Changing Targets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air and Space Power Journal: Winter 2009

SPINE AIR & SP A CE Winter 2009 Volume XXIII, No. 4 P OWER JOURN Directed Energy A Look to the Future Maj Gen David Scott, USAF Col David Robie, USAF A L , W Hybrid Warfare inter 2009 Something Old, Not Something New Hon. Robert Wilkie Preparing for Irregular Warfare The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be Col John D. Jogerst, USAF, Retired Achieving Balance Energy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency Col John B. Wissler, USAF US Nuclear Deterrence An Opportunity for President Obama to Lead by Example Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force 2009-4 Outside Cover.indd 1 10/27/09 8:54:50 AM SPINE Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck http://www.af.mil Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF, Retired Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Darlene H. Barnes, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the http://www.au.af.mil presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. -

Chasing Success

AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Chasing Success Air Force Efforts to Reduce Civilian Harm Sarah B. Sewall Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Sewall, Sarah B. Copy Editor Carolyn Burns Chasing success : Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm / Sarah B. Sewall. Cover Art, Book Design and Illustrations pages cm L. Susan Fair ISBN 978-1-58566-256-2 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Air power—United States—Government policy. Nedra O. Looney 2. United States. Air Force—Rules and practice. 3. Civilian war casualties—Prevention. 4. Civilian Print Preparation and Distribution Diane Clark war casualties—Government policy—United States. 5. Combatants and noncombatants (International law)—History. 6. War victims—Moral and ethical aspects. 7. Harm reduction—Government policy— United States. 8. United States—Military policy— Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. II. Title: Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm. UG633.S38 2015 358.4’03—dc23 2015026952 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Published by Air University Press in March 2016 Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes Design and Production Manager Cheryl King Air University Press 155 N. Twining St., Bldg. 693 Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 [email protected] http://aupress.au.af.mil/ http://afri.au.af.mil/ Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the organizations with which they are associated or the views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any AFRI other US government agency. -

Nuclear Futures: Western European Options for Nuclear Risk Reduction

Nuclear futures: Western European options for nuclear risk reduction Martin Butcher, Otfried Nassauer & Stephen Young British American Security Information Council and the Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS), December 1998 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations Executive Summary Chapter One: Nuclear Weapons and Nuclear Policy in Western Europe Chapter Two: The United Kingdom Chapter Three: France Chapter Four: Nuclear Co-operation Chapter Five: NATO Europe Chapter Six: Nuclear Risk Reduction in Western Europe Endnotes About the authors Martin Butcher is the Director of the Centre for European Security and Disarmament (CESD), a Brussels-based non-governmental organization. Currently, he is a Visiting Fellow at BASIC’s Washington office. Otfried Nassauer is the Director of the Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS). Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst as BASIC. Previously, he worked for 20/20 Vision and for ACCESS: A Security Information Service. He has a Masters in International Affairs from Columbia University, and a BA from Carleton College. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many people who pro-vided help of various kinds during the writing of this report. They include: Nicola Butler, for her inestimable assistance; Ambassador James Leonard, for his helpful comments on the report’s recommendations; Professors Paul Rogers and Patricia Chilton, for their comments on early drafts; Daniel Plesch, for his comments on the entire report; and Camille Grand, for his guidance and support in compiling the section on France. Special thanks to Lucy Amis and Tanya Padberg for excellent proofing and copy-editing work, and to Christine Kucia and Kate Joseph for advice and assistance on the layout and design of the report. -

The Long Search for a Surgical Strike Precision Munitions and the Revolution in Military Affairs

