Dilemmas Facing Ngos in Coalition-Occupied Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hostage Through the Ages

Volume 87 Number 857 March 2005 A haunting figure: The hostage through the ages Irène Herrmann and Daniel Palmieri* Dr Irène Herrmann is Lecturer at the University of Geneva; she is a specialist in Swiss and in Russian history. Daniel Palmieri is Historical Research Officer at the International Committee of the Red Cross; his work deals with ICRC history and history of conflicts. Abstract: Despite the recurrence of hostage-taking through the ages, the subject of hostages themselves has thus far received little analysis. Classically, there are two distinct types of hostages: voluntary hostages, as was common practice during the Ancien Régime of pre-Revolution France, when high-ranking individuals handed themselves over to benevolent jailers as guarantors for the proper execution of treaties; and involuntary hostages, whose seizure is a typical procedure in all-out war where individuals are held indiscriminately and without consideration, like living pawns, to gain a decisive military upper hand. Today the status of “hostage” is a combination of both categories taken to extremes. Though chosen for pecuniary, symbolic or political reasons, hostages are generally mistreated. They are in fact both the reflection and the favoured instrument of a major moral dichotomy: that of the increasing globalization of European and American principles and the resultant opposition to it — an opposition that plays precisely on the western adherence to human and democratic values. In the eyes of his countrymen, the hostage thus becomes the very personification of the innocent victim, a troubling and haunting image. : : : : : : : In the annals of the victims of war, hostages occupy a special place. -

Kidnapping Is Booming Business

Colophon Published by IKV Pax Christi, July 2008 Also printed in Dutch and Spanish Address P.O. Box 19318 3501 DH UTRECHT The Netherlands www.ikvpaxchristi.nl [email protected] Circulation 300 copies Text IKV Pax Christi Marianne Moor Simone Remijnse With the cooperation of: Fundación País Libre, Ms. Olga Lucía Gómez Fundación País Libre, Ms. Claudia M. Llano Rodrigo Rojas Orozco Mauricio Silva Peer van Doormalen Paul Wolters Bart Weerdenburg Sarah Lachman Annemieke van Breukelen Carolien Groeneveld ISBN 978-90-70443-41-2 Design & Print Van der Weij BV Netherlands Contents Introduction 3 1 Growth on all fronts: kidnapping in a global context 5 1.1.. A study of kidnapping worldwidel 5 1.2. Kidnapping in the 21st century; risers and fallers 5 1.3. A tried and tested weapon in the struggle 7 1.4. A profitable sideline that delivers fast 7 1.5. The middle classes protest 8 1.6. The heavy hand used selectively 8 2. Kidnapping in the regions 11 2.1. Africa 11 2.1.1. Nigeria 12 2.2. Asia 12 2.3. The Middle East 15 2.3.1. Iraq 15 2.4. Latin America 16 2.4.1. A wave of kidnapping in the major cities 17 2.4.2. Central America: maras and criminal gangs 18 2.4.3. The Colombianization of Mexico and Trinidad &Tobago 18 2.4.4. Kidnapping and the Colombian conflict 20 3. The regionalization of a Colombian practice: 25 kidnapping in Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela 3.1. The kidnapping problem: 1995 – 2001 25 3.2. -

Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Updated May 16, 2005 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom accomplished a long-standing U.S. objective, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but replacing his regime with a stable, moderate, democratic political structure has been complicated by a persistent Sunni Arab-led insurgency. The Bush Administration asserts that establishing democracy in Iraq will catalyze the promotion of democracy throughout the Middle East. The desired outcome would also likely prevent Iraq from becoming a sanctuary for terrorists, a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission report. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is now showing substantial success, demonstrated by January 30, 2005 elections that chose a National Assembly, and progress in building Iraq’s various security forces. The Administration says it expects that the current transition roadmap — including votes on a permanent constitution by October 31, 2005 and for a permanent government by December 15, 2005 — are being implemented. Others believe the insurgency is widespread, as shown by its recent attacks, and that the Iraqi government could not stand on its own were U.S. and allied international forces to withdraw from Iraq. Some U.S. commanders and senior intelligence officials say that some Islamic militants have entered Iraq since Saddam Hussein fell, to fight what they see as a new “jihad” (Islamic war) against the United States. -

