COMMUNICATION Subadult Oxybelis Aeneus 1.5 M)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

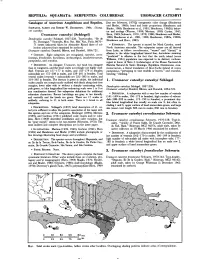

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Auto Guia Version Ingles

Parque Natural Metropolitano Tel: (507) 232-5516/5552 Fax: (507) 232-5615 www.parquemetropolitano.org Ave. Juan Pablo II final P.O. Box 0843-03129 Balboa, Ancón, Panamá República de Panamá 2 Taylor, L. 2006. Raintree Nutrition, Tropical Plant Database. http://www.rain- Welcome to the Metropolitan Natural Park, the lungs of Panama tree.com/plist.htm. Date accessed; February 2007 City! The park was established in 1985 and contains 232 hectares. It is one of the few protected areas located within the city border. Thomson, L., & Evans, B. 2006. Terminalia catappa (tropical almond), Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources You are about to enter an ecosystem that is nearly extinct in Latin (PAR), Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). http://www.traditionaltreeorg . Date accessed March America: the Pacific dry forests. Whether your goals for this walk 2007-04-23 are a simple walk to keep you in shape or a careful look at the forest and its inhabitants, this guide will give you information about Young, A., Myers, P., Byrne, A. 1999, 2001, 2004. Bradypus variegatus, what can be commonly seen. We want to draw your attention Megalonychidae, Atta sexdens, Animal Diversity Web. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bradypus_var toward little things that may at first glance seem hidden away. Our iegatus.html. Date accessed March 2007 hope is that it will raise your curiosity and that you’ll want to learn more about the mysteries that lie within the tropical forest. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The contents of this book include tree identifications, introductions Text and design: Elisabeth Naud and Rudi Markgraf, McGill University, to basic ecological concepts and special facts about animals you Montreal, Canada. -

Volume 4 Issue 1B

Captive & Field Herpetology Volume 4 Issue 1 2020 Volume 4 Issue 1 2020 ISSN - 2515-5725 Published by Captive & Field Herpetology Captive & Field Herpetology Volume 4 Issue1 2020 The Captive and Field Herpetological journal is an open access peer-reviewed online journal which aims to better understand herpetology by publishing observational notes both in and ex-situ. Natural history notes, breeding observations, husbandry notes and literature reviews are all examples of the articles featured within C&F Herpetological journals. Each issue will feature literature or book reviews in an effort to resurface past literature and ignite new research ideas. For upcoming issues we are particularly interested in [but also accept other] articles demonstrating: • Conflict and interactions between herpetofauna and humans, specifically venomous snakes • Herpetofauna behaviour in human-disturbed habitats • Unusual behaviour of captive animals • Predator - prey interactions • Species range expansions • Species documented in new locations • Field reports • Literature reviews of books and scientific literature For submission guidelines visit: www.captiveandfieldherpetology.com Or contact us via: [email protected] Front cover image: Timon lepidus, Portugal 2019, John Benjamin Owens Captive & Field Herpetology Volume 4 Issue1 2020 Editorial Team Editor John Benjamin Owens Bangor University [email protected] [email protected] Reviewers Dr James Hicks Berkshire College of Agriculture [email protected] JP Dunbar -

