An Interim Report EXCAVATIONS AT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grapevine Summer 2017 Serving the Community

The Grapevine Summer 2017 serving the community Thu & Fri For more details - please Juniors Youth Club contact Stve McC at Ely & Caerau Festival 2017 - please contact Stve McC [email protected]. at smccambridge@cardiff. uk. gov.uk. Cambrensis Choir Fri 30th June Bethel Church, Flower Festival Preview Michaelston Rd Church of the Resurrection 8pm. 7pm. Thu & Fri Summer Carnival Juniors Youth Club Ely & Caerau Childrens - please contact Stve McC at Centre, smccambridge@cardiff .gov. Michaelston Rd uk. 10am to 3pm. Fri 7th July Sat 1st July Pencaerau Schools Flower Festival Open 5-A-Side Football Resurrection Church Fete 11am to 1pm. Sat 8th July Festival Big Day It’s that time of the year. Mon 3rd July 12pm to 5pm, Western Eys Down novelty Bingo Leisure Centre. Make sure you are at our local festival. Recreation Play Centre 6:30pm to 9pm. Sun 9th July Thu 22nd June Mon 26th June Strawberry Tea in the Elympics, Wilson Road Eyes Down Novelty Bingo Juniors Youth Club grounds of the Church of the Recreation Grounds Recreation Play Centre - please contact Stve McC Resurrection. 1pm to 3pm. 6:30pm to 9pm. at smccambridge@cardiff. Welcome to stay for gov.uk. Churches Together Songs Sat 24th June Juniors Youth Club of Praise at 5:30pm. Nant Caerau Summer Fair - please contact Stve McC Tue 4th July 11am to 2pm. at smccambridge@cardiff. Re-opening of North Ely gov.uk. Youth Centre We are now looking forward to developing new projects to investigate even further into the history and heritage of Ely and Caerau, with particular focus on our very own Iron Age hillfort. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

and Annual Report ended 31 July 2018 Year Financial StatementsFinancial Cardiff University Annual Report and Financial Statements | Year ended 31 July 2018 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. They address the global challenges we face, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate, environ- mental degradation, prosperity, and peace and justice. As a signatory to the Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges Accord, the University has committed to aligning and mapping its activities to the relevant goals. In this report you will see within each section icons against the relevant goal. For more information on the SDGs, please visit: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ sustainable-development-goals/ Contents Annual Strategic Review 3 Members of Council Financial Review 19 Chair: Professor Stuart Palmer Corporate Governance Statement 24 Vice Chair: Public Benefit Statement 27 Rev Canon Gareth Powell Vice-Chancellor: Responsibilities of the Council of Cardiff University 28 Professor C Riordan Independent Auditors’ Report 29 Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Professor K Holford Consolidated and University Statements of Comprehensive Income 33 Mr R Aggarwal [to 31 July 2018] Statements of Changes in Reserves 34 Ms F Al-Dhahouri Professor R Allemann Balance Sheets 35 [from 1 August 2018] Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 36 Mr P Baston Dr C Bell Notes to the Financial Statements 37 Professor G Boyne [to 31 July 2018] Ms H Cooke [to 30 -

(Public Pack)Agenda Dogfen I/Ar Gyfer Cydbwyllgor Archifau

AGENDA Committee GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE Date and Time FRIDAY, 21 MAY 2021, 2.00 PM of Meeting Venue REMOTE MEETING Membership Councillor John (Chairperson) Councillors Colbran, Burnett, Cowan, Cunnah, George, Henshaw, Higgs, Jarvie, B Jones, K Jones, R Lewis, W Lewis, Robson and Smith Time approx. 1 Apologies for Absence To receive apologies for absence. 2 Declarations of Interest To be made at the start of the agenda item in question, in accordance with the Members’ Code of Conduct. 3 Minutes (Pages 5 - 6) To approve as a correct record the minutes of the previous meeting. 4 Report for the period 1 March - 30th April 2021 (Pages 7 - 22) 5 Strategic Plan 2021-2026 (Pages 23 - 36) 6 National Broadcast Archive (Pages 37 - 40) 7 Glamorgan Archives Outturn Report 2020/21 (Pages 41 - 64) This document is available in Welsh / Mae’r ddogfen hon ar gael yn Gymraeg 8 Dates of next meetings To consider the proposed dates of meetings for 2021/22: 20th August 2021 19th November 2021 18th February 2022 20th May 2022 Davina Fiore Director Governance & Legal Services Date: Monday, 17 May 2021 Contact: Andrea Redmond, 02920 872434, [email protected] This document is available in Welsh / Mae’r ddogfen hon ar gael yn Gymraeg WEBCASTING This meeting will be filmed for live and/or subsequent broadcast on the Council’s website. The whole of the meeting will be filmed, except where there are confidential or exempt items, and the footage will be on the website for 6 months. A copy of it will also be retained in accordance with the Council’s data retention policy. -