After you have read the research report, please give us your frank opinion on the contents. All comments––large or small, complimentary or caustic––will be gratefully appreciated. Mail them to CADRE/AR, Building 1400, 401 Chennault Circle, Maxwell AFB AL 36112–6428. The Long Search for Mets a Surgical Strike Precision Munitions and the Revolution in Military Affairs Cut along dotted line Thank you for your assistance ............................................................................................... ......... COLLEGE OF AEROSPACE DOCTRINE, RESEARCH AND EDUCATION AIR UNIVERSITY The Long Search for a Surgical Strike Precision Munitions and the Revolution in Military Affairs DAVID R. METS, PhD School of Advanced Airpower Studies CADRE Paper No. 12 Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6615 October 2001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mets, David R. The long search for a surgical strike : precision munitions and the revolution in military affairs / David R. Mets. p. cm. -- (CADRE paper ; no. 12) — ISSN 1537-3371 At head of title: College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education, Air University. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-58566-096-5 1. Air power--History. 2. Air power--United States. 3. Precision guided munitions-- History. 4. Precision guided munitions--United States. I. Title. II. CADRE paper ; 12. UG630 .M37823 2001 359'00973--dc21 2001045987 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not -

Air Force Strategic Planning: Past, Present, and Future

C O R P O R A T I O N Air Force Strategic Planning Past, Present, and Future Raphael S. Cohen For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1765 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9697-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface For a relatively young service, the U.S. Air Force has a remarkably rich intellectual history. Even before the Air Force’s official formation, the development of airpower has been dotted with such visionaries as Billy Mitchell and Henry “Hap” Arnold. -

The Vital Link the Tanker’S Role in Winning America’S Wars

AIR UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The Vital Link The Tanker’s Role in Winning America’s Wars DAVID M. COHEN Major, USAF Fairchild Paper Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6615 March 2001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cohen, David M., 1965– The vital link : the tanker’s role in winning America’s wars / David M. Cohen. p. cm. “Fairchild paper.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-088-4 1. KC-135 (Tanker aircraft). 2. Airtankers (Military science—United States. I. Title. UG1242.T36.C65 2001 358.4’183—dc21 00-054834 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. This Fairchild Paper, and others in the series, is available electronically at the Air University Research web site http://research.maxwell.af.mil under “Research Papers” then “Special Collections.” ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix ABSTRACT . xi RESEARCH STUDY LIMITATIONS . xiii 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Notes . 2 2 STRATOTANKER HISTORY: COLD WAR TO DESERT HEAT . 3 The Tanker Goes Tactical: Vietnam . 4 Refueling across a Line in the Sand: Desert Storm . 6 Notes . 8 3 AGING TANKERS COME OF AGE: RECENT TANKER EXPERIENCE . 11 Velocity Equals Distance over Time . 12 Damn the Boneyard: Full Speed Ahead! . 13 Allied Force: The Tanker Shines . 16 Notes . 19 4 KC-135 FORCE STRUCTURE: WHEN TO SAY WHEN . -

WINTER 2008 - Volume 55, Number 4 WINTER 2008 - Volume 55, Number 4

WINTER 2008 - Volume 55, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG WINTER 2008 - Volume 55, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG From Satellite Tracking to Space Situational Awareness: Features The USAF and Space Surveillance 1957-2007 Rick W. Sturdevant 4 Precision Aerial Bombardment of Strategic Targets: Its Rise, Fall, and Resurrection Daniel L. Haulman 24 Operation Just Cause: An Air Power Perspective Stetson M. Siler 34 The P–51 Mustang: The Most Important Aircraft in History? Marshall L. Michel 46 Book Reviews The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 By Rick Atkinson Reviewed by Curtis H. O’Sullivan 58 The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 By Rick Atkinson Reviewed by Grant T. Weller 58 Gunning for the Red Baron By Leon Bennett Reviewed by Carl A. Christie 58 Clash of Eagles: USAAF 8th Air Force Bombers versus the Luftwafffe in World War II By Martin W. Bowman Reviewed by Anthony E. Wessel 59 Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries that Ignited the Space Race By Matthew Brzezinski Reviewed by J. Ron Davis 59 Danger Close: Tactical Air Controllers in Afghanistan and Iraq By Steve Call Reviewed by David J. Schepp 60 A Tale of Two Quagmires: Iraq, Vietnam, and the Hard Lessons of War By Kenneth J. Campbell Reviewed by John L. Cirafici 60 Risk and Exploration: Earth, Sea, and the Stars By Steven J. Dick & Keith L. Cowing, Eds. Reviewed by Steven Pomeroy 61 Under the Guns of the Red Baron: Von Richtofen’s Victories and Victims Fully Illustrated By Norman Franks, et al. -

