Analysis of Ponting's Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbert Ponting and the First Documentary 1

Herbert Ponting And The First Documentary 1 Herbert Ponting And The First Documentary One evening in mid-winter of 1911, in the coldest, most isolated place on earth, some two dozen men of the British Expedition to the South Pole gathered for a slide show. They were hunkered down in a wooden building perched on the edge of Antarctica. For them winter ran from late April to late August. In these four months the sun disappeared entirely leaving them in increasing darkness, at the mercy of gales and blizzards. If you stepped outside in a blizzard, you could become disoriented within a few yards of the hut and no one would know you were lost or where to look for you. On this evening, they were enjoying themselves in the warmth of their well insulated hut. One of their number, who called himself a “camera artist,” was showing them some of the 500 slides he had brought with him to help occupy the long winter hours. The camera artist was Herbert Ponting, a well known professional photographer. In the language of his time he was classified as a “record photographer” rather than a “pictorialist.”i One who was interested in the actual world, and not in an invented one. The son of a successful English banker, Ponting had forsworn his father’s business at the age of eighteen to try his fortune in California. When fruit farming and gold mining failed him, he took up photography, turning in superb pictures of exotic people and places, which were displayed in the leading international magazines of the time. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

The Antarctic Crustal Profile Seismic Project, Ross Sea, Antarctica ALAN K

200,000 years are obviously affected to a lesser degree than argon (40Ar) to excess argon (40ArE) and are, therefore, taken younger samples containing a lower proportion of radiogenic to be a truer representation of the actual age of that particu- _______________________ lar sample. Still, it must be noted that all the 40Ar/ 39Ar ages pro- 40Ar139Ar ages for Mount Erebus as determined in this study duced from Mount Erebus are maximum ages owing to the uncertainty of complete removal (through sample preparation) of all excess argon. 48±9a Excess argon—Too Old Summit phenocrysts Evaluation of these new data Summit phenocrysts -10 179±16a Excess argon—Too Old Summit phenocrysts #2 49±27a Excess argon—Too Old is still in progress; however, it is Summit phenocrysts #2 30-40 641±27a Excess argon—Too Old apparent that our new age deter- Summit (bomb) glass 100 101±16a Excess argon—Too Old minations are significantly Lower Hut flow <1 24±4b Acceptable younger than those previously Three Sisters cones -4 26±2b Acceptable obtained by the conventional Three Sisters cones 11 1±8b Contamination? K/Ar method. The evolution and 36±4 Hoopers Shoulder <1 b Acceptable growth of Mount Erebus may Hoopers Shoulder cone 32±5b Acceptable have been much faster than pre- a Hoopers Shoulder cone -5 94±15 Excess argon viously thought. 42±4b Contamination? Cape Evans This research was supported Cape Evans -5 32±6b Acceptable Cape Royds -2 735b Acceptable by National Science Foundation Cape Royds -20 153±32a Excess argon grant OPP 91-18056. -

Issue 93 (June 2021, Vol.16, No.3)

The Japan Society Review 93 Book, Stage, Film, Arts and Events Review Issue 93 Volume 16 Number 3 (June 2021) The opening review of our June issue explores the Minae is a semi-autobiographical novel using fiction to fascinating life and career of Herbert Ponting, the negotiate issues of nationhood, language, and identity photographer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra between Japan and the US. The Decagon House Murders Nova expedition to the South Pole. Ponting’s travels in by Ayatsuji Yukito is a murder mystery story which follows Japan during the Meiji period are likely to be of particular the universal conventions of this classic genre, while interest to readers and resulted in several photographic bringing to it a distinctively Japanese approach. series and publications including his Japanese memoirs In This issue ends with a review of a publication on Lotus-Land Japan. Japanese wild food plants written by journalist Winifred Another captivating yet very different figure in Bird. From wild mountain and forest herbs to bamboo Japanese culture is the yamamba, the mountain witch, part and seaweed, from Kyushu to Hokkaido, this guide offers of a widely recognised “old woman in the woods” folklore. detailed information on identification, preparation and Reviewed in this issue is a new collective publication recipes to discover and taste this part of the Japanese examining the history and representations of this female natural world. character in terms of gender, art and literature among other topics. Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández Two reviews in this issue focus on literary works recently translated into English. An I-Novel by Mizumura Contents 1) Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Editor Pioneer Filmmake by Anne Strathie Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández 2) Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch Reviewers edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. -

