Case Study 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Better Governance for Wales Key Materials

Better Governance for Wales – key material: Statements and Debates, September 2005 – November 2005 Abstract This paper draws together the key statements and debates relating to the White Paper ‘Better Governance for Wales’ from September to November 2005. It includes transcripts of proceedings from the Assembly and Westminster. The paper will be updated regularly by the Members’ Research Service. December 2005 Members’ Research Service / Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau Members’ Research Service: Research Paper Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Papur Ymchwil Better Governance for Wales – key material Statements and debates, September 2005 – November 2005 Members’ Research Service December 2005 Paper number: 05/0040/mrs © Crown copyright 2005 Enquiry no: 05/0040/mrs Date: December 2005 This document has been prepared by the Members’ Research Service to provide Assembly Members and their staff with information and for no other purpose. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information is accurate, however, we cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies found later in the original source material, provided that the original source is not the Members’ Research Service itself. This document does not constitute an expression of opinion by the National Assembly, the Welsh Assembly Government or any other of the Assembly’s constituent parts or connected bodies. Members’ Research Service: Research Paper Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Papur Ymchwil Contents 1 Statement by the Rt Hon Rhodri Morgan AM, First Minister on the White Paper, ‘Better Governance for Wales’ during Questions to the First Minister, 20 September 2005 .............................................................................................................. 1 2 Debate on the Report of the Committee on the Better Governance for Wales White Paper in the Assembly, 21 September 2005 ...................................................... -

CREATING a DIGITAL DIALOGUE How Can the National Assembly for Wales Use Digital to Build Useful and Meaningful Citizen Engagement?

CREATING A DIGITAL DIALOGUE How can the National Assembly for Wales use digital to build useful and meaningful citizen engagement? Digital News and Information Taskforce CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................. 5 SECTION 2: DISCUSSION ...........47 Foreword by Chair ...................................6 The Assembly as a Content Background .................................................9 Platform .......................................................49 Remit ............................................................... 11 Telling the National Assembly’s Stories ............................... 50 Membership .............................................. 12 Platforms ....................................................57 Recommendations ............................... 14 Specialist Audiences ...........................64 Summary ....................................................20 Digital and Data Leadership in the Assembly .................................... 80 SECTION 1: CONTEXT...................31 Staying Ahead ..........................................91 The Welsh Media Market Since 1999 ................................................................ 32 ANNEXES ........................................93 The Digital Eco-system in Wales ........................................................40 Annex 1: Meetings and Discussions Held ..94 Other Parliaments ................................ 42 Annex 2: The objective of the National Assembly for Wales – Membership .............................................96 Content -

Sustainability: Annual Report 2019-20

Welsh Parliament Senedd Commission Sustainability: Annual Report 2019-20 June 2020 www.senedd.wales The Welsh Parliament is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people. Commonly known as the Senedd, it makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the Senedd website: www.senedd.wales Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Welsh Parliament, Cardiff Bay, CF99 1SN 0300 200 6565 [email protected] www.senedd.wales SeneddWales SeneddWales Senedd © Senedd Commission Copyright 2020 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the Senedd Commission and the title of the document specified. Welsh Parliament Senedd Commission Sustainability: Annual Report 2019-20 June 2020 www.senedd.wales On 6 May we became the Welsh Parliament; the Senedd. As the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020 received Royal Assent in January, it marked the culmination of a long and complicated pro- cess for the many Commission colleagues who were involved in its passage. Despite our new title, you will notice this document mostly refers to the institution as the Assembly; a reflection of the fact we’re looking back over the past 12 months before the change to our name. Sustainability: Annual Report 2019-20 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... -

