From Ozzie and Harriet to Raymond and Debra: an Analysis of the Changing Portrayals of American Sitcom Parents from the 1950’S to the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

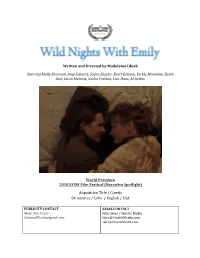

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

The Evolving Perception of Controversial Movies

ARTICLE Received 6 Jul 2015 | Accepted 2 Nov 2015 | Published 8 Dec 2015 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2015.38 OPEN The evolving perception of controversial movies Luca Amendola1, Valerio Marra2 and Miguel Quartin3 ABSTRACT Polarization of opinion is an important feature of public debate on political, social and cultural topics. The availability of large internet databases of users’ ratings has permitted quantitative analysis of polarization trends—for instance, previous studies have included analyses of controversial topics on Wikipedia, as well as the relationship between online reviews and a product’s perceived quality. Here, we study the dynamics of polarization in the movie ratings collected by the Internet Movie database (IMDb) website in relation to films produced over the period 1915–2015. We define two statistical indexes, dubbed hard and soft controversiality, which quantify polarized and uniform rating distributions, respec- tively. We find that controversy decreases with popularity and that hard controversy is relatively rare. Our findings also suggest that more recent movies are more controversial than older ones and we detect a trend of “convergence to the mainstream” with a time scale of roughly 40–50 years. This phenomenon appears qualitatively different from trends observed in both online reviews of commercial products and in political debate, and we speculate that it may be connected with the absence of long-lived “echo chambers” in the cultural domain. This hypothesis can and should be tested by extending our analysis to other forms -

Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 Looking Forward to High School and College Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools Elaine M. Allensworth, Julia A. Gwynne, Paul Moore, and Marisa de la Torre TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary Chapter 5 55 Who Is at Risk of Earning Less 7 Introduction Than As or Bs in High School? Chapter 1 Chapter 6 17 Issues in Developing and Indicators of Whether Students Evaluating Indicators 63 Will Meet Test Benchmarks Chapter 2 Chapter 7 23 Changes in Academic Performance Who Is at Risk of Not Reaching from Eighth to Ninth Grade 75 the PLAN and ACT Benchmarks? Chapter 3 Chapter 8 29 Middle Grade Indicators of How Grades, Attendance, and High School Course Performance 81 Test Scores Change Chapter 4 Chapter 9 47 Who Is at Risk of Being Off-Track Interpretive Summary at the End of Ninth Grade? 93 99 References 104 Appendices A-E ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work. We thank Robert Balfanz and Julian Betts for providing us with very thoughtful review and feedback which were used to revise this report. We also thank Mary Ann Pitcher and Sarah Duncan, at the Network for College Success, and members of our Steering Committee, especially Karen Lewis, for their valuable feedback. Our colleagues at UChicago CCSR and UChicago UEI, including Shayne Evans, David Johnson, Thomas Kelley-Kemple, and Jenny Nagaoka, were instrumental in helping us think about the ways in which this research would be most useful to practitioners and policy makers. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development's Next Wave Intro

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development’s Next Wave Intro In spring of 2015, LISC NYC’s Executive Director, Sam Marks invited friends of LISC - top economists, policy analysts, journalists, community development gurus and current leaders of some of the city’s top community development corporations - to join staff in strategizing around critical questions facing New York’s community development sector. What can LISC NYC and its community development partners do to counter global and national trends exacerbating economic polarization? What is community development’s role in shaping the city’s upcoming neighborhood rezonings, preserving affordable housing, and, building human capital? How can the industry scale up even as it consolidates and redeploys resources to new areas and programming? Over the course of three panel discussions moderated by Marks, presenters and LISC NYC staff shed some light on next wave strategies for New York City’s neighborhoods. Panel 1: Global City/Global Trends: Panelists explained the global trends driving high real estate prices, economic polarization, gentrification and displacement and debated about the levers available to city government, LISC NYC and community developers to alleviate the harsh impacts on low and moderate income New Yorkers. Jonathan Bowles, Executive Director, Center for an Urban Future . Adam Davidson, co-founder and co-host, Planet Money . Ingrid Gould Ellen, Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Director of the Urban Planning Program, New York University Wagner; Faculty Director, Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy . Chris Herbert, Managing Director, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies Panel 2: Community development past, present and future: Former LISC NYC directors distilled their experiences using real estate strategies to address neighborhood issues and considered strategies to meet current challenges. -

