The Broadway Shows of Edward Gorey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3s2006vg Online items available Guide to the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions Collection Processing Information: Arrangement and description by Deborah Kennedy, David C. Tambo, Yolanda Blue, Louisa Dennis, and Elizabeth Witherell; also student assistants Elizabeth Aburto, Julie Baron, Marisela Bautista, Liz Bittner, Michelle Bowden, Chris Caldow, Jacqueline Chau, Alison Church, Hubert Dubrulle, Sivakumar Elambooranan, Richard Frausto, Michael Fry, Joseline Garde, Joseph Gardner, Tim Hagen, Arlene Hebron, Kara Heerman, M. Pilar Herraiz, Ain Hunter, Sandra Jacobs, Derek Jaeger, Gisele Jones, Julie Kravets, Annie Leatt, Kurt Morrill, Chris Shea, Robert Simons, Kay Wamser, Leon Zimlich, and other Library and Special Collections staff and student assistants; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou. Latest revision D. Tambo. Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 2000 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Center for the Study Mss 18 1 of Democratic Institutions Collection Guide to the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions (CSDI) Collection, 1950-1991 [bulk dates 1961-1987] Collection number: Mss 18 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Contact Information: Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html Processing Information: Arrangement and description by Deborah Kennedy, David C. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography Or Autobiography Year Winner 1917

A Monthly Newsletter of Ibadan Book Club – December Edition www.ibadanbookclub.webs.com, www.ibadanbookclub.wordpress.com E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography or Autobiography Year Winner 1917 Julia Ward Howe, Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott assisted by Florence Howe Hall 1918 Benjamin Franklin, Self-Revealed, William Cabell Bruce 1919 The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams 1920 The Life of John Marshall, Albert J. Beveridge 1921 The Americanization of Edward Bok, Edward Bok 1922 A Daughter of the Middle Border, Hamlin Garland 1923 The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1924 From Immigrant to Inventor, Michael Idvorsky Pupin 1925 Barrett Wendell and His Letters, M.A. DeWolfe Howe 1926 The Life of Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing 1927 Whitman, Emory Holloway 1928 The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas, Charles Edward Russell 1929 The Training of an American: The Earlier Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1930 The Raven, Marquis James 1931 Charles W. Eliot, Henry James 1932 Theodore Roosevelt, Henry F. Pringle 1933 Grover Cleveland, Allan Nevins 1934 John Hay, Tyler Dennett 1935 R.E. Lee, Douglas S. Freeman 1936 The Thought and Character of William James, Ralph Barton Perry 1937 Hamilton Fish, Allan Nevins 1938 Pedlar's Progress, Odell Shepard, Andrew Jackson, Marquis James 1939 Benjamin Franklin, Carl Van Doren 1940 Woodrow Wilson, Life and Letters, Vol. VII and VIII, Ray Stannard Baker 1941 Jonathan Edwards, Ola Elizabeth Winslow 1942 Crusader in Crinoline, Forrest Wilson 1943 Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison 1944 The American Leonardo: The Life of Samuel F.B. -

American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Film and Media Studies Arts and Humanities 2001 American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing Tom Stempel Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Stempel, Tom, "American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing" (2001). Film and Media Studies. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_film_and_media_studies/7 American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing This page intentionally left blank American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing Tom Stempel THJE UNNERSITY PRESS OlF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 2001 by Tom Stempel Published by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College ofKentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stempel, Tom, 1941- American audiences on movies and moviegoing I by Tom Stempel. p. em. Includes bibliographical references. -

The Pulitzer Prizes Winners An

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award...................................................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service................................................................................................................7 Reporting...................................................................................................................25 Local Reporting...........................................................................................................28 Local Reporting, Edition Time....................................................................................33 Local General or Spot News Reporting.......................................................................34 General News Reporting..............................................................................................37 Spot News Reporting...................................................................................................39 Breaking News Reporting............................................................................................40 Local Reporting, No Edition Time...............................................................................46 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting.................................................................48 Investigative Reporting................................................................................................51 Explanatory Journalism...............................................................................................61 -

Diss Filing Draft 12-6-17

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Talk Performance: Extemporaneous Speech, Artistic Discipline, and Media in the Post-1960s American Avant-garde A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Theatre & Drama By Ira S. Murfin EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 © Copyright by Ira S. Murfin 2017 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation narrates the circulation and institutionalization of an emergent category of talk performance within the late-twentieth century US avant-garde through the career trajectories of three artists from disparate disciplinary backgrounds working in and around the 1970s: theatrical monologist Spalding Gray, poet David Antin, and dance artist and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. All established themselves through more obviously discipline-coherent work before turning to extemporaneous talk as a performance strategy within the shifting critical and cultural environments of post-1960s avant-gardes. Undertaking a comparative study collecting these practices under the label talk performance, this project uncovers the processes by which these artists both resisted and relied upon disciplinary structures, and the media technologies and formats that attend those structures, to configure their work within particular arts discourses. Talk performance becomes a provocative site for understanding how minimalist interventions into formal disciplinary categories helped define the reapportionment of the overall art situation in the aftermath of the 1960s along lines of rhetorical and institutional distinction that still persist. Employing newly available multimedia archives and a historiographic approach to the various narrow disciplinary accounts of the late-twentieth-century American avant-garde that have become standard, this project recuperates traces of an unacknowledged, interdisciplinary set of talk performance practices. -

Biography Today: Author Series

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 390 725 SO 025 415 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Author Series. Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers. Volume 1,1995. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7808-0014-1 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 217p. AVAILABLE FROMOmnigraphics, Inc., 2500 Penobscot Building, Detroit, MI 48226. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Books (010) Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL C1T Biography Today: Author Series; vl 1995 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Language Arts; *Popular Culture; Profiles; Reading Interests; *Recreational Reading: Social Studies; *Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials ABSTRACT The serialized reference work "Biography Today" is initiating a "Subject Series" that in five separate volumes will encompass: authors, artists, scientists, and inventors, sports figures, and world leaders. This is the first volume in the "Author Series.' There will be no duplication between the regular series and the special subject volumes. This volume contains 19 biographical sketches. Each entry provides at least one photograph of the individual profiled, with bold-faced rubrics informing the reader on the author's birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. Obituary entries also are included, written to provide a perspective on the individual's entire career. U.S. authc sin this volume include:(1) Eric Carle;(2) Alice Childress;(3) Robert Cormier;(4) Jim Davis;(5) John Grisham; (6) Virginia Hamilton; (7)S. E. Hinton; (8)M. E. Kerr;(9) Stephen King;(10) Gary Larson;(11) Joan Lowery Nixon;(12) Gary Paulsen; (13) Cynthia Rylant;(14) Mildred D. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI May 10 , 2001 I, Scott Hermanson, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: The Department of English It is entitled: The Simulation of Nature: Contemporary American Fiction in an Environmental Context Approved by: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Stanley Corkin, Ph.D. James Wilson, Ph.D. i The Simulation of Nature: Contemporary American Fiction in an Environmental Context A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by Scott Hermanson B.S., Northwestern University 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1996 Committee Chair: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. ii Abstract The dissertation is an examination of how nature is socially constructed in particular texts of contemporary American Fiction. In discussing the novels of Thomas Pynchon, Richard Powers, and Jonathan Franzen, and the non-fiction of Mike Davis, I argue that their works accurately depict how nature is created because they recognize the idea of nature as a textual artifact. Fully aware of their textual limitations, these works acknowledge and foreground the ontological uncertainty present in their writing, embracing postmodern literary techniques to challenge the notion that "nature" is a tangible, stable, self-evident reality. They embrace the fictionality of language, admitting that any textual enterprise can only aspire to simulation. The dissertation begins by exploring the simulated nature of Walt Disney's Animal Kingdom. -

Top 30 July/05

Top 50 U.S. Business Media Beat Maps and Contact Dossiers For PR Professionals PUBLISHED BY Top 50 U.S. Consumer Media Beat Maps and Contact Dossier for PR Professionals is published by Infocom Group 5900 Hollis Street, Suite L Emeryville, CA 94608-2008 (510) 596-9300 Richard Carufel / Editor Mike Billings/ Research Services Manager James Sinkinson / Publisher All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, electronic, mechanical, photographic, recorded, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. © 2007 by Infocom Group For more information about Infocom Group publications, please call toll-free (800) 959-1059. All information in this book has been verified through February 15, 2007. Contents National TV & Cable CNN . .1 E! Entertainment TV . .2 CBS’s “The Early Show” . .3 “Entertainment Tonight” . .4 The Food Network . .4 “Good Morning America” . .4 Home & Garden TV . .5 “Live with Regis and Kelly” . .5 Martha Stewart Living TV . .6 The Oprah Winfrey Show . .6 “Today” Show . .7 Magazines AARP: The MagazIne . .7 Better Homes and Gardens . .7 Bon Appetit . .8 Conde Nast Traveler . .9 Cooking Light . .10 Cosmopolitan . .10 Elle . .11 Entertainment Weekly . .12 Esquire . .14 Family Circle . .14 Glamour . .15 Good Housekeeping . .17 Gourmet . .17 GQ . .17 Health . .18 InStyle . .19 Ladies’ Home Journal . .20 Marie Claire . .20 Maxim . .21 Men’s Health . ..22 Newsweek . .22 O, The Oprah Magazine . .24 Parents . .25 People . .26 Prevention . .29 Redbook . .30 Rolling Stone . .30 Self . .31 Seventeen . .32 Time . .33 US Weekly . .35 Vanity Fair . -

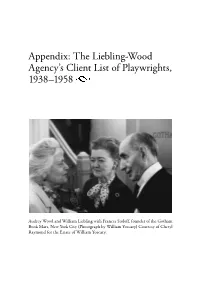

Appendix: the Liebling-Wood Agency's Client List of Playwrights, 1938–1958

A p p e n d i x : T h e L i e b l i n g - W o o d Agency’s Client List of Playwrights, 1938–1958 Audrey Wood and William Liebling with Frances Stoloff, founder of the Gotham Book Mart, New York City (Photograph by William Yoscary) Courtesy of Cheryl Raymond for the Estate of William Yoscary. 174 Appendix Audrey Wood’s client list at Liebling-Wood was extended for another 23 years beyond the sale of the Liebling-Wood Agency and her reloca- tion, first, to Music Corporation of America, and, second, to the Ashley- Steiner-Famous Agency (later, International Creative Management). Katharine Albert Robert Anderson Jean Anouilh Don Appell Harold Arlen Robert Ayres Marie Baumer Bertram Bloch Allen Boretz Bertolt Brecht Jane Bowles Marc Connelly Luther Davis Mel Dinelli Friedrich Düerrenmatt Vernon Duke Jack Dunphy Jacques Duval Mignon Eberhart Dale Eunson John Finch Doris Frankel Claiborne Foster Ketti Frings Charlcie Garrett Oliver Garrett Michael Gazzo E. B. Ginty Jean Giraudoux C. Givens Jay Gorney E. Y. (“Yip”) Harburg Roy Hargrave Sig Herzig Dorothy Heyward DuBose Heyward William Inge Appendix 175 Orrin Jannings Fay Kanin Michael Kanin Jean Kerr Walter Kerr H. S. Kraft Searle Kramer Herbert Kubly Clare Kummer John LaTouche Charles Laughton Isabel Leighton Carl Leo Vera Matthews Carson McCullers John Murray Liam O’Brien Edward Paramore Ernest Pascal John Pen Leo Rifkin Howard Rigsby Cecil Robson Lynn Root Fred Saidy George Seaton David Shaw Elsa Shelly Arnold Sundgaard Frank Tarloff Julian Thompson Dan Totheroh Maurice Valency F. Wakeman Robert Wallston Hagar Wilde Tennessee Williams Calder Willingham Donald Windham Eva Wolas N o t e s INTRODUCTION Epigraph: From a one-page hand-out of quotes by Audrey Wood prepared for the dedication of the Audrey Wood Theatre, New York City, on September 24, 1984, Audrey Wood Papers, HRC. -

Reviewing a Whirl of Books

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, IssUE 4 Reviewing a Whirl of Books CLEMENTE BOTELHO Study and respond to an author’s work from many perspectives — feature, interview and review. INSIDE The Book Writing Literary Preparation Writing Charts A Book of a Great President 5 Life 12 16 Review 29 December 8, 2008 © 2008 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, ISSUE 4 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program About Reviewing a Whirl of Books Lesson: Writing a book review enhances Book World is awhirl with possibilities. Book reviews appraise reading skills; critical thinking; analytic, the latest releases and, occasionally, remind us of works that evaluative and explanatory abilities; and deserve dusting off for a second reading. Works for young composition fluency. adult readers, works of fiction and nonfiction, biography, global Level: Low to High affairs, society, science and travel. Subjects: English, Reading Related Activity: Journalism, AP English The Book World staff and guest critics direct busy readers to Language and Composition books that are excellent uses of their time or are questionable purchases. Books that would make great gifts, engage a child or please a Sinophile. Their reviews are mini-lectures, introducing new topics in history, culture, and the arts and sciences to be explored. In The Writing Life, authors share insights, inspirations and demons they have confronted as writers. They tell how a phrase mesmerized, a good pen directed, a translator improved and style developed. Book World editor Marie Arana provides a short bio that reveals another dimension of each writer’s life. This guide’s content includes book reviews to study as models, a close reading technique, guidelines to writing a book review, and exercises in reading charts and doing online research of publishing companies.