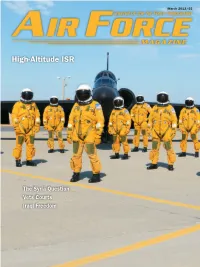

High-Altitude ISR

March 2013/$5 High-Altitude ISR The Syria Question Vets Courts Iraqi Freedom March 2013, Vol. 96, No. 3 Publisher Craig R. McKinley Editor in Chief Adam J. Hebert Editorial [email protected] Editor Suzann Chapman Executive Editors Michael C. Sirak John A. Tirpak Senior Editors Amy McCullough Marc V. Schanz Associate Editor Aaron M. U. Church Contributors Walter J. Boyne, John T. Correll, Robert 38 S. Dudney, Rebecca Grant, Peter Grier, Otto Kreisher, Anna Mulrine FEATURES Production [email protected] 4 Editorial: Leaving No One Behind Managing Editor By Adam J. Hebert Juliette Kelsey Chagnon Identifying Keller and Meroney was extraordinary—and typical. Assistant Managing Editor Frances McKenney 26 The Syria Question By John A. Tirpak Editorial Associate June Lee 46 An air war would likely be tougher than what the US saw in Serbia or Senior Designer Libya. Heather Lewis 32 Spy Eyes in the Sky Designer By Marc V. Schanz Darcy N. Lewis The long-term futures for the U-2 and Global Hawk are uncertain, but for Photo Editor now their unique capabilities remain Zaur Eylanbekov in high demand. Production Manager 38 Iraqi Freedom and the Air Force Eric Chang Lee By Rebecca Grant The Iraq War changed the Air Force Media Research Editor in ways large and small. Chequita Wood 46 Strike Eagle Rescue Advertising [email protected] By Otto Kreisher The airmen were on the ground Director of Advertising in Libya, somewhere between the William Turner warring loyalists and the friendly 1501 Lee Highway resistance. Arlington, Va. 22209-1198 Tel: 703/247-5820 52 Remote and Ready at Kunsan Telefax: 703/247-5855 Photography by Jim Haseltine About the cover: U-2 instructor pilots at North Korea is but a short flight away. -

Abcs of Leadership

2019, VOLUME 2 NUMBER 2 A LEGACY SERIES ABCs of Leadership George Lee Butler, Gen (ret), USAF USAFA, Class of 1961 CENTER FOR CHARACTER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT EDITORIAL STAFF: EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. Mark Anarumo, Dr. David Altman, Center for Creative Managing Editor, Colonel, USAF Leadership Dr. Douglas Lindsay, Dr. Marvin Berkowitz, University of Missouri- Editor in Chief, USAF (Ret) St. Louis Dr. John Abbatiello, Dr. Dana Born, Harvard University Book Review Editor, USAF (Ret) (Brig Gen, USAF, Retired) Dr. David Day, Claremont McKenna College Ms. Julie Imada, Editor & CCLD Strategic Dr. Shannon French, Case Western Communications Chief Dr. William Gardner, Texas Tech University JCLD is published at the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Mr. Chad Hennings, Hennings Management Colorado. Articles in JCLD may be Corp reproduced in whole or in part without permission. A standard source credit line Mr. Max James, American Kiosk is required for each reprint or citation. Management For information about the Journal of Dr. Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University Character and Leadership Development or the U.S. Air Force Academy’s Center Dr. Robert Kelley, Carnegie Mellon for Character and Leadership University Development or to be added to the Association of Graduates Journal’s electronic subscription list, Ms. Cathy McClain, (Colonel, USAF, Retired) contact us at: Dr. Michael Mumford, University of [email protected] Oklahoma Phone: 719-333-4904 Dr. Gary Packard, United States Air Force Academy (Colonel, USAF) The Journal of Character & Leadership Development Dr. George Reed, University of Colorado at The Center for Character & Leadership Colorado Springs (Colonel, USA, Retired) Development Rice University U.S. -

