A Case Study Analysis: How Sweet Briar College Prevailed Over Institutional Closure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

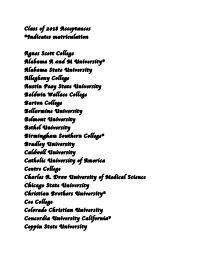

Class of 2018 Acceptances *Indicates Matriculation Agnes Scott

Class of 2018 Acceptances *Indicates matriculation Agnes Scott College Alabama A and M University* Alabama State University Allegheny College Austin Peay State University Baldwin Wallace College Barton College Bellarmine University Belmont University Bethel University Birmingham Southern College* Bradley University Caldwell University Catholic University of America Centre College Charles R. Drew University of Medical Science Chicago State University Christian Brothers University* Coe College Colorado Christian University Concordia University California* Coppin State University DePaul University Dillard University Eckerd College Fordham University Franklin and Marshall College Georgia State University Gordon College Hendrix College Hollins University Jackson State University Johnson C. Smith University Keiser University Langston University* Loyola College Loyola University- Chicago Loyola University- New Orleans Mary Baldwin University Middle Tennessee State University Millsaps College Mississippi State University* Mount Holyoke College Mount Saint Mary’s College Nova Southeastern University Ohio Wesleyan Oglethorpe University Philander Smith College Pratt Institute Ringling College or Art and Design Rollins College Rust College Salem College Savannah College or Art and Design Southeast Missouri State University Southwest Tennessee Community College* Spellman College Spring Hill College St. Louis University Stonehill College Talladega College Tennessee State University Texas Christian University Tuskegee University* University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Dayton University of Houston University of Kentucky University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa University of Memphis* University of Mississippi University of North Alabama University of Florida University of Southern Mississippi University of Tampa University of Tennessee Chattanooga* University of Tennessee Knoxville* University of Tennessee Marin Virginia State University Voorhees College Wake Forest University* Wiley College Xavier University, Louisiana Xavier University, Ohio . -

Agenda Book July 16, 2019

Agenda Book July 16, 2019 Location: New College Institute - Martinsville, VA July 2019 Agenda Book 1 July 16, 2019, Council Meetings Schedule of Events New College Institute 191 Fayette Street Martinsville, VA 24112 10:00 – 12:30 Academic Affairs Committee (Lecture Hall B) - Section A on the agenda (Committee members: Ken Ampy (chair), Rosa Atkins (vice chair), Gene Lockhart, Marianne Radcliff, Carlyle Ramsey, Katie Webb) 10:00 – 12:30 Resources and Planning Committee (Lecture Hall A) - Section B on the agenda (Committee members: Tom Slater (chair), Victoria Harker (vice chair), Marge Connelly, Henry Light, Stephen Moret, Bill Murray) 12:30 – 1:00 Brief Tour and Lunch 1:15 – 4:00 Council Meeting (Lecture Hall A) - Section C on the agenda NEXT MEETING: September 16-17 (University of Mary Washington). September 16 schedule will include meeting with public college presidents STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION FOR VIRGINIA July 2019 Agenda Book 2 Council meeting Time: July 16, 2019 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM EDT Location: New College Institute, 191 Fayette Street, Martinsville, VA 24112 Description: Academic Affairs and Resources and Planning Committee meetings Brief tour and lunch Council meeting Time Section Agenda Item Presenter Page --Cover sheet 1 --Meeting timeframes 2 --July 16 agendas 3 ACADEMIC AFFAIRS COMMITTEE A. (Lecture Hall B) 10:00 A1. --Call to Order Mr. Ampy 10:00 A2. --Approval of Minutes (May 20, 2019) Mr. Ampy 6 --Action on Programs at Public 10:05 A3. Dr. DeFilippo 11 Institutions --Update on Program Proposals in the 10:30 A4. Dr. DeFilippo 16 Review Pipeline --Action on Virginia Public Higher Education 11:00 A5. -

Binh Danh: Collecting Memories Has Been Supported by the Joan Danforth Art Museum Endowment

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: July 20, 2010 Lori Chinn Mills College Art Museum Program Manager 510.430.3340 or [email protected] Abby Lebbert Mills College Art Museum Publicity Assistant 510.430.2164 or [email protected] Mills College Art Museum Announces Exhibition of New Work by Bay Area Artist Binh Danh Oakland, CA—July 20, 2010. The Mills College Art Museum is pleased to announce a solo exhibition of new work by Bay Area artist Binh Danh entitled, Collecting Memories, featuring daguerreotypes, chlorophyll prints, photographs, and historical artifacts, which capture past and present memories of the American-Vietnam War. Collecting Memories is co-curated by Lori Chinn and Stephanie Hanor and will be on view from August 21 through December 12, 2010. An opening reception with the artist will take place on August 25 from 5:30–7:30 pm. Binh Danh collects photographs and other remnants of the American-Vietnam War and reprocesses and represents them in ways that bring new light to a complicated, multivalent history. Danh is known for his unique chlorophyll printing process in which he takes found portraits of war casualties and anonymous soldiers and transfers them onto leaves and grasses through the process of photosynthesis. While Danh left Vietnam with his family at a young age, return trips to the country have profoundly influenced the development of his work. Danh’s recent work uses a combination of found images from the American-Vietnam War and photographs taken by the artist on recent visits to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. “History is not something in the past. -

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards Full and complete nomination submissions must be received by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia no later than 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. Please direct questions and comments to: Ms. Ashley Lockhart, Coordinator for Academic Initiatives State Council of Higher Education for Virginia James Monroe Building, 10th floor 101 N. 14th St., Richmond, VA 23219 Telephone: 804-225-2627 Email: [email protected] Sponsored by Dominion Energy VIRGINIA OUTSTANDING FACULTY AWARDS To recognize excellence in teaching, research, and service among the faculties of Virginia’s public and private colleges and universities, the General Assembly, Governor, and State Council of Higher Education for Virginia established the Outstanding Faculty Awards program in 1986. Recipients of these annual awards are selected based upon nominees’ contributions to their students, academic disciplines, institutions, and communities. 2022 OVERVIEW The 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards are sponsored by the Dominion Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Dominion. Dominion’s support funds all aspects of the program, from the call for nominations through the award ceremony. The selection process will begin in October; recipients will be notified in early December. Deadline for submission is 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. The 2022 Outstanding Faculty Awards event is tentatively scheduled to be held in Richmond sometime in February or March 2022. Further details about the ceremony will be forthcoming. At the 2022 event, at least 12 awardees will be recognized. Included among the awardees will be two recipients recognized as early-career “Rising Stars.” At least one awardee will also be selected in each of four categories based on institutional type: research/doctoral institution, masters/comprehensive institution, baccalaureate institution, and two-year institution. -

WVWC Fact Book 2018-19

2018 West Virginia Wesleyan College Fact Book COMPILED BY OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH 0 Table of Contents Mission and Organizational Structure ........................................................................................................................................ 2 West Virginia Wesleyan College Statement of Mission .................................................................................................... 3 Wesleyan Accreditation ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Organizational Chart Fall 2018-19 .................................................................................................................................... 4 West Virginia Wesleyan College Administrative Execute Officers 2018-2019 ................................................................... 5 Administrative Executive Officers .................................................................................................................................... 5 Academic School Directors ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Fall 2018 New Students .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 First-time Full-time Freshmen Financial Aid Profile ....................................................................................................... -

BC Digital Commons Vol. 83, No. 1 | Fall 2007

Bridgewater College BC Digital Commons Bridgewater Magazine Journals and Campus Publications Fall 2007 Vol. 83, No. 1 | Fall 2007 Bridgewater College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bridgewater.edu/bridgewater_magazine gallery events SEPT. 3 -OCT.5 NOV.15 "Art and Society: Expressions on War,Prison 7:30 p.m. in Cole Hall ers, Materialism, and Politics"- Mixed-media Dr. Richard Wagner: Peace Psychology and its International works by Bridgewater Artist Robert Bersson. Aspects OCT.10-NOV.7 (Visit www.bridgewater.edu/convos for specifics.) Oct. 12: Reception in the Miller Gallery, 5-7 p.m. NOV.19 "BC Art Alumni:My First Ten Years"-BC Alums who 7:30 p.m. in Cole Half worked with Professor Michael Hough during his frst 10 Geraldine Kiefer:Virginia Byways,Panama Overlays:Trac years as an a rt profssor at Bridgewater. ings in a Traveled Landscape -Works in mixed drawing DEC.7 media on watercolor paper and in colored pencil over Kline Campus Center main lobby, 9 a.m.-3 p.m. photographs. Student Art Sale Kiefer is assistant professor of art history at Shenandoah NOV.12-DEC.14 University and an art historian with a Ph.D. from Case Western Nov. 19: Artist Talk, Cole Hall, 7:30 p.m. (see "Lecture" below); Reserve University. Reception in the Miller Gallery, 5-7 p.m. Information on the Winter/Spring Lectures will be listed on the "Nimrod Textures and Traces:The Venerable Tree and college Web site at www.bridgewater.edu/convos Smith Family Cemetery Series"- Photography and Draw ings by Shenandoah University Professor Geraldine Kiefer. -

Madhavi Kale EDUCATION 1992 Phd, University of Pennsylvania, Department of History 1989 MA, University of Pennsylvania, Departme

April 2021 Madhavi Kale EDUCATION 1992 PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Department of History 1989 MA, University of Pennsylvania, Department of History 1984 BA, Yale University, History EMPLOYMENT July 2016- Chair, Department of History, Bryn Mawr College July 2015- Professor of History, Bryn Mawr College July 2014-15 Chair, Department of Historical and Cultural Studies, University of Toronto Scarborough and Department of History July 2013-15 Department of Historical and Cultural Studies, University of Toronto Scarborough and Department of History, University of Toronto 2008- Professor of History, History Department, Bryn Mawr College 1999-2008 Associate Professor, History Department, Bryn Mawr College, Department chair January 2000-July 2004 and Acting Chair, January 2005-December 2006 1998-9 Coordinator, Haverford and Bryn Mawr Colleges' Bi-College Program in Feminist and Gender Studies 1992-9 Assistant Professor of History, Bryn Mawr College 1984-6 Assistant Program Coordinator for Women-in-Development projects, Save the Children (USA), Kathmandu, Nepal PUBLICATIONS Book 1998 Fragments of empire: capital, slavery, and Indian indentured labor (University of Pennsylvania Press) Articles 2020 “Wrestling with angels Theoretical Legacies of a Familiar Stranger,” History of the Present 10:1 (April 2020): pp. 122-128 2014 “Queering the Pitch from Beyond a Boundary,” Special Issue on Caribbean Historiography, Small Axe 43 (March 2014): 38-54 2013 “Response to the Forum,” on “Indian Ocean World as Method,” History Compass (July) vol 11 (7): pp. 531-35 April 2021 2007 “Diaspora of sub-continental Indians,” International Encyclopedia of the SocialSciences, 2nd Edition. “Race, Gender and the British Empire,” in Section V: Race, Class, Imperialism and Colonialism c1670-1969, Empire Online (London: Adam Matthew Publications). -

2017 18 Catalog

18 ◆ Catalog 2017 S MITH C OLLEGE 2 017–18 C ATALOG Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 S MITH C OLLEGE C ATALOG 2 0 1 7 -1 8 Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 413-584-2700 2 Contents Inquiries and Visits 4 Advanced Placement 36 How to Get to Smith 4 International Baccalaureate 36 Academic Calendar 5 Interview 37 The Mission of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance 37 History of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance for Medical Reasons 37 Accreditation 8 Transfer Admission 37 The William Allan Neilson Chair of Research 9 International Students 37 The Ruth and Clarence Kennedy Professorship in Renaissance Studies 10 Visiting Year Programs 37 The Academic Program 11 Readmission 37 Smith: A Liberal Arts College 11 Ada Comstock Scholars Program 37 The Curriculum 11 Academic Rules and Procedures 38 The Major 12 Requirements for the Degree 38 Departmental Honors 12 Academic Credit 40 The Minor 12 Academic Standing 41 Concentrations 12 Privacy and the Age of Majority 42 Student-Designed Interdepartmental Majors and Minors 13 Leaves, Withdrawal and Readmission 42 Five College Certificate Programs 13 Graduate and Special Programs 44 Advising 13 Admission 44 Academic Honor System 14 Residence Requirements 44 Special Programs 14 Leaves of Absence 44 Accelerated Course Program 14 Degree Programs 44 The Ada Comstock Scholars Program 14 Nondegree Studies 46 Community Auditing: Nonmatriculated Students 14 Housing and Health Services 46 Five College Interchange 14 Finances 47 Smith Scholars Program 14 Financial Assistance 47 Study Abroad Programs 14 Changes in Course Registration 47 Smith Programs Abroad 15 Policy Regarding Completion of Required Course Work 47 Smith Consortial and Approved Study Abroad 16 Directory 48 Off-Campus Study Programs in the U.S. -

Catalog 2008-2009

S w e et B riar College Catalog 2008-2009 2008-2009 College Calendar Fall Semester 2008 August 23, 2008 ____________________________________________ New students arrive August 27, 2008 __________________________________________ Opening Convocation August 28, 2008 _________________________________________________ Classes begin September 26, 2008 _____________________________________________ Founders’ Day September 25-27, 2008 ___________________________________Homecoming Weekend October 2-3, 2008 ________________________________________________ Reading Days October 17-19, 2008 __________________________________________ Families Weekend November 5, 2008 _____________________________ Registration for Spring Term Begins November 21, 2008 _________________________Thanksgiving vacation begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close November 22 at 8 a.m.) December 1, 2008_______________________________________________ Classes resume December 12, 2008________________________________________________ Classes End December 13, 2008________________________________________________Reading Day December 14-19, 2008 ____________________________________________ Examinations December 19, 2008_________________________________ Winter break begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close December 19 at 5:30 p.m.) Spring Semester 2009 January 21, 2009 ___________________________________________ Spring Term begins March 13, 2009 __________________________________ Spring vacation begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close March 14 at 8 a.m.) March 23, 2009 _________________________________________________ -

Forging a New Path

FORGING A NEW PATH, SWEET BRIAR TURNS TO THE FUTURE Dear Sweet Briar Alumnae, Throughout this spring semester, distinguished women musicians, writers and policy makers have streamed to the campus, in a series dubbed “At the Invitation of the President.” As you will read in this issue, the series started in January with a remarkable all-women ensemble of scholar-performers dedicated to excavating little-known string trios from the 17th and 18th century, and it ended the semester with a lecture by Bettina Ring, the secretary of agriculture and forestry for the Commonwealth. Sweet Briar was a working farm for most of its history, a fact that does not escape the secretary, both as an important legacy we share and cherish, but also as a resurgent possibility for the future — for Sweet Briar and Central Virginia. Through this series, one learns stunning things about women who shape history. A gradu- ate of Sweet Briar, Delia Taylor Sinkov ’34 was a top code breaker who supervised a group of women who worked silently — under an “omerta” never to be betrayed in one’s lifetime — to break the Japanese navy and army codes and eventually to help win the Battle of Midway. Ultimately, the number of code breakers surpassed 10,000. While America is a country that loves and shines light on its heroes, women have often stayed in the shadow of that gleaming light; they are history’s greatest omission. “Do you like doing the crossword puzzle?” Navy recruiters would ask the potential code breakers. “And are you engaged to be married?” If the answer to the former was a “yes” and to the lat- ter a “no,” then the women were recruited to the first wave of large-scale intelligence work upon which the nation would embark. -