C17 Land Disposal Old Signal Box, Cardiff

Les Waters Senior Manager, Licensing Railway Markets and Economics Telephone 020 7282 2106 E-mail: [email protected] Company Secretary Network Rail Infrastructure Limited 1 Eversholt Street London NW1 2DN 9 January 2020 Network licence Condition 17 (land disposal): railway embankment and decommissioned signal box, Cardiff Central station Decision 1. On 11 November 2019, Network Rail gave notice of its intention to dispose of land siting railway embankment land and a decommissioned signal box at Cardiff Central station, Wales (“the land”), in accordance with Condition 17 of its network licence. The land is described in more detail in the notice (copy attached). 2. We have considered the information supplied by Network Rail including the responses received from third parties consulted. For the purposes of Condition 17 of Network Rail’s network licence, ORR consents to the disposal of the land in accordance with the particulars set out in its notice. Reasons for decision 3. We are satisfied that Network Rail has consulted relevant stakeholders with current information and no objections were received. 4. In considering the proposed disposal, we note that: there is no evidence that current or future railway operations would be affected adversely; Road Rail Access to the track will be retained; and the proposals will lead to the re-profiling of the embankment and the installation of a new retaining wall, to be approved and supervised by Network Rail. 5. Network Rail confirmed subsequently that the disposal would not preclude the proposals to increase train capacity at Cardiff Central station under DfT’s Rail Network Enhancements Pipeline scheme.1 1 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/840709/rail-network- enhancements-pipeline.pdf Page 1 of 2 Head Office: 25 Cabot Square, London E14 4QZ T: 020 7282 2000 www.orr.gov.uk 6. -

Devolution Decade

spring 2009 Production Editor: John Osmond Devolution Decade Assistant Editor: Nick Morris Associate Editors: On the face of it the verdicts we publish in this issue by leading protagonists in Geraint Talfan Davies, Rhys David the 1997 referendum on the first ten years of the National Assembly make pretty depressing reading. Professor Kevin Morgan, who chaired the Yes Campaign, is Administration: Helen Sims-Coomber, Clare Johnson especially damning. He lets us in to what he describes as “devolution’s dirty little secret”, its failure to make a fist of developing the Welsh economy. And the Design: statistics are incontrovertible. In terms of our prosperity relative to most other www.theundercard.co.uk parts of the United Kingdom, we’ve actually gone backwards in the first decade To advertise – declining from 77 to 75 per cent of the UK’s average GVA. When we started Tel: 029 2066 6606 out the Assembly Government’s stated ambition was to climb to 90 per cent by Institute of Welsh Affairs 2010, an aspiration that has been quietly dropped. One way or another our other 4 Cathedral Road contributors all point to the economy as the central reason for their Cardiff CF11 9LJ disappointment with devolution’s record so far. Tel: 029 2066 0820 Yet a narrow focus on the economy, important as it undoubtedly is, leads Email: [email protected] to a zero sum game. Devolution is about much more than that. And anyway, www.iwa.org.uk as Kevin Morgan himself concedes, the amount that government can do to The IWA is a non-aligned independent think- influence the economy will always be limited, especially a government with so tank and research institute, based in Cardiff with relatively little control over the main economic levers as the one in Cardiff Bay. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2015–16

Delivery and transition Annual report and accounts 2015–16 July 2016 National Assembly for Wales Assembly Commission The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this report can be found on the National Assembly’s website: www.assembly.wales Copies of this report can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @assemblywales We welcome calls via the Text Relay Service. © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2016 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. Delivery and transition Annual report and accounts 2015–16 July 2016 National Assembly for Wales Assembly Commission Contents Our performance: overview.................................................................................................. 1 Llywydd’s foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction from Chief Executive and Clerk ..................................................................................... -

