Ambivalent Traditions: Transforming Gender Symbols and Food Practices in the Czech Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Czech Republic

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 11/19/2018 GAIN Report Number: EZ1808 Czech Republic Exporter Guide Czech Republic: Exporter Guide 2018 Approved By: Emily Scott, Agricultural Attaché Prepared By: Martina Hlavackova, Marketing Specialist Report Highlights: This exporter guide provides practical tips for U.S. exporters on how to conduct business in the Czech Republic. Although a small market, the country serves as an entry point for companies expanding to the developing markets in the east. With one of the fastest growing economies in the EU and the booming tourist industry, the Czech Republic offers opportunities for U.S. exporters of fish and seafood, dried nuts, food preparations, distilled spirits, wine, and prime beef. Exporter Guide Czech Republic 2018 Market Fact Sheet: Czech Republic_______________________________ Executive Summary Though with only a population of 10.6 million, the Czech Quick Facts CY 2017 Republic is one of the most prosperous and industrialized economies in Central Europe and serves as an entry point for Imports of Consumer-Oriented Products (USD) U.S. companies expanding beyond traditional markets in $ 4.87 billion* Western Europe to the developing markets in the east. As an EU member, the Czech market complies with EU market entry List of Top 10 Growth Products Imported from the regulations. US In 2017, the Czech economy was one of the fastest growing 1. Frozen Hake and Alaskan Pollock economies in Europe and grew by a robust 4.5 percent. -

Eat Smart Move a Lot Comenius Project (2011-2013

EEATAT SSMARTMART MMOVEOVE A LLOTOT CCOMENIUSOMENIUS PPROJECTROJECT ((2011-2013)2011-2013) HHEALTHYEALTHY RECIPIESRECIPIES BBOOKLETOOKLET This project has been funded with support from the European Commission, grant [2011-1-TR1-COM06-24050-1.] This booklet reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. or watched the procedure of making noodles in the market place in Turkey, INTRODUCTION saw the sea and ancient sights in Greece, went hiking in autumn-colored Beskydy, baked at the school training kitchen in the Czech Republic, visited beautiful Rome and danced salsa in Italy, explored the salt mines in Poland. During the days we spent at each project school, we could compare our school systems and teaching methods as well as learn something about our ways of life. The project has inspired many teachers to promote a healthy lifestyle. In some schools grants of physical education were strengthened. The most important in our project were opportunities to meet new friends among students and teachers, show them some places of interest in our countries, regions and schools. We all were enthusiastic about the cooperation. There were plenty of tears when our last day came and we had to say good bye. We will never forget the days spent with our new friends and we hope to visit our wonderful countries again in the future. Now finally we are here to show our final product. This book was EAT SMART MOVE A LOT... written by the participants who were involved in multilateral school partnership programme Comenius among six European schools PARTNER SCHOOLS Our journey started two years ago when we first found each other from Turkey, the Czech Republic, Poland, Greece, Italy, Romania. -

Czech Cuisine Contents

Czech Cuisine Contents GOING BACK IN TIME 2 I. Hors d’Oeuvres 7 II. Soups 8 III. Main Courses 10 MEAT DISHES 10 Beef 10 Mutton/Lamb 12 Pork 13 Poultry 15 Fish 16 Game 17 MEATLESS DISHES 18 IV. Sweet Dishes and Desserts 21 V. Side Dishes 24 VI. Small Dishes 26 VII. Cheese 27 VIII. Beverages 28 IX. Some Useful Advice 35 Come and taste! www.czechtourism.com Introduction Travelling is by far the best way to acquaint oneself with different countries. Needless to say getting to know the basic features of the culture and traditions of the visited country also involves tasting the specialities of its national cuisine. Sometimes this may require some courage on the visitor's part, sometimes it may provide agreeable palate sensations to be remembered for years. In our opinion, a piece of expert advice may always come in handy. And this is the aim of the publication you have in your hands. Going Back in Time Nature has been generous to the original inhabitants of the Czech Republic giving them a wealth of gifts to live on, including an abundance of fish in the rivers and game in the forests, as well as fertile fields. Besides that, poultry, cattle and sheep breeding throve in the Czech lands. Popular meals included soups, various kinds of gruel and dishes prepared from pulses. The Czech diet was varied and substantial, and before long it was supplemented by beer and wine since vine-grapes have from time immemorial been cultivated successfully in the warm climate of the Moravian and Bohemian lowlands. -

St. Petersburg

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels St. Petersburg October - November 2014 Mellow Yellow Autumn beyond the city limits More than 10 years in Russia! Fine dining and great view Discover the world of Buddha-Bar inyourpocket.com N°97 Contents Where to eat 28 ESSENTIAL Restaurants in hotels 42 CIT Y GUIDES Nightlife 45 Foreword 4 What to see 48 The Essentials 48 In the News 5 Hermitage 49 Arrival & Getting Around 6 St. Petersburg’s historical outskirts 52 Old Soviet Tours 54 City Basics 8 Where to stay 55 Language 9 Interview with concierge 56 Culture & Events 10 Shopping 58 Concerts and festivals 10 Russian souvenirs 58 Russian rock 16 Live music clubs 18 Expat & Business 60 Exhibitions 20 The Expat Experience 60 Features Maps & Index St. Petersburg theatre life 22 City map 62 Krestovsky and Yelagin Islands 24 Street index 64 Historic dining 35 Metro map 67 Konyushennaya area 43 Moscow 65 0+ www.facebook.com/StPetersburgInYourPocket October - November 2014 3 Foreword In the News Across the meadows whirling blow The yellow leaves of fall; HAPPY UNITY DAY PETROVSKAYA AQUATORIA No verdure in the woodlands now, November 04 is Russia’s Day of Popular Unity. This national September is traditionally associated with education and The dark green pine is all. holiday is a new old holiday having been celebrated for knowledge so what better time to hold the grand open- Beneath the boulder’s hanging crest, the first time in 1649 and commemorates the victorious ing of the historical theatrical scale model “Petrovskaya St. Petersburg In YourESSENTIAL Pocket No more on beds of flowers uprising in 1612 by Minin and Pozharsky which ejected Aquatoria”? This new unique exhibition is dedicated to founded and publishedCI TbyY OOO GUIDES Krasnaya Shapka/In Your Pocket. -

Czech Republic

CZECH REPUBLIC Capital: Prague Language: Czech Population: 10.5 million Time Zone: EST plus 6 hours Currency: Czech Koruna (CZK) Electricity: 220V. 50Hz Fun Facts • Czech people are the world's greatest consumers of beer pro capita • The Czech Republic became a member of N.A.T.O. in 1999 and of the European Union in 2004 • The Czech Republic is the second-richest country (after Slovenia) of the former Communist Bloc The Czech Republic boasts a magnificent heritage of castles, medieