The Interlopers Exhibition Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Marks Land Marks

Land Marks Land Marks Mary Anne Barkhouse Wendy Coburn Brendan Fernandes Susan Gold Jérôme Havre Thames Art Gallery Art Gallery of Windsor Art Gallery of Peterborough Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Land marks : Mary Anne Barkhouse, Wendy Coburn, Brendan Fernandes, Susan Gold and Jérôme Harve. Catalogue for a traveling exhibition held at Thames Art Gallery, June 28 – August 11, 2013; Art Gallery of Windsor, April 20 – June 15, 2014; Art Gallery of Peterborough, January 16 – March 15, 2015. Curator: Andrea Fatona ; co-curator: Katherine Dennis ; essays: Katherine Dennis, Andrea Fatona, Caoimhe Morgan-Feir. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-894651-89-9 (pbk.) Contents 1. Identity (Psychology) in art — Exhibitions. 2. Human beings in art — Exhibitions. 3 3. Human ecology in art — Exhibitions. 4. Nature — Effect of human beings on — Exhibitions. Introduction 5. Landscapes in art — Exhibitions. 6. Art, Modern — 21st century — Exhibitions. I. Fatona, Andrea, 1963–, writer of added text II. Morgan-Feir, Caoimhe, writer of added text 7 III. Dennis, Katherine, 1986–, writer of added text IV. Art Gallery of Peterborough, host institution Essay by Andrea Fatona V. Art Gallery of Windsor. host institution VI. Thames Art Gallery, host institution, issuing body 19 N8217.I27L36 2013 704.9’49126 C2013-906537-7 Land Marks Essay by Katherine Dennis 41 Redrawing the Map Essay by Caoimhe Morgan-Feir 50 Artist Biographies 52 List of Works (previous; endsheet) Brendan Fernandes; Love Kill, 2009 (video still) Introduction We are pleased to present Land Marks, an exhibition that features five artists whose works draw our attention to the ways in which humans mark themselves, others, and their environments in order to establish identities, territory, and relationships to the world. -

Comparisons of Laterality Between Wolves and Domesticated Dogs (Canis Lupus Familiaris)

Comparisons of laterality between wolves and domesticated dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) By Lindsey Drew Submitted to the Board of Biology School of Natural Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Purchase College State University of New York May 2015 ______________________________ Sponsor: Dr. Lee Ehrman _______________________________ Co-Sponsor: Rebecca Bose of the Wolf Conservation Center Table of Contents Abstract Page 2 Introduction Pages 3-18 Materials and Methods Pages 18-25 Results Pages 25-28 Discussion Pages 29-30 1 Abstract I compared laterality in Canis lupus familiaris (domesticated dog) with: Canis lupus occidentalis (Canadian Rocky Mountain wolves), Canis rufus (red wolves), Canis lupus baileyi (Mexican wolves), and Canis lupus arctos (Artic wolf), all related. Each wolf species was grouped into a single category and was compared to domesticated dogs. The methods performed on domesticated dogs were the KongTM test and the step test. For wolves the PVC test was created to simulate the KongTM test and a step test for comparison. My hypothesis was that Canis lupus familiaris and Canis lupus will show consistent lateralized preferences between both species. The significance of this study is that laterality in Canis lupus familiaris has been studied multiple times with varying results. The purpose is to determine the possibility of laterality in Canis lupus familiaris being a conserved trait. This study has the potential to give greater meaning to laterality and the benefits of right or left sidedness or handedness. The total amount of paw touches recorded under each category, for the step test in dogs were 280 (50.5%) left and 274 (49.5%) right, for the KongTM test there were 278 left (50.3%) and 275 right (49.7%). -

Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics

Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics By Jonathan G. Way Published by Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research - www.EasternCoyoteResearch.com E-book • Citation: • Way, J.G. 2021. E-book. Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics. Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research, Barnstable, Massachusetts. 277 pages. Open Access URL: http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/CoywolfBook. • Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan G. Way, Ph.D., Founder of Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research. • Photography by Jonathan Way unless noted otherwise. • All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, e-mailing, or by any information storage, retrieval, or sharing system, without permission in writing or email to the publisher (Jonathan Way, Eastern Coyote Research). • To order a copy of my books, pictures, and to donate to my research please visit: • http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/store or MyYellowstoneExperience.org • Previous books by Jonathan Way: • Way, J. G. 2007 (2014, revised edition). Suburban Howls: Tracking the Eastern Coyote in Urban Massachusetts. Dog Ear Publishing, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. 340 pages. • Way, J. G. 2013. My Yellowstone Experience: A Photographic and Informative Journey to a Week in the Great Park. Eastern Coyote Research, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. 152 pages. URL: http://www.myyellowstoneexperience.org/bookproject/ • Way, J. G. 2020. E-book (Revised, 2021). Northeastern U.S. National Parks: What Is and What Could Be. Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research, Barnstable, Massachusetts. 312 pages. Open Access URL: http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/NortheasternUSNationalParks/ • Way, J.G. 2020. E-book (Revised, 2021). The Trip of a Lifetime: A Pictorial Diary of My Journey Out West. -

DAVEANDJENN Whenever It Hurts

DAVEANDJENN Whenever It Hurts January 19 - February 23, 2019 Opening: Saturday January 19, 3 - 6 pm artists in attendance detail: “Play Bow” In association with TrépanierBaer Gallery, photos by: M.N. Hutchinson GENERAL HARDWARE CONTEMPORARY 1520 Queen Street West, Toronto, M6R 1A4 www.generalhardware.ca Hours: Wed. - Sat., 12 - 6 pm email: [email protected] 416-821-3060 DaveandJenn (David Foy and Jennifer Saleik) have collaborated since 2004. Foy was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1982; Saleik in Velbert, Germany, in 1983. They graduated with distinction from the Alberta College of Art + Design in 2006, making their first appearance as DaveandJenn in the graduating exhibition. Experimenting with form and materials is an important aspect of their work, which includes painting, sculpture, installation, animation and digital video. Over the years they have developed a method of painting dense, rich worlds in between multiple layers of resin, slowly building up their final image in a manner that is reminiscent of celluloid animation, collage and Victorian shadow boxes. DaveandJenn are two times RBC Canadian Painting Competition finalists (2006, 2009), awarded the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta’s Biennial Emerging Artist Award (2010) and longlisted for the Sobey Art Award (2011). DaveandJenn’s work was included in the acclaimed “Oh Canada” exhibition curated by Denise Markonish at MASS MoCA – the largest survey of contemporary Canadian art ever produced outside of Canada. Their work can be found in both private and public collections throughout North America, including the Royal Bank of Canada, the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, the Calgary Municipal Collection and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. -

Palynology of Badger Coprolites from Central Spain

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 226 (2005) 259–271 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Palynology of badger coprolites from central Spain J.S. Carrio´n a,*, G. Gil b, E. Rodrı´guez a, N. Fuentes a, M. Garcı´a-Anto´n b, A. Arribas c aDepartamento de Biologı´a Vegetal (Bota´nica), Facultad de Biologı´a, 30100 Campus de Espinardo, Murcia, Spain bDepartamento de Biologı´a (Bota´nica), Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Auto´noma de Madrid, 28049 Cantoblanco, Madrid, Spain cMuseo Geominero, Instituto Geolo´gico y Minero de Espan˜a, Rı´os Rosas 23, 28003 Madrid, Spain Received 21 January 2005; received in revised form 14 May 2005; accepted 23 May 2005 Abstract This paper presents pollen analysis of badger coprolites from Cueva de los Torrejones, central Spain. Eleven of fourteen coprolite specimens showed good pollen preservation, acceptable pollen concentration, and diversity of both arboreal and herbaceous taxa, together with a number of non-pollen palynomorph types, especially fungal spores. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the coprolite collection derives from badger colonies that established setts and latrines inside the cavern over the last three centuries. The coprolite pollen record depicts a mosaic, anthropogenic landscape very similar to the present-day, comprising pine forests, Quercus-dominated formations, woodland patches with Juniperus thurifera, and a Cistaceae- dominated understorey with heliophytes and nitrophilous assemblages. Although influential, dietary behavior of the badgers does not preclude palaeoenvironmental -