The City and County of Cardiff, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY AND COUNTY OF CARDIFF, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE REPORT FOR THE PERIOD REPORT OF: 1st March – 30th April 2021 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1st March to 30th April 2021 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 3. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff Maintain establishment Lowis Lovell, Archivist, returned from maternity leave in early-April. Continue skill sharing and volunteer programme 20 volunteers continue to work remotely on projects, contributing approximately 325 hours during the quarter. This is significantly lower than the last quarter. Despite additional digitisation being undertaken during December, in anticipation of a tightening in Covid19 restrictions, it was not enough to satisfy the demand for resources by volunteers during a winter lockdown. One volunteer described volunteering as a ‘life line’ during this difficult period. Now that staff have returned to the office work is underway to digitise the next stage of their projects and provide new material to volunteers who have finished their allocation of images. A project launched last quarter to produce a finding aid for the 1877 diary of Tudor Crawshay has been completed. The work will checked by staff and then attached to the catalogue entry for the diary. -

Postgraduate

Cardiff University Postgraduate Prospectus 2017 www.cardiff.ac.uk/postgraduate 95% of postgraduates Top5 employed or in further study UK university 6 months after graduation for research Source: HESA Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education 2013/14 survey QUALITY Source: Research Excellence Framework 2014, see page 12 Important Legal Information The contents of this prospectus Where there is a difference between example, when we might make relate to the Entry 2017 admissions the contents of this prospectus changes to your chosen course or to cycle and are correct at the time and our website, the contents of student regulations. It is, therefore, of going to press in June 2016. the website take precedence and important you read them and However, there is a lengthy period represent the basis on which we understand them. If you are not able of time between printing this intend to deliver our services to you. to access information online please prospectus and applications being Any offer of a place to study at contact us: made to and processed by us, so Cardiff University is subject to Email: postgradenquiries please check our website before terms and conditions, which can @cardiff.ac.uk making an application in case there be found on our website www. Tel: +44 (0)29 2087 4455 are any changes to the course you cardiff.ac.uk/offerterms and Your degree: Students admitted to are interested in or to other facilities which you are advised to read Cardiff University study for a Cardiff and services described here. before making an application. The University degree. -

Time Team Caerau Report

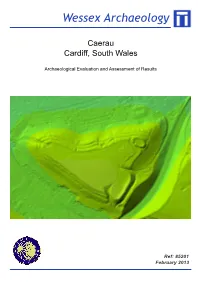

Wessex Archaeology Caerau Cardiff, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 85201 February 2013 Caerau Cardiff, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared for: Videotext Communications Ltd 11 St Andrews Crescent CARDIFF CF10 3DB Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB www.wessexarch.co.uk February 2013 Report Ref: 85201.01 © Wessex Archaeology Ltd 2013, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Ltd is a Registered Charity No. 287786 (England & Wales) and SC042630 (Scotland) Caerau, Cardiff, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation Report and Assessment of Results Quality Assurance Project Code 85201 Accession N/A Client N/A Code Ref. Planning N/A Ordnance Survey 313335, 174970 Application (OS) national grid Ref. reference (NGR) Version Status* Prepared by Checked and Approver’s Signature Date Approved By v01 F N Brennan L Mepham 12/02/13 File: File: File: File: File: * I = Internal Draft; E = External Draft; F = Final DISCLAIMER THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT WAS DESIGNED AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF A REPORT TO AN INDIVIDUAL CLIENT AND WAS PREPARED SOLELY FOR THE BENEFIT OF THAT CLIENT. THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT DOES NOT NECESSARILY STAND ON ITS OWN AND IS NOT INTENDED TO NOR SHOULD IT BE RELIED UPON BY ANY THIRD PARTY. TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW WESSEX ARCHAEOLOGY WILL NOT BE LIABLE BY REASON OF BREACH OF CONTRACT NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE (WHETHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL) OCCASIONED TO ANY PERSON ACTING OR OMITTING TO ACT OR REFRAINING FROM ACTING IN RELIANCE UPON THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT ARISING FROM OR CONNECTED WITH ANY ERROR OR OMISSION IN THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE REPORT. -