Download Download

Phyllomedusa 20(1):89–92, 2021 © 2021 Universidade de São Paulo - ESALQ ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v20i1p89-92 Short CommuniCation Dietary records for Oxybelis rutherfordi (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Trinidad and Tobago Renoir J. Auguste,1 Jason-Marc Mohamed,2 Marie-Elise Maingot,1 and Kyle Edghill3 1 Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies. St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. E-mail: renguste@ gmail.com. 2 Palmiste, Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. 3 D’Abadie, Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. Keywords: diet, island ecology, lizards, predator-prey relationship, Rutherford’s vine snake. Palavras-chave: dieta, ecologia de ilhas, relação predador-presa, serpente-arborícola-de-rutherford. SnaKes feed on a variety of prey (Greene islands of Trinidad and Tobago (Jadin et al. 1983). The diet of the Brown Vine SnaKe, 2020). Jadin et al. (2019) recognized that O. Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler, 1824), is well Known; rutherfordi is distinct from O. aeneus and lizards are the most common prey. This species described the species (Jadinet al. 2020). Because has no apparent taxonomic proclivity in its previous natural history information for O. dietary choices, which suggests that their rutherfordi was combined with O. aeneus selection of lizards is random (Mesquita et al. (Murphy et al. 2018), it is appropriate to provide 2012, Sousa et al. 2020). However, reports on new information for O. rutherfordi. the diet of Rutherford’s Vine Snake, Oxybelis Three separate predation events by O. rutherfordi Jadin, Blair, OrlofsKe, Jowers, rutherfordi were observed in January and Rivas, Vitt, Ray, Smith, and Murphy, 2020, are February 2021 involving three lizard species on limited (Murphy et al. -

Predation Attempt by Oxybelis Aeneus(Wagler)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Firenze University Press: E-Journals Acta Herpetologica 5(1): 19-22, 2010 Predation attempt by Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler) (Mexican Vine- snake) on Basiliscus plumifrons (Cope) Paul B.C. Grant1, Todd R. Lewis 2 1 4901 Cherry Tree Bend, Victoria B. C., V8Y 1SI, Canada. 2 Westfield, 4 Worgret Road, Wareham, Dorset, BH20 4PJ, UK. Corresponding author. E-mail: ecolewis@ gmail.com Submitted on: 2009, 31st August; revised on: 2010, 3rd March; accepted on: on2010, 13th March. Oxybelis aeneus is a broadly distributed vine snake of the New World (Keiser, 1982; Savage, 2002). Its enormous range stretches from Arizona and southern Texas, through Mexico, Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and into South America where it is found in Colombia, Ecuador, north-western Peru on the Pacific ver- sant, and as far south as Brazil and Bolivia on the Atlantic versant (Keiser, 1974, 1982; Dixon and Soini, 1986; Keiser, 1991; Pérez-Santos and Moreno, 1991; Lehr et al., 2002; Savage, 2002; Hernandez, 2004; Uetz, 2006; Cisneros-Heredia and Touzet, 2007; AGFD, 2008). It is also found on Trinidad and Tobago and other islands such as offshore atolls around Belize (Campbell, 1998; Platt et al., 2002). O. aeneus is easily recognised from other Oxybelis sp. vine snakes by its light-grey dorsum and black mouth lining. It is a common colubrid snake within its range, inhabit- ing open areas, grassland with scrub, forest edges, clearings within forest, abandoned pas- tures, riparian premontane wet forest, premontane rain forest, in addition to lowland wet and dry forest (Franzen, 1996; Savage, 2002). -

THE ORIGIN and EVOLUTION of SNAKE EYES Dissertation

CONQUERING THE COLD SHUDDER: THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF SNAKE EYES Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christopher L. Caprette, B.S., M.S. **** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Thomas E. Hetherington, Advisor Approved by Jerry F. Downhower David L. Stetson Advisor The graduate program in Evolution, John W. Wenzel Ecology, and Organismal Biology ABSTRACT I investigated the ecological origin and diversity of snakes by examining one complex structure, the eye. First, using light and transmission electron microscopy, I contrasted the anatomy of the eyes of diurnal northern pine snakes and nocturnal brown treesnakes. While brown treesnakes have eyes of similar size for their snout-vent length as northern pine snakes, their lenses are an average of 27% larger (Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.042). Based upon the differences in the size and position of the lens relative to the retina in these two species, I estimate that the image projected will be smaller and brighter for brown treesnakes. Northern pine snakes have a simplex, all-cone retina, in keeping with a primarily diurnal animal, while brown treesnake retinas have mostly rods with a few, scattered cones. I found microdroplets in the cone ellipsoids of northern pine snakes. In pine snakes, these droplets act as light guides. I also found microdroplets in brown treesnake rods, although these were less densely distributed and their function is unknown. Based upon the density of photoreceptors and neural layers in their retinas, and the predicted image size, brown treesnakes probably have the same visual acuity under nocturnal conditions that northern pine snakes experience under diurnal conditions. -

