Herbert Ponting and the Terra Nova Expedition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbert Ponting and the First Documentary 1

Herbert Ponting And The First Documentary 1 Herbert Ponting And The First Documentary One evening in mid-winter of 1911, in the coldest, most isolated place on earth, some two dozen men of the British Expedition to the South Pole gathered for a slide show. They were hunkered down in a wooden building perched on the edge of Antarctica. For them winter ran from late April to late August. In these four months the sun disappeared entirely leaving them in increasing darkness, at the mercy of gales and blizzards. If you stepped outside in a blizzard, you could become disoriented within a few yards of the hut and no one would know you were lost or where to look for you. On this evening, they were enjoying themselves in the warmth of their well insulated hut. One of their number, who called himself a “camera artist,” was showing them some of the 500 slides he had brought with him to help occupy the long winter hours. The camera artist was Herbert Ponting, a well known professional photographer. In the language of his time he was classified as a “record photographer” rather than a “pictorialist.”i One who was interested in the actual world, and not in an invented one. The son of a successful English banker, Ponting had forsworn his father’s business at the age of eighteen to try his fortune in California. When fruit farming and gold mining failed him, he took up photography, turning in superb pictures of exotic people and places, which were displayed in the leading international magazines of the time. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

Issue 93 (June 2021, Vol.16, No.3)

The Japan Society Review 93 Book, Stage, Film, Arts and Events Review Issue 93 Volume 16 Number 3 (June 2021) The opening review of our June issue explores the Minae is a semi-autobiographical novel using fiction to fascinating life and career of Herbert Ponting, the negotiate issues of nationhood, language, and identity photographer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra between Japan and the US. The Decagon House Murders Nova expedition to the South Pole. Ponting’s travels in by Ayatsuji Yukito is a murder mystery story which follows Japan during the Meiji period are likely to be of particular the universal conventions of this classic genre, while interest to readers and resulted in several photographic bringing to it a distinctively Japanese approach. series and publications including his Japanese memoirs In This issue ends with a review of a publication on Lotus-Land Japan. Japanese wild food plants written by journalist Winifred Another captivating yet very different figure in Bird. From wild mountain and forest herbs to bamboo Japanese culture is the yamamba, the mountain witch, part and seaweed, from Kyushu to Hokkaido, this guide offers of a widely recognised “old woman in the woods” folklore. detailed information on identification, preparation and Reviewed in this issue is a new collective publication recipes to discover and taste this part of the Japanese examining the history and representations of this female natural world. character in terms of gender, art and literature among other topics. Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández Two reviews in this issue focus on literary works recently translated into English. An I-Novel by Mizumura Contents 1) Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Editor Pioneer Filmmake by Anne Strathie Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández 2) Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch Reviewers edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. -

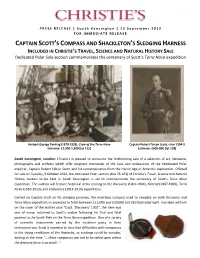

Captain Scott's Compass and Shackleton's Sledging

PRESS RELEASE | South Kensington | 13 S e p t e m b e r 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAPTAIN S COTT’S COMPASS AND SHACKLETON’S SLEDGING HARNESS INCLUDED IN CHRISTIE’S TRAVEL, SCIENCE AND NATURAL HISTORY SALE Dedicated Polar Sale section commemorates the centenary of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition Herbert George Ponting (1870-1935), Crew of the Terra Nova Captain Robert Falcon Scott, circa 1904-5 Estimate: £1,000-1,500 [lot 123] Estimate: £600-800 [lot 138] South Kensington, London: Christie’s is pleased to announce the forthcoming sale of a selection of art, literature, photographs and artifacts which offer poignant memorials of the lives and endeavours of the celebrated Polar explorer, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, and his contemporaries from the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration. Offered for sale on Tuesday, 9 October 2012, the dedicated Polar section (lots 76-163) of Christie's Travel, Science and Natural History auction to be held in South Kensington is set to commemorate the centenary of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition. The auction will feature historical items relating to the Discovery (1901-1904), Nimrod (1907-1909), Terra Nova (1910-1913), and Endurance (1914-1916) expeditions. Carried by Captain Scott on his sledging journeys, the marching compass used to navigate on both Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions is expected to fetch between £15,000 and £20,000 [lot 91] illustrated right. Inscribed with ink on the cover of the leather case “Capt. ‘Discovery’ 1902”, the item was one of many, returned to Scott’s widow following his final and fatal journey to the South Pole on the Terra Nova expedition. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Master's Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College Follow this and additional works at: http://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Downing, Maggie, "Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South" (2014). Master's Theses. Paper 328. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the City College of New York at CUNY Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of CUNY Academic Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. -

