Petrol Sniffing in Remote Northern Territory Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001–02 Annual Report

community COOPERATIVE RESEARCH CENTRE partnerships FOR ABORIGINAL & TROPICAL HEALTH action research 2001–02 Annual Report cooperative links strategic research Indigenous education ESTABLISHED AND SUPPORTED UNDER THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT’S COOPERATIVE RESEARCH CENTRES PROGRAM MISSION STATEMENT The Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal To provide a cross-cultural framework for and Tropical Health (CRCATH) is a ‘public strategic research, leading to evidence-based good’ centre, funded mainly through the improvements in education and health practice, a Commonwealth Government’s Cooperative more highly-skilled health workforce, more Research Centres program. The CRCATH has effective health services, and reconciliation brought together organisations engaged in between Aboriginal and Western perspectives on health service delivery and research expertise health. into an unincorporated joint venture. The objectives of the Cooperative Research Funding and in-kind support are provided Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health are to: through the six core partners: ❚ Carry out and promote research to find new Central Australian Aboriginal Congress knowledge that will help to improve the health Danila Dilba Biluru Butji Binnilutlum Health of all Aboriginal people and of other people Service Aboriginal Corporation living in tropical regions. Flinders University of South Australia ❚ Carry out and promote research, education Menzies School of Health Research and training leading to improved and Northern Territory University practical means for improving Aboriginal Department of Health and Community Services health by means which are both feasible and Menzies School of Health Research is also the effective. Centre host, and provides Centre Agent services ❚ Increase the skills of Aboriginal people, and and accommodation for the secretariat and to encourage training and employment executive of the CRCATH. -

Members of the Legislative Assembly 1

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 1st Assembly 1974 to 13th Assembly Current As at 29 February 2020 1 MEMBERS OF THE 1ST ASSEMBLY Elected on 19 October 1974 to 12 August 1977 MEMBER DIVISION FROM TO PARTY REMARKS Bernard Francis Kilgariff Alice Springs 19.10.74 12.11.75 CLP Speaker George Eric Manuell Alice Springs 07.02.76 12.08.77 CLP By-election Rupert James Kentish Arnhem 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Ian Lindsay Tuxworth Barkly 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Nicholas Manuel Dondas Casuarina 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP John Leslie Stuart Elsey 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Speaker MacFarlane Grant Ernest Tambling Fannie Bay 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP James Murray Robertson Gillen 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Paul Anthony Edward Jingili 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Everingham Roger Michael Steele Ludmilla 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP David Lloyd Pollock Macdonnell 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Roger Ryan Millner 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Alline Dawn Lawrie Nightcliff 19.10.74 12.08.77 IND Milton James Ballantyne Nhulunbuy 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Ronald John Withnall Port Darwin 19.10.74 12.08.77 IND Elizabeth Jean Andrew Sanderson 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Roger William Stanley Stuart 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Vale Marshall Bruce Perron Stuart Park 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Hyacinth Tungutalum Tiwi 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Godfrey (Goff) Alan Letts Victoria River 19.10.74 12.08.77 CLP Majority Leader PROROGATION The Legislative Assembly was prorogued by His Honour the Administrator as follows: I, JOHN ARMSTRONG ENGLAND, the Administrator of the Northern Territory of Australia, in pursuance of section 22(1) of the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978 of the Commonwealth, by this notice prorogue the Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory of Australia. -

2008 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 9 August 2008

2008 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 9 August 2008 CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election ............................................................... 3 Legislative Assembly Results by Electoral Division.................................................... 6 By-elections 2005-2008 ........................................................................................... 10 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Results ............................................................... 11 Regional Summaries ............................................................................................... 14 Members Elected .................................................................................................... 16 Symbols .. Nil or rounded to zero * Sitting MPs .… „Ghost‟ candidate, where a party contesting the previous election did not nominate for the current election Party Abbreviations (blank) Non-affiliated candidates CLP Country Liberal Party GRN Green IND Independent LAB Territory Labor OTH Others Relevant dates Issue of Writ Tuesday 22 July 2008 Close of Electoral Roll 8pm Thursday 24 July 2008 Close of Nominations 12 noon Monday 28 July 2008 Commencement of Mobile and Postal voting Thursday 31 July 2008 Polling Day Saturday 9 August 2008 Close of Receipt for Postal Votes 6pm Friday 15 August 2008 Declaration of Polls 10am Monday 18 August 2008 Return -