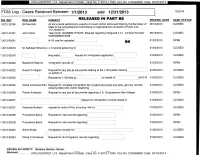

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

The Strange Kidnapping of Margaret Hassan

THE STRANGE KIDNAPPING OF MARGARET HASSAN By Matt Bojanovic December 27, 2004 Margaret Hassan was born Margaret Fitzsimmons in Dublin. While a student in London, she met an Iraqi student, Taheen Ali Hassan. They say she was 17, and he was 26. They fell in love, married, and went to live in Iraq in 1972. She took Iraqi citizenship, converted to Islam and learned Arabic, which they say she spoke perfectly, with an Iraqi accent, as if she had been born there. After the Gulf War of 1991, she became director of Care International in Baghdad. She organized the building of hospitals and undertook the restoration of Iraq's drinking water system, which had been attacked by NATO bombers. It was an impossible task, because of the Western embargo on spare parts and supplies. Justin Huggler writes in The Independent of November 17: 'When they heard that she had been kidnapped, they came on to the streets of Baghdad in their wheelchairs to demand her release. Children from a school for the deaf came out holding placards demanding the release of "Mama Margaret." "If it wasn't for her, we would probably have died," Ahmed Jubair, a small boy in a wheelchair, said that day. "She built us a hospital and took care of us. She made us feel happy again." There can be few greater epitaphs.' Charity was not enough to Margaret Hassan; it was not enough to help a few thousands-- or even a few millions--of poor unfortunates. She knew whose cluster bombs were putting children in wheelchairs. -

GOP Parties in OC

News Sports Three-strikes law not Bowling for Fullerton: amended, state to proceed Titans striking up with stem cell research 3 success on the lanes 6 California State University, Fullerto n Daily Titan We d n e s d a y, N o v e m b e r 3 , 2 0 0 4 www.dailytitan.com Volume 79, Issue 3 6 BUSH WINS? Bush holds the lead but Kerry campaign does not concede; dispute over Ohioʼs results draws similarities to the 2000 presidential election By RUDY GHARIB and RYAN TOWNSEND Daily Titan Elections Coordinator and Asst. News Editor As of early Wednesday morning, Bob Mulholland, California the American people were with- Democratic Party spokesman, was out an official winner of the 2004 confident on Tuesday afternoon. Presidential Election. “You can bank on this, talking While Bush led statistically, heads on the east coast will have Kerry refused to concede defeat to wait for Californiaʼs exit polls as both parties waited on the final to declare John Kerry the winner,” results in Ohio. he said. During the tumultuous closing Near midnight Tuesday, that opti- weeks of the campaign, much of the mism had faded but party leaders buzz focused on young voters and held fast. the possibility that they might swing Mary Gutierrez, communications the contest. director for California Democratic Despite efforts from celebrities Party, said, “We havenʼt given up and music television stations, the thatʼs for sure.” vaunted youth vote failed to mate- “Democrats tend to vote absentee rialize. and we tend to use most of the pro- Nationwide, the 18-29 turnout visional ballots,” she said. -

THE PRESIDENT: Thank You All

PRESIDENT BUSH DISCUSSES THE WAR ON TERROR National Endowment for Democracy, Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, Washington DC 6 October 2005 Transcript from www.whitehouse.gov THE PRESIDENT: Thank you all. (Applause.) Thank you all. Please be seated. (Applause.) Thank you for the warm welcome. I'm honored once again to be with the supporters of the National Endowment for Democracy. Since the day President Ronald Reagan set out the vision for this Endowment, the world has seen the swiftest advance of democratic institutions in history. And Americans are proud to have played our role in this great story. Our nation stood guard on tense borders; we spoke for the rights of dissidents and the hopes of exile; we aided the rise of new democracies on the ruins of tyranny. And all the cost and sacrifice of that struggle has been worth it, because, from Latin America to Europe to Asia, we've gained the peace that freedom brings. In this new century, freedom is once again assaulted by enemies determined to roll back generations of democratic progress. Once again, we're responding to a global campaign of fear with a global campaign of freedom. And once again, we will see freedom's victory. (Applause.) Vin, I want to thank you for inviting me back. And thank you for the short introduction. (Laughter.) I appreciate Carl Gershman. I want to welcome former Congressman Dick Gephardt, who is a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy. It's good to see you, Dick. And I appreciate Chris Cox, who is the Chairman of the U.S. -

