Gacha,” Or Loot Box Gambling in Social-Network Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Law of Property and Obligations

146 WASEDA BULLETIN OF COMPARATIVE LAW Vol. 28 2.First Session on October 12, 2008 Reports: (5)“Standards of Judicial Review” Masaomi Kimizuka(Professor, Yokohama National University). (6)“Theories of Discretion and Theories of Human Rights” George Shishido(Professor, Hitotsubashi University). (7)“Unconstitutionality and Illegality” Tatsuya Fujii(Professor, Tsukuba University). (8)“Confirmational Litigation as ‘Fundamental Right Litigation’” Hiroyuki Munesue(Professor, Osaka University). 3. Second Session on October 7, 2007 Reports: (9)“Non-‘cases and controversies’ Litigation and Judicial Power” Keiko Yamagishi(Professor, Chukyo Univeristy). (10)“Remedies for Governmental Omission” Mitsuru Noro(Professor, Osaka University). (11)“Temporary Remedies” Ryuji Yamamoto(Professor, Tokyo University). (12)“The Activated Circumstances of Constitutional and Administrative Litigation” Norihiko Sugihara(Judge, Tokyo District Court). 2. Law of Property and Obligations The Japan Association of Private Law held its 72nd General Meeting at Nagoya University on October 12 and 13, 2008. First Day: Reports: First Section (1)“Rents and Fixtures as Security for the Mortgage Loan―From a Cash Flow Control Perspective” DEVELOPMENTS IN 2008 ― ACADEMIC SOCIETIES 147 Noriyuki Aoki(Associate Professor, Waseda University). (2)“Die Neuorientierung des Persönlichkeitsrechts” Kazunari Kimura(Lecturer, Setsunan University). (3)“Pure Economic Loss Due to Defective Buildings” Akiko Shindo(Associate Professor, Hokkaido University). (4)“‘Consideration of Relative Fault’ in the Law of Unjustified Enrichment―A suggestion from the Common Law” Akimichi Sasakawa(Associate Professor, Kobe Gakuin University). Second Section (1)“La dissuation et la sanction dans la responsabilité civile” Masako Hiromine(Associate Professor, Kobe Gakuin University). (2)“Rücktritt und § 541 jZGB” Junkou Toyama( Associate Professor, Otaru University of Commerce). (3)“Das Beurteilungskriterium der Teilnichtigkeit” Katsuhiro Kondo(Associate Professor, Fukushima University). -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Yoko HAMADA Faculty of Law, Okayama University 3-1-1 Tsushimanaka, Kita-ku Okayama, 700-8530 JAPAN [email protected] (+81) 86-251-7501 Education Mar 2003 Completed the Doctoral Program without dissertation, Kyushu University, Graduate School of Law, (Fukuoka, Japan) Mar 2000 Master in Law, Kyushu University, Graduate School of Law (Fukuoka, Japan) Mar 1998 Bachelor in Law, Kyushu University, Faculty of Law (Fukuoka, Japan) Professional Experience Apr 2010 - present Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Okayama University (Okayama, Japan) Specialized in and teach Civil Procedure, Civil Execution, and Insolvency Law Apr 2008 - Mar 2010 Associate Professor, Faculty of Law and Politics, Tezukayama University (Nara, Japan) Specialized in and teach Civil Procedure and Insolvency Law Apr 2003 - Mar 2008 Lecturer, Faculty of Law and Politics, Tezukayama University (Nara, Japan) Specialized in and teach Civil Procedure and Insolvency Law Teaching Experience Sep 2016 – present Part-time Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Okayama Shoka University (Okayama, Japan) Teach Civil Procedure Sep 2007 - Mar 2008 Part-time Lecturer, Faculty of Contemporary Social Studies, Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts (Kyoko, Japan) Teach Civil Procedure Sep 2006 - Mar 2009 Part-time Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Doshisha University (Kyoto, Japan) Teach Civil Procedure Apr 2005- Aug 2005 Part-time Lecturer, College of Law, Ritsumeikan University (Kyoko, Japan) Teach Civil Procedure Research Support Apr 2010 – Mar 2014 Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Publications Articles A Study on Liquidation Proceedings under Qualifies Acceptance and Bankruptcy from Procedural Perspectives, Okayama Law Review Vol. -

