A Tale of Two Brighids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

Pilgrimage Stories: the Farmer Fairy's Stone

PILGRIMAGE STORIES: THE FARMER FAIRY’S STONE By Betty Lou Chaika One of the primary intentions of our recent six-week pilgrimage, first to Scotland and then to Ireland, was to visit EarthSpirit sanctuaries in these ensouled landscapes. We hoped to find portals to the Otherworld in order to contact renewing, healing, transformative energies for us all, and especially for some friends with cancer. I wanted to learn how to enter the field of divinity, the aliveness of the EarthSpirit world’s interpenetrating energies, with awareness and respect. Interested in both geology and in our ancestors’ spiritual relationship with Rock, I knew this quest would involve a deeper meeting with rock beings in their many forms. When we arrived at a stone circle in southwest Ireland (whose Gaelic name means Edges of the Field) we were moved by the familiar experience of seeing that the circle overlooks a vast, beautiful landscape. Most stone circles seem to be in places of expansive power, part of a whole sacred landscape. To the north were the lovely Paps of Anu, the pair of breast-shaped hills, both over 2,000 feet high, named after Anu/Aine, the primary local fertility goddess of the region, or after Anu/Danu, ancient mother goddess of the supernatural beings, the Tuatha De Danann. The summits of both hills have Neolithic cairns, which look exactly like erect nipples. This c. 1500 BC stone circle would have drawn upon the power of the still-pervasive earlier mythology of the land as the Mother’s body. But today the tops of the hills were veiled in low, milky clouds, and we could only long for them to be revealed. -

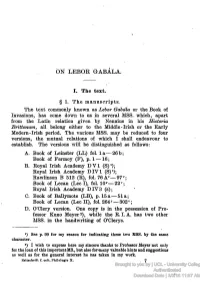

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

BRT Past Schedule 2016

Join Our Mailing List! 2016 Schedule current schedule 2015 past schedule 2014 past schedule 2013 past schedule 2012 past schedule 2011 past schedule 2010 past schedule 2009 past schedule JANUARY 2016 NOTE: If a show at BRT has an advance price & a day-of-show price it means: If you pre-pay OR call in your reservation any time before the show date, you get the advance price. If you show up at the door with no reservations OR call in your reservations on the day of the show, you will pay the day of show price. TO MAKE RESERVATIONS, CALL BRT AT: 401-725-9272 Leave your name, number of tickets desired, for which show, your phone number and please let us know if you would like a confirmation phone call. Mondays in January starting Jan. 4, $5.00 per class, 6:30-7:30 PM ZUMBA CLASSES WITH APRIL HILLIKER Thursday, January 7 5:00-6:00 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog 'NOG' TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins 6:00-7:00 PM: 8-week class SOFT SHOE TECHNIQUE with Erika Damiani begins 7:00-8:00 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog GREEN TROUPE (performance troupe) with Erika Damiani begins Friday, January 8 4:30-5:30 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog RINCE TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins 5:30-6:30 PM: 8-week class BEGINNER/ADVANCED BEGINNER HARD SHOE with Erika Damiani begins 6:30-7:30 PM: 8-week class SOFT SHOE TECHNIQUE with Erika Damiani begins 7:30-8:30 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog CEOL TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins Saturday, January 9 9:00 AM: 8-week class in BEGINNER IRISH STEP DANCE for children 5-10 with Erika Damiani begins 10:00 AM: 8-week class in CONTINUING -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Irish Folklore and Mythology in Irish Young Adult Fantasy Literature: Kate Thompson’s The New Policeman, and O.R. Melling’s The Hunter’s Moon.“ Verfasserin Monika Kraigher angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, im Januar 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Franz Wöhrer To my grandmother, for her love, guidance and support... I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Wöhrer for his exceptional guidance and patience. Thank you to my mother who has supported and motivated me unconditionally during my studies and in my everyday life. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and colleagues, notably the “gang“ from the Australian literature room, who were a great mental support during the work on this diploma thesis. DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I confirm to have conceived and written this Diploma Thesis in English all by myself: Quotations from other authors are all clearly marked and acknowledged in the bibliographical references, either in the footnotes or within the text. Any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the works of other authors are truthfully acknowledged and identified in the footnotes. Table of contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Irish Children’s and Young Adult Literature ........................................................ -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 6

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 6 Introduction Welcome to the sixth lesson. What a fantastic achievement making it so far. If you are enjoying the lessons let like-minded friends know. In this lesson, we are looking at the diet, clothing, and appearance of the Celts. We are also going to look at the complex social structure of the wolves and dispel some common notions about Alpha, Beta and Omega wolves. In the Bards section we look at the tales associated with Lugh. We will look at the role of Vates as healers, the herbal medicinal gardens and some ancient remedies that still work today. Finally, we finish the lesson with an overview of the Brehon Law of the Druids. I hope that there is something in the lesson that appeals to you. Sometimes head knowledge is great for General Knowledge quizzes, but the best way to learn is to get involved. Try some of the ancient remedies, eat some of the recipes, draw principles from the social structure of wolves and Brehon law and you may even want to dress and wear your hair like a Celt. Blessings to you all. Filtiarn Celts The Celtic Diet Athenaeus was an ethnic Greek and seems to have been a native of Naucrautis, Egypt. Although the dates of his birth and death have been lost, he seems to have been active in the late second and early third centuries of the common era. His surviving work The Deipnosophists (Dinner-table Philosophers) is a fifteen-volume text focusing on dining customs and surrounding rituals. -

Paganism Is a Group of Religions That Includes, Wiccans, Druids, Heathens and Others.1 They Share a Common Reverence for the Earth

PaganPaganiiiissssmmmm Paganism is a group of religions that includes, Wiccans, Druids, Heathens and others.1 They share a common reverence for the Earth. Some see it as a living system to be taken care of; some see it as a living deity to be worshiped; some see it as Mother-Earth who provides and cares for her children; some see it as a combination of all three. Most strands of Paganism are rooted in European folklore, though some take their inspiration from North American, African, or other cultures. All claim to predate Christianity. It is estimated that there are over 250,000 Pagans in the British Isles today. God Pagans worship the divine in many different forms, both male and female. The most important and widely recognised are the God and Goddess (or Gods and Goddesses) whose annual cycle of giving birth and dying defines the Pagan year. Pagans can be pantheists, polytheists, duotheists, or monists. Most acknowledge the existence of Nature spirits — river spirits, dryads, elves, pixies, fairies, gnomes, goblins and trolls — and ancestral spirits and often engage with them in prayer. Some do not believe in deities at all but simply revere Nature. Creation The aim of Pagan ritual is to make contact with the divine in the world that surrounds us. Pagans are deeply aware of the natural world and see the power of the divine in the ongoing cycle of life and death. Pagans are, understandably, concerned about the environment — most try to live so as to minimise harm to it — and about the preservation of ancient sites of worship. -

Ogma's Tale: the Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius

Ogma’s Tale: The Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius Presented to Whispering Lake Grove for Samhain, October 30, 2016 by Nathan Large A tale you’ve asked, and a tale you shall have, of the Dagda and his envoy to the Morrigan. I’ve been tasked with the telling: lore-keeper of the Tuatha de Danann, champion to two kings, brother to the Good God, and as tied up in the tale as any… Ogma am I, this Samhain night. It was on a day just before Samhain that my brother and the dark queen met, he on his duties to our king, Nuada, and Lugh his battle master (and our half-brother besides). But before I come to that, let me set the stage. The Fomorians were a torment upon Eireann and a misery to we Tuatha, despite our past victory over the Fir Bolg. Though we gained three-quarters of Eireann at that first battle of Maige Tuireadh, we did not cast off the Fomor who oppressed the land. Worse, we also lost our king, Nuada, when the loss of his hand disqualified him from ruling. Instead, we accepted the rule of the half-Fomorian king, Bres, through whom the Fomorians exerted their control. Bres ruined the court of the Tuatha, stilling its songs, emptying its tables, and banning all competitions of skill. None of the court could perform their duties. I alone was permitted to serve, and that only to haul firewood for the hearth at Tara. Our first rejection of the Fomor was to unseat Bres, once Nuada was whole again, his hand restored. -

An Introduction to Brigid Orlagh Costello What Will We Cover?

An Introduction to Brigid Orlagh Costello What will we cover? Pronunciation & spelling Who is Brigid? Practices and customs Practical Exercise Personal gnosis and practices Pronunciation and spelling Brig Bric Brigid Brigit Brighid Bríd Bridget Who is Brigid? Family Tree Cath Maige Tuired Cormac’s Glossary, Daughter(s) of the Dagda The Law Givers The Saint, the Abbess, the Christian times Personal gnosis and practices Family tree Daughter(s) of the Dagda No mother!! Brothers: Aengus Óg, Aed, Cermait Ruadán (Bres’ son, half Formorian, Caith Maigh Tuired) Sons of Tuireann (Brian, Iuchar and Iucharba) Cath Maige Tuired Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Mag Tuired (Author:[unknown]) section 125 But after the spear had been given to him, Rúadán turned and wounded Goibniu. He pulled out the spear and hurled it at Rúadán so that it went through him; and he died in his father's presence in the Fomorian assembly. Bríg came and keened for her son. At first she shrieked, in the end she wept. Then for the first time weeping and shrieking were heard in Ireland. (Now she is the Bríg who invented a whistle for signalling at night.) Caith Maige Tuired Communication Grief Mother Daughter(s) of the Dagda “Brigit the poetess, daughter of the Dagda, she had Fe and Men, the two royal oxen, from whom Femen is named. She had Triath, king of her boars, from whom Treithirne is named. With them were, and were heard, the three demoniac shouts after rapine in Ireland, whistling and weeping and lamentation.” (source: Macalister, LGE, Vol. 4, p. -

January 2019

published since 1948 for the town of Glen Echo, Maryland ≈ chartered in 1904 ≈January 2019 playing, etc. She will come since that will have the most Town Council Notes to a Town Council meeting impact on residents. The once the inventory is com- first house to be built will be he Town Council meeting was held December 10 with plete. For now, she continues on the lot facing upper Cor- Members Costello, Spealman, and Stiglitz present, to tackle the files in Town nell Avenue. Welty Homes Talong with the Mayor, Town Manager, and four residents. Hall, which are in a “signifi- will be the homebuilders as cant state of disarray.” well as the contractors for Town Business for Town Hall, the ADA- Ms. Ventura and the Echo the road project. Town Manager Nicole Ven- compliant elevator hasn’t editors are working on a The owner of 7315 Uni- tura told the Council that worked in a while and is pamphlet for new residents, versity Avenue had until going forward the Irish Inn awaiting a part to be fixed. which explains Town gov- December 16 to appeal the would be billed quarterly Modernizing the elevator ernment and services. Once County’s ruling that wall- for the Town land they use could cost a lot ($50k), so it is complete, all residents ing in the back porch and for parking, and payment Ms. Ventura and the Mayor will receive a copy. expanding the kitchen has been received. It was are also looking into a chair without permitting was also mentioned that a new elevator, which would go up Building and unacceptable.