" What Do I Teach for 90 Minutes?" Creating a Successful Block

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VILLAGE of Mundeleininsider Incorporated in 1909

VILLAGE OF MundeleinINSIDER Incorporated in 1909 WINTER 2015 Message From the Mayor INSIDES As the year winds down, now is the perfect and economic THIS EDITION time to refl ect on our accomplishments development and look forward to what’s ahead for the websites, Village of Mundelein Village of Mundelein in the New Year. rewrote a new Year In Review— sign code, THANK YOU redesig ned 2014-2015 Key Accomplishments 2015 was yet another productive year the Village’s for the Village. Mundelein’s numerous new resident Mundelein Ranked Among the festivals, community events, concerts and packet, and 50 Safest Cities in Illinois special events all exceeded expectations launched a in terms of number of participants, Think Local Police Statue Fund Close to caliber of entertainment and community campaign to Reaching Fundraising Goal engagement. Thank you for your role name just a in helping to make Mundelein a great few initiatives. Every branding decision community in which to live, raise a family, originates from our Brand Promise to Mundelein Honors and enjoy a high quality of life. Please take be “Central Lake County’s premiere Five Businesses with a moment to review some of Mundelein’s location for entrepreneurs and known as a 2015 Gold Star Business Award accomplishments in the “Year In Review” welcoming community.” newsletter article. Pace Dial-A-Ride Service Greatly BIG GRANT PROGRAM Expanding Service Area ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To help revitalize Mundelein, Village I’m proud to acknowledge that Mundelein Trustees approved a Business Incentive once again received the Tree City USA Grant (BIG) program for businesses of all Save The Date! designation. -

The Messenger

IDISTRICT 120 ANNUAL UPDATE MAY 2019 THE MESSENGER Dedicated to academic excellence for all learners through the core values of equity, growth, and collaboration. #mundypride SUPERINTENDENT’S MESSAGE DISTRICT TAX HIGHLIGHTS The district’s overall tax rate has % dropped $.29 since its 2014 high rate. That’s about a 10% reduction in rates. MHS’s overall tax rate is = comparable, lower or much lower than most neighboring Lake County HS districts. Over the past five years, an $ average $300,000 home in the MHS district saw an increase in the total average tax (that the district receives) of about $45 per year. As a percentage of the total property tax bill that’s an average of .004% increase per year. Dr. Myers presents Sol Cabachuela ‘04 with a Distinguished Alumni Award Source: MHS Business Office MUNDELEIN HIGH SCHOOL SHARED SERVICES/ “This way, future Board of Education DISTRICT 120 SHARED SUPERINTENDENT members and superintendents will know TO BEGIN JULY 1 what led to the arrangement and what it 2018-2019 BY THE NUMBERS was intended to accomplish,” she said. The shared services model is set to begin Welcome to our on July 1, 2019. With the retirement of According to the Declaration, the two first annual update District 75 Superintendent Andy Henrikson Boards of Education will seek to uphold which we will begin set for June 30, the boards of education and improve public education for the publishing at the from both Mundelein Elementary District community that will survive beyond their close of each school 75 and Mundelein High School District 120 tenure as board members. -

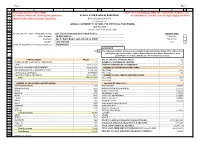

SCHOOL DISTRICT/JOINT AGREEMENT NAME: Lake Zurich Community Unit School District DISTRICT TYPE 10 RCDT NUMBER: 34-049-0950-26 Elementary 11 ADDRESS: 832 S

Page 1 Page 1 A B C D E F G H I J 1 This page must be sent to ISBE Note: For submitting to ISBE, the "Statement of Affairs" can 2 and retained within the district/joint agreement ILLINOIS STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION be submitted as one file to avoid separating worksheets. 3 administrative office for public inspection. School Business Services 4 (217)785-8779 5 ANNUAL STATEMENT OF AFFAIRS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING 6 June 30, 2020 7 (Section 10-17 of the School Code) 8 9 SCHOOL DISTRICT/JOINT AGREEMENT NAME: Lake Zurich Community Unit School District DISTRICT TYPE 10 RCDT NUMBER: 34-049-0950-26 Elementary 11 ADDRESS: 832 S. Rand Road, Lake Zurich, IL 60047 High School 12 COUNTY: Lake County Unit X 1413 NAME OF NEWSPAPER WHERE PUBLISHED: Daily Herald 15 ASSURANCE 16 YES X The statement of affairs has been made available in the main administrative office of the school district/joint agreement and the required Annual Statement of Affairs Summary has been published in accordance with Section 10-17 of the School Code. 1817 19 CAPITAL ASSETS VALUE SIZE OF DISTRICT IN SQUARE MILES 20 20 WORKS OF ART & HISTORICAL TREASURES 0 NUMBER OF ATTENDANCE CENTERS 8 21 LAND 11,953,158 9 MONTH AVERAGE DAILY ATTENDANCE 5,218 22 BUILDING & BUILDING IMPROVEMENTS 82,608,453 NUMBER OF CERTIFICATED EMPLOYEES 23 SITE IMPROVMENTS & INFRASTRUCTURE 7,236,729 FULL-TIME 519 24 CAPITALIZED EQUIPMENT 5,972,667 PART-TIME 27 25 CONSTRUCTION IN PROGRESS 37,055,097 NUMBER OF NON-CERTIFICATED EMPLOYEES 26 Total 144,826,104 FULL-TIME 198 27 PART-TIME 76 28 NUMBER OF PUPILS ENROLLED -

