the collaboration of the Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP), the Foundation for the Development of the Education System (FRSE) and the Erasmus Students Network Poland (ESN Poland). First edition author: Maciej Rewucki Contributors: Joanna Maruszczak Justyna Zalesko Pola Plaskota Wojciech Skrodzki Paulina Wyrwas Text editor: Leila Chenoir Layout: ccpg.com.pl Photos: Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP) Erasmus Students Network Poland (ESN Poland) Foundation for the Development of the Education System (FRSE) Adam Mickiewicz University Students’ Union Bartek Burba Monika Chrustek Martyna Kamzol Łukasz Majchrzak Igor Matwijcio Patrycja Nowak Magdalena Pietrzak Bartek Szajrych Joanna Tomczak Adobe Stock First edition: September 2020 CONTENTS Preface by PSRP, ESN and FRSE PAGE 1 Welcome to Poland PAGE 2 Basic information about Poland PAGE 3 Where to find support during your first days in Poland? PAGE 4 PSRP and ESN PAGE 4 Higher education in Poland PAGE 10 Transportation in Poland PAGE 12 Other discounts and offers for students PAGE 14 Weather PAGE 15 Healthcare PAGE 16 Students with disabilities PAGE 17 Student unions in Poland PAGE 18 Bank account PAGE 19 Where to find accommodation? Tips and online sources PAGE 20 Mobile phones and Internet PAGE 22 Important contacts PAGE 23 Student life in Poland PAGE 25 Jobs for foreigners in Poland PAGE 26 Where to look for a job? PAGE 26 Polish culture PAGE 27 Food PAGE 30 Prices and expenses in Poland PAGE 32 Formalities PAGE 33 Basic Polish phrases PAGE 34 Hello, Together with the Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP), the European Student Network (ESN) Poland we welcome you to Poland. -

AMU Welcome Guide | 5 During the 123 Years Following the 1795 and German, Offered by 21 Faculties on 1

WelcomeWelcome Guide Guide Welcome Guide The Project is financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the Welcome to Poland Programme, as part of the Operational Programme Knowledge Education Development co-financed by the European Social Fund Welcome from the AMU Rector 3 Welcome from AMU Vice-Rector for International Cooperation 4 1. AdaM Mickiewicz UniversitY 6 1.1. Introduction 6 1.2. International cooperation 7 1.3. Faculties 9 Poznań campus 9 Kalisz campus – Faculty of Fine Arts and Pedagogy 9 Gniezno campus – Institute of European Culture 10 Piła campus – Nadnotecki Institute 10 Słubice campus – Collegium Polonicum 10 1.4. Main AMU Library (ul. Ratajczaka, Poznań) 11 1.6. School of Polish Language and Culture 13 2. Study witH us! 14 2.1. Calendar 14 Table of 2.2. International Centre is here to help! 16 2.3. Admission 17 Content 2.3.1. Enrolment in short 21 2.4. Dormitories 23 2.5. NAWA Polish Governmental Scholarships 24 2.6. Student organizations and Science Clubs 26 2.7. Activities for Students 27 3. LivinG In POlanD 32 3.1. Get to know our country! 32 3.2. Travelling around Poland 34 3.3. Health care 37 3.4. Everyday life 40 3.5. Weather 45 3.6. Documents 47 3.7. Migrant Info Point 49 4. PoznaŃ anD WIelkopolska – your neW home! 50 4.1. Welcome to our region 50 4.2. Explore Poznań 51 4.3. Cultural offer 57 4.4. Be active 60 4.5. Make Polish Friends 61 4.6. Enjoy life 62 4.7. -

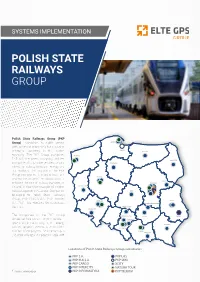

Implementation for Polish State Railways Group

SYSTEMS IMPLEMENTATION POLISH STATE RAILWAYS GROUP Polish State Railways Group (PKP Group) combines its public service GDYNIA with activity characteristic for a modern GDAŃSK enterprise operating in the market OLSZTYN economy. The PKP Group comprises SZCZECIN PKP S.A., the parent company, and ten BIAŁYSTOK companies that provide services, among BYDGOSZCZ others, on railway transport, energy and ICT markets. The mission of the PKP Group companies is to build trust and POZNAŃ improve the image of the railway, so as to SIEDLCE enhance the role of railway transport in WARSZAWA Poland, following the example of modern ZIELONA GÓRA railways operating in Europe. Companies ŁÓDŹ belonging to Polish State Railways Group: PKP CARGO S.A., PKP Intercity WROCŁAW LUBLIN S.A., PKP Linia Hutnicza Szerokotorowa SKARŻYSKO-KAMIENNA Sp. z o.o.. CZĘSTOCHOWA WAŁBRZYCH The companies of the PKP Group TARNOWSKIE GÓRY KIELCE ZAMOŚĆ altogether hire almost 70,000 people – SOSNOWIEC specialists in the railway, IT, ICT, energy RZESZÓW and real property sectors. In terms of the KATOWICE KRAKÓW number of employees, the PKP Group is NOWY SĄCZ the second largest employer in Poland.[1] Locations of Polish State Railways Group subsidiaries. PKP S.A. PKP LHS PKP PLK S.A. PKP SKM PKP CARGO XCITY PKP INTERCITY NATURA TOUR [1] Source: www.pkp.pl PKP INFORMATYKA PKP TELKOM ET GPS Positioning system The ET GPS system is designed to monitor the position of locomotives and wagons. GPS tracker saves the object location, speed, direction of movement and information from sensors and interfaces. The data saved in the internal memory of the GPS tracker are transferred to the monitoring system. -

Latest Developments at Czech Railways

Feature Transition to Market Economy Latest Developments at Czech Railways Jirˇí Havlícˇek The political changes that occurred after 1989 throughout Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) following the collapse of Table 1 Basic Czech Railways (CD) Statistics communism have affected every society in the region. The Czech Republic (CR) 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 has been no exception. All these changes Freight 123.729 108.762 108.859 107.235 103.360 93.521 have also affected railway transport in the (million tonnes) CR. In addition to changes in manage- Freight (million tonne-km) 25,140 22,703 22,623 22,338 20,739 18,294 ment methods, the former Czechoslovak Passengers State Railways (CSD) was split into two 242.182 228.720 227.147 219.244 202.877 181.977 (million) separate companies—Czech Railways Passengers (CD) and Slovak Railways (ZSR)—as part (million passenger 8,548 8,481 8,023 8,111 7,710 7,001 of the separation of Czechoslovakia into -km) the Czech and Slovak Republics. This article describes the latest developments at CD from the viewpoints of economy and technology. Providing railway services in the CR is passenger and freight volumes in 1998 made more complex by the fact that three were 182 million passengers (7,001 million Basic Information on Czech electrification systems are in use: 25 kV/ passenger-km) and 93.521 million tonnes Railways 50 Hz AC, and 3000 and 1500 V␣ DC. (18,294 million tonne-km), respectively. The CR railway network is one of the The total number of CD employees at 1 Czech Railways is a state organization densest in the world.