Many Loves Ofdobie Gillis, Hawaiian Eye, 77 Sunset Strip, Wagon Train, Ben Casey, My Mother the Car, and Perry Mason

BARBARA BAIN Born in Chicago on September 13th, Barbara Bain graduated from the University of Illinois with a Bachelor’s Degree in Sociology before relocating to New York City. Once there, Bain found gainful employment as a high fashion model and explored her life-long love of dance by studying with Martha Graham, master of American modern dance. Further exploring her interest in the arts, Bain began her acting training in the private class of the most famous and respected of all acting teachers, Lee Strasberg. After a successful audition, she accepted an invitation to become a member of his legendary The Actors Studio. Bain toured with the road company of Paddy Chayefsky's Middle of the Night, a tour which landed her in Los Angeles, and not long thereafter Bain found work on some of the most popular television shows of the day. She appeared opposite Larry Hagman in United Artists' Harbormaster and with Darrin McGavin in the popular Mike Hammer series. Perhaps her first real big break came, however, when she was cast in the recurring role of Karen Wells, love interest of David Janssen, in the seminal private-eye series, Richard Diamond, Private Detective. Bain continued to work steadily, appearing in numerous television series: Tightrope, The Law and Mr. Jones, Straightaway and Adventures in Paradise. She also had the opportunity to flex her comedy skills in one of the most memorable episodes of the classic The Dick Van Dyke Show, created by Carl Reiner. In the episode "Will You Two Be My Wife," Bain turned in a hilarious performance as "Dorie-doo," a blonde bombshell with whom Van Dyke must break-up in order to marry the ever-perky Mary Tyler Moore. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Mbmbam 391: Jeff Wolfworthy Published on January 29, 2018 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family

MBMBaM 391: Jeff Wolfworthy Published on January 29, 2018 Listen here on TheMcElroy.family Intro (Bob Ball): The McElroy brothers are not experts, and their advice should never be followed. Travis insists he’s a sexpert, but if there’s a degree on his wall, I haven’t seen it. Also, this show isn’t for kids, which I mention only so the babies out there will know how cool they are for listening. What’s up, you cool baby? [theme music, “(It’s a) Departure” by The Long Winters, plays] Justin: Hello, everybody, and welcome to My Brother, My Brother and Me, an advice show for the modern era. I’m your oldest brother, Justin McElroy! Travis: I’m your middlest brother, Travis McElroy! Griffin: I’m your sweet baby brother and 30 Under 30 media luminary, Griffin McElroy. Justin: Are you ready for more footballll? Griffin: I’m ready for twice the amount of football I currently consume, which would still... Justin: An undetermined night of the week party! Griffin: Whew! [sing-song] It’s all night, and the balls are hot; don’t touch the balls, ‘cause you’ll burn your hands! Justin: [sing-song] We have a bunch—some announcers to be determined that are gonna get it kickstarted. Travis: [sing-song] Or maybe, like, hand-off start it. We don’t know, we haven’t finished out the rules yet. Griffin: [sing-song] There may not even be a ball this time. It’s football of the mind, XFL. Justin: You’ve probably guessed we’re.. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Community Rebranding: a Case Study

COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Hospitality Management By Michelle L. Pecheck Spring 2015 SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY AUTHOR: Michelle L. Pecheck DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2015 The Collins College of Hospitality Management Dr. Ed Merritt _________________________________________ Project Committee Chair Associate Professor Dr. Margie Jones _________________________________________ Associate Professor Dr. Neha Singh _________________________________________ Director of Graduate Studies Associate Professor ii ABSTRACT Intro: This case study profiles Claremont, a city of approximately 37,000 residents. Since its formation in 1887, it has primarily been known as a college town with a history of citrus production. This case study investigates what components would need to be in place to rebrand or reposition the city as a unique, healthful destination. Case: A resident survey, interviews, and focus groups were used to gather qualitative data about residents’ perceptions of the city’s current brand and potential rebranding. Management & Outcome: Scope of work for the focus city included data gathering from residents, and identification of projects, services, and designations to support marketing of the city as a health/wellness destination. Discussion: Data from surveys, focus groups, and key informant interviews indicated that residents were uncertain of the City’s current brand, in general appeared to care little about the brand, and lacked information about the City’s interest in a possible future rebranding. Further, City documents revealed a history of departmental rebrandings that may have obscured the City’s current brand image.