Lecture Notes in Physics

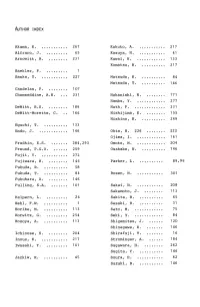

AUTHOR INDEX Akama, K ............ 267 Kakuto, A ............. 217 Alfraro, J .......... 65 Kasuya, N ............ 41 Arnowitt, R ......... 231 Kawai, H ............. 133 Komatsu, H ........... 217 Baekler, P .......... I Banks, T ............ 227 Matsuda, H ........... 84 Matsuda, T ........... 146 Candelas, P ......... 107 Chamseddine, A.H .... 231 Nakanishi, N ......... 171 Nambu, Y ............. 277 DeWitt, B.S ......... 189 Nath, P .............. 231 DeWitt-Morette, C. .. 166 Nishijima, K ......... 155 Nishino, H ........... 249 Eguchi, T ........... 133 Endo, J ............. 146 Ohta, N. 226 ........ 222 Ojima, I ............. 161 Fradkin, E.S ........ 284,293 Omote, M ............. 204 Freund, P.G.O ....... 259 Osakabe, N ........... 146 Fujii, Y ............ 272 Fujiwara, H ......... 146 Parker, L ........... 89,96 Fukuda, R ........... 58 Fukuda, T ........... 84 Rosen, N ............ 301 Fukuhara, A ......... 146 Fulling, S.A ........ 101 Sakai, N ....... ..... 208 Sakamoto, J ......... 113 Halpern, L .......... 26 Sakita, B ............ 65 Hehl, F.W ........... I Sasaki, R ........... 31 Horibe, M ........... 113 Sato, M ............. 75 Horwitz, G .......... 254 Seki, Y ............. 84 Hosoya, A ........... 113 Shigemitsu, J ....... 120 Shinagawa, K ........ 146 Ichinose, S ......... 204 Shirafuji, T ........ 16 Inoue, K ............ 217 Strominger, A ....... 184 Iwasaki, Y .......... 141 Sugawara, H ......... 262 Sugita, Y ........... 146 Jackiw, R ........... 45 Suura, H ............ 62 Suzuki, R ........... 146 307 Takeshita, S ........ 217 Tauber, G.E ......... 301 Tomimatsu, A ........ 36 Tonomura, A ......... 146 Townsend, P.K ....... 240 Tseytlin, A.A ....... 284,293 Umezaki, H .......... 146 Viallet, C.M ........ 116 Yokoyama, K ......... 84 Yoneya, T ........... 79 Yoshi4, T ........... 141 List of Participants Akama, K. DeWitt, B.S. Saitama Medical School Department of Physics Japan University of Texas at Austin USA Aoki, K. RIFP, Kyoto University DeWitt-Morette, C. Japan Department of Astronomy University of Texas at Austin USA Arafune, J. -

List of Reviewers

IATSS Research 34 (2011) I–II Contents lists available at ScienceDirect IATSS Research Acknowledgement : Reviewers 2010 Below is the list of current IATSS Research reviewers in our database (as of December 2010) and experts who assisted paper review for Vol.34 publication. We would like to express sincere gratitude for their cooperation. ACARMAN, Tankut FUKUDA, Atsushi (Associate Professor, Galatasaray University, Turkey) (Professor, Nihon University, Japan) AKAHANE, Hirokazu FUKUYAMA, Kei (Professor, Chiba Institute of Technology, Japan) (Professor, Tottori University, Japan) BARTH, Matthew FWA, Tien Fang (Professor & Director, University of California Riverside, USA) (Professor, National University of Singapore, Singapore) BHAT, Chandra GUO, Konghui (Professor, University of Texas Austin, USA) (Professor, Jilin University, China) BJÖRNSTIG, Ulf HASEGAWA, Takaaki (Professor, Umea University, Sweden) (Professor, Saitama University, Japan) BRILON, Werner HASSON, Patrick PE (Professor Emeritus, Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany) (Manager, FHWA Resource Center, USA) BROGGI, Alberto HAUER, Ezra (Professor & Director, Universita di Parma, Italy) (Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto, Canada) CHANG, Jason SK HIMENO, Kenji (Professor, National Taiwan University, Taiwan) (Professor, Chuo University, Japan) CHUJO, Ushio KAMEYAMA, Shuichi (Professor, Keio University, Japan) (Professor, Hokkaido Institute of Technology, Japan) CRANDALL, Jeff R KISHII, Takayuki (Professor & Director, University of Virginia, USA) (Professor, Nihon University, Japan) -