Hawthorn Woods Country Club COMMUNITY GUIDE Copyright 2004 Toll Brothers, Inc

A GUIDE TO THE SERVICES AVAILABLE NEAR YOUR NEW HOME Hawthorn Woods Country Club COMMUNITY GUIDE Copyright 2004 Toll Brothers, Inc. All rights reserved. These resources are provided for informational purposes only and represent just a sample of the services available for each community. Toll Brothers in no way endorses or recommends any of the resources presented herein. CONTENTS COMMUNITY PROFILE . .1 SCHOOLS . .2 CHILD CARE/PRE-SCHOOL . .3 SHOPPING . .3 MEDICAL FACILITIES . .4 VETERINARIANS . .4 PUBLIC UTILITIES/GENERAL INFORMATION . .4 WORSHIP . .5 TRANSPORTATION . .6 RECREATIONAL FACILITIES – LOCAL . .7 RECREATIONAL FACILITIES – REGIONAL . .8 RESTAURANTS . .9 LIBRARIES . .10 COLLEGES . .10 SOCIAL SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS . .11 GOVERNMENT . .11 SENIOR CITIZEN CENTER . .12 ASSISTED LIVING . .12 EMERGENCY NUMBERS . .12 LEARN ABOUT THE SERVICES YOUR COMMUNITY HAS TO OFFER PROFILE The Village of Hawthorn Woods holds a rich heritage of tradition, founded by a sense of community. In the 1700’s, French explorers arrived in the area. At the time, the area was home to the Potawatami Indians. The friendly and helpful Potawatami welcomed and assisted the new settlers in adapting to the environment. In 1839, Lake County was created by the Illinois State Legislature. The beautiful Village of Hawthorn Woods was incorporated into Lake County in 1958. Today, the Village of Hawthorn Woods is predominately residential, with more than 2,300 homes spread over 5.4 miles. The Village strives to preserve a sense of community with a quaint atmosphere, open space and the rural character that brought the first settlers here long ago. There are three outstanding school districts, as well as several private schools, that service the area to provide a superior educational experience. -

LAKE COUNTY Resource Guide with Assistance From

LAKE COUNTY Resource Guide With assistance from: This guide is a working document that is meant to serve as a resource toolkit/handout for community members to prepare for Administrative Relief Implementation. Please send us information about community organizations and the resources that might be missing or have incorrect information – [email protected]. Thanks for working with us! Thanks, Julián Lazalde Policy Analyst 2 Table of Contents IMMIGRANT RESOURCE ORGANIZATIONS Fr. Gary Graf Center……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 HACES…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Mano a Mano Family Resource Center……………………………………………………………………………….. 3 LOCAL GOVERNEMENT OFFICES Assessor……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Clerk of the 19th Circuit Court……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Courts and Court Services…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3-4 Department of Human Services………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4-5 Illinois Secretary of State……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Libraries……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 5-6 Municipal Offices………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 6-10 Office of the Public Defender……………………………………………………………………………………………… 10-11 Park District Offices……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11-12 Recorder of Deeds……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 State’s Attorney’s Office…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 12 Townships………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 12-14 LAW ENFORCEMENT & SAFETY Fire Departments………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