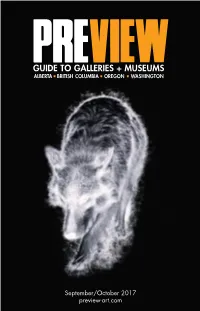

September/October 2017 Preview-Art.Com

September/October 2017 preview-art.com Installation Storage Shipping Transport Framing Providing expert handling of your fine art for over thirty years. 155 West 7th Avenue, Vancouver, BC Canada V5Y 1L8 604 876 3303 denbighfas.com [email protected] Installation Storage Shipping Transport Framing Providing expert handling of your fine art for over thirty years. 155 West 7th Avenue, Vancouver, BC Canada V5Y 1L8 604 876 3303 denbighfas.com [email protected] BRITISH COLUMBIA ALBERTA Laxgalts’ap Prince Rupert Prince George St. Albert Skidegate Edmonton HAIDA GWAII North Vancouver Deep Cove West Vancouver Port Moody Williams Lake Vancouver Coquitlam Burnaby Maple Ridge Richmond New Westminster Chilliwack Banff Calgary Surrey Fort Langley Salmon Arm Tsawwassen White Rock Abbotsford Kamloops Black Diamond Vernon Campbell River Courtenay Whistler Kelowna Medicine Hat Cumberland Roberts Creek Penticton Nelson Qualicum Beach Vancouver Lethbridge Port Alberni (see map above) Grand Forks Castlegar Nanaimo Salt Spring Is. Bellingham Victoria La Conner Friday Harbor Everett Port Angeles Spokane Bellevue Bainbridge Is. Seattle Tacoma WASHINGTON Pacific Ocean Astoria Cannon Beach Portland Salem OREGON 6 PREVIEW n SEP-OCT 2017 H OPEN LATE ON FIRST THURSDAYS September/October 2017 Vol. 31 No.4 ALBERTA PREVIEWS & FEATURES 8 Banff, Black Diamond, Calgary 10 Yechel Gagnon: Midwinter Thaw 13 Edmonton Newzones 14 Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, St. Albert 12 Citizens of Craft Alberta Craft Gallery, Calgary BRITISH COLUMBIA 15 Cutline: From the Archives of the Globe -

ROSALIE FAVELL | Www

ROSALIE FAVELL www.rosaliefavell.com | www.wrappedinculture.ca EDUCATION PhD (ABD) Cultural Mediations, Institute for Comparative Studies in Art, Literature and Culture, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (2005 to 2009) Master of Fine Arts, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States (1998) Bachelor of Applied Arts in Photographic Arts, Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1984) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Rosalie Favell: Shifting Focus, Latcham Art Centre, Stoufville, Ontario, Canada. (October 20 – December 8) 2018 Facing the Camera, Station Art Centre, Whitby, Ontario, Canada. (June 2 – July 8) 2017 Wish You Were Here, Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, M’Chigeeng, Ontario, Canada. (May 25 – August 7) 2016 from an early age revisited (1994, 2016), Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Regina, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. (July – September) 2015 Rosalie Favell: (Re)Facing the Camera, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. (August 29 – November 22) 2014 Rosalie Favell: Relations, All My Relations, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. (December 12 – February 20, 2015) 2013 Muse as Memory: the Art of Rosalie Favell, Gallery of the College of Staten Island, New York City, New York, United States. (November 14 – December 19) 2013 Facing the Camera: Santa Fe Suite, Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States. (May 25 – July 31) 2013 Rosalie Favell, Cube Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (April 2 – May 5) 2013 Wish You Were Here, Art Gallery of Algoma, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. (February 28 – May 26) 2012 Rosalie Favell Karsh Award Exhibition, Karsh Masson Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (September 7 – October 28) 2011 Rosalie Favell: Living Evidence, Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. -

