DISAPPEARANCES Disappeared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Regional Views on South Asian Co-Operation with Special Reference to Development and Security Perspectives in India and Shri Lanka

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Northi Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Results of Parliamentary General Election - 1947

RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - 1947 No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted No of No of Total No. of Votes No of Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 1 Colombo North George R. de Silva Umbrella 7,501 189 14,928 30,791 Lionel Cooray Elephant 6,130 E.C.H. Fernando Cup 501 A.P. de Zoysa House 429 H.C. Abeywardena Hand 178 2 Colombo Central A.E. Goonasinha Bicycle 23,470 3,489 102,772 55,994 T.B. Jayah Cart Wheel 18,439 Pieter Keuneman Umbrella 15,435 M.H.M. Munas House 8,600 Mrs. Ayisha Rauff Tree 8,486 V.J. Perera Elephant 5,950 V.A. Sugathadasa Lamp 4,898 G.W. Harry de Silva Pair of Scales 4,141 V.A. Kandiah Clock 3,391 S. Sarawanamuttu Chair 2,951 P. Givendrasingha Hand 1,569 K. Dahanayake Cup 997 K. Weeraiah Key 352 K.C.F. Deen Star 345 N.R. Perera Butterfly 259 3 Colombo South R. A. de Mel Key 6,452 149 18,218 31,864 P. Sarawanamuttu Flower 5,812 Bernard Zoysa Chair 3,774 M.G. Mendis Hand 1,936 V.J. Soysa Cup 95 Page 1 of 15 RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - 1947 No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted No of No of Total No. of Votes No of Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 4 Wellawatta-Galkissa Colvin R. de Silva Key 11,606 127 21,750 38,664 Gilbert Perera Cart Wheel 4,170 L.V. -

RESULTS of PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - May 27, 1970 No of No of Total No

RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - May 27, 1970 No of No of Total No. of Votes No of No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 1 Colombo North V.A. Sugathadasa Elephant 20,930 97 44,511 Harris Wickremetunge Chair 13,783 W.I.A. Corsby Fernando Ship 164 A.S. Jayamaha Cockerel 97 2 Colombo Central R. Premadasa Elephant 69,310 5,491 240,597 99,265 Falil Caffoor Chair 63,624 Pieter Keuneman Star 58,557 M. Haleem Ishak Hand 41,716 C. Durairajah Umbrella 783 M. Haroun Careem Bell 413 Poopathy Saravanamuttu Ship 396 Panangadan Raman Krishnan Pair of Scales 307 3 Borella Kusala Abhayawardana (Mrs.) Key 16,421 50 32,810 42,849 M.H. Mohamed Elephant 15,829 M.A. Mansoor Pair of Scales 510 4 Colombo South J.R. Jayawardena Elephant 57,609 1,134 97,928 66,136 Bernard Soysa Key 36,783 Ratnasabapathy Wijaya Indra Eye 1,166 Ariyadasa Peiris Bell 561 A.S. Jayamaha Cockerel 241 Mudalige Justin Perera Flower 165 Joseph Beling Chair 164 Yathiendradasa Manampery Pair of Scales 105 5 Wattala A.D.J.L. Leo Hand 21,856 106 41,629 48,875 D. Shelton Jayasinghe Elephant 19,667 6 Negombo Denzil Fernando Elephant 20,457 132 36,509 44,284 Justin Fernando Hand 15,920 RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - May 27, 1970 No of No of Total No. of Votes No of No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 7 Katana K.C. -

Baila and Sydney Sri Lankans

Public Postures, Private Positions: Baila and Sydney Sri Lankans Gina Ismene Shenaz Chitty A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Contemporary Music Studies Division of Humanities Macquarie University Sydney, Australia November 2005 © Copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF F IG U R E S.......................................................................................................................................................................... II SU M M A R Y ......................................................................................................................................................................................Ill CER TIFIC ATIO N ...........................................................................................................................................................................IV A CK NO W LED GEM EN TS............................................................................................................................................................V PERSON AL PR EFA C E................................................................................................................................................................ VI INTRODUCTION: SOCIAL HISTORY OF BAILA 8 Anglicisation of the Sri Lankan elite .................... ............. 21 The English Gaze ..................................................................... 24 Miscegenation and Baila............................................................ -

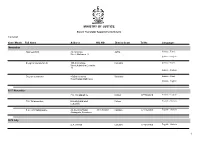

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka May 2007

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 11 MAY 2007 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 11 MAY 2007 SRI LANKA Contents PREFACE Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 APRIL 2007 TO 30 APRIL 2007 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 AND 30 APRIL 2007 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources.............................................................................. 4.21 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

