Digging Caerau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grapevine Summer 2017 Serving the Community

The Grapevine Summer 2017 serving the community Thu & Fri For more details - please Juniors Youth Club contact Stve McC at Ely & Caerau Festival 2017 - please contact Stve McC [email protected]. at smccambridge@cardiff. uk. gov.uk. Cambrensis Choir Fri 30th June Bethel Church, Flower Festival Preview Michaelston Rd Church of the Resurrection 8pm. 7pm. Thu & Fri Summer Carnival Juniors Youth Club Ely & Caerau Childrens - please contact Stve McC at Centre, smccambridge@cardiff .gov. Michaelston Rd uk. 10am to 3pm. Fri 7th July Sat 1st July Pencaerau Schools Flower Festival Open 5-A-Side Football Resurrection Church Fete 11am to 1pm. Sat 8th July Festival Big Day It’s that time of the year. Mon 3rd July 12pm to 5pm, Western Eys Down novelty Bingo Leisure Centre. Make sure you are at our local festival. Recreation Play Centre 6:30pm to 9pm. Sun 9th July Thu 22nd June Mon 26th June Strawberry Tea in the Elympics, Wilson Road Eyes Down Novelty Bingo Juniors Youth Club grounds of the Church of the Recreation Grounds Recreation Play Centre - please contact Stve McC Resurrection. 1pm to 3pm. 6:30pm to 9pm. at smccambridge@cardiff. Welcome to stay for gov.uk. Churches Together Songs Sat 24th June Juniors Youth Club of Praise at 5:30pm. Nant Caerau Summer Fair - please contact Stve McC Tue 4th July 11am to 2pm. at smccambridge@cardiff. Re-opening of North Ely gov.uk. Youth Centre We are now looking forward to developing new projects to investigate even further into the history and heritage of Ely and Caerau, with particular focus on our very own Iron Age hillfort. -

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd ANGOR UNIVERSITY Excavations, July and August 2013 Karl, Raimund; Waddington, Kate Published: 01/01/2015 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Karl, R., & Waddington, K. (2015). Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations, July and August 2013: Interim report. (Bangor Studies in Archaeology; Vol. 12). Bangor University. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations July and August 2013 Interim Report Kate Waddington and Raimund Karl Bangor: Gwynedd, January 2016 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 12 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 1 2 Also available in this series: Report No. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019

Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019. William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Lidar Image of Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire (© 2019 Chilterns Conservation Board) William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, 2019. Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019. William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Introduction In 2017 the Chilterns Conservation Board was awarded a £695,600 grant by the Heritage Lottery Fund towards a four year £895,866 project to discover and conserve the hillforts of the Chilterns. The project is entitled “Beacons of the Past: Hillforts in the Chiltern Landscapes” and it aims to engage and inspire a large, diverse range of people to discover, conserve and enjoy the Chilterns' Iron Age hillforts and their prehistoric chalk landscapes. The nineteen Iron Age hillforts form one of the densest concentrations of hillforts in the country. The project is managed by Dr Wendy Morrison, supported by Dr Edward Peveler. A central component of the project is a detailed Lidar survey which will cover about 1400 km2. of the Chiltern Hills to provide new archaeological information, particularly for those areas covered by woodland. Important also is geophysical survey to investigate areas within and adjacent to a selected number of hillforts. Desborough Castle, situated within a large housing estate at High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, is one of the hillforts (or possible hillforts) selected for geophysical survey. A magnetometer (gradiometer) survey was conducted over areas of open grassland at and adjacent to Desborough Castle in early July with the aim of detecting archaeological features which might confirm an Iron Age date of certain earthworks and identifying potential locations for future limited trial excavation. -

