American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

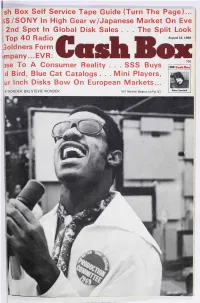

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP on SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 Min)

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 min) Directed and written by Samuel Fuller Based on a story by Dwight Taylor Produced by Jules Schermer Original Music by Leigh Harline Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald Richard Widmark...Skip McCoy Jean Peters...Candy Thelma Ritter...Moe Williams Murvyn Vye...Captain Dan Tiger Richard Kiley...Joey Willis Bouchey...Zara Milburn Stone...Detective Winoki Parley Baer...Headquarters Communist in chair SAMUEL FULLER (August 12, 1912, Worcester, Massachusetts— October 30, 1997, Hollywood, California) has 53 writing credits and 32 directing credits. Some of the films and tv episodes he directed were Street of No Return (1989), Les Voleurs de la nuit/Thieves After Dark (1984), White Dog (1982), The Big Red One (1980), "The Iron Horse" (1966-1967), The Naked Kiss True Story of Jesse James (1957), Hilda Crane (1956), The View (1964), Shock Corridor (1963), "The Virginian" (1962), "The from Pompey's Head (1955), Broken Lance (1954), Hell and High Dick Powell Show" (1962), Merrill's Marauders (1962), Water (1954), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Pickup on Underworld U.S.A. (1961), The Crimson Kimono (1959), South Street (1953), Titanic (1953), Niagara (1953), What Price Verboten! (1959), Forty Guns (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), Glory (1952), O. Henry's Full House (1952), Viva Zapata! (1952), China Gate (1957), House of Bamboo (1955), Hell and High Panic in the Streets (1950), Pinky (1949), It Happens Every Water (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Park Row (1952), Spring (1949), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Yellow Sky Fixed Bayonets! (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951), The Baron of (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), Call Northside 777 Arizona (1950), and I Shot Jesse James (1949). -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q89f608 Author Boman, James Stephan Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Studies by James Stephan Boman Committee in charge: Professor Janet Walker, Chair Professor Charles Wolfe Professor Peter Bloom Professor Colin Gardner September 2019 The dissertation of James Stephan Boman is approved. ___________________________________________________ Peter Bloom ___________________________________________________ Charles Wolfe ___________________________________________________ Colin Gardner ___________________________________________________ Janet Walker, Committee Chair March 2019 Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography Copyright © 2019 By James Stephan Boman iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my friends and colleagues at UC Santa Barbara, including the fellow members of my cohort—Alex Champlin, Wesley Jacks, Jennifer Hessler, and Thong Winh—as well as Rachel Fabian, with whom I shared work during our prospectus seminar. I would also like to acknowledge the diverse and outstanding faculty members with whom I had the pleasure to work as a student at UCSB, including Lisa Parks, Michael Curtin, Greg Siegel, and the rest of the faculty. Anna Brusutti was also very important to my development as a teacher. Ross Melnick has been a source of unflagging encouragement and a fount of advice in my evolution within and beyond graduate school. -

Revue De Recherche En Civilisation Américaine, 6

Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine 6 | 2016 Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations Women and Comics, Authorships and Representations Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 ISSN : 2101-048X Éditeur David Diallo Référence électronique Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016, « Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 19 décembre 2016, consulté le 16 mars 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 mars 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Editorial Amélie Junqua et Céline Mansanti Women Comics Authors in France and Belgium Before the 1970s: Making Them Invisible Jessica Kohn L’autoreprésentation féminine dans la bande dessinée pornographique Irène Le Roy Ladurie Empowered et le pouvoir du fan service Alexandra Aïn Women W.a.R.P.ing Gender in Comics: Wendy Pini’s Elfquest as mixed power fantasy Isabelle L. Guillaume A 21st Century British Comics Community that Ensures Gender Balance Nicola Streeten Hors thème Book review Sabbagh, Daniel. L’égalité par le droit, les paradoxes de la discrimination positive aux Etats- Unis Paris, Economica, collection « Etudes Politiques », 2003 [2007], 458 p. Laure Gillot-Assayag Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016 2 Editorial Amélie Junqua and Céline Mansanti 1 Aux Etats-Unis, les utilisatrices de Facebook représentent aujourd’hui 53% des utilisateurs de Facebook qui lisent de la bande dessinée, 40% de plus qu’il y a trois ans. Pourtant, moins de 30% des personnages et des écrivains de BD sont des femmes, même si ces chiffres progressent également (http://www.ozy.com/acumen/the-rise-of-the- woman-comic-buyer/63314). -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

The Mexican Film Bulletin Special Issue: Summer 2020

THE MEXICAN FILM BULLETIN SUMMER 2020 ISSUE TThhee MMeexxiiccaann FF iillmm BBuulllleettiinn SSppeecciiaall IIssssuuee:: SS uummmmeerr 22002200 We're Back! (Sort Of) years of age. Óscar Chávez Fernández was born in Although at this point we're not ready to resume March 1935 in Mexico City. Chávez became "regular" publication, there will hopefully be two interested in acting, studying with Seki Sano and at the special issues of MFB in 2020, one in the summer and Instituto de Bellas Artes school. He also worked in our annual "Halloween Issue" at the end of October. radio, sang, and directed plays before making his Sadly, a number of film personnel have passed screen debut in Los away since our last issue (December 2019) and so we caifanes (1966). have a lot of obituaries this time. A number of these Chávez subsequently individuals are from a certain "generation" who began appeared in a number their film work in the 1960s or early 1970s-- Jaime of popular films, Humberto Hermosillo, Gabriel Retes, Pilar Pellicer, including the remake Aarón Hernán, Óscar Chávez, Héctor Ortega--and thus of Santa, but spent made films that are particularly well-remembered by much of his time on those of a certain age (like yours truly). [It also means music, along with that two or more of these people often worked on the political and social same film, as some of the reviews in this issue activism. In the mid- illustrate.] 1970s he was among The COVID-19 pandemic has strongly affected film the actors who formed the Sindicato de Actores and other entertainment industries. -

Filmography 1963 Through 2018 Greg Macgillivray (Right) with His Friend and Filmmaking Partner of Eleven Years, Jim Freeman in 1976

MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography 1963 through 2018 Greg MacGillivray (right) with his friend and filmmaking partner of eleven years, Jim Freeman in 1976. The two made their first IMAX Theatre film together, the seminal To Fly!, which premiered at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum on July 1, 1976, one day after Jim’s untimely death in a helicopter crash. “Jim and I cared only that a film be beautiful and expressive, not that it make a lot of money. But in the end the films did make a profit because they were unique, which expanded the audience by a factor of five.” —Greg MacGillivray 2 MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography Greg MacGillivray: Cinema’s First Billion Dollar Box Office Documentarian he billion dollar box office benchmark was never on Greg MacGillivray’s bucket list, in fact he describes being “a little embarrassed about it,” but even the entertainment industry’s trade journal TDaily Variety found the achievement worth a six-page spread late last summer. As the first documentary filmmaker to earn $1 billion in worldwide ticket sales, giant-screen film producer/director Greg MacGillivray joined an elite club—approximately 100 filmmakers—who have attained this level of success. Daily Variety’s Iain Blair writes, “The film business is full of showy sprinters: filmmakers and movies that flash by as they ring up impressive box office numbers, only to leave little of substance in their wake. Then there are the dedicated long-distance specialists, like Greg MacGillivray, whose thought-provoking documentaries —including EVEREST, TO THE ARCTIC, TO FLY! and THE LIVING Sea—play for years, even decades at a time. -

The New School, Everybody Comes to Rick's

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model or to indicate particular areas that are of interest to the Endowment, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects his or her unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at https://www.neh.gov/grants/research/public- scholar-program for instructions. Formatting requirements, including page limits, may have changed since this application was submitted. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Everybody Comes to Rick’s: How “Casablanca” Taught Us to Love Movies Institution: The New School Project Director: Noah Isenberg Grant Program: Public Scholar Program 400 Seventh Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Everybody Comes to Rick’s: How Casablanca Taught Us to Love Movies On Thanksgiving Day 1942, the lucky ticket holders who filled the vast, opulent 1,600-seat auditorium at Warner Brothers’ Hollywood Theatre in midtown Manhattan—where today the Times Square Church stands—were treated to the world premiere of Casablanca, the studio’s highly anticipated wartime drama. -

Film Essay for "This Is Cinerama"

This Is Cinerama By Kyle Westphal “The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stage play, nor is it a feature picture not a travelogue nor a symphonic concert or an opera—but it is a combination of all of them.” So intones Lowell Thomas before introduc- ing America to a ‘major event in the history of entertainment’ in the eponymous “This Is Cinerama.” Let’s be clear: this is a hyperbol- ic film, striving for the awe and majesty of a baseball game, a fireworks show, and the virgin birth all rolled into one, delivered with Cinerama gave audiences the feeling they were riding the roller coaster the insistent hectoring of a hypnotically ef- at Rockaway’s Playland. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. fective multilevel marketing pitch. rama productions for a year or two. Retrofitting existing “This Is Cinerama” possesses more bluster than a politi- theaters with Cinerama equipment was an enormously cian on the stump, but the Cinerama system was a genu- expensive proposition—and the costs didn’t end with in- inely groundbreaking development in the history of motion stallation. With very high fixed labor costs (the Broadway picture exhibition. Developed by inventor Fred Waller from employed no less than seventeen union projectionists), an his earlier Vitarama, a multi-projector system used primari- unusually large portion of a Cinerama theater’s weekly ly for artillery training during World War II, Cinerama gross went back into the venue’s operating costs, leaving sought to scrap most of the uniform projection standards precious little for the producers. -

Finding Neverland

BARRIE AND THE BOYS 0. BARRIE AND THE BOYS - Story Preface 1. J.M. BARRIE - EARLY LIFE 2. MARY ANSELL BARRIE 3. SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES 4. PETER PAN IS BORN 5. OPENING NIGHT 6. TRAGEDY STRIKES 7. BARRIE AND THE BOYS 8. CHARLES FROHMAN 9. SCENES FROM LIFE 10. THE REST OF THE STORY Barrie and the Llewelyn-Davies boys visited Scourie Lodge, Sutherland—in northwestern Scotland—during August of 1911. In this group image we see Barrie with four of the boys together with their hostess. In the back row: George Llewelyn Davies (age 18), the Duchess of Sutherland and Peter Llewelyn Davies (age 14). In the front row: Nico Llewelyn Davies (age 7), J. M. Barrie (age 51) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (age 11). Online via Andrew Birkin and his J.M. Barrie website. After their mother's death, the five Llewelyn-Davies boys were alone. Who would take them in? Be a parent to them? Provide for their financial needs? Neither side of the family was really able to help. In 1976, Nico recalled the relief with which his uncles and aunts greeted Barrie's offer of assistance: ...none of them [the children's uncles and aunts] could really do anything approaching the amount that this little Scots wizard could do round the corner. He'd got more money than any of us and he's an awfully nice little man. He's a kind man. They all liked him a good deal. And he quite clearly had adored both my father and mother and was very fond of us boys.