Cwrt-Yr-Ala Road, Ely, Cardiff

Archaeology Wales Cwrt-yr-Ala Road, Ely, Cardiff Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment By Philip Poucher Report No. 1214 Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 E-mail: [email protected] Archaeology Wales Cwrt-yr-Ala Road, Ely, Cardiff Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Prepared For: Barrett Homes SW Edited by: Mark Houliston Authorised by: Mark Houliston Signed: Signed: Position: MD Position: MD Date: 4/4/2014 Date: 7/4/2014 By Philip Poucher Report No. 1214 March 2014 Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Non-Technical Summary 1 1.Introduction 2 2.Site Description 2 3. Methodology 3 4. Archaeological and Historical Background 4 4.1 Previous Archaeological Studies 4 4.2 The Historic Landscape 5 4.3 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 5 4.4 Listed Buildings 5 4.5 Known Archaeological Remains and Historical Development 6 5.Map Regression 10 6. Aerial Photographs 14 7.Site Visit 14 8.Views 15 9.Impact Assessment 16 9.1 Previous impacts 16 9.2 Potential impacts from proposed development 16 9.3 Assessment of archaeological potential and importance 17 9.4 Mitigation 17 10.Conclusion 18 11.Sources 19 Appendix I: Gazetteer of SAMs & Listed Buildings Appendix II: Gazetteer of sites recorded on the regional HER Appendix III: List of sites recorded on the NMR Appendix IV: Specification List of Figures Figure 1 Site location Figure 2 Site boundary plan Figure 3 Proposed development plan Figure 4 Designated landscapes and sites Figure 5 Sites recorded on the regional HER and NMR Figure 6 Extract from an estate map of 1774 Figure 7 Extract from the 1841 Caerau parish tithe map Figure 8 Extract from the 1880 Ordnance Survey map Figure 9 Extract from the 1919-20 Ordnance Survey map i List of Photos Photo 1 View NW across site area Photo 2 View W across site area Photo 3 View N of site area from Cwrt-yr-Ala Road Photo 4 View N of site area from Cwrt-yr-Ala Road Photo 5 View north across the glasshouses. -

An Interim Report EXCAVATIONS at CAERAU

CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 An Interim Report By O. Davis & N. Sharples CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 Interim Report by O. Davis & N. Sharples with contributions by M. Allen, P. Hodkinson & R. Madgewick CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 National Primary Reference Number (NPRN) 94517 Cadw Scheduled Ancient Monument No. GM018 Cardiff Studies in Archaeology Specialist Report 35 © The authors 2015 Oliver Davis and Niall Sharples, ISBN 978-0-9568398-4-8 Published by the Department of Archaeology & Conservation School of History Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University, John Percival Building, Colum Drive, Cardiff, CF10 3EU Tel: +44 (0)29 208 74470 Fax: +44 (0)29 208 74929 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission of the authors. Designed by Cardiff Archaeological Illustration and Design Software: Adobe Creative Suite 6 Design Premium Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 3 3. Previous Archaeological Work 7 4. Project Aims & Objectives 9 5. Excavation Methodology 13 6. Excavation Results 15 7. Finds 53 8. Palaeo - Environmental Summary 59 9. Summary 73 10. Community Impact 75 11. Bibliography 97 Appendix 1- Context Lists 91 Appendix 2 - Small Find List 97 Appendix 3 - Sample List 99 1. Introduction Four weeks of excavation at Caerau Hillfort (NPRN permission to carry out the investigations. The wooded 94517; SAM GM018) were carried out from 30 June to 25 boundary earthworks of the hillfort are owned by Cardiff July 2014 and involved the excavation of four trenches. -

Connected Communities Festival Programme 2014

FESTIVAL PROGRAMME CONNECTED COMMUNITIES FESTIVAL CARDIFF 2014 CONTENTS 2 | The Connected Communities Festival 3 | Programme at a glance 10 | St. David’s Conference Centre timetable 11 | Motorpoint Arena timetable 12 | OffSite and Evening timetable 14 | Venues 15 | Speakers 16 | St. David’s Conference Centre breakout sessions 21 | Motorpoint Arena breakout sessions 26 | OffSite & evening breakout sessions 30 | St. David’s Conference Centre exhibition stands 36 | Motorpoint Arena exhibition stands 41 | Festival bus services & social media 1 CONNECTED COMMUNITIES FESTIVAL PROGRAMME THE CONNECTED COMMUNITIES FESTIVAL elcome to the first Connected Communities Festival. The activities Woutlined in this publication are a sign of the extraordinary range and diversity of this important and groundbreaking research programme. They are also a sign of its commitment to outreach and engagement and to ensuring that communities themselves are closely involved in the research undertaken, not as objects of research, but as partners and collaborators. We’re delighted that the Festival is taking place in Wales and that a key focus of the next few days will be Welsh community life, the rich and vital work of community groups in Wales and their many exciting collaborations with academic researchers. With around 300 projects being funded through the programme and over 400 project partners and community organisations, the Festival can only showcase a selection of the range of research being undertaken. But, as you will see and we hope you will experience, the programme is a full and exciting one, involving performances, workshops, films, bazaars, demonstrations, guided walks, and much more. We hope you enjoy what the next few days have to offer. -