The Earth and Timber Castles of the Llŷn Peninsula in Their

The Earth and Timber Castles of the Llŷn Peninsula in their Archaeological, Historical and Landscape Context Dissertation submitted for the award of Bachelor of Arts in Archaeology University of Durham, Department of Archaeology James Gareth Davies 2013 1 Contents List of figures 3-5 Acknowledgements 6 Survey Location 7 Abstract 8 Aims and Objectives 9 Chapter 1: Literature review 10-24 1.1: Earth and Timber castles: The Archaeological Context 10-14 1.2: Wales: The Historical Context 15-20 1.3: Study of Earth and Timber castles in Wales 20-23 1.4: Conclusions 23-24 Chapter 2: Y Mount, Llannor 25-46 2.1:Topographic data analysis 25-28 2.2: Topographical observations 29-30 2.3: Landscape context 30-31 2.4: Geophysical Survey 2.41: Methodology 32-33 2.42: Data presentation 33-37 2.43: Data interpretation 38-41 2.5: Documentary 41-43 2.6: Erosion threat 44-45 2.7: Conclusions: 45 2 Chapter 3: Llŷn Peninsula 46-71 3.1: Context 46-47 3.2: Survey 47 3.3: Nefyn 48-52 3.4: Abersoch 53-58 3.5: New sites 59 3.6: Castell Cilan 60-63 3.7: Tyddyn Castell 64-71 Chapter 4: Discussion 72-81 4.1 -Discussion of Earth and Timber castle interpretations in Wales 72-77 4.2- Site interpretation 78 4.3- Earth and Timber castle studies- The Future 79-80 Figure references 81-85 Bibliography 86-91 Appendix 1: Kingdom of Gwynedd Historical Chronology (mid 11th to mid 12th centuries) 92-94 Appendix 2: Excavated sites in Wales 95-96 Appendix 3: Ty Newydd, Llannor- Additional Resources 97-99 Appendix 4: Current North Wales site origin interpretations 100 3 List of figures 1. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

and Annual Report ended 31 July 2018 Year Financial StatementsFinancial Cardiff University Annual Report and Financial Statements | Year ended 31 July 2018 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. They address the global challenges we face, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate, environ- mental degradation, prosperity, and peace and justice. As a signatory to the Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges Accord, the University has committed to aligning and mapping its activities to the relevant goals. In this report you will see within each section icons against the relevant goal. For more information on the SDGs, please visit: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ sustainable-development-goals/ Contents Annual Strategic Review 3 Members of Council Financial Review 19 Chair: Professor Stuart Palmer Corporate Governance Statement 24 Vice Chair: Public Benefit Statement 27 Rev Canon Gareth Powell Vice-Chancellor: Responsibilities of the Council of Cardiff University 28 Professor C Riordan Independent Auditors’ Report 29 Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Professor K Holford Consolidated and University Statements of Comprehensive Income 33 Mr R Aggarwal [to 31 July 2018] Statements of Changes in Reserves 34 Ms F Al-Dhahouri Professor R Allemann Balance Sheets 35 [from 1 August 2018] Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 36 Mr P Baston Dr C Bell Notes to the Financial Statements 37 Professor G Boyne [to 31 July 2018] Ms H Cooke [to 30 -

The Anarchy: War and Status in 12Th-Century Landscapes of Conflict

Book review article: ‘The Anarchy: War and Status in 12th century Landscapes of Conflict’ Chapter 2, Historical Outline and the Geog- raphy of ‘Anarchy’, is a good summary of complex events, including the important point that control of Normandy was central to the struggle (p 30). The geographical spread of activity is illustrated by interesting maps of itineraries, particularly of Stephen, divided into phases of his reign. Early on, he went to Cornwall and north onto Scottish territory (in both cases accompanied by his army) but most- ly he was in central and southern England, with forays to Lincolnshire and, occasionally, York. WAGING WAR: FIELDS OF CONFLICT AND SIEGE WARFARE The subject of Chapter 3 (title above) is a critical issue in assessments of the Anarchy. Creighton and Wright note that pitched battles were rare and sieges dominated (p 34, 40). Church authorities attempted to regulate war, in particular protecting the Church’s posses- sions (p 36), but also deployed ‘spiritual weap- ons’, such as the saints’ banners on the mast The Anarchy: War and Status in (the Standard) at Northallerton (p 45). And a 12th-Century Landscapes of Conflict bishop, in a pre-battle speech at Northallerton, Authors: Oliver H. Creighton as recorded by Henry of Huntingdon, promised Duncan W. Wright that English defenders killed in combat would Publishers: Liverpool University Press, Ex- be absolved from all penalty for sin. [HH 71] eter Studies in Medieval Europe Laying waste enemies’ estates was a normal ISBN 978-1-78138-242-4 by-product of Anglo-Norman warfare, not Hardback, 346 pages unique to Stephanic conflict (p 37-8). -

Living in an Early Tudor Castle: Households, Display, and Space, 1485-1547 Audrey Maria Thorstad

