Bridging Gaps and Building Opportunities: Reflections on My Experience of Engaging in Community Development in Azena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Impact of Khat Production on Household Welfare in Amhara Region of Ethiopia

Impact of khat production on household welfare in Amhara region of Ethiopia by Hanna Lynn Ruder B.S., Kansas State University, 2016 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Agricultural Economics College of Agriculture KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2018 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Benjamin Schwab Copyright © Hanna Ruder 2018. Abstract Khat, a lucrative cash crop cultivated in and near the Horn of Africa, is gaining the interest of researchers around the globe. Despite its potential to provide excess income, economic opportunity, and access to technology to those who produce it, the conflicting legal status around the globe causes policy and trade disputes between countries. Research on the impact of khat production on household welfare is sparse. To address this, the purpose of this research is to determine what factors affect the decision to grow khat and subsequently determine the impact of khat production on labor, income, education expenditure, and food security. Data was extracted from a survey conducted in early 2017. A total of 365 households in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia were surveyed. We estimate the factors affecting the decision to grow khat by employing use of two logit models and one linear probability model to calculate marginal effects. We estimate the impact of khat production on labor, income, education expenditure, and food security through propensity score matching. Khat production appears to be adopted by households who are educated and apt to adopt improved technologies. These households are likely to own a donkey, own irrigation, and own more plots than a non-producing household. -

Report and Opinion 2017;9(7) 60

Report and Opinion 2017;9(7) http://www.sciencepub.net/report Community Based Knowledge, Attitude And Practice Of Rabies In Injibara Town And Its Surroundings, Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, North-Western Ethiopia Yigardush Wassihune1, Melese Yenew1, Ayalew Niguse2 1 College of Veterinary Medicine, Jigjiga University, P.O. Box.1020, Jigjiga, Ethiopia. 2Lecturer at Jigjiga university, College of Veterinary Medicine, Jigjiga University, P.O. Box.1020, Jigjiga, Ethiopia. [email protected] Abstract: Rabies is a viral disease of all warm blooded animals, which causes acute fatal encephalitis, with almost 100% case fatality rate. It is caused by rabies virus (genus Lyssa virus) which is mainly transmitted by rabid animal bites. This disease occurs in more than 150 countries and territories and about 55,000 people die of rabies every year, mostly in developing world despite that it is preventable disease by vaccination. Ethiopia is highly endemic for rabies; yet, a nationwide data on rabies has not been gathered to reveal the actual magnitude of the problem and public awareness levels. With a conviction that a handful of works on public knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) in rabies be done to plan, execute any control and/or eradication programs, this study was conducted in Injibara town and its surroundings from November, 2015 to April, 2016 to assess the knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) on rabies and related factors. The design was: ccommunity-based retrospective, quantitative study design to assess the KAP on rabies and related factors. The entire three kebeles of the town and its surrounding rural kebeles were considered in the study. -

Debre Markos-Gondar Road

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ethiopian Roads Authority , / International Development Association # I VoL.5 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS OF THE FIVE Public Disclosure Authorized ROADS SELECTED FOR REHABILITATION AND/OR UPGRADING DEBRE MARKOS-GONDAR ROAD # J + & .~~~~~~~~i-.. v<,,. A.. Public Disclosure Authorized -r~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ - -':. a _- ..: r. -. * .. _, f_ £ *.. "''" Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report October 1997 [rJ PLANCENTERLTD Public Disclosure Authorized FYi Opastinsilta6, FIN-00520HELSINKI, FINLAND * LJ Phone+358 9 15641, Fax+358 9 145 150 EA Report for the Debre Markos-Gondar Road Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................... i ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................... iv GENERALMAP OF THE AREA ........................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................... vi I. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Location of the StudyArea. 1 1.3 Objectiveof the Study. 1 1.4 Approachand Methodologyof the Study. 2 1.5 Contentsof the Report. 3 2. POLICY,LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONALFRAMEWORK ....... 4 2.1 Policy Framework..Framewor 4 2.2 Legal Framework..Framewor 6 2.3 InstitutionalFramework. .Framewor 8 2.4 Resettlement and Compensation .12 2.5 Public Consultation 15 3. DESCRIPTIONOF THE PROPOSEDROAD PROJECT........... 16 4. BASELINEDATA ............. ........................... 18 4.1 Descriptionof the Road.18 4.2 Physical Environment nvironmt. 20 4.2.1 Climate and hydrology ................. 20 4.2.2 Physiography ............ ....... 21 4.2.3 Topography and hydrography ............ 21 4.2.4 Geology ....... ............ 21 4.2.5 Soils and geomorphology ................ 21 4.3 BiologicalEnvironment......................... 22 4.3.1 Land use and land cover .22 4.3.2 Flora .22 4.3.3 Fauna .22 4.4 Human and Social Environent .23 4.4.1 Characteristics of the population living by/alongthe road ..................... -