A New Vine Snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and Redescription of O

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2021 A new vine snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and redescription of O. acuminatus Robert C. Jadin University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire Michael J. Jowers Universidade do Porto Sarah A. Orlofske University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire William E. Duellman University of Kansas Christopher Blair CUNY New York City College of Technology See next page for additional authors How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/685 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Authors Robert C. Jadin, Michael J. Jowers, Sarah A. Orlofske, William E. Duellman, Christopher Blair, and John C. Murphy This article is available at CUNY Academic Works: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/685 Evolutionary Systematics. 5 2021, 1–12 | DOI 10.3897/evolsyst.5.60626 A new vine snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and redescription of O. acuminatus Robert C. Jadin1, Michael J. Jowers2, Sarah A. Orlofske1, William E. Duellman3, Christopher Blair4,5, John C. Murphy6,7 1 Department of Biology and Museum of Natural History, University of Wisconsin Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI 54481, USA 2 CIBIO/InBIO (Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos), Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrario De Vairão, 4485- 661, Vairão, Portugal 3 Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7593, USA 4 Department of Biological Sciences, New York City College of Technology, The City University of New York, 285 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 112015, USA 5 Biology PhD Program, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave., New York, NY 10016, USA 6 Science and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. -

Hiding in the Lianas of the Tree of Life Molecular Phylogenetics And

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 134 (2019) 61–65 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Hiding in the lianas of the tree of life: Molecular phylogenetics and species T delimitation reveal considerable cryptic diversity of New World Vine Snakes ⁎ Robert C. Jadina, , Christopher Blairb,c, Michael J. Jowersd, Anthony Carmonaa, John C. Murphye,1 a Department of Biology, Northeastern Illinois University, 5500 North St., Louis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60625-4699, USA b Department of Biological Sciences, New York City College of Technology, The City University of New York, 285 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 1120, USA c Biology PhD Program, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave., New York, NY 10016, USA d CIBIO/InBIO (Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos), Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrario De Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal e Science and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Brown Vine Snake, Oxybelis aeneus, is considered a single species despite the fact its distribution covers an Bayesian estimated 10% of the Earth’s land surface, inhabiting a variety of ecosystems throughout North, Central, and Biodiversity South America and is distributed across numerous biogeographic barriers. Here we assemble a multilocus mo- Oxybelis lecular dataset (i.e. cyt b, ND4, cmos, PRLR) derived from Middle American populations to examine for the first RASP time the evolutionary history of Oxybelis and test for evidence of cryptic lineages using Bayesian and maximum Reptilia likelihood criteria. Our divergence time estimates suggest that Oxybelis diverged from its sister genus, Leptophis, Serpentes approximately 20.5 million years ago (Ma) during the lower-Miocene. -

A Monographic Study of the Neotropical Vine Snake, Oxybelis Aeneus (Wagler)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 A Monographic Study of the Neotropical Vine Snake, Oxybelis Aeneus (Wagler). Edmund Davis Keiser Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Keiser, Edmund Davis Jr, "A Monographic Study of the Neotropical Vine Snake, Oxybelis Aeneus (Wagler)." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1342. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1342 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-17,325 KEISER, Jr., Edmund Davis, 1934- A MONOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE NEOTROPICAL VINE SNAKE, Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler). Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical CoUege, Ph.D,, 1967 Zoology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A MONOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE NEOTROPICAL VINE SNAKE, Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler) A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Zoology by Edmund Davis Keiser, Jr. M.S., Southern Illinois University, 1961 August, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to the following persons for the loan of specimens, for advice or information, or for other assistance during this investigation: Dr. S. C. Anderson, Dr. J. Anthony, Dr. -

Predation of a Utila Spiny-Tailed Iguana, Ctenosaura Bakeri (Iguanidae), by a Central American Boa, Boa Imperator (Boidae), on Utila, Isla De La Bahia, Honduras