The Christian Science Monitor and the Kidnapping of Jill Carroll CSJ-08

CSJ‐ 08 ‐ 0012.0 A Life on the Line: The Christian Science Monitor and the kidnapping of Jill Carroll On Saturday, January 7, 2006, Christian Science Monitor Managing Editor Marshall Ingwerson was woken by a 4:30 a.m. phone call—and it was not good news. A Monitor stringer in Baghdad, Jill Carroll, had been kidnapped. No one knew who had taken her, nor whether the kidnappers were motivated by money or ideology. Kidnappings had become only too common in Iraq; journalists in particular were favorite targets. The Monitor itself had even experienced another freelancer kidnapped and killed. Ingwerson knew the paper would have to make decisions quickly. Trying to manage a kidnapping in any context was a challenge, and involved a staggering array of players. That Carroll was in Iraq only multiplied the numbers. There were the many editors at the Monitor, Carrollʹs family members, news media, US government agencies, and nongovernmental organizations. There were also the bureau in Baghdad, the US military authorities in Iraq, Iraqi government officials and purported go‐betweens to terrorist organizations. Monitor editors had to decide not only whom to work with, but when to call on which group or individual. As a start, Ingwerson and a few key editors each took specific responsibilities. One represented the Monitor in public; another worked with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and its counterparts abroad; another dealt with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); and still another stayed in constant communication with Carrollʹs family members. The reporters in the Baghdad bureau were also eager to assist in any way possible. -

Terrorism and the Internet: New Media—New Threat?

Parliamentary Affairs Vol. 59 No. 2, 2006, 283–298 Advance Access Publication 10 February 2006 Terrorism and the Internet: New Media—New Threat? BY MAURA CONWAY Downloaded from ‘Terrorists use the Internet just like everybody else’ –Richard Clarke – former White House cyber security chief1 THIS article is centrally concerned with what Resnick describes as ‘Political uses of the Net’, the employment of the Internet by ordinary citizens, political activists, organised interests, governments and others http://pa.oxfordjournals.org/ to achieve political goals which has little or nothing to do with the Internet per se.2 Specifically, the focus here is on the use(s) made of the Internet by terrorist groups based primarily (though not exclusively) on the United Kingdom’s experience. What are terrorist groups attempting to do by gaining a foothold in cyberspace? A small number of research- ers have addressed this question in the past 5 years.3 Probably the best known of these analyses is Gabriel Weimann’s report for the US Insti- at York University Libraries on March 2, 2015 tute of Peace entitled www.terrorism.net: How Modern Terrorism Uses the Internet (2004). Weimann identifies eight major ways in which, he says, terrorists currently use the Internet. These are psychological war- fare, publicity and propaganda, data mining, fund raising, recruitment and mobilization, networking, information sharing and planning and coordination.4 Having considered Weimann’s categorisation in con- junction with those suggested by Cohen, Furnell and Warren and Thomas,5 the analysis below relies upon what have been determined to be the five core terrorist uses of the Net: information provision, finan- cing, networking, recruitment and information gathering. -

