Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forty-Second Day (Legislative Day of March 11) Morning Session

FORTY-SECOND DAY (LEGISLATIVE DAY OF MARCH 11) MORNING SESSION. Mr. HALFHILL: After Mr. Weybrecht has fin- ished. THURSDAY} March 21, 1912. The PRESIDENT: We have been following, not The Convention met pursuant to recess, was called always consistently, the names on the list, but the presi to order by the president and opened with prayer by dent states that he would recognize the member from the Rev. F. B. Bishop of Columbus, Ohio. Allen [Mr. HALFHILL] next if there were no objection. The PRESIDENT: Gentlemen of the Convention: The question before the house is the Crosser resolution The president would ask the indulgence of the Conven with the three pending amendments. tion to make a very brief statement in reference to the Mr. PETTIT: I rise to a question of personal priv unfortunate episode of last evening. ilege. The president is aware that the proper form of stat The PRESIDENT: Does the gentleman from Stark ing the result of a vote on a question to recess is "The [Mr. WEYBRECHT] yield? motion seems to prevail, the motion prevails", because 1\1r. WEYBRECHT: No,_ sir; I will not. in that form a demand for a division may be made be Mr. PETTIT: But I rise to a question of personal fore the vote is finally announced. On the theory that privilege. after the vote is finally announced the Convention is re 1fr. WEYBRECHT: I would prefer not to yield. cessed and no further business in order, the president Mr. PETTIT: I want to know- did carelessly neglect to state the matter in that formal Mr. -

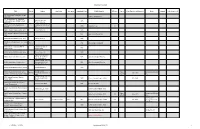

Cesarean Section Rates from the 2015 Leapfrog Hospital Survey

Cesarean Section Rates from the 2015 Leapfrog Hospital Survey Results reflect submissions received by December 31, 2015 Hospital City State Rate Performance Alaska Regional Hospital Anchorage AK 33.5% Willing to Report Bartlett Regional Hospital Juneau AK Declined to Respond Central Peninsula General Hospital Soldotna AK Declined to Respond Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Fairbanks AK 15.3% Fully Meets Standard Mat‐Su Regional Medical Center Palmer AK Declined to Respond Providence Alaska Medical Center Anchorage AK 20.0% Fully Meets Standard Andalusia Regional Hospital Andalusia AL 22.1% Fully Meets Standard Athens‐Limestone Hospital Athens AL Declined to Respond Atmore Community Hospital Atmore AL Declined to Respond Baptist Medical Center East Montgomery AL Declined to Respond Baptist Medical Center South Montgomery AL Declined to Respond Bibb Medical Center Centreville AL Declined to Respond Brookwood Medical Center Birmingham AL 31.9% Some Progress Bryan W. Whitfield Memorial Hospital Demopolis AL Declined to Respond Bullock County Hospital Union Springs AL Declined to Respond Cherokee Medical Center Centre AL Declined to Respond Citizens Baptist Medical Center Talladega AL Declined to Respond Clay County Hospital Ashland AL Declined to Respond Community Hospital of Tallassee Tallassee AL Declined to Respond Coosa Valley Medical Center Sylacauga AL Declined to Respond Crenshaw Community Hospital Luverne AL Declined to Respond Crestwood Medical Center Huntsville AL Declined to Respond Cullman Regional Medical Center Cullman AL Declined -

The Color Line in Ohio Public Schools, 1829-1890

THE COLOR LINE IN OHIO PUBLIC SCHOOLS, 1829-1890 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By LEONARD ERNEST ERICKSON, B. A., M. A, ****** The Ohio State University I359 Approved Adviser College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is not the work of the author alone, of course, but represents the contributions of many persons. While it is impossible perhaps to mention every one who has helped, certain officials and other persons are especially prominent in my memory for their encouragement and assistance during the course of my research. I would like to express my appreciation for the aid I have received from the clerks of the school boards at Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Warren, and from the Superintendent of Schools at Athens. In a similar manner I am indebted for the courtesies extended to me by the librarians at the Western Reserve Historical Society, the Ohio State Library, the Ohio Supreme Court Library, Wilberforce University, and Drake University. I am especially grateful to certain librarians for the patience and literally hours of service, even beyond the high level customary in that profession. They are Mr. Russell Dozer of the Ohio State University; Mrs. Alice P. Hook of the Historical and Philosophical Society; and Mrs. Elizabeth R. Martin, Miss Prances Goudy, Mrs, Marion Bates, and Mr. George Kirk of the Ohio Historical Society. ii Ill Much of the time for the research Involved In this study was made possible by a very generous fellowship granted for the year 1956 -1 9 5 7, for which I am Indebted to the Graduate School of the Ohio State University. -