The Tension Between Emotive/Aesthetic and Analytic

Polar Record 53 (270): 245–256 (2017). © Cambridge University Press 2017. doi:10.1017/S003224741700002X 245 The tension between emotive/aesthetic and analytic/scientific motifs in the work of amateur visual documenters of Antarctica’s Heroic Era Pat Millar University of Tasmania ([email protected]) Received June 2016; first published online 9 March 2017 ABSTRACT. Visual documenters made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known were the professional photographers, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of images – photographs and artworks – were also produced by amateurs on lesser known European expeditions and a Japanese one. These amateurs were sometimes designated official illustrators, often scientists recording their research. This paper offers a discursive examination of illustrations from the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899), German Deep Sea Expedition (1898–1899), German South Polar Expedition (1901–1903), Swedish South Polar Expedition (1901–1903), French Antarctic Expedition (1903–1905) and Japanese Antarctic Expedition (1910–1912), assessing their representations of exploration in Antarctica in terms of the tension between emotive/aesthetic and systematic analytic/scientific motifs. Their depictions were influenced by their illustrative skills and their ‘ways of seeing’, produced from their backgrounds and the sponsorship needs of the expedition. Images of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration are artists in the service of science, using scientifically Illustrators made a major contribution to the recording informed observational, technical and aesthetic skills to of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration, providing portray a subject accurately (Hodge 2003: xi). -

Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition

This is a repository copy of Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125438/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Watkins, E orcid.org/0000-0003-2093-6327 (2018) Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. In: MacDonald, LW, Biggam, CP and Paramei, GV, (eds.) Progress in Colour Studies: Cognition, language and beyond. John Benjamins , pp. 441-461. ISBN 9789027201041 https://doi.org/10.1075/z.217.24wat © 2018, John Benjamins. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Progress in Colour Studies: Cognition, language and beyond. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Progress in Colour Studies Conference Proceedings. Amended copy: 30th October 2017 Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. -

The Great White South ! Antarctica, the Blank Continent, the End of the World

The Great White South ! Antarctica, the blank continent, the end of the world. The Antarctic is perhaps the last vacancy, a something which is not nothing. The gaps on our maps have all been filled in, but with its remoteness, its long dark, its freezing dry interior where little but hardy bacteria survive, the pole retains the glamour of terra incognita. It is not an absence, but an empty presence. It is a gap in our busy geographies, a space !open to the imagination. Its vast empty interior is a perfect desert, encircled by the welling life of its coasts. The pleasure we take in stories of the Antarctic rely on the Romantic notion of the sublime. Any polar tale will be replete with experience of the incomprehensible - measureless expanses, unimaginable cold. The effect becomes sublimated, aestheticised, through our distance from the frozen vastness, by our certainty of safety. The pleasure we take in these stories lies in part in the contrast of our comfortable consumption of the narrative - lying on a sunny lawn, seated in the chair by the heater - with the hardships and frigid atmosphere of the pole. The Antarctic is a terrain of the imagination, a storied realm hanging above us like !a dream city. Its very whiteness allows us to project ourselves upon it. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me… … by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation… as in essence whiteness is not so much a colour as the visible absence of colour, and at the same time the concrete of all colours; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows – a colourless, all-colour of atheism from which we shrink? Herman Melville ! Moby Dick The white whale is sign of a godless horror for Ahab, but in being everything and nothing, it is the perfect !repository for imagination. -

Antarctic Connections: Christchurch & Canterbury

Antarctic Connections: Christchurch & Canterbury Morning, Discovery and Terra Nova at the Port of Lyttelton following the British Antarctic (Discovery) Expedition, 1904. (http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/captain-scotts-ships-lyttelton) A guide to the past and present connections of Antarctica to Christchurch and the greater Canterbury region. 1 Compiled by James Stone, 2015. Cover 1 Contents 2 Christchurch – Gateway to the Antarctic 3 Significant Events in Canterbury’s Antarctic History 4 The Early Navigators 5 • Captain James Cook • Sir Joseph Banks • Sealers & Whalers Explorers of the Heroic Age • Captain Robert Falcon Scott 6-9 • Dr Edward Wilson 10-11 • Uncle Bill’s Cabin • Herbert Ponting 12 • Roald Amundsen 13-14 • Sir Ernest Shackleton 15-18 • Frank Arthur Worsley 19 • The Ross Sea Party 20-21 • Sir Douglas Mawson 22 The IGY and the Scientific Age 22 Operation Deep Freeze 23-24 First Māori Connection 25 The IGY and the Scientific Age 26 Hillary’s Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE) 27 NZ Antarctic Heritage Trust 28 • Levick’s Notebook 28 • Ross Sea Lost Photographs 29 • Shackleton’s Whisky 30 • NZ Antarctic Society 31 Scott Base 32 International Collaboration 33 • Antarctic Campus • Antarctica New Zealand • United States Antarctic Program • Italian Antarctic Program 34 • Korean Antarctic Program Tourism 35 The Erebus Disaster 36 Antarctic Connections by location • Christchurch (Walking tour map 47) 37-47 • Lyttelton (Walking tour map 56) 48-56 • Quail Island 57-59 • Akaroa (Walking tour map 61) 60-61 Visiting Antarctic Wildlife 62 Attractions by Explorer 63 Business Links 64-65 Contact 65 Useful Links 66-69 2 Christchurch – Gateway to the Antarctic nzhistory.net.nz © J Stone © J Stone Christchurch has a long history of involvement with the Antarctic, from the early days of Southern Ocean exploration, as a vital port during the heroic era expeditions of discovery and the scientific age of the International Geophysical Year, through to today as a hub of Antarctic research and logistics. -