An Interim Report EXCAVATIONS at CAERAU HILLFORT

CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 An Interim Report By O. Davis & N. Sharples CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 Interim Report by O. Davis & N. Sharples with contributions by M. Allen, P. Hodkinson & R. Madgewick CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 35 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2014 National Primary Reference Number (NPRN) 94517 Cadw Scheduled Ancient Monument No. GM018 Cardiff Studies in Archaeology Specialist Report 35 © The authors 2015 Oliver Davis and Niall Sharples, ISBN 978-0-9568398-4-8 Published by the Department of Archaeology & Conservation School of History Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University, John Percival Building, Colum Drive, Cardiff, CF10 3EU Tel: +44 (0)29 208 74470 Fax: +44 (0)29 208 74929 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission of the authors. Designed by Cardiff Archaeological Illustration and Design Software: Adobe Creative Suite 6 Design Premium Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 3 3. Previous Archaeological Work 7 4. Project Aims & Objectives 9 5. Excavation Methodology 13 6. Excavation Results 15 7. Finds 53 8. Palaeo - Environmental Summary 59 9. Summary 73 10. Community Impact 75 11. Bibliography 97 Appendix 1- Context Lists 91 Appendix 2 - Small Find List 97 Appendix 3 - Sample List 99 1. Introduction Four weeks of excavation at Caerau Hillfort (NPRN permission to carry out the investigations. The wooded 94517; SAM GM018) were carried out from 30 June to 25 boundary earthworks of the hillfort are owned by Cardiff July 2014 and involved the excavation of four trenches. -

The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust HALF-YEARLY REVIEW

The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust HALF-YEARLY REVIEW 2016-17 AND ANNUAL REVIEW OF PROJECTS 2015-2016 The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Ltd Heathfield House Heathfield Swansea SA1 6EL Front cover photographs: left to right, GGAT 141:Hen Dre’r Mynydd, Blaen Rhondda: Community Geophysical and Historical Survey. GGAT 137: The Call to Arms-Southeast Wales and the First World War. GGAT 138: Husbandry in Glamorgan and Gwent: Penrice Fishpond, Coed-y-Felin; Circular segmental fishpond, view to southwest. Contents REVIEW OF CADW PROJECTS APRIL 2015 — MARCH 2016 .......................................... 4 GGAT 1 Regional Heritage Management Services ............................................................ 4 GGAT 43 Regional Archaeological Planning Management and GGAT 92 Local Development Plan Support ................................................................................................. 7 GGAT 100 Regional Outreach ........................................................................................... 9 GGAT 118 Accessing Archaeological Planning Management Derived Data ................... 13 GGAT 135 Historic Environment Record Management and Enhancement ..................... 15 GGAT 136 Historic Environment Record Enhancement – Military Sites.......................... 18 GGAT 137 Southeast Wales and the First World War ..................................................... 19 GGAT 138 Southeast Wales Medieval and Early Post-medieval Husbandry in Glamorgan-Gwent (c1100-1750) ..................................................................................... -

An Interim Report EXCAVATIONS at CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF

CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY 36 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2015 An Interim Report By O. Davis & N. Sharples With contributions by Dave Wyatt & Peter Bye-Jensen CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 36 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2015 Interim Report by O. Davis & N. Sharples with contributions by D. Wyatt & P. Bye-Jensen EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2015 National Primary Reference Number (NPRN) 94517 Cadw Scheduled Ancient Monument No. GM018 Cardiff Studies in Archaeology Specialist Report 36 © The authors 2016 Oliver Davis and Niall Sharples, ISBN 978-0-9568398-4-8 Published by the Department of Archaeology & Conservation School of History Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University, Humanities Building, Colum Drive, Cardiff, CF10 3EU Tel: +44 (0)29 208 74470 Fax: +44 (0)29 208 74929 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission of the authors. Designed by Cardiff Archaeological Illustration and Design Software: Adobe Creative Cloud Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Project Aims & Objectives 3 3. Excavation Methodology 5 4. Excavation Results 7 5. Finds 43 6. Summary 47 7. Community Impact 51 8. Bibliography 61 Appendix 1- Context Lists 65 Appendix 2 - Small Find List 81 Appendix 3 - Sample Lists 93 1. Introduction Four weeks of excavation at Caerau Hillfort (NPRN significant research with a broad mission to engage with 94517; SAM GM018) (Figure 1.1) were carried out from the public, particularly the local communities of Caerau 22 June to 17 July opening five trenches.