The Miami Slaughterhouse

The Miami Slaughterhouse In the 1780’s, a Squirrel could reach Cincinnati from Pittsburg and never touch the ground. In part because of this heavy tree canopy, the land between the Little Miami River and the Great Miami River was known to have some of the richest farm land ever seen. The land between the Miami’s was a special hunting ground for the Indians. They would not give it up without a fight. In 1966, while researching a high school term paper, I found a diary written by Mary Covalt called “Reminiscences of Early Days about the construction and defense of Covalt Station primarily set during the years 1789 until 1795. “ My story tonight is about ordinary men and women coming down the Ohio River to settle in the land between the Little Miami and Great Miami Rivers. The Covalts who came down the Ohio and built Covalt Station in the area now known as Terrace Park were my ancestors. Mary Covalt’s diary along with other letters and personal accounts gives us the chance to use a zoom lens to focus on how life was lived was during this period. This story takes place in the Old Northwest Territory, and more specifically in the Ohio Territory and very specifically in the land between the two Miami Rivers. Not many of us would want to personally experience the sacrifices made to develop this land. Innocently, these pioneers came to a place that would embroil them in a life and death struggle for the next five years. These five years in the Old Northwest Territory would settle once and for all if America’s future growth would be west of the Allegany Mountains. -

A Glance at the Garden of Eden by the Editors

A Glance at the Garden of Eden by the Editors The river; the miles of distant hills extending along the Kentucky side of the stream; the less remote high lands of Ohio, rolling away in multitu- dinous waves of improved lands; the suburbs of the city to the north and east, and the city at the foot of the hill, teeming with its busy thousands, make up a prospect so rare that it may be said the park, for location, hardly has its peer. The avenues meander by graceful curves through the grounds, at every turn shutting out something the visitor has just seen, but revealing another landscape filled with new beauties. t hardly seems credible that Eden Park, described so glowingly in 1870, the I year of its dedication, could just twenty-four years earlier have been dis- missed as "broken hill land too poor to raise sauer kraut upon." Yet this was the rebuff which Nicholas Longworth met in 1846 when he proposed that the city buy a portion of his lands atop Mount Adams. Longworth had in fact tried for years—as early as 1818—to interest the city fathers in acquiring some of his land for park use, without success. In 1842 he offered suitable acreage at $500 an acre, which he claimed was well below its actual value, but his proposal was declined. The price, he was advised, was too high. With the refusal in 1846 of his latest offer, Longworth grew exasperated. The following year he published an article renewing his earlier offers and "remarking that he knew they would all be refused, but that he wished to stand on record as having offered to the city ground which would be in time worth five, ten, and twenty times its value then." Stung by the implication that his motive lay more with profit than with public service, Longworth de- clared that one day the people would be asking why sites on the hills had not been purchased earlier when land prices were low. -

Anthony Wayne M Em 0 R· I a L

\ I ·I ANTHONY WAYNE M EM 0 R· I A L 'I ' \ THE ANTHONY WAYNE MEMORIAL PARKWAY PROJECT . in OHIO -1 ,,,, J Compiled al tlze Request of the ANTHONY WAYNE MEMO RIAL LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE by lhr O..H. IO STATE ARCHAEOLOGICAL and H ISTORICAL SOCIETY 0 00 60 4016655 2 I• Columbus, Ohio 1944 ' '.'-'TnN ~nd MONTGOMERY COt Jt-rt"-' =J1UC llBR.APV Acknowledgments . .. THE FOLLOWING ORGANIZATIONS ass isted lll the compilation of this booklet : The A nthony Wayne Memo ri al J oint L egislative Cammi ttee The Anthony \Vayne Memori al Associati on The! Toledo-Lucas County Planning Commiss ions The Ohio D epa1 rtment of Conservation and Natural Resources The Ohio Department of Highways \ [ 4 J \ Table of Contents I Anthony Wayne Portrait 1794_ ·---···-· ·--· _____ . ----------- ·----------------- -------------------. _____ Cover Anthony Wayne Portrait in the American Revolution ____________________________ F rrm I ispiece Ii I I The Joint Legislative Committee_______ --------····----------------------------------------------------- 7 i· '#" j The Artthony Wayne Memorial Association ___________________________________ .-------------------- 9 I· The Ohio Anthony Wayne Memorial Committee _____________________________________ ---------- 11 I I I Meetings of the Joint Legislative Committee·------·--------- -·---------------------------------- 13 I I "Mad Anthony" Wayne a'dd the Indian \Vars, 1790-179.'---------------------------------- 15 lI The Military Routes of Wa.yne, St. Clair, and Harmar, 1790-179-t- ___________ . _______ 27 I The Anthony Wayne Memorial -