Living in an Early Tudor Castle: Households, Display, and Space, 1485-1547 Audrey Maria Thorstad Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of History November 2015 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Audrey Maria Thorstad to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Audrey Maria Thorstad 3 Acknowledgements The last four years of this research would not have been possible without the immense support form a great number of people. I must firstly thank my supervisors – past and present – all who have supported, challenged, and encouraged me along the way. To my current supervisors, Professor Emilia Jamzoriak and Axel Müller, a huge thank you is due. They have been endlessly helpful, critical, and whose insight helped to bring this project to fruition. Further thanks to Dr Paul Cavill who told me to ‘jump in with both feet’, which I have done and have not looked back since. I must also thank Professor Stephen Alford, whose knowledge on the Tudor period is infinite and whose support is much appreciated. Last, but certainly not least, my appreciation goes out to Kate Giles who helped make the viva experience a little less scary and a lot more fun. -

The Archaeology of Castle Slighting in the Middle Ages

The Archaeology of Castle Slighting in the Middle Ages Submitted by Richard Nevell, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology in October 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ……………………………………………………………………………… Abstract Medieval castle slighting is the phenomenon in which a high-status fortification is demolished in a time of conflict. At its heart are issues about symbolism, the role of castles in medieval society, and the politics of power. Although examples can be found throughout the Middle Ages (1066–1500) in England, Wales and Scotland there has been no systematic study of the archaeology of castle slighting. Understanding castle slighting enhances our view of medieval society and how it responded to power struggles. This study interrogates the archaeological record to establish the nature of castle slighting: establishing how prevalent it was chronologically and geographically; which parts of castles were most likely to be slighted and why this is significant; the effects on the immediate landscape; and the wider role of destruction in medieval society. The contribution of archaeology is especially important as contemporary records give little information about this phenomenon. Using information recovered from excavation and survey allows this thesis to challenge existing narratives about slighting, especially with reference to the civil war between Stephen and Matilda (1139–1154) and the view that slighting was primarily to prevent an enemy from using a fortification. -

An Interim Report EXCAVATIONS AT

CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY 34 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2013 An Interim Report By O. Davis & N. Sharples CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 34 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2013 Interim Report by O. Davis & N. Sharples with contributions by M. Allen & J. Jones CARDIFF STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY SPECIALIST REPORT NUMBER 34 EXCAVATIONS AT CAERAU HILLFORT, CARDIFF, SOUTH WALES, 2013 National Primary Reference Number (NPRN) 94517 Cadw Scheduled Ancient Monument No. GM018 Cardiff Studies in Archaeology Specialist Report 34 © The authors 2014 Oliver Davis and Niall Sharples, ISBN 978-0-9568398-3-1 Published by the Department of Archaeology & Conservation School of History Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University, Humanities Building, Colum Drive, Cardiff, CF10 3EU Tel: +44 (0)29 208 74470 Fax: +44 (0)29 208 74929 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission of the authors. Designed by Cardiff Archaeological Illustration and Design Software: Adobe Creative Suite 6 Design Premium Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 2 3. Previous Archaeological Work 6 4. Project Aims & Objectives 11 5. Excavation Methodology 14 6. Excavation Results 15 7. Finds 40 8. Palaeo - Environmental Summary 43 9. Summary 55 10. Community Impact 57 11. Bibliography 62 Appendix 1- Context Lists 65 Appendix 2 - Small Find List 73 Appendix 3 - Sample List 76 1. Introduction Excavations were undertaken from 24 June to 19 July The interior of the hillfort is privately owned and we are 2013 across the interior of Caerau Hillfort, Cardiff, very grateful to Mr Ralph David of Penylan Farm for directly over three of the evaluation trenches opened by permission to carry out the investigations. -

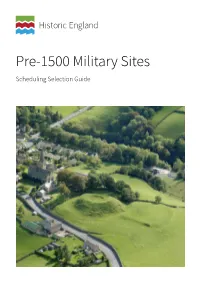

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s scheduling selection guides help to define which archaeological sites are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. For archaeological sites and monuments, they are divided into categories ranging from Agriculture to Utilities and complement the listing selection guides for buildings. Scheduling is applied only to sites of national importance, and even then only if it is the best means of protection. Only deliberately created structures, features and remains can be scheduled. The scheduling selection guides are supplemented by the Introductions to Heritage Assets which provide more detailed considerations of specific archaeological sites and monuments. This selection guide offers an overview of archaeological monuments or sites designed to have a military function and likely to be deemed to have national importance, and sets out criteria to establish for which of those scheduling may be appropriate. The guide aims to do two things: to set these sites within their historical context, and to give an introduction to some of the overarching and more specific designation considerations. This document has been prepared by Listing Group. It is one is of a series of 18 documents. This edition published by Historic England July 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Pre-1500 Military Sites: Scheduling Selection Guide. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ Front cover The castle at Burton-in-Lonsdale, North Yorkshire was built around 1100 as a ringwork; later it was reconstructed as a motte with two baileys.