Of Maize Markets in Case of Alefa District Northwestern Ethiopia

Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8451 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.70, 2020 Analyze Structure, Conduct, and Performance (SCP) of Maize Markets in Case of Alefa District Northwestern Ethiopia Abera Ayalew 1* Fentahun Tesafa 2 Zewdu Berhanie 2 1.Department of Agricultural Economics, Woldia University, Woldia, Ethiopia 2.Department of Agricultural Economics, Bahir dar University, Bahir dar, Ethiopia Abstract This study examined the major market channels, and evaluate the market margins for key maize marketing channels in Alefa District, Central Gondar Zone of Amhara Regional State. Both primary and secondary data sources for the study were collected. Primary data were collected through personal interviews from a total of 198 producers and 34 traders. Descriptive statistics was employed to describe the socio-economic characteristics of farm households, and to analyze market related data collected from maize traders. The results show that wholesalers and rural assemblers are the most important buyers of maize from producers, accounting for 44 and 36.35% respectively. Market concentration ratio of 74.07% indicates that the maize market in the study area is characterized as oligopolistic. The result of the study also showed that, maize average production and yield were 18.03 quintals per household and 34.37 quintals per hectare, respectively. The major constraints for maize production and marketing of households in the study area include high price of fertilizers, timely availability of improved seeds, large number of unlicensed traders in the markets, climate change (occurrence of drought, pest/diseases), availability of credit access and non-transparent taxation system. -

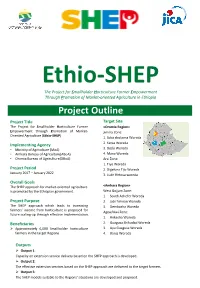

Ethio-SHEP Project Outline

Ethio-SHEP The Project for Smallholder Horticulture Farmer Empowerment Through Promotion of Market-oriented Agriculture in Ethiopia Project Outline Project Title Target Site The Project for Smallholder Horticulture Farmer <Oromia Region> Empowerment through Promotion of Market- Jimma Zone: Oriented Agriculture (Ethio-SHEP) 1. Seka chokorsa Woreda Implementing Agency 2. Kersa Woreda • Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 3. Dedo Woreda • Amhara Bureau of Agriculture(ABoA) 4. Mana Woreda • Oromia Bureau of Agriculture(OBoA) Arsi Zone: 1. Tiyo Woreda Project Period 2. Digeluna Tijo Woreda January 2017 – January 2022 3. Lude Hetosa woreda Overall Goals The SHEP approach for market-oriented agriculture <Amhara Region> is promoted by the Ethiopian government. West Gojjam Zone: 1. South Achefer Woreda Project Purpose 2. Jabi Tehnan Woreda The SHEP approach which leads to increasing 3. Dembacha Woreda farmers' income from horticulture is proposed for Agew/Awi Zone: future scaling-up through effective implementation. 1. Ankesha Woreda Beneficiaries 2. Guagusa Shikudad Woreda ➢ Approximately 6,000 Smallholder horticulture 3. Ayu Guagusa Woreda farmers in the target Regions 4. Banja Woreda Outputs ➢ Output 1: Capacity on extension service delivery based on the SHEP approach is developed. ➢ Output 2: The effective extension services based on the SHEP approach are delivered to the target farmers. ➢ Output 3: The SHEP models suitable to the Regions' situations are developed and proposed. Concept of SHEP Approach Promoting “Farming as a Business” Empowering and motivating people Sharing information among market actors & farmers for Three psychological needs to motivate people improving efficiency of local economies Autonomy Market Info. People need to feel in control of (variety, price, Market their own behaviors and goals season, etc.) Family budgeting Survey by Farmers farmers Competence Sharing SHEP People need to gain mastery market Linkage of tasks and learn different information forum skills Relatedness Market actors Producer Info. -

Impact of Pollinator Habitats and Managed Bee Pollination on Yields of Pollinator Dependent Crops, Evidence from North West Ethiopia