Seventy-Third Day

SEVENTY-THIRD DAY AFTERNOON S~SSION. committee needs further amendment than that submitted by the committee on Arrangement and Phraseology. I WEDNESDAY, May 22, 1912. merely call the attention of the committee to it because The Convention met pursuant to adj ournment, was the last sentence in the amended Proposal No. 72, being called to order by the president and opened with prayer that part of Proposal No. 174 that has been drawn by the member from Knox, the Rev. 1\/[r. McClelland. from Proposal No. 72, "laws may be pa~sed regulating The journal of Thursday, May 9, was read and the sale and conveyance of other personal property," is approved. in effect an article wholly devoted to corporations, and Mr. TAGGART: Mr. President: Just a brief word if the ordinary rule of construction of a constitutional of explanation. In order to expedite business, it is or statutory provision should prevail that would be the desire of the committee on Schedule that a certain construed in pari materia-if the member from High proposal be introduced in order that it may be engrossed land [1\/[r. BROWN] will excUse the latin expression-and and printed and be referred back to the committee. it would probably be held that this provision only applies While it is not in form, we desire to have it printed to to the sale and conveyance of personal property belong get the matter in shape. ing to corporations. If that sentence is amended that By unanimous consent the following proposal was laws may be passed regulating the sale and conveyance introduced and read the first time: of other personal property, whether owned by a corpora Proposal No. -

A. Lee Hannah

A. Lee Hannah Contact Wright State University Email: [email protected] Information School of Public and International Affairs Office: (937) 775-2904 317 Millett Hall Fax: (937) 775-2820 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy Web: www.aleehannah.com Dayton, OH 45434 Academic Wright State University, Dayton, OH Appointments Associate Professor of Political Science, 2019-present Assistant Professor of Political Science, 2015-2019 Education The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA Ph.D. Political Science, 2015 M.A. Political Science, 2011 Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA M.Ed. Curriculum and Instruction, 2004 B.A. History, 2003 Book Hannah, A. Lee and Daniel J. Mallinson. Green Rush: The Rise of Legal Marijuana in the American States. Under contract with New York University Press. Refereed [9] Mallinson, Daniel J., A Lee Hannah, and Gideon Cunningham1. (2021). “The Conse- Journal quences of Fickle Federal Policy: Administrative Hurdles for State Cannabis Policies.” Accepted Articles for publication at State and Local Government Review. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X20984540 [8] Mallinson, Daniel J. and A. Lee Hannah. (2020). “Policy and Political Learning: The De- velopment of Medical Marijuana Policies in the States.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 50(3): 344-369. DOI:10.1093/publius/pjaa006/5819235 [7] Hannah, A. Lee and Danielle C. Rhubart. (2020).“Teacher Perceptions of State Standards and Climate Change Pedagogy: Opportunities and Barriers for Implementing Consensus-informed Instruction on Climate Change.” Climatic Change, 158: 377-392. DOI: 10.1007/s10584-019-02490-8 [6] Hannah, A. Lee. (2019). “Developing a Mixed-Methods Research Agenda on Medical Mar- ijuana Policy.” SAGE Research Methods. -

INTRODUCTION the BEGINNINGS Nothing Challenges the Historical

INTRODUCTION THE BEGINNINGS Nothing challenges the historical imagination more than trying to recapture the landscape of the past. To imagine Springdale without the sounds of the automobile, the smells of gasoline and rubber, the hardness of the cement, the glare of street lights and the bright signs of the shopping malls seems almost impossible. Yet there was a time when the modern urban community that is today's Springdale was little more than a lush forest full of abundant natural resources undisturbed by human settlement. Along with the low rush of the wind, common sounds would have been the chirping of quail, parakeet and the passenger pigeon, the honk of wild geese and turkey, and the grunt of boars rooting the earth for acorns underneath the sturdy stands of oak. The odor of the virgin soil and the mushiness of vegetation slowly decaying in the perpetual forest gloom naturally complimented the contours of the gentle and rolling land, broken occasionally by natural ravines and small creeks. Over time humans, first Native Americans and then Europeans, altered the terrain. Yet essentially the contour remains as it was when the Miami Indian felt the lilt of the land beneath his feet as he made his way across it in search of game. He trod a well- beaten path or trace. From time immemorial, long before the first white explorer intruded, Springdale's destiny was shaped by its location on a key transportation route. The end of the American Revolution signaled a period of discovery and prolonged movement and settlement of the wilderness that is now the United States. -