A Timeline of Events Relating to Iraq 1970-2011

A Timeline of Events Relating to Iraq 1970-2011 1970-72 Iraq’s oil industry nationalized. 1979 Iran’s new Islamic government led by Ayatollah Khomeini sought to expand its religious and political influence across the Middle East, leading to tensions between Iraq and Iran, and between the Iraqi government and the Shi’a population. 1980 –1988 More than one million Iranians and Iraqis died during the Iran-Iraq. The US government secretly assisted both Iraqis and Iranians, including arms shipped as part of the Iran-Contra Affair. During "the war of the cities" civilians living in the major cities of both countries were deliberately targeted. Several thousand Iraqis including more than 4,000 Kurds in Halabja were killed by their own government, allegedly for assisting Iran. By war’s end, Iraq’s debt was $50 billion. 1990 Encouraged by Ambassador April Glaspie’s comment that the US had “no opinion on Arab- Arab conflicts,” Iraq invaded Kuwait over oil and debt issues. The UN Security Council quickly imposed economic sanctions until Iraqi troops withdrew from Kuwait. (Resolution 661) Arab efforts to resolve the situation were consistently undermined by the Bush Administration. 1991 Despite heavy opposition from their constituents, the Senate voted to go to war, influenced by testimony that Iraqi soldiers took Kuwaiti babies out of incubators; it later emerged that this testimony was invented by Hill and Knowlton on behalf of their client, Citizens for a Free Kuwait. Using bribes and threats, the US forged a “coalition of the willing” to oust Iraqi troops from Kuwait. US peace activists act as “human shields” hoping to affect US military operations. -

Is the Kidnapping of CARE's Margaret Hassan a CIA-Mossad

Is the Kidnapping of CARE’s Margaret Hassan a CIA- Mossad Op? By Kurt Nimmo Theme: Terrorism, US NATO War Agenda Global Research, October 28, 2004 In-depth Report: IRAQ REPORT http://www.kurtnimmo.com/blog/ 29 June 2005 It makes absolutely no sense. Margaret Hassan, director of the humanitarian group CARE International, who has joint British-Iraqi citizenship, was kidnapped yesterday morning in Iraq. Although nobody has claimed responsibility for abducting Ms. Hassan, the immediate assumption is she was grabbed by the Iraqi resistance or al-Zarqawi, the latter accused of all manner of barbarity, including beheading kidnap victims. But why would the resistance kidnap somebody who has provided humanitarian assistance to the people of Iraq for 25 years? Is it possible the Iraqi resistance wants to deny the Iraqi people humanitarian assistance? Of course not. In America, the corporate media answers the above question every day—the Iraqi resistance is fanatical, murderous, nothing more than a loose confederation of terrorists, criminals, Islamic madmen, demented sadists who blow up car bombs in crowded market squares and kill women and children, their own neighbors. However, there is another possible explanation: the kidnapping of Margaret Hassan is part of a counterinsurgency operation devised to make the resistance look bad and thus turn world opinion against it. Before you tell me to don my tinfoil hat, consider the following: as crack investigative journalist Seymour Hersh reported in June, Mossad is busily at work in Iraq, primarily in the Kurdish areas of the country. A senior CIA official confirmed this, according to Hersh. -

Iraq's Hostage Crisis: Kidnappings, Mass Media and the Iraqi Insurgency

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Faculty and Researcher Publications Faculty and Researcher Publications 2004-12-01 Iraq's Hostage Crisis: Kidnappings, Mass Media and the Iraqi Insurgency al-Marashi, Ibrahim http://hdl.handle.net/10945/37387 ttp://www.gloria-center.org/2004/12/al-marasi-2004-12-01/ !raq’s Hostage Crisis: Kidnappings, Mass Media and the !raqi !nsurgency December 1, 2004 gloria-center.org !his article analyzes the use of kidnapping as a tactic by the Iraqi insurgency in its effort to influence Iraqi, Arab, and Muslim public opinion and politics, as well as the international arena. It assesses how this method has yielded important advantages for the insurgents, despite the horror and opposition this behavior arouses in the outside world. Since te ousting of Saddam Hussein?¯?¿?½s regime in 2003, tere ave been ample reports covering and analyzing te Iraqi insurgency?¯?¿?½s diverse use of armed tactics suc as roadside explosives, mortar attacks, and suicide bombings. At te same time, toug, tere as been less attention paid and understanding developed on te insurgents?¯?¿?½ media campaign directed at Iraqis as well as te Arab and Muslim worlds more generally. Observers of te Iraqi insurgency agree tat its combat tecniques ave grown more sopisticated since President George W. Bus announced te end of major combat operations in May 2003. A media strategy, owever, as simultaneously complemented tese military activities. Iraqi insurgents[1] employed tese metods in order to garner sympaty from te Iraqi population for teir ?¯?¿?½struggle,?¯?¿?½ wile keeping te international media spotligt on te American-led occupation of Iraq.