Dancing Skeleton Marionette Assembly Instructions

DANCING SKELETON MARIONETTEASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS- WHAT YOU'LL NEED: A needle, thread, scissors, Elmer's glue (or glue sticks) and a straight-edge (ruler). HELPFUL HINTS: You can make an extra-fancy version of this puppet by gluing parts pages two and three to black construction paper before cutting out the parts. This will make the insides of the parts, where visible, black to match the outsides. As with most of the toys, this puppet should be printed on heavy card stock. Start by cutting out the general area of the piece you're working on, so you won't have extra paper flopping around. Then carefully cut out the object itself (being careful not to cut off any of the tabs). Once the item is cut out, you'll want to fold everyplace that needs folding before taping or gluing anything. The fast easy way to make folds is to fold the paper over the edge of a ruler or other straight-edge. Once the shape is folded properly you may then tape or glue everything in place. DANCING SKELETON MARIONETTE ASSEMBLY: Begin by cutting out the body piece on Page 1. Fold down the blue panel, and then fold down along all seven blue lines. Glue the blue panel to the back of the front panel, forming a rectangular box. Glue the end tab with the bones over the printed bones on the back panel, closing the bottom of the box. Next fold the blank black tab over the back panel and glue it down, closing the top of the box. -

MA CV Oct 2019

MARY ANNE BARKHOUSE AOCA, RCA Born: Vancouver, British Columbia 1961 SELECTED EXHIBITIONS Ontario College of Art, Honours Graduate 1991 2011 2019 Close Encounters: the Next 500 Years Undomesticated Plug-In ICA, Winnipeg, MB Kofflery Centre for the Arts maison de loup (solo) How to Breathe Forever Visual Arts Centre of Clarington, Bowmanville, ON Onsite Gallery, Toronto, ON what the fox saw 2018 Lafreniere and Pai Gallery, Ottawa, ON The Interlopers (solo) 2010 McLaren Art Centre, Barrie, ON It Is What It Is National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON Le Rêve aux Loups (solo) Foreman Art Gallery, Sherbrooke, QC Strange Nature Richmond Art Gallery, Richmond, BC 2017 Le Rêve aux Loups (solo) Reins of Chaos II (solo) Latcham Gallery, Stouffville, ON Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto, ON Esker Foundation, Calgary, AB Game (solo) Urban Shaman, Winnipeg, MB Beneath the Tame (2-person show with Anna Williams) House Beautiful McDonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph, ON Gallery 101, Ottawa, ON 2009 Oh Ceramics! (group exhibition) The Muhheakantuck in Focus The Esplanade Art Gallery Medicine Hat, AB Wave Hill Cultural Centre, Bronx, NY Resilience, National Billboard Exhibition Project Home/Land Security Lee-Ann Martin, Shawn Dempsey, MAWA University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON 2016 2008 Culture Shift The Reins of Chaos (solo) Art Mur, Montreal, QC Ottawa Art Gallery, Ottawa, ON 2015 Beaver Tales: Canadian Art and Design Human Nature University of Toronto Art Centre, Toronto, ON Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, ON 2013 2007 Sakahàn Boreal Baroque (solo - national touring until 2009) National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, ON Regency (solo) Terra Incognita Rodman Hall, St. -

The Mediterranean Palynological Societies Symposium 2019

The Mediterranean Palynological Societies Symposium 2019. Abstract book. Stéphanie Desprat, Anne-Laure Daniau, Maria Fernanda Sánchez Goñi To cite this version: Stéphanie Desprat, Anne-Laure Daniau, Maria Fernanda Sánchez Goñi. The Mediterranean Palyno- logical Societies Symposium 2019. Abstract book.. MedPalyno 2019, Jul 2019, Bordeaux, France. Université de Bordeaux, pp.142, 2019, 978-2-9562881-3-8. hal-02274992 HAL Id: hal-02274992 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02274992 Submitted on 30 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ABSTRACT BOOK The Mediterranean Palynological Societies Symposium 2019 The joint symposium of the APLF, APLE and GPP-SBI Bordeaux, July 9-10-11, 2019 Title: The Mediterranean Palynological Societies Symposium 2019. Abstract book. Editors: St´ephanie Desprat, Anne-Laure Daniau and Mar´ıa Fernanda S´anchez Go˜ni Publisher: Université de Bordeaux IBSN: 978-2-9562881-3-8 E-book available on https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/ ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Local committee from the EPOC research unit (UMR 5805: CNRS, Universite´ de Bordeaux, EPHE) Charlotte Clement´ Anne-Laure Daniau Stephanie´ Desprat Ludovic Devaux Tiffanie Fourcade Marion Genet Muriel Georget Laurent Londeix Maria F. Sanchez Goni˜ Coralie Zorzi Enlarged committee - Presidents of the APLF, GPPSBI and APLE Vincent Lebreton, HNHP, UMR 7194 CNRS-Mus´eumNational d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN)-UPVD (France) Anna Maria Mercuri, Universit`adegli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Department of Life Sciences (Italy) Pilar S. -