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342339312 Predation of a Utila Spiny-tailed Iguana, Ctenosaura bakeri (Iguanidae), by a Central American Boa, Boa imperator (Boidae), on Utila, Isla de la Bahia, Honduras Article · August 2020 CITATIONS READS 0 34 3 authors: Daisy Maryon Tom Brown University of South Wales Kanahau Utila Research & Conservation Facility 15 PUBLICATIONS 8 CITATIONS 58 PUBLICATIONS 33 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE David C. Lee University of South Wales 17 PUBLICATIONS 211 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ecological studies on the Critically Endangered Utila Spiny-tailed Iguana in Honduras View project Herpetofauna of Cusuco National Park, Honduras View project All content following this page was uploaded by Tom Brown on 02 August 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. WWW.IRCF.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 27(2):265–266 • AUG 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Predation. Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis of catenifer a sayi ) inUtila Wisconsin: Spiny-tailed Iguana, On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 Ctenosaura. The Shared History of Treeboas bakeri (Corallus grenadensis ) (Iguanidae),and Humans on Grenada: by a Central A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 AmericanRESEARCH ARTICLES Boa, Boa imperator (Boidae), . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . -

PDF Files Before Requesting Examination of Original Lication (Table 2)

often be ingested at night. A subsequent study on the acceptance of dead prey by snakes was undertaken by curator Edward George Boulenger in 1915 (Proc. Zool. POINTS OF VIEW Soc. London 1915:583–587). The situation at the London Zoo becomes clear when one refers to a quote by Mitchell in 1929: “My rule about no living prey being given except with special and direct authority is faithfully kept, and permission has to be given in only the rarest cases, these generally of very delicate or new- Herpetological Review, 2007, 38(3), 273–278. born snakes which are given new-born mice, creatures still blind and entirely un- © 2007 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles conscious of their surroundings.” The Destabilization of North American Colubroid 7 Edward Horatio Girling, head keeper of the snake room in 1852 at the London Zoo, may have been the first zoo snakebite victim. After consuming alcohol in Snake Taxonomy prodigious quantities in the early morning with fellow workers at the Albert Public House on 29 October, he staggered back to the Zoo and announced that he was inspired to grab an Indian cobra a foot behind its head. It bit him on the nose. FRANK T. BURBRINK* Girling was taken to a nearby hospital where current remedies available at the time Biology Department, 2800 Victory Boulevard were tried: artificial respiration and galvanism; he died an hour later. Many re- College of Staten Island/City University of New York spondents to The Times newspaper articles suggested liberal quantities of gin and Staten Island, New York 10314, USA rum for treatment of snakebite but this had already been accomplished in Girling’s *Author for correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] case. -

Snake Communities Worldwide

Web Ecology 6: 44–58. Testing hypotheses on the ecological patterns of rarity using a novel model of study: snake communities worldwide L. Luiselli Luiselli, L. 2006. Testing hypotheses on the ecological patterns of rarity using a novel model of study: snake communities worldwide. – Web Ecol. 6: 44–58. The theoretical and empirical causes and consequences of rarity are of central impor- tance for both ecological theory and conservation. It is not surprising that studies of the biology of rarity have grown tremendously during the past two decades, with particular emphasis on patterns observed in insects, birds, mammals, and plants. I analyse the patterns of the biology of rarity by using a novel model system: snake communities worldwide. I also test some of the main hypotheses that have been proposed to explain and predict rarity in species. I use two operational definitions for rarity in snakes: Rare species (RAR) are those that accounted for 1% to 2% of the total number of individuals captured within a given community; Very rare species (VER) account for ≤ 1% of individuals captured. I analyse each community by sample size, species richness, conti- nent, climatic region, habitat and ecological characteristics of the RAR and VER spe- cies. Positive correlations between total species number and the fraction of RAR and VER species and between sample size and rare species in general were found. As shown in previous insect studies, there is a clear trend for the percentage of RAR and VER snake species to increase in species-rich, tropical African and South American commu- nities. This study also shows that rare species are particularly common in the tropics, although habitat type did not influence the frequency of RAR and VER species.