June 8, 2020 It Is with a Heavy Heart

June 8, 2020 It is with a heavy heart that representatives from the North Suburban Conference (NSC) member schools, which include Lake Forest High School, Lake Zurich High School, Libertyville High School, Mundelein High School, Adlai E. Stevenson High School, Warren Township High School, Waukegan High School, and Zion-Benton Township High School, reach out to you today. We acknowledge that the events that have transpired over the last few months have been an emotional time for our student-athletes, parents, and coaches. The loss of sports activities, time with teammates and coaches, coupled with the lack of a regular routine have been challenges for everyone involved. The Illinois High School Association (IHSA), released an updated statement on Friday, June 5th stating specifics for activities that can be held during Restore Illinois Phase 3. We anticipate receiving more guidance from the IHSA in the days ahead, which will guide our decisions regarding a return to sport- specific activities in the future. The NSC is committed to ensuring the health and safety of our student- athletes. In response to recent events of social injustice, we want to emphasize that the NSC promotes diversity and inclusivity and we will continue to use our platform to spread this message and support all of our student-athletes. Racism, violence, and injustice have no place in our community and will not be tolerated. The North Suburban Conference will continue its work to dismantle the biases that exist and use the power of education and co-curricular opportunities to positively shape the future. In the near future, we will be sharing an opportunity for student-athletes from our member schools to participate in a virtual NSC meeting to share their feelings and insights into how the NSC can become an agent for change. -

Lake Forest High School Parent- Athlete Handbook & Scout Trails

2018 - 2019 LAKE FOREST HIGH SCHOOL PARENT- ATHLETE HANDBOOK & SCOUT TRAILS 1 Contents LAKE FOREST HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT .......................................................................................................... 3 MISSION STATEMENT .................................................................................................................................................... 3 PHILOSOPHY .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 GOALS ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 GETTING TO KNOW THE LAKE FOREST HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC PROGRAM ....................................................................... 4 Sports at Lake Forest High School ................................................................................................................................. 4 North Suburban Conference ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Lake Forest High School Sport Season Start Dates ...................................................................................................... -

LHS Parent Athlete Handbook 2019-2020

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBERTYVILLE ATHLETIC HANDBOOK This handbook has been prepared to make information and suggestions readily available to you and your parents helping to make your athletic career here at LHS more successful. This handbook should serve as a source of information and guidelines for the operation of our programs. It is the intent of the LHS Athletic Department that no person shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation or be denied benefits or subjected to discrimination under the educational program or activities described herein. In addition District #128 ensures equal opportunities to all students regardless of race, sex, color, national origin, religion or handicap under the by-laws of the IHSA and the North Suburban League. You will receive this athletic handbook once during your high school career. This is your only copy. Please read the material this handbook contains as you will be held responsible for the contents. Each incoming freshman student will receive a copy along with those student athletes who have transferred to Libertyville High School. Each head coach may establish additional, individual sports rules for his/her team regarding attendance at practice sessions, personal conduct, and personal appearance. These rules must be distributed to team members at or before tryouts and must be on file at the Athletic Office. We would also like to remind you that participating in our athletic programs is a privilege and that along with this privilege is a tremendous responsibility. Be aware that you will be in the spotlight on and off of the field. Your image will reflect the perception to people of what our team, community and school is all about. -

COURSE SELECTION Dear Parents/Guardians

COURSE SELECTION Dear Parents/Guardians: We believe that educational planning and the selection of classes is one of the most important parts of your student’s high school experience, and we hope you will take an active part in the process. The Course Guide contains information on graduation requirements, Common Core State Standards, NCAA Clearinghouse requirements, and every course offered at Mundelein High School. It lists the following for each course: prerequisites, grade level criteria, number of terms, number of credits, and the course description. In addition, Mundelein High School frames course selection in the context of Programs of Study. Please take time to review and discuss the Programs of Study with your son/daughter, so that our students choose courses that align with their post-secondary plans. Each student will receive a Course Selection Worksheet; this worksheet lists every course offered next year for each grade level, along with the number of terms the course meets. Next to the department heading is a corresponding page number in the Course Guide. Freshmen, sophomores, and juniors are required to fill 7 periods for the year. Beginning in December, counselors will schedule individual appointments with each student. During the appointments, counselors will review graduation requirements, record course selections, and discuss post- high school plans. Please contact our Guidance Department at 949-2200 if you have any questions. We look forward to working closely with you and your students to plan for an exciting and challenging 2018-2019 school year. Best Regards, Dr. Anthony Kroll Principal GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS To graduate from Mundelein High School, students must complete 17 core academic requirements listed below and additional elective credits to meet the overall graduation requirement. -