The Collembola of Antarctica1

Pacific Insects Monograph 25: 57-74 20 March 1971 THE COLLEMBOLA OF ANTARCTICA1 By K. A. J. Wise2 Abstract: Subsequent to an earlier paper on Antarctic Collembola, further references and specimen locality records are given, and a new classification is used. Named species and definite distributions are combined in a definitive list of the Collembola of Antarctica. One new synonymy. Hypogastrura viatica (=H. antarctica), is recorded. Collections additional to those reported by Wise (1967) are recorded here, together with further information on some of the species, including one new synonymy. References in the synonymic lists are only those additional to the ones published in my previous paper. As in that paper, S. Orkney Is. and S. Sandwich Is. records are included here, but are excluded from the list of species in Antarctica. In addition to the Bishop Museum collections, specimens from collections of other institutions are recorded as follows: U.S. National Museum, Smithsonian Institution (USNM), British Museum (Nat. Hist.) (BMNH), British Antarctic Survey Biological Unit (BAS), and Canterbury University Antarctic Biology Unit (CUABU). The arrangement of figures and legends are as in Wise (1967). In specimen data a figure at the beginning of a group is the number of micro-slide specimens; a figure at the end, after the col lector's name, is the collector's site number. Classification Classification of the Antarctic species previously (Wise 1967) followed that of Salmon (1964) which radically changed some of the earlier classifications, separating some of the Suborder Arthropleona as distinct families in a new suborder, Neoarthropleona. Since then, Massoud (1967) has published a sound revision of the Neanuridae, in which he has sunk the Suborder Neoarthro pleona establishing the families recorded therein by Salmon as subfamilies or tribes in the Family Neanuridae. -

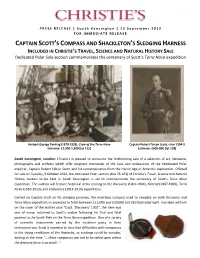

Captain Scott's Compass and Shackleton's Sledging

PRESS RELEASE | South Kensington | 13 S e p t e m b e r 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAPTAIN S COTT’S COMPASS AND SHACKLETON’S SLEDGING HARNESS INCLUDED IN CHRISTIE’S TRAVEL, SCIENCE AND NATURAL HISTORY SALE Dedicated Polar Sale section commemorates the centenary of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition Herbert George Ponting (1870-1935), Crew of the Terra Nova Captain Robert Falcon Scott, circa 1904-5 Estimate: £1,000-1,500 [lot 123] Estimate: £600-800 [lot 138] South Kensington, London: Christie’s is pleased to announce the forthcoming sale of a selection of art, literature, photographs and artifacts which offer poignant memorials of the lives and endeavours of the celebrated Polar explorer, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, and his contemporaries from the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration. Offered for sale on Tuesday, 9 October 2012, the dedicated Polar section (lots 76-163) of Christie's Travel, Science and Natural History auction to be held in South Kensington is set to commemorate the centenary of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition. The auction will feature historical items relating to the Discovery (1901-1904), Nimrod (1907-1909), Terra Nova (1910-1913), and Endurance (1914-1916) expeditions. Carried by Captain Scott on his sledging journeys, the marching compass used to navigate on both Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions is expected to fetch between £15,000 and £20,000 [lot 91] illustrated right. Inscribed with ink on the cover of the leather case “Capt. ‘Discovery’ 1902”, the item was one of many, returned to Scott’s widow following his final and fatal journey to the South Pole on the Terra Nova expedition. -

Scientific Information 2001/2002 Annual New Zealand

Scientific Information 2001/2002 Annual New Zealand Forward Plans LGP The Latitudinal Gradient Project (LGP) is aimed at increasing the understanding of the coastal marine, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems that exist along the Victoria Land coastline in the Ross Sea region, and describing potential environmental variability that may occur in the future. Antarctica New Zealand is providing the logistical capabilities for research camps to be located at specific sites along the Victoria Land coast. Thus, the opportunity to work at particular locations in collaboration with other scientists from various disciplines and National Antarctic Programmes is provided. LGP has been formally incorporated into the SCAR programme RiSCC (Regional Sensitivity to Climate Change). Certain data collected within the LGP will be housed and made available within the RiSCC database framework. Details on how the data will be shared and the timing of when the data will be made available have yet to be decided. It is intended that publications arising from the LGP will be published in a special issue of a refereed journal. Research under the LGP will be both ship-based and land-based. At present, ship-based research, funded under the Ministry of Fisheries’ BioRoss programme and the Italian Antarctic Programme, has been scheduled for January to March 2004 with a research voyage planned using two vessels aimed at supporting near-shore and deep-water marine research. The vessels dedicated to this research are NIWA’s RV Tangaroa, and the Italian Antarctic Programme’s RV Italica. Further information about the ship-based research can be found in the BioRoss research plan and in the BioRoss call for statements of interest. -