DSpace Institution DSpace Repository http://dspace.org Soil Science Thesis and Dissertations 2019-01-02 IMPACT OF POLLINATOR HABITATS AND MANAGED BEE POLLINATION ON YIELDS OF POLLINATOR DEPENDENT CROPS, EVIDENCE FROM NORTH WEST ETHIOPIA: SISAY GETAHUN http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/9257 Downloaded from DSpace Repository, DSpace Institution's institutional repository BAHIR DAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IMPACT OF POLLINATOR HABITATS AND MANAGED BEE POLLINATION ON YIELDS OF POLLINATOR DEPENDENT CROPS, EVIDENCE FROM NORTH WEST ETHIOPIA: M.SC. THESIS BY SISAY GETAHUN October, 2018 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia BAHIR DAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IMPACT OF POLLINATOR HABITATS AND MANAGED BEE POLLINATION ON YIELDS OF POLLINATOR DEPENDENT CROPS, EVIDENCE FROM NORTH WEST ETHIOPIA: M.SC. THESIS BY SISAY GETAHUN SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (M.SC.) IN AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS October, 2018 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia i Bahir Dar University College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences APPROVAL SHEET As member of the Board of Examiners of the Master of Sciences (M.Sc.) thesis open defense examination, we have read and evaluated this thesis prepared by Miss. Sisay Getahun entitled Impact of Pollinator Habitats and Managed Bee Pollination on Yields of Pollinator Dependent Crops in: North Western Ethiopia. We hereby certify that, the thesis is accepted for fulfilling the requirements for the award of the -

A Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in Ankesha District of Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia

Open Access Austin Journal of Veterinary Science & Animal Husbandry Research Article A Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in Ankesha District of Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia Adugna T1, Lamessa A2, Hailu S3, Habtamu T4 and Kebede B4* Abstract 1National Tsetse Flies and Trypanosomosis Investigation A cross- sectional study aimed at investigating the prevalence of and Control Center, Bedelle, Ethiopia Trypanosomosis was conducted in five selected peasant associations of 2Seyo livestock and Fisheries Development Office, Dembi Ankesha district, of Awi zone of North Western part of Ethiopia from November to Dollo, Ethiopia December 2016. A total of 384 blood samples were taken from marginal ear vein 3Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Development, Addis by puncturing with sterile lancet and dropping down in to heparinized capillary Ababa, Ethiopia tube to its 3/4th level after which it was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 12000rpm. 4Veterinary Drug and Feed Administration and Control This enhances to reveal the buffy coat at ease where Trypanosome is likely authority, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia concentrated and is the locus where to be cut by diamond pencil to be seen *Corresponding author: Bedaso Kebede, Veterinary under microscope for motility of Trypanosome species. Out of 384 samples only Drug and Feed Administration and Control Authority, 28 of them were found to be positive with an overall prevalence of 7.29%. The Addis Ababa, Ethiopia attribute of difference in peasant association, and host related risk factors (age, sex, body condition, PCV value) were expressed in detail with their degree of Received: April 09, 2017; Accepted: May 18, 2017; statistical significance for correlation with occurrence of Trypanosome species. -

In the West Amhara Sub-Region of Ethiopia

Journal of Plant Pathology (2011), 93 (1), 149-157 ' Edizioni ETS Pisa, 2011 149 INCIDENCE OF POTATO VIRUSES AND BACTERIAL WILT DISEASE IN THE WEST AMHARA SUB-REGION OF ETHIOPIA B. Bekelel, E. Abate2, A. Asefa2 and M. Dickinson3 I Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Plant Protection Research Centre, P.O. Box 37, Ambo, Ethiopia 2 Amhara Region Agricultural Research Institute, P.O. Box 527, Bahar Dar, Ethiopia 3 School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington Campus, Loughborough LE12 5RD, UK SUMMARY INTRODUCTION A survey of virus diseases and bacterial wilt was car- Ethiopia is among the top potato (Solanum tuberosum ried out in four major potato growing administrative L.) producers in Africa, with 70% of its arable land in the zones in the west Amhara sub-region of Ethiopia in high altitude areas above 1500 m being suitable for pota- 2008. Leaf samples with symptoms suggestive of virus to production (FAOSTAT, 2008). Currently, potato is infection were collected from 38 randomly selected produced mainly in the north western, central and east- fields in 16 locations, whilst for bacterial wilt detection ern highlands of Ethiopia. The north western part of the tuber and stem samples were collected from 23 and 12 country which mainly includes the highlands of the west fields in 15 and 12 locations, respectively. Disease inci- Amhara sub-region (Fig. 1) is the major production area, dences were visually assessed in the field and the identi- and this region makes up over one third of the total area ties of the pathogens were confirmed by laboratory test- allotted to potato nationally. -

Survey on Farmers Husbandry Practice for Dairy Cows in Alefa and Quara Districts of North Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia

SMGr up Research Article International Survey on Farmers Husbandry Practice for Journal of Animal Dairy Cows in Alefa and Quara Districts Science of North Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia Bernabas Ayeneshet1*, Zewdu Wondifraw2 and Michael Abera2 1Department of Animal Production and Extension, University of Gondar, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Sciences, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia Article Information Abstract Received date: Nov 28, 2017 The aim of the study was to describe the dairy cow’s husbandry practice of farmers in Alefa and Quara Accepted date: Dec 08, 2017 districts of North Gondar Zone Amhara National Regional State Ethiopia. Three Kebeles from each district, a total of six Kebeles were selected through purposive sampling procedure. Finally, 376 households (208 Published date: Dec 12, 2017 households from Quara and 168 households from Alefa) who had at least one lactating cow were selected through systematic random sampling procedure. Data were collected by using structured questionnaire and *Corresponding author the collected data were analyzed by using statistical package for social science (SPSS Version 20). The main source of feed for Alefa district was, crop residue and private grazing land (36.7%), crop residue, communal and Bernabas Ayeneshet, Faculty of private grazing land (41.4%), while for Quara district, communal grazing land (49.8%) and private, communal Veterinary Medicine, Department of and crop residue (39.6%)were the main feed sources. In respective order, about 70.8 and 81.3% of respondents Animal Production, University of Gondar, for Alefa and Quara districts were confirmed that river water was the main source for dairy cows. -

A Phenotypic and Genetic Characterized Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in Ethiopia

International Journal of Genetics 4(1): 04-10, 2014 ISSN 2222-1301 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.ijg.2014.4.1.8523 A Phenotypic and Genetic Characterized Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in Ethiopia Addis Getu and Aschalew Tadesse Department of Animal Production and Extension, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Gondar, Ethiopia Abstract: Review was conducted in Ethiopia during the year of 2014 to identify phenotypic and genetic characterized indigenous chicken ecotypes in Ethiopia. The data stated that poultry is a name given to domesticated birds kept by humans for eggs, meat and feathers. Thus domesticated poultry species are originated from the genus Gallus domestics. In Ethiopia except chickens, the others are found in their natural habitat. Thus domesticated chickens ecotypes are characterized in both phenotypic and genetic methodologies. Based on phenotype about 17 indigenous chicken ecotypes are identified and characterized. Among phenotypic characterized chickens are Chefe, Jarso, Tilili, Horro, Tepi, Gelila, Debre-Elias, Melo-Hamusit, Gassay, Guangua, Mecha, Farta, Konso, Mandura, Sheka, Naked neck, Gugut and Gasgie. Whereas some of the phenotypic characterized chickens ecotypes are additionally identified their genetic variation using molecular characterization methods such as Debre- Elias, Melo- Hamusit, Tilili, Gassay and Naked Neck. Those indentified chicken ecotypes have their own unique morphological and genetic characteristics. Thus chicken ecotypes are providing important opportunities for increasing protein production and income generating for smallholders having short generation interval and high rate of productivity. Production system of those identified chicken were majorly traditional extensive type. Diseases, predators, lack of market facility, shortage of feed and poor extension service were the major barriers of production system of identified chickens. -

RFQ for Goods/Services

Section II: Schedule of Requirements / Terms of Reference (ToR) eSourcing reference: ITB/2019/11476 GENERAL DESCRIPTION Service description: Establishment of a Long Term Agreement (LTA) for the Provision of Vehicle Rental Services for all Regional States in Ethiopia except Somali Regional State; Ethiopia Location: All Regional States Zones and Woredas except Somali Regional State - Ethiopia Duration: Long Term Agreement (LTA) to be signed for two (2) years period with a possibility of extension for one more year based on satisfactory performance I. BACKGROUND The United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) is a self-financing organization within the United Nations Family and operates within over sixty (60) countries. It is mandated to serve people in need by expanding the ability of the United Nations, governments and other partners to manage Projects, Infrastructure and Procurement in a sustainable and efficient manner. Within these three core areas of expertise, UNOPS provides its partners with advisory, implementation and transactional services, with projects ranging from building schools and hospitals to procuring goods and services and training local personnel. UNOPS works closely with governments and communities to ensure increased economic, social and environmental sustainability for the projects we support, with a focus on developing national capacity. UNOPS Ethiopia Operational Hub (ETOH) as part of achieving its mission was created covering the three Horn of Africa countries (Ethiopia, Sudan and Djibouti). UNOPS has supported the Government of Ethiopia, UN organizations and other development partners in the country since 2009. Based in Addis Ababa, our team offers a broad range of project management, procurement and infrastructure development, and advisory services, focusing on health, agriculture, social, humanitarian and economic sectors.