From Voutube to Touh.Ill, Pentatoriix Music Amazes JENNIFER EMILY ADDY LAI STAFF WRITER STAFF WRITER

VOL.48 ISSUE 1448 OCT 6, 2014 From VouTube to Touh.ill, Pentatoriix music amazes JENNIFER EMILY ADDY LAI STAFF WRITER STAFF WRITER YouTube sensation and acapella group, Pentatonix, perform at Touhill Performing Arts Center PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF ADDY LAIITHE CURRENT as well as the winning group of show was the group's cover the third season of NBC's "The of "Say Something," origi- Sing-Off,': . An American acap nally performed by A Great Big pella group that consists of five World feat. Christina Aguilera. vocalists who originated from The vocalists' voices echoed Arlington, Texas. Pentatonix throughout the theater and sent is comprised of lead vocalists chills through the captivated Scott Hoying; Kristin "Kristie" crowd. Their performance of the Maldonado, and Mitch GrasSi, "Evolution of Music" demon vocal bass Avriel ''Avi'' Kaplan, strated their technical skills, and and beat boxer Kevin K.O. Olu accomodated their audience of sola. Originally a three member different ages. group comprised of Scott, Kris Pentatonix's involvment tie, and Mitch, they eventually with their audience, a con found the need for a bassist and nection that is rarely seen at a beatboxer to reach stardom. concerts, was definitely one of The band name derives from the the key reasons why audiences five-note music scale, pentaton . were begging for an encore. ic, replacing the 'c' with an 'x'. Mitch, wanting a photograph The band redefines the meaning. of the enthusiastic crowd, took of an acapella concert. out his cell phone and started to Pentatonix performed take a panoramic photo as Scott some songs froln their previ hummed to the tune of "Jeop ous albums along with a couple ardy". -

Oshawa Oshawa Sculptures Septoct Artscene

Volume 26 – Issue 5 September, October, 2021 Circulation – On-Line Only Connect Garland Gate To The Future The Compass • Edward Falkenberg ~ 2004 Durham College/Ontario Tech U. Gordon Willey Building / Bus Loop Stainless Steel Ring Dimensions: 4.88m H/W x .46m D • Douglas Bentham ~ 2006 • André Fournelle ~ 2013 • Darlene Bolahood ~ 2005 Connect is a powerful sculpture de- Durham College/Ontario Tech U. Durham College/Ontario Tech U. Durham College/Ontario Tech U. signed by Claremont sculptor Ed- Avenue of Champions Avenue of Champions Gordon Willey Building / Bus Loop ward Falkenberg. It represents the Painted Steel Corten Steel, Gold Leaf Steel, Polycarbonate Sheets many disciplines being studied. It Representing Saskatchewan, Representing Quebec Dimension: 12m H symbolizes the connection between Dimensions: 5.2m H x 2.7m W x 2.4m D Dimensions: 8m H x 5m W x 130cm D Former faculty member Darlene Bo- business, industry, government, Douglas Bentham is known interna- “For “Gate to the Future” I lahood’s idea was to build the four technology, education and the col- tionally as a constructivist sculptor, towers to align to true north so that lege and university, as well as the however he originally graduated was inspired by the music whenever the sun reached the tower many partnerships the shared cam- from the University of Saskatchewan and sound records sent at 12 o’clock, the blue panel would pus has established with the commu- with a fine arts degree in painting. point to solar noon. She saw her nity. Its segments are joined together When talking about Garland he into space in 1977 by piece representing time, direction, to form a whole, the whole being said NASA on the Voyager and the freedom of choice.