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

Jane Hutt: Businesses That Have Received Welsh Government Grants During 2011/12

Jane Hutt: Businesses that have received Welsh Government grants during 2011/12 1 STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES 100 PERCENT EFFECTIVE TRAINING 1MTB1 1ST CHOICE TRANSPORT LTD 2 WOODS 30 MINUTE WORKOUT LTD 3D HAIR AND BEAUTY LTD 4A GREENHOUSE COM LTD 4MAT TRAINING 4WARD DEVELOPMENT LTD 5 STAR AUTOS 5C SERVICES LTD 75 POINT 3 LTD A AND R ELECTRICAL WALES LTD A JEFFERY BUILDING CONTRACTOR A & B AIR SYSTEMS LTD A & N MEDIA FINANCE SERVICES LTD A A ELECTRICAL A A INTERNATIONAL LTD A AND E G JONES A AND E THERAPY A AND G SERVICES A AND P VEHICLE SERVICES A AND S MOTOR REPAIRS A AND T JONES A B CARDINAL PACKAGING LTD A BRADLEY & SONS A CUSHLEY HEATING SERVICES A CUT ABOVE A FOULKES & PARTNERS A GIDDINGS A H PLANT HIRE LTD A HARRIES BUILDING SERVICES LTD A HIER PLUMBING AND HEATING A I SUMNER A J ACCESS PLATFORMS LTD A J RENTALS LIMITED A J WALTERS AVIATION LTD A M EVANS A M GWYNNE A MCLAY AND COMPANY LIMITED A P HUGHES LANDSCAPING A P PATEL A PARRY CONSTRUCTION CO LTD A PLUS TRAINING & BUSINES SERVICES A R ELECTRICAL TRAINING CENTRE A R GIBSON PAINTING AND DEC SERVS A R T RHYMNEY LTD A S DISTRIBUTION SERVICES LTD A THOMAS A W JONES BUILDING CONTRACTORS A W RENEWABLES LTD A WILLIAMS A1 CARE SERVICES A1 CEILINGS A1 SAFE & SECURE A19 SKILLS A40 GARAGE A4E LTD AA & MG WOZENCRAFT AAA TRAINING CO LTD AABSOLUTELY LUSH HAIR STUDIO AB INTERNET LTD ABB LTD ABER GLAZIERS LTD ABERAVON ICC ABERDARE FORD ABERGAVENNY FINE FOODS LTD ABINGDON FLOORING LTD ABLE LIFTING GEAR SWANSEA LTD ABLE OFFICE FURNITURE LTD ABLEWORLD UK LTD ABM CATERING FOR LEISURE LTD ABOUT TRAINING -

Research Briefing: Low Carbon Heat

National Assembly for Wales Senedd Research Research Briefing: Low Carbon Heat www.assembly.wales/research The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/research Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Research Service National Assembly for Wales Tŷ Hywel Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6316 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddResearch Blog: SeneddResearch.blog © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2018 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Senedd Research Research Briefing: Low Carbon Heat Author: Robert Abernethy, Jeni Spragg and Sean Evans Date: June 2018 Paper number: 18-042 This briefing paper is the third in a series on low carbon energy in Wales. This part focuses on low carbon heat sources, including their role in decarbonisation and an overview of relevant technologies. The Research Service acknowledges the parliamentary fellowships provided to Robert Abernethy and Jeni Spragg by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, which enabled this briefing paper to be completed. -

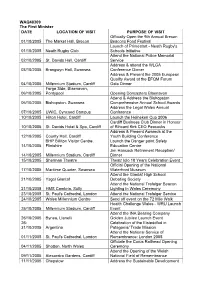

WAQ48309 the First Minister DATE LOCATION OF

WAQ48309 The First Minister DATE LOCATION OF VISIT PURPOSE OF VISIT Officially Open the 9th Annual Brecon 01/10/2005 The Market Hall, Brecon Beacons Food Festival Launch of Primestart - Neath Rugby's 01/10/2005 Neath Rugby Club Schools Initiative Attend the National Police Memorial 02/10/2005 St. Davids Hall, Cardiff Service Address & attend the WLGA 03/10/2005 Brangwyn Hall, Swansea Conference Dinner Address & Present the 2005 European Quality Award at the EFQM Forum 04/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Gala Dinner Forge Side, Blaenavon, 06/10/2005 Pontypool Opening Doncasters Blaenavon Attend & Address the Bishopston 06/10/2005 Bishopston, Swansea Comprehensive Annual School Awards Address the Legal Wales Annual 07/10/2005 UWIC, Cyncoed Campus Conference 10/10/2005 Hilton Hotel, Cardiff Launch the Heineken Cup 2006 Cardiff Business Club Dinner in Honour 10/10/2005 St. Davids Hotel & Spa, Cardiff of Rihcard Kirk CEO Peacocks Address & Present Awareds at the 12/10/2005 County Hall, Cardiff Youth Building Conference BHP Billiton Visitor Centre, Launch the Danger point Safety 14/10/2005 Flintshire Education Centre Jim Hancock Retirement Reception/ 14/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Dinner 15/10/2005 Sherman Theatre Theatr Iolo 18 Years Celebration Event Official Opening of the National 17/10/2005 Maritime Quarter, Swansea Waterfront Museum Attend the Glantaf High School 21/10/2005 Ysgol Glantaf Debating Society Attend the National Trafalgar Beacon 21/10/2005 HMS Cambria, Sully Lighting in Wales Ceremony 23/10/2005 St. Paul's Cathedral, London Attend the National Trafalgar Service 24/10/2005 Wales Millennium Centre Send off event on the 72 Mile Walk Health Challenge Wales - WRU Launch 25/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Event Attend the INA Bearing Company 26/10/2005 Bynea, Llanelli Golden Jubilee Launch Event 26- Celebration of the Eisteddfod in 31/10/2005 Argentina Patagonia/ Trade Mission Attend the National Service of 01/11/2005 St. -