The Future of Airpower in the Aftermath of the Gulf

The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War Edited by Richard H. Shultz, Jr. Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. International Security Studies Program The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Tufts University Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-5532 July 1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Future of air power in the aftermath of the Gulf War/edited by Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Richard H. Shultz, Jr. p. cm. Includes index. 1. Air power-United States-Congresses . 2. United States. Air Force-Congresses . 3. Persian Gulf War. 1991-Aerial operations, American-Congresses . I. Pfaltzgraff, Robert L. II. Shultz, Richard H., 1947-. UG633. F86 1992 92-8181 358.4'03'0973-dc20 CIP ISBN 1-58566-046-9 First Printing July 1992 Second Printing June 1995 Third Printing August 1997 Fourth Printing August 1998 Fifth Printing March 2001 Sixth Printing July 2002 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the editors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . vii PREFACE . ix PART I Strategic Factors Reshaping Strategies and Missions Introduction . 3 Air Power in the New Security Environment . 9 Secretary of the Air Force Donald B . Rice Air Power in US Military Strategy . 17 Dr Edward N. Luttwak The United States as an Aerospace Power in the Emerging Security Environment . 39 Dr Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. Employing Air Power in the Twenty-first Century . -

George Lee Butler Class of 1961

George Lee Butler Class of 1961 DISPLAYED ON THE WALLS of Gen. (Ret.) George Lee Butler’s garage are plaques, honors and memorabilia from a life well lived. His wife, Dorene, calls it the “Butler Museum.” But it’s not the only room in the Laguna Beach, California, home dedicated to reminders of Butler’s path from USAFA cadet to even- tual four-star general responsible for the nation’s nuclear arsenal. On shelves in the family room are displayed a progression of headgear worn by Butler ’61 throughout his military career — his dress whites cadet hat, his pilot helmet and his Air Force offi- cer’s hat from his years of career advancement. In the living room, an impressive Oriental display cabinet protects a delicate piece of glassware given the Butlers by former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Elsewhere in the house, family pictures, historic artifacts, mili- tary medals and books tracing the history of our nation’s military are on full display. It’s interesting to note that the collection of memorabilia may never have been assembled — including the medal Gen. Butler is about to receive as a 2016 Distinguished Graduate of USAFA — if it were not for the investment of just two bits 50 years ago. Opportunity Knocks The son of a career Army soldier, Butler was used to the nomadic lifestyle of a military brat. Whenever his father was deployed overseas, including during World War II and Korea, the Butlers would retreat to the small town of Oak- land, Mississippi, to live with relatives. Educational and athletic opportunities in the rural com- munity were sparse, as Butler grappled with what his future would hold. -

I NUCLEAR WEAPONS AFTER the COLD WAR: CHANGE and CONTINUITY IN

NUCLEAR WEAPONS AFTER THE COLD WAR: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN PUBLIC DISCOURSES by David Cram Helwich Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Science, University of Wyoming, 1997 Master of Arts, University of Wyoming, 2000 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of College of Liberal Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by David Cram Helwich It was defended on January 24, 2011 and approved by William Keller, PhD, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs John Lyne, PhD, Professor, Communication John Poulakos, PhD, Associate Professor, Comunication Dissertation Advisor: Gordon Mitchell, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication ii Copyright © by David Cram Helwich 2011 iii NUCLEAR WEAPONS AFTER THE COLD WAR: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN PUBLIC DISCOURSES David Cram Helwich, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation assesses the rhetorical dynamics of American public argumentation about the appropriate role of nuclear weapons since the end of the Cold War. Four case studies are examined, including the controversy created by “fallen priests” like General George Lee Butler, the U.S. Senate’s deliberations on ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, the George W. Bush administration’s campaign to implement its 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, and the public debate about the development and deployment of “mini” nuclear weapons. Collectively, the case studies reveal that a potent combination of institutional interests, restricted access to official deliberative spaces, the deployment of threat discourses, the presumption that nuclear deterrence was effective during the Cold War, and the utilization of technical discursive practices narrowed the scope of public debate about the role of nuclear weapons and allowed advocates of robust nuclear deterrence to construct rhetorical and policy bridges between the Cold War and post-Cold War eras.