Japanese Branch Report

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2003 Japanese Branch Report Itsuyo Shimizu Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Shimizu, Itsuyo, "Japanese Branch Report" (2003). The George Eliot Review. 461. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/461 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JAPANESE BRANCH REPORT By Itsuyo Shimizu The sixth annual convention of the George Eliot Fellowship of Japan was held at Tezukayama University in an ancient city, Nara, on Saturday 30 November 2002. Before the opening, the members who arrived early enjoyed Romola (a silent film directed by Henry King, 1924) and opera music (arranged by Kiyoko Tsuda, a head official of the Japanese branch). The morning session began with an opening address by Kiyoko Tsuda, a professor at Tezukayama University. In the morning, four members read their papers under the chairmanship of Professor Yoshiko Tanaka and Professor Shigeko Tomita. The first paper, 'Women in Scenes of Clerical Life', was presented by Mariko Asano, a part time lecturer at Konan University. She pointed out that the gradual moral progress in MilIy, Caterina, and Janet was the prototype of women's lives represented in George Eliot's later works. The second paper, 'Birth and Significance of Felix Halt, the Radical: George Eliot's Groping and Challenge', was presented by Teiko Hashimoto, an assistant professor at Showa Pharmaceutical University. -

Curriculum Viate Hideo Yunoue

CURRICULUM VIATE HIDEO YUNOUE ADDRESS Associate Professor Graduate School of Economics, Nagoya City University 1 Yamanohata Mizuho-cho, Mizuho-ku, Nagoya, Aichi, 467-8501, Japan yunoue [at] econ.nagoya-cu.ac.jp PERSONAL DETAILS Date of birth: February 6th, 1980 Place of birth: Hyogo, Japan Citizenship: Japan EDUCATION March 2009 Ph.D. in Economics , Osaka University Thesis: Economic Growth and Public Policy in Political Economy March 2004 M.A. in Applied Economics, Osaka University March 2002 B.A. in Policy Studies, Kwansei Gakuin University FIELDS OF INTEREST Public Economics, Political Economy, Local Public Finance, Economic Growth PROFESSIONAL POSITION [Full-Time] 04/2005{03/2007 Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 04/2008{03/2009 Assistant Professor, Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University 04/2009{03/2012 Assistant Professor, School of Service Innovation, Chiba University of Commerce 04/2012{03/2013 Associate Professor, School of Service Innovation, Chiba University of Commerce 04/2013{03/2019 Associate Professor, School of Economics, University of Hyogo 04/2019{Present Associate Professor, Graduate School of Economics, Nagoya City University [Part-Time] 04/2006{03/2007 Teaching Assistant, Economics B (Prof. Shin Saito), Osaka University 04/2006{03/2007 Teaching Assistant, Statistical Analysis (Prof. Mototsugu Fukushige), Osaka Univer- sity 1 04/2007{09/2008 Lecturer, Introduction to Japanese Economy, Tezukayama University 04/2007{03/2008 Lecturer, Economic Statistics, Tezukayama -

Evolang9 Participants List

Evolang9 Participants List 1. Ai Kawakami { Graduate School of Fine art, Tokyo University of the Arts/Emotional Information Joint Research Laboratory, RIKEN, BSI 2. Akihiko Takahashi { Kyoto University 3. Akihiro Tanaka { Waaseda University 4. Akiko Nagao { Kagawa Univeristy, Center for Research and Educational Development in Higher Education 5. Akira Honda { Kobe City University of Foreign Studies 6. Aleksandrs Berdicevskis { University of Bergen 7. Alessandra Tomaselli { Universit`adegli Studi di Verona Dipartimento di Lingue e Letterature Straniere 8. Alexander Mehler { Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main 9. Alexander Woodward { University of Tokyo 10. Alexandra Holoborodko { Hitotsubashi University Graduate School of Sociolinguistics 11. Alice Alexandra McGreevey { University of Edinburgh 12. Anatoly Polikarpov { Lomonosov Moscow State University 13. Andrea Baronchelli { Department of Physics, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Bouve' College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University 14. Andrew Martin { RIKEN Brain Science Institute 15. Andrew D. M. Smith { University of Stirling 16. Andy L¨ucking { Goethe-Universit¨atFrankfurt am Main 17. Angel Gallego { Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona 18. Anja Latrouite { Institut f¨urSprache und Information Heinrich-Heine- Universit¨at 19. Anna Maria Di Sciullo { Universite du Quebec a Montreal 20. Anne van der Kant { University of Anwerp 21. Antonio Benitez-Burraco { University of Huelva 22. Archishman Raju { St. Stephen's College 23. Arimoto Yoshiko { JST, ERATO Okanoya Emotional Information Project 24. Aritz Irurtzun { CNRS-Iker (UMR 5478) 25. Arnaud Rey { Laboratoire de Psychologie Cognitive - UMR7290 Aix- Marseille University 1 26. Asako Ucihbori { Nihon University 27. Atsuko Ikegashira { Otsuma Woman's University 28. Atsushi Iriki { Riken Brain Science Institute 29. Aya Ihara { National Institute of Information and Communications Tech- nology 30. -