Inspirational Old Girl, Sarah Thomson (Class of 2005)

VOL. 18 | 2020 17 Graham Street, South Brisbane Qld 4101 PO Box 3357, South Brisbane Qld 4101 P 07 3248 9200 | somerville.qld.edu.au A school of the Presbyterian and Methodist Schools Association. The PMSA is a mission of the Presbyterian and Uniting Churches. CRICOS Provider Number: 00522G VOL. 18 | 2020 Inspirational Old Girl, Sarah Thomson (Class of 2005). Join us on our new OGA Portal! Never has there been a better time to stay connected Visit somervillehouseoga. com.au/signup to with your fellow Somerville House Old Girls. Whether become an OGA member. If you are an existing you are a member of the OGA or not check out what is OGA member you will need to activate your online going on via somervillehouseoga. com.au. There is a profile to access these benefits. We can help you wealth of information freely available including hundreds with this if you don’t feel very tech savvy – reach of news article and updates on Old Girls. Within our OGA out via connect@ somervillehouseoga. com. au Contentswebsite we also host a member’s only portal providing or check out the online help guide via exclusive access to: somervillehouseoga. com. au/ page/ help. • Social Networking - Search the Members’ Directory The more up-to-date your profile is, the more benefit you will gain from the portal. Syncing your OGA profile 2 IN• PRINCIPALProfessional Networking – Search the OGA 24 CHASING GOLD to your LinkedIn account is an easy way to update 4 PITCHING THE AUSTRALIAN DREAM 25 FROM THE CLASSROOM TO THE COURT • Promote your OG Business 6 ISABEL BAUER – A LEGENDARY OLD GIRL 26 Looking CONGRATULATIONS after each other has never been more • Event photo gallery AND OGA LEGEND important and our connections are crucial. -

Annual Report 2011/2012

AnnuAl RepoRt 2011/2012 Royal Life Saving Society - Australia is dedicated to turning everyday people into everyday community lifesavers. www.royallifesaving.com.au 1 About RoyAl life SAving Royal Life Saving is focused on reducing drowning and promoting healthy, active and skilled communities through innovative, reliable, evidence based advocacy; strong and effective partnerships, quality programs, products and services; underpinned by a cohesive and sustainable national organisation. Royal Life Saving is a public benevolent institution (PBI) dedicated to reducing drowning and turning everyday people into everyday community lifesavers. We achieve this through: • Advocacy • Education • Training • Health Promotion • Aquatic Risk Management • Community Development • Research • Sport, Leadership and Participation • International Networks We are guided by the values of: Safety, Quality, Integrity and the Humanitarian tradition and have been serving the Australian community for over 118 years. Royal Life Saving Society – Australia is a Public Company Limited by Guarantee. ABN: 71 008 594 616 www.royallifesaving.com.au 2 AnnuAl RepoRt 2011/2012 11 CONTENTS Patrons, Directors, Office Bearers and Committees 4 International Life Saving Organisations 4 20 Life Members 5 In Memoriam 5 National President’s Report 6 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 7 Chief Operating Officer’s Report 8 Strategic Framework 2012–15 9 Financial Summary 10 National Operations Advocacy 11 Education 16 Training 20 Health Promotion 25 Aquatic Risk Management 28 Community Development -

2012 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 25 August 2012

2012 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 25 August 2012 CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election ............................................................... 3 Legislative Assembly Results by Electoral Division.................................................... 6 By-elections 2008-2012 ........................................................................................... 10 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Results ............................................................... 11 Regional Summaries ............................................................................................... 14 Symbols .. Nil or rounded to zero * Sitting MPs .… ‘Ghost’ candidate, where a party contesting the previous election did not nominate for the current election (n.a.) Not available Party Abbreviations - Non-affiliated candidates ASXP Australian Sex Party CLP Country Liberal Party FNP First Nation's Party GRN Green IND Independent LAB Territory Labor OTH Others Relevant dates Issue of Writ Monday 6 August 2012 Close of Electoral Roll 8pm Wednesday 8 August 2012 Close of Nominations 12 noon Friday 10 August 2012 Polling Day Saturday 25 August 2012 Declaration of Poll and Return of Writ Monday 3 September 2012 Late Date for Return of Writ Friday 28 September 2012 2 Antony Green – ABC Election Unit – July 2016 2012 Northern Territory Election INTRODUCTION This paper contains -