Division of Professional Studies Spring 2021 Newsletter

Bridgewater College BC Digital Commons Division of Professional Studies Newsletters Division of Professional Studies Spring 2021 Division of Professional Studies Spring 2021 Newsletter Bridgewater College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bridgewater.edu/ professional_studies_newsletter DIVISION OF Economics and Business Administration PROFESSIONAL Health and Human Sciences Spring 2021 STUDIES Teacher Education Program Newsletter MESSAGE FROM THE BC SIGNS ARTICULATION DIVISION HEAD AGREEMENT IN COACHING I’ve spent most of my life being competi- tive, as anyone watching March Madness with me would likely ascertain. I grew up WITH RANDOLPH playing sports, which meant that someone won and some- On Jan. 20, Bridgewater and Randolph College in Lynchburg, Va., entered one lost. I love into an articulation agreement for students interested in pursuing a career in competition and coaching. BC graduates with a coaching minor who meet minimal admissions suppose that has requirements for the Randolph College Master of Arts in Coaching and Sport bled into my life Leadership (MACSL) program will be guaranteed one of three reserved slots in areas outside of annually. Bridgewater College’s sports. coaching minor is accredited This year, howev- by the National Committee for er, has led me to the Accreditation of Coach- Dr. Barbara Long reflect on the spirit ing Education (NCACE) and of cooperation. was the first undergraduate The pandemic has separated us in so many program at a private, four- ways, but, above all else, I have marveled year liberal arts college to be at the cooperation I found around me. At accredited. Aimed at preparing the beginning of the school year, I needed competent and quality coach- an adjunct faculty member, and immedi- es, the BC program is aligned ately four different local institutions tried to help me staff the position. -

Security & Privacy for Mobile Phones

Security & Privacy FOR Mobile Phones Carybé, Lucas Helfstein July 4, 2017 Instituto DE Matemática E Estatística - USP What IS security? • That GRANTS THE INFORMATION YOU PROVIDE THE ASSURANCES above; • That ENSURES THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL IN THIS SYSTEM KNOWS EACH other; • That TRIES TO KEEP THE ABOVE PROMISES forever. Security IS ... A System! • That ASSURES YOU THE INTEGRITY AND AUTHENTICITY OF AN INFORMATION AS WELL AS ITS authors; 1 • That ENSURES THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL IN THIS SYSTEM KNOWS EACH other; • That TRIES TO KEEP THE ABOVE PROMISES forever. Security IS ... A System! • That ASSURES YOU THE INTEGRITY AND AUTHENTICITY OF AN INFORMATION AS WELL AS ITS authors; • That GRANTS THE INFORMATION YOU PROVIDE THE ASSURANCES above; 1 • That TRIES TO KEEP THE ABOVE PROMISES forever. Security IS ... A System! • That ASSURES YOU THE INTEGRITY AND AUTHENTICITY OF AN INFORMATION AS WELL AS ITS authors; • That GRANTS THE INFORMATION YOU PROVIDE THE ASSURANCES above; • That ENSURES THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL IN THIS SYSTEM KNOWS EACH other; 1 Security IS ... A System! • That ASSURES YOU THE INTEGRITY AND AUTHENTICITY OF AN INFORMATION AS WELL AS ITS authors; • That GRANTS THE INFORMATION YOU PROVIDE THE ASSURANCES above; • That ENSURES THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL IN THIS SYSTEM KNOWS EACH other; • That TRIES TO KEEP THE ABOVE PROMISES forever. 1 Security IS ... A System! Eve | | | Alice "Hi" <---------------> "Hi" Bob 2 Security IS ... Cryptography! Eve | | | Alice "Hi" <----"*****"------> "Hi" Bob 3 Security IS ... Impossible! The ONLY TRULY SECURE SYSTEM IS ONE THAT IS POWERED off, CAST IN A BLOCK OF CONCRETE AND SEALED IN A lead-lined ROOM WITH ARMED GUARDS - AND EVEN THEN I HAVE MY doubts.