Antarctic Magazine September 2016

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 35, No. 1, 2017 35, No. Vol “Hector”: A Sled Dog for Lyttelton Vol 35, No. 1, 2017 Issue 239 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray INDEXER: Mike Wing Antarctic magazine New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 May, 1 August, 1 November, and 1 February. 2 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY “Hector”: A Sled Dog for Lyttelton 2 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership Meteorites and Mishaps in the Deep Field 5 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Я&И@$Ж# ! – A Russian Expletive 8 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more than 15 at any one time. Tribute: William Charles Hopper 10 Current Life Members by the year elected: 1. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 Tribute: James Harvey Lowery 11 2. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 3. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 Tribute: Graham Ernest White 12 4. Arnold Heine (Wellington), 2006 5. Margaret Bradshaw (Canterbury), 2006 “The Discovery” Back Cover 6. Ray Dibble (Wellington), 2008 7. Norman Hardie (Canterbury), 2008 8. Colin Monteath (Canterbury), 2014 9. John Parsloe (Canterbury), 2014 10. Graeme Claridge (Wellington), 2015 11. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Master's Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College Follow this and additional works at: http://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Downing, Maggie, "Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South" (2014). Master's Theses. Paper 328. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the City College of New York at CUNY Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of CUNY Academic Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. -

The Tension Between Emotive/Aesthetic and Analytic

Polar Record 53 (270): 245–256 (2017). © Cambridge University Press 2017. doi:10.1017/S003224741700002X 245 The tension between emotive/aesthetic and analytic/scientific motifs in the work of amateur visual documenters of Antarctica’s Heroic Era Pat Millar University of Tasmania ([email protected]) Received June 2016; first published online 9 March 2017 ABSTRACT. Visual documenters made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known were the professional photographers, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of images – photographs and artworks – were also produced by amateurs on lesser known European expeditions and a Japanese one. These amateurs were sometimes designated official illustrators, often scientists recording their research. This paper offers a discursive examination of illustrations from the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899), German Deep Sea Expedition (1898–1899), German South Polar Expedition (1901–1903), Swedish South Polar Expedition (1901–1903), French Antarctic Expedition (1903–1905) and Japanese Antarctic Expedition (1910–1912), assessing their representations of exploration in Antarctica in terms of the tension between emotive/aesthetic and systematic analytic/scientific motifs. Their depictions were influenced by their illustrative skills and their ‘ways of seeing’, produced from their backgrounds and the sponsorship needs of the expedition. Images of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration are artists in the service of science, using scientifically Illustrators made a major contribution to the recording informed observational, technical and aesthetic skills to of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration, providing portray a subject accurately (Hodge 2003: xi). -

Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition

This is a repository copy of Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125438/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Watkins, E orcid.org/0000-0003-2093-6327 (2018) Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. In: MacDonald, LW, Biggam, CP and Paramei, GV, (eds.) Progress in Colour Studies: Cognition, language and beyond. John Benjamins , pp. 441-461. ISBN 9789027201041 https://doi.org/10.1075/z.217.24wat © 2018, John Benjamins. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Progress in Colour Studies: Cognition, language and beyond. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Progress in Colour Studies Conference Proceedings. Amended copy: 30th October 2017 Mapping the Antarctic: Photography, Colour and the Scientific Expedition in Public Exhibition. -

The First 50 Years of Victoria University of Wellington Antarctic

The First 50 Years of Victoria University of Wellington Antarctic Research Centre Antarctic Expeditions Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand Phone +64-4-463 6587, Fax +64-4-463 5186 E-mail [email protected] www.vuw.ac.nz/antarctic Recollections and reunion programme Victoria University of Wellington 30 June – 1 July 2007 Table of Contents inside front cover Welcome . .2 Recent Benefactors . .3 Reunion programme . .4 Reunion participants . .6 The Birth of VUWAE . .10 Members of VUWAE: 1957-2007 . .12 Recollections of the first 50 years . .18 Victoria University of Wellington Antarctic Expeditions: The First 50 Years Welcome Recent Benefactors Prior to my first departure for the Ice on a VUWAE expedition, I heard the Throughout the history of VUWAE, Harry Keys, Barry Kohn, Phil Kyle, pre-season talk that ARC Director, Professor Peter Barrett claims to have inherited from Bob Clark. organizations and individuals have sponsored Judy Lawrence, Barrie McKelvey, John and supported the programme with equipment Nankervis, Anthony Parker, Russell Plume, “There are basically only two things to remember”, he instructed. “Firstly, help out and money. Most recently the Antarctic Bryan Sissons, David Skinner, Tim Stern, with the boring jobs at Scott Base. This will put you in a good position with base Research Centre has received a $1 million David Sugden, Tony Taylor, John Thurston, staff, which will make their job easier, and will help make the rest of your field donation from former student Alan Eggers, who Colin Vucetich, Trish Walbridge, Robin season go smoothly. Secondly, come back safely.