Discussion Papers in Economics and Business

Discussion Papers In Economics And Business Welfare and Tax Policies in a Neoclassical Growth Model with Non-unitary Discounting Ryoji Ohdoi, Koichi Futagami and Takeo Hori Discussion Paper 15-14 Graduate School of Economics and Osaka School of International Public Policy (OSIPP) Osaka University, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, JAPAN Welfare and Tax Policies in a Neoclassical Growth Model with Non-unitary Discounting Ryoji Ohdoi, Koichi Futagami and Takeo Hori Discussion Paper 15-14 May 2015 Graduate School of Economics and Osaka School of International Public Policy (OSIPP) Osaka University, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, JAPAN Welfare and Tax Policies in a Neoclassical Growth Model with Non-unitary Discounting∗ Ryoji Ohdoiy Koichi Futagamiz Takeo Horix Tokyo Institute of Technology Osaka University Aoyama Gakuin University Abstract In this paper, we propose a neoclassical growth model with non-unitary discount- ing, where an individual discounts her future utilities from consumption and leisure differently. Because this non-unitary discounting induces the individual's preference reversals, we regard one individual as being composed of different selves. Then we derive the closed-form solution of the recursive competitive equilibrium in which her different selves behave in a time-consistent way in all periods. With regard to welfare analysis, we obtain the following three main results. First, the selves in any period strictly prefer the planning allocation to the laissez-faire allocation if they are given the same value of a state variable in both situations. Second, the selves in the long run can prefer the latter to the former allocation if we focus on the overall equilibrium paths in both situations. -

A Aichi University, Aichi Gakuin University

A Aichi University, www.aichi-u.ac.jp Aichi Gakuin University, www.aichi-gakuin.ac.jp Aichi Medical University, www.aichi-med-u.ac.jp Aichi Prefectural University, www.aichi-pu.ac.jp Aichi Prefectural College of Nursing Health, www.aichi-nurs.ac.jp Aichi Institute of Technology, www.aitech.ac.jp Aichi University of Education, www.aichi-edu.ac.jp Aichi Shukutoku University, www.aasa.ac.jp The University of Aizu, www.u-aizu.ac.jp Asia University, www.asia-u.ac.jp Akita University, www.akita-u.ac.jp Akita Prefectural University, www.asia-pu.ac.jp/graduate/ Aomori University, www.aomori-u.ac.jp Aomori Public College, www.nebuta.ac.jp Aoyama Gakuin University , www.aoyama.ac.jp Asahi University, www.asahi-u.ac.jp Asahikawa University, www.asahikawa-u.ac.jp Asahikawa Medical College, www.asahikawa-med.ac.jp Ashikaga Institute of Technology, www.ashitech.ac.jp Azabu University, www.azabu-u.ac.jp B Baika Women’s College, www.baika.ac.jp Baiko Gakuin University, www.baiko.ac.jp Beppu University, www.beppu-u.ac.jp Bukkyo University, www.bukkyo-u.ac.jp Bunka Women’s University, www.bunka.ac.jp Bunkyo University, www.bunkyo.ac.jp Bunkyo Gakuin University, www.u-bunkyo.ac.jp/wu/ C Chiba University, www.chiba-u.ac.jp Chiba Keizai University, www.cku.ac.jp Chiba Institute of Technology, www.it-chiba.ac.jp Chiba University of Commerce, www.cuc.ac.jp Chitose Institute of Science and Technology, www.chitose.ac.jp Chubu University, www.chubu.ac.jp Chukyo University, www.chukyo-u.ac.jp Chuo University, www.chuo-u.ac.jp D Daido Institute of Technology, www.daido-it.ac.jp -

Universities Offering University Transfer Program (Undergraduate Courses)

日本学生支援機構(Japan Student Services Organization) Universities offering university transfer program (Undergraduate courses) ■ Information included the transfer programs offered at the undergraduate level by Japanese national, local public and private universities which are available for international students. ■ Courses which are exclusively for international students, regardless of his/her country of origin and nationality, are also available (Japanese students will also participate in the same course). ■ Application information available for international students from specific schools (an overseas school which has concluded an exchange student agreement with a university in Japan, an affiliated school or etc), Japanese Government Monbukagakusho (MEXT) Scholarship students, international students who are dispatched by foreign governments and other types of specific students, is not listed here. Only information about applications which are also available for privately-financed international students is recorded. ■ Certain portion of information in the column of date of implementation under item no. 10 is also included of schedules which are yet to be confirmed. You are advised to contact respective schools for updated information. ■ Search for schools (graduate schools, universities and junior colleges) 11. Date of https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/planning/search-school/daigakukensaku.html implementation 7. Medium of Instruction 8. Target persons B = Both of International student 9. Pre-arrival admission system 1. School Type J Japanese (100%) and Japanese student E English (100%) I = International student only It is a selection system which allows applicants to remind at their J = E Japanese and English (50%) J = Japanese student included N = National home country and obtains the J > E Japanese, English S = Please ask to the University L = Local permission for admission. -