Sri Lanka's Human Rights Crisis

SRI LANKA’S HUMAN RIGHTS CRISIS Asia Report N°135 – 14 June 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................ i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. HOW NOT TO FIGHT AN INSURGENCY ............................................................... 2 III. A SHORT HISTORY OF IMPUNITY......................................................................... 4 A. THE FAILURE OF THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM...................................................................................4 B. COMMISSIONS OF INQUIRY......................................................................................................5 C. THE CEASEFIRE AND HUMAN RIGHTS......................................................................................6 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE NEW WAR............................................................... 7 A. CIVILIANS AND WARFARE ......................................................................................................7 B. MASSACRES...........................................................................................................................8 C. EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS ......................................................................................................9 D. THE DISAPPEARED ...............................................................................................................10 E. ABDUCTIONS FOR RANSOM...................................................................................................11 -

Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability

International Human Rights Law Journal Volume 1 Issue 1 DePaul International Human Rights Law Article 2 Journal: The Inaugural Issue 2015 Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability Mytili Bala Robert L. Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow at the Center for Justice and Accountability, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/ihrlj Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Geography Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Bala, Mytili (2015) "Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability," International Human Rights Law Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/ihrlj/vol1/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Human Rights Law Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability Cover Page Footnote Mytili Bala is the Robert L. Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow at the Center for Justice and Accountability. Mytili received her B.A. from the University of Chicago, and her J.D. from Yale Law School. The author thanks the Bernstein program at Yale Law School, the Center for Justice and Accountability, and brave colleagues working for accountability and post-conflict transformation in Sri Lanka. -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Amba Yahaluwo by T.B. Ilangaratne AMBA YAHALUWO PDF

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Amba Yahaluwo by T.B. Ilangaratne AMBA YAHALUWO PDF. Sirimavo Bandaranaike Leader of the Opposition: This article needs additional citations for verification. See 1 question about Amba Yahaluwo…. Galagedera Vidyalaya, GalagederaSt. The socio-economic classifications that surrounding them will n I loved the Sinhala novel, loved the Akba series and also loved the English translation which I borrowed from a student. Open Preview See a Problem? Celebrating Kandyan middle-class life”. Truly a wonderful a “coming of age” novel. Ilangaratne retired from politics on April 12, Abdul Cader Lakshman Kiriella M. Selvanayagam Senerath Somaratne S. Amba Yahaluwo by T.B. Ilangaratne. Siriwardena Bernard Soysa V. Feb 20, Thevuni Kotigala rated it it was amazing. Thanuja rated it it was amazing Jan 19, To ask other readers questions about Amba Yahaluwoplease sign up. Retrieved from ” https: Abdul Raheem rated yaaluwo really liked it Feb 01, Apr 24, Keshavi added it. T. B. Ilangaratne. Jul 21, Isini Thisara added it. Nadun Lokuliyanage rated it it was amazing Apr 30, Amba Yahaluwo was made into a television serial. Retrieved 19 May Hasini Anjala rated it liked it Jul 01, Nilu rated it it was amazing Feb 16, I loved the Sinhala novel, loved the TV series and also loved the English translation which I borrowed from a student. This is a wonderful story about two children To ask other readers questions about Amba Yahaluwoplease sign up. The socio-economic classifications that surrounding them will never let them be friend as they want to. Sanath Senarathne rated it liked it Oct 14, But if I had been able to translate it while Mr. -

Chapter Iv Sri Lanka and the International System

1 CHAPTER IV SRI LANKA AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM : THE UNP GOVERNMENTS In the system of sovereign states, individual states interact with other states and international organizations to protect and promote their national interests. As the issues and scope of the interests of different classes of states vary, so do the character and patterns of their interactions to preserve and promote them. Unlike the super powers whose national interests encompass the entire sovereign states system, the small states have a relatively limited range of interests as well as a relatively limited sphere of foreign policy activities. As a small state, Sri Lanka has a relatively small agenda of interests in the international arena and the sphere of its foreign policy activities is quite restricted in comparison to those of the super powers, or regional powers. The sphere of its foreign policy activities can be analytically separated into two levels : those in the South Asian regional system and those in the larger international system.1 In the South Asian regional system Sri Lanka has to treat India with due caution because of the existence of wide difference in their respective capabilities, yet try to maintain its sovereignty, freedom and integrity. In the international system apart from mitigating the pressures and pulls emanating from the international power structure, Sri Lanka has to promote its national interests to ensure its security, stability and status. Interactions of Sri Lanka to realize its national interests to a great extent depended upon the perceptions and world views of its ruling elites, which in its case are its heads of governments and their close associates.2 Although the foreign policy makers have enjoyed considerable freedom in taking initiatives in the making and conduct of foreign policy, their 2 freedom is subject to the constraints imposed by the domestic and international determinants of its foreign policy.