FCGS Research Library Inventory List

INVENTORY 4/25/06 Title Vol. # Author Condition Category Copyright Date Publishing Co. # Pages Cost Date Purchased/Obtained Notes Copy # Lib. Congress # 150 Years Milan Township & Village Ledger Publishing Co. 1809-1959 175 Southwestern PA. Marriages Robert & Marietta Performed by Rev. Abraham Boyd 1976 (Fowler) Closson 1802-1849 1767 Berks County Pennsylvania Compiled by Katharine F. 1989 Closson Press 33 Archives Dix 1820 Census of Gallia County, Ohio Pierce, Homer C. 1976 1820 Federal Population Census Ohio 1964 Ohio Library Foundation Index 1830 Census of Gallia County, Ohio Pierce, Homer C. 1976 1830 Federal Population Census Ohio Vol. I & 1964 Ohio Library Foundation Index Vol. 2 1840 Census - Lucas and Part of Compiled by Tom & 1983 Fulton County. Beverly Reed 1840 Census of Gallia County, Ohio Pierce, Homer C. 1976 Copied from Microfilm 1850 Census Columbiana Co, Ohio Roll No. M-432 #669 1973 Ohio Genealogical Society Bell, Carol Willsey Compiled & Indexed from 1850 Census Darke County, Ohio Microfilm Roll M-674 1978 Ohio Genealogical Society Shilt, R & Short, A. 1850 Census Marshall County, Illinois Richard, Bernise C. 1975 Licking County 1860 Census Licking County, Ohio - Value Unclaimed OGS door Part III Genealogical Society of June 2002 Granville Township & Granville Village $2.50 prize OGS Compiled & Indexed from 1870 Federal Census of Mercer Microfilm Roll M-593 1995 Mercer County Chapter, OGS Mar 1999 County, Ohio #1242 1875 Historical Atlas of Lancaster Lois Ann Zook Mast 1991 Everts & Stewart County, Pennsylvania 1880 Census Index for Huron County Indexed by E.S. Thorn Huron County Chapter, OGS Ohio 1880 Census Records Noble County, Value Unclaimed OGS door Noble County Chapter, OGS 255 June 2002 Ohio $28.00 prize Purchased in 1883 Pensioners: Updated Index of Michael Elliott New Spiral Bound Military 2012 Summit county Chapter, OGS 263 Mar 2013 Memory of Beverly Northwest Ohio Todd Reed 1890 Special Census of Union 1993 Fulton County Chapter, OGS Veterans, Fulton County, Ohio 1970 Robinson's Henry County, Ohio Robinson Directories, Inc. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

PAST PURSUITS: Genealogy and Local History News at the Akron-Summit County Public Library

PAST PURSUITS: Genealogy and Local History News at the Akron-Summit County Public Library A Publication of the Special Collections Division Volume 2 Number 4 End of Year Edition If you are reading this newsletter, there is little doubt that you have been shocked by the sudden passage of time while digesting manuscripts or scrolling through reels of microfilm. The Special Collections staff has recently taken that pause and realized that 2004 is nearly upon us. This is a time for reflection. This has been a year of many accomplishments and some disappointments. We liken our situation to genealogical and local history research. In 2003, we have solved many puzzles, written many chapters, and clearly answered questions…while, of course, creating more questions. Yet we still have a great deal of work that remains to be done. We look upon 2004 and the challenges (or “brick walls” for genealogists) it presents with enthusiasm and zeal. We remain focused on collections and database development, outreach, preparation for the move to the new Main Library in the fall, and MOST IMPORTANTLY, continuation of excellent reference service to genealogy and local history researchers. You see, we are driven by the same interest in history that makes time fly when you research, leaving your family to wonder if you are ever coming home! To keep updated on construction efforts, visit: http://ascpl.lib.oh.us/construction/main.html#Downtown Please don’t forget that you can visit us at 1040 E. Tallmadge Avenue during library construction! All genealogy and local history collections are available.