Population Association of Japan

Population Association of Japan 2005 Annual Meeting Program June 4 – 5, 2005 Kobe University 2-1 Rokkodai, Nada-ku Kobe 658-8501 Japan TEL.+81-78-881-1212 President ATO, Makoto Chair, Organizing Committee TAKAHASHI, Shinichi Program Summary Saturday 4 June 09:00 Registration 09:30~12:30 Theme Session 1: Population Decline and Society from Regional Perspective( 2F 232 ) General Session 1 3F 324 General Session 2 3F 320 General Session 3 2F 230 12:30~13:30 Lunch Break 12:30~13:30 PAJ Board of Director’s Meeting 13:30~14:00 Presidential Lecture ( 2F 232 ) 14:00~14:10 Welcome Address from the Host Organization ( 2F 232 ) 14:10~15:00 General Membership Meeting ( 2F 232 ) 15:00~18:00 Symposium: Future of the Japanese Baby Boom Generation ( 2F 232 ) 18:15~20:00 Welcome Reception ( Academic Hall 3F Restaurant “Sakura” ) Sunday 5 June 08:30 Registration 09:00~12:30 Theme Session 2: Emergence of Lowest-low Fertility and Policy Responses in Some Asian Countries ( 2F 232 ) General Session 4 ( 3F 324 ) General Session 5 ( 3F 320 ) General Session 6 ( 2F 230 ) 12:30~13:30 Lunch Break 13:30~17:00 Theme Session 3: Diversification of Union Formation ( 2F 232 ) General Session 7 ( 3F 324 ) General Session 8 ( 3F 320 ) General Session 9 ( 2F 230 ) 2 Population Association of Japan 2005 Annual Meeting Program Saturday 4 June 9:30~12:30 9 : 00 Registration Theme Session 1 (Room No. 232) Population Decline and Society from Regional Perspective Organizer / Chair:ISHIKAWA, Yoshitaka(Kyoto University) Discussant:INOUE, Takashi(Aoyama Gakuin University) ABE, Takashi(Japan -

126 協43EDA BUL乙ET刀V of COMB4R,4Tlve Law Vb乙18

126 協43EDA BUL乙ET刀V OF COMB4R,4TlVE LAw Vb乙18 9. lnternatiOnal LaW 1. 跳εノヒzpαn6s6Asso6i‘π∫on6ゾノ1n∫8配αガonαl Lαvレheld its1997Spring Session(the100th Amual Meeting),celebrating the Centennial of the Association at the University of Tokyo on May10and11,1997,The programs were as follows: Common Theme:A Hundred Years of Intemational Legal Studies in Japan ∫丁漉Fか訂Dαy1 (1)Keynote address President:Ybshio KAWASHIMA (Professor,Tezukayama University) Keynote speaker:Soji YAMAMOTO (Professor,Sophia University) “Developments of Logics and lnstitutionalisation of Domes- tic Applicability of Intemational Law in Jap&n” (2) Report on Research Chaiman:Wakamizu TSUTSUI(Professor,Waseda University) Reponler: Hisakazu FUJITA.(Professor,University of Tokyo) “Evolution des6tudes sur le droit de la guelTe au Japon pen- dant un siさcle” (3) Reports on Research Chairman:Tadao KURIBAYASHI (Professor,Keio Gijuku University) Reporter: Naoya OKUWAKI(Profbssor,Rikkyo University) “The Concept of Tenitoriality in Intemational Law and the Japanese Intemational Legal Studies:Effectiveness and Legit- imacy of‘Tenitorial Sovereignty’” Reporter: Osamu NAKAMURA(Professor,Kobe University) “The Evolution of the Study of Intemational Organizations in Japan” (4)Reports on Research DEvELOPル歪E:2vTS刀〉1997-ACADEMIC SOCIET認S 127 Chairman:Jutaro HIGASHI(Professor,Tsuda College) Reporter: 丁欲ane SUGIHARA(Profbssor,Kyoto University) “The Functional Limitation of Judicial Settlement Role in Intemational A(Uudication” Reporter: Shinya MURASE(Profbssor,Sophia University) “Studies on the Sources