Analysis of Ponting's Photography

3: Analysis of Ponting’s photography The aim of this study is to address a deficiency in close analysis of Ponting’s images by studying relevant literature, as has been done in Chapter 2, and by examining Ponting’s photographs and film, which will be done now. A visual semiotics methodology is used, based on a combination of discourse analysis (Gee 1990, 2005) and visual analysis (Kress & van Leeuwen 2006). Ponting’s book is also used to enable fuller understanding. Overall, the images and the book form a synergistic relationship, the different codes, visual and verbal, each enhancing the understanding of the other (Hodge & Kress 1983), so that the total effect is greater than the sum of the individual ones. Ponting’s work in Antarctica was different from his previous assignments. While the overall task was similar to that involved in his photography in Japan, India and other lands, Antarctica represented a greater commitment in time, an isolated location, more arduous conditions, and huge technical challenges. In place of local inhabitants, he was depicting a small, highly specialised and purpose- directed microcosm of British society and culture, mostly from naval and scientific contexts, in an uninhabited land. His role in the expedition was functional, but he intended to generate post-expedition income for himself by exhibiting and lecturing on his work, and this influenced his selection of subjects and the way he presented them. There are a very large number of stills, and the focus here is on a representative selection: landscapes, portraits, activities (individual and group, work-related and recreational), and wildlife photographs. -

Terra Nova Expedition

THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST The Heart of the Great Alone : Scott, Shackleton and Antarctic Photography The British Antarctic Expedition, Terra Nova , 1910-13 The turn of the 20th century saw an ‘Heroic Age’ of polar exploration, when the Antarctic continent attracted the attention of governments, scientists and whalers from around the world. Several nations, including Belgium, France, Australia and Japan, launched major expeditions to investigate the region. Britain was among the first to respond to a landmark lecture by Sir John Murray to the Royal Geographical Society in 1893, which called for the thorough and systematic exploration of the southern continent. In 1901, the National Antarctic Expedition made the first extended journey into the interior of Antarctica. The expedition was led by a young naval lieutenant called Robert Scott, and among his crew was Ernest Shackleton, then of the Royal Naval Reserve. In 1909, Scott announced plans to return to the continent with the aim of reaching the South Pole and securing it for Britain. National pride was at stake, and the elusive Pole had still to be claimed. Scott also planned an extensive scientific programme of exploration and research. His ship Terra Nova sailed from Cardiff on 15 June 1910 with a crew that would include the ‘camera artist’ Herbert Ponting, who joined the ship in New Zealand. This was the first time an official photographer and film-maker had joined a polar expedition. Also on board were dogs and ponies, Scott’s preferred means of transport across the ice and snow. In mid-October, news reached the crew that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was also on his way south, with the single-minded intention of reaching the Pole. -

Antarctica University of Wyoming Art Museum, 2007 Educational Packet Developed for Grades K-12

Antarctica University of Wyoming Art Museum, 2007 Educational Packet developed for grades K-12 Purpose of this packet: Question: To provide K-12 teachers with Students will have an opportunity background information on to observe, read about, write the exhibition and to suggest about, and sketch the art works age appropriate applications for in the galleries. They will have exploring the concepts, meaning, an opportunity to listen and and artistic intent of the work discuss the Antarctica exhibition exhibited, before, during, and after with some of the artists and the museum visit. the museum educators. Then, they will start to question the Special note on this exhibit: works and the concepts behind This particular exhibit is dense and the work. They will question rich with interdisciplinary connections the photographic and artistic and issues of the greatest importance techniques of the artists. And, to the earth and its inhabitants, This Eliot Furness Porter (American, 1901-1990), they will question their own curricular unit introduces much Green Iceberg, Livingston Island, Antarctica, 1976, responses to the artists’ work that can be studied in greater detail: dye transfer print, 8-5/16 x 8-1/8 inches, gift of in the exhibition. Further, the the geography of the polar regions, Mr. and Mrs. Melvin Wolf, University of Wyo- students may want to know more the history of Antarctica and polar ming Art Museum Collection, 1984.195.47 about Antarctica, its history exploration, the politics that govern of formation and exploration, this area. Teachers are encouraged to climate, geology, wildlife, animals, plants, environmental use this exhibit of Antarctica – as portrayed by artists – as a effects and scientific experimentation.