Brief Histories of Churches Cardiff

Brief Histories of Churches in the Roath, Splott, Adamsdown, Cathays, Tremorfa, Tredegarville & Penylan areas of Cardiff Roath Local History Society in Cardiff has as its area of interest the old Parish of Roath in the 1880s. This covered not just the area we know as Roath today but also Splott, Adamsdown, Pengam, Pen-y-lan, and part of Cathays. This brief histories of churches looks at the churches that would have been in the area of old parish of Roath but also strays into neighbouring area such as Tredegarville and Cathays as a whole. There may be more churches to be included such as some mission halls that doubled up both as Sunday Schools as well as a church. A couple of synagogues are also included. Building of other faiths will be added over time, though some are already listed as former church buildings now house other faiths. Some errors and omissions in the details are likely. When the author is made aware of any errors, or additional information comes to light, the details on the website version will be updated where possible. The website also contains an interactive map that pinpoints the individual churches. Research for this compilation has relied heavily on a number of publications by members of Roath Local History Society in particular: ‘Cardiff Churches Through Time’ by Jean Rose. ‘Roath, Splott and Adamsdown, One Thousand Years of History’ by Jeff Childs. ‘Roath, Splott and Adamsdown – the Archive Photographs Series’ by Jeff Childs The author would also like to thank members of the various churches listed for their assistance and individuals of other organisations. -

Tall Buildings Supplementary Planning Guidance

Appendix D Tall Buildings Supplementary Planning Guidance Draft for approval City of Cardiff Council January 2017 1 Mae’r ddogfen hon hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg / This document is also available in Welsh Front cover: physical model of tall building proposal in Cardiff city centre, Rio Architects / Watkins Jones / Skyline2 Contents 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 The location of tall buildings 8 3.0 Sustainable transport, parking guidance and community facilities 10 4.0 Skyline, strategic views and vistas 11 i. City centre 12 ii. Areas outside the city centre 13 5.0 Historic environment setting 16 6.0 The design of tall buildings 18 i. Mixed land uses 19 ii. The form and silhouette of the building 20 iii. Quality and appearance 20 iv. Impact and interface at street level 21 v. Sustainable building design 24 7.0 Affordable housing guidance and design for living 26 8.0 Open space requirements 28 9.0 Pre-application discussion 30 10.0 Design and access statements 32 Appendices 35 Appendix A: Diagram: city centre and Cardiff Bay aerial photo 35 Appendix B: Consultation representations and responses 36 3 1. Introduction City centre public space with views to proposed elegant, reflective tall buildi ng (far right), Comcast Innovation and Technology Centre, Philadelphia4 Dbox / Foster & Partners 1.0 Introduction Policy context 1.1 This Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) supplements policies in the adopted Cardiff Local Development Plan (LDP) relating to good quality and sustainable design and more specifically tall buildings 1.2 Welsh Government support the use of SPG to set out detailed guidance on the way in which development plan policies will be applied in particular circumstances or areas.