Tabled Papers Index

Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Tabled Papers — Eleventh Assembly (2008-2012) Tabled INDEX This document allows users to search all papers tabled during the life of the Eleventh Assembly. To access a document, use the Tabled Paper number appearing in the first column of the Index (eg —0001 or 1257). Please note that we are working backwards to digitise our older records and they will be uploaded as they are completed for the previous Assemblies. Should you require a Tabled Paper from a previous Assembly you can contact the Table Office by email on [email protected] Tabled Papers are all documents tabled in the Assembly, including but not limited to: Messages from the Administrator Administrative Arrangements Orders Papers tabled by Members during Assembly debates Explanatory Statements accompanying bills introduced Petitions Warrants Reports on Members’ travel Committee Reports Papers tabled at Estimates Committee hearings Annual reports required by NT and some Commonwealth statutes Coroner’s reports Subordinate legislation Reports to the Assembly from Officers of the Assembly (Ombudsman, Auditor- General, Electoral Commission) Please contact the Table Office if you have any questions on 8946 1447 or 8946 1452. Eleventh Assembly - Tabled Papers - page 1 No Description Tabled by Date 1 Letter, Resignation of Mrs Fay Miller, Member for Katherine dated 21 July 2008 Speaker 09.09.08 2 Letter from Mr Tom Pauling AO, QC to Speaker, Hon. J. Aagaard, Proroguing the Deemed 09.09.08 Legislative Assembly dated -

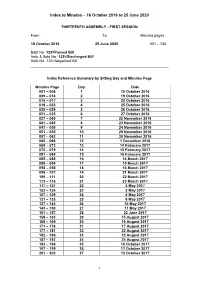

Consolidated Index to Minutes of Proceedings

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 25 June 2020 001 – 746 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 – 008 1 18 October 2016 009 – 014 2 19 October 2016 015 – 017 3 20 October 2016 019 – 023 4 25 October 2016 025 – 029 5 26 October 2016 031 – 035 6 27 October 2016 037 – 040 7 22 November 2016 041 – 045 8 23 November 2016 047 – 050 9 24 November 2016 051 – 055 10 29 November 2016 057 – 063 11 30 November 2016 065 – 068 12 1 December 2016 069 – 073 13 14 February 2017 075 – 079 14 15 February 2017 081 – 084 15 16 February 2017 085 – 088 16 14 March 2017 089 – 094 17 15 March 2017 095 – 098 18 16 March 2017 099 – 107 19 21 March 2017 109 – 111 20 22 March 2017 113 – 116 21 23 March 2017 117 – 121 22 2 May 2017 123 – 126 23 3 May 2017 127 – 129 24 4 May 2017 131 – 135 25 9 May 2017 137 – 142 26 10 May 2017 143 – 150 27 11 May 2017 151 – 157 28 22 June 2017 159 – 163 29 15 August 2017 165 – 169 30 16 August 2017 171 – 176 31 17 August 2017 177 – 181 32 22 August 2017 183 – 186 33 23 August 2017 187 – 192 34 24 August 2017 193 – 196 35 10 October 2017 197 – 199 36 11 October 2017 201 – 203 37 12 October 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 205 – 208 38 17 October 2017 209 – 213 39 18 October 2017 215 – 220 40 19 October 2017 221 – 225 41 21 November 2017 227 – 233 42 22 November 2017 235 – 247 43 23 November -

Hon Kezia Purick MLA, Speaker

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY The Calm after the Storm – Are Storm Clouds Brewing Again? The Hon Kezia Purick MLA, Speaker As the Northern Territory reaches its midterm mark, two years after the 2016 election and two years before the 2020 General Election, it is timely to pause and assess how orderly the 13 th Assembly is and consider comparisons with the 12 th and previous Assemblies to consider which was the most tumultuous in the short and colourful history of the Northern Territory legislature. The 12 th Assembly ran from 2012 to 2016 and had what would kindly be referred to as some big personalities . At least six Ministers in the Cabinet (unofficially) actively wanted the role of Chief Minister for themselves with three Ministers serving or attempting to serve in the top job. I won’t go into detail here about the bizarre midnight coup of 3 February 2015, just enter that into your favourite search engine for more details. A revolving door of Cabinet reshuffles (18 in four years) and the sheer number of Deputy Chief Ministers reflected the lack of consistent leadership in Government. This had a significant impact upon the Legislative Assembly. A Government with initially 16 Members in August 2016 was reduced to a perilous minority of 11 by the time of the 2016 election. With a new Assembly came renewal. We have not even had a Cabinet reshuffle since the first Ministry was announced after the 2016 election. The Country Liberals were soundly defeated in 2016 with only two Members being returned to a shrunken Opposition bench and 18 Labor Government Members now occupying the Treasury benches in the 25 Member parliament. -

02.11 ASC Minutes

CONTENTS Page Minute PRESENT 1 WORSHIP 1 WELCOMES 1 APOLOGIES 1 RECOGNITION OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS OF THE LAND 1 PASTORAL MATTERS 1 THANKYOU TO GILLIAN STONE 2 APPROVAL OF TIMETABLE AND AGENDA 2 02.54 CONFIRMATION OF THE MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING 2 02.55 NOTE CONSTITUTION CLAUSE 39 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2 02.56 SYNOD SHARING – SYNOD OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 3 BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE PREVIOUS STANDING COMMITTEE 1. Coolamon College (ASC Minute 02.37) 3 02.57 2. Task Group on Governance (ASC Minute 02.40) 3 02.58 3. Agency Arrangements (ASC Minute 02.41) 4 02.59 4. Review of National Director, Frontier Services and Associate General Secretary (ASC Minute 02.45.02(b) – (c)) (a) National Director, Frontier Services 4 02.60 (b) Associate General Secretary 4 02.61 5. Discussion on Membership (ASC Minute 02.46.04) 5 02.62 6. Report of Task Group on Theological Education (ASC Minute 02.49) 5 02.63 7. Requests to bless same sex relationships (ASC Minute 02.50.03) 5 02.64 8. Vilification and harassment (ASC Minute 02.52) 6 02.65 FROM ASSEMBLY BODIES 1. Tenth Assembly Design Team 6 02.66 2. Report re “Uniting in Worship #2” 6 02.67 3. Report of Ministry of Deacon Review Group 7 02.68 4. Unity & International Mission / Uniting Church Overseas Aid 7 02.69 5. National Co-operation 7 02.70 6. General report 8 02.71 7. Report on the National Covenanting Summit 9 02.72 Minutes of Assembly Standing Committee 15 – 17 November 2002 Seeking a Heart of Wisdom (Guidelines for Continuing 1 Attachment B Education for Uniting Church Ministers) 8. -

Representation of Women in Australian Parliaments

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services BACKGROUND NOTE 7 March 2012 Representation of women in Australian parliaments Dr Joy McCann and Janet Wilson Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 How does Australia rate? ......................................................................................................................... 2 Parliamentarians ................................................................................................................................. 2 Parliamentary leaders and presiding officers ..................................................................................... 3 Ministers and parliamentary secretaries ............................................................................................ 4 Women chairing parliamentary committees ...................................................................................... 6 Women candidates in Commonwealth elections ............................................................................... 7 Historical overview................................................................................................................................. 10 First women in parliament ................................................................................................................ 10 Commonwealth .......................................................................................................................... -

Theparliamentarian

TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2018 | Volume 99 | Issue Three | Price £14 3Ds: Democracy, Development and Diversity in the Commonwealth PAGES 166-171 PLUS The CPA and the New Parliament ‘High and exacting The role of Legislators rules-based Building opens in demands’ on the in tackling global international order Grenada Speaker orphanage trafficking PAGE 172 PAGE 181 PAGE 186 PAGE 219 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE CPA Parliamentary Fundamentals The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of Flagship Programme 2018 good governance, and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. NEWLY ELECTED OR RETURNING COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARIAN? Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed as of 10 August 2018 LOOKING TO STRENGTHEN YOUR KNOWLEDGE OF PARLIAMENTARY 2018 PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE? September If so, the CPA invites you to enrol on its new Parliamentary 4 to 7 September 54th General Meeting of the Society of Clerks-at-the-Table (SoCATT), Toronto, Canada Fundamentals Programme, with one additional course specifically 15 September International Day of Democracy (IDD) developed for CPA Small Branches. Programmes are accredited with McGill University, Canada (Small Branches programme) and the October University of Witwatersrand, South Africa (General programme). w/c 1 October CPA Fundamentals Programme (Online), University of Witwatersrand, South Africa Programme includes: Online modules | Residential components