Countryside Turf Club

COUNTRYSIDE TURF CLUB 17-ACRE HORSE FARM 21989 W. HAWLEY STREET HAWTHORN WOODS, IL 60060 PRESENTED BY: Anne R. Dempsey 847-698-8269 Office [email protected] MARCH 8, 2010 OFFERING PACKAGE COUNTRYSIDE TURF CLUB - 17 ACRE HORSE FARM 21989 W. HAWLEY STREET, HAWTHORN WOODS, IL 60060 OFFERING HIGHLIGHTS Countryside Turf Club is a premier Hunter/Jumper facility in Hawthorn Woods, IL. Current Boarders • 17 Horses – Countryside Turf Club Boarders • 24 Stalls – Available (North Aisle) • 18 Stalls – Available All horses are on month-to-month boarding agreements. PROPERTY PROFILE • Surrounded by beautiful homes in the fabulous Steeple Chase golf and equestrian community • Current owner has owned and developed the Steeple Chase community and the Countryside Turf Club since 1990. • Main Barn – approximately 30,000 s.f. • Main Barn – 66 stalls - 39 stalls (14 x 14 with automatic waterers), 27 stalls (12 x 12) • Maintenance Building – approximately 9,720 s.f. • Maintenance Building – 12 stalls (12 x 12) • Fire sprinkler system - entire facility including the indoor arena and all aisles and stalls • 24-hour security on premise. • 4 tack rooms, a viewing room and 2 wash racks with hot and cold water. • Laundry Facilities • Extra large aisles covered with rubber matting, • Entire facility heated during the winter months. • Indoor arena is 80 x 170 feet • Outdoor dressage is 120 x 200 feet • Outdoor jump arena is 150 x 250 • (13) Paddocks • Five acre hay field SALE PRICE - $3,000,000 PROPERTY TAXES - $8,731 (2008) www.countrysideturfclub.com COLLIERS BENNETT & KAHNWEILER INC . | 1 OFFERING PACKAGE COUNTRYSIDE TURF CLUB - 17 ACRE HORSE FARM 21989 W. -

Village of Hawthorn Woods Staff Directory

Village of Hawthorn Woods Staff Directory VILLAGE HALL 2 Lagoon Drive Open Monday – Friday, 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Ph: (847) 438-5500 Fx: (847) 438-1459 www.vhw.org ADMINISTRATION Name Title Phone # Pamela Newton Chief Operating Officer (847) 847-3535 Donna Lobaito Chief Administrative Officer/Village Clerk (847) 540-5222 Max Gonzalez Administrative Intern (847) 847-3594 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Name Title Phone # Wayne Wehde Building Inspector/Code Enforcement Officer (847) 847-3588 Karen Baker Building Division Specialist (847) 847-3586 Amy Belmonte Building Division Specialist (847) 847-3537 FINANCE AND HUMAN RESOURCES Name Title Phone # Kristin Kazenas Chief Financial Officer/Human Resources Director (847) 847-3590 Danette Russell Finance Specialist (847) 847-3529 PARKS AND RECREATION Name Title Phone # Brian Sullivan Director of Parks & Recreation (847) 847-3531 Amy Mason Assistant Director of Parks & Recreation (847) 847-3533 PUBLIC WORKS 35 Old McHenry Road Monday – Friday, 7:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Ph: (847) 540-5227; Fx: (847) 540-5237 Name Title Phone # Erika Frable Director of Public Works (847) 540-5223 Matthew Bartlett Assistant Director of Public Works (847) 540-5228 Kelley Foster Administrative Assistant (847) 540-5227 AQUATIC CENTER 94 Midlothian Drive Open Memorial Day thru Labor Day Name Title Phone # Alex Casler* Aquatic Center Manager (847) 847-3539 * Contact for Room Rentals Front Desk (847) 847-3504 Local Ordinances You Should Know Business Registration a national holiday. The use of a stationary or portable All businesses in the Village are required to be registered. electronic sound reinforcement and/or sound reproduction A home-based or commercial business license should system utilizing loudspeakers that is audible from a distance be purchased every January of the calendar year. -

Thursday, October 10 11:30-2:30 MHS GYMNASIUM

Mundelein High School Third Annual Thursday, October 10 11:30-2:30 MHS GYMNASIUM All MHS Seniors are invited to apply to the 29 attending colleges for free – yes, every college attending is offering a FREE application to MHS seniors on Thursday, October 10th during all lunch periods! There is no limit to the number of applications a student can fill out, but we strongly encourage students to only apply to schools that they are genuinely interested in. To help you make your decision, we have created this booklet with information about each of the schools who will be attending. What do I need to bring? Your charged Chromebook o Most applications will be completed online o You can definitely have the application nearly complete and ready to hit “submit.” As long as you click that button with the representative on this day, the app is FREE. o Go to the school’s website to find their application and view it prior to the event if you want to be as prepared as possible. A copy of your SAT or ACT score report o Print these from your account at either collegeboard.org or actstudent.org A copy of your transcript o Ask your counselor or stop by the CCRC o We will be available to print these the day of the event as well A smile o This is not an interview, but be polite and dress neatly o Thank the representative for coming in to work with you and provide a free application! Vocabulary Used in the Following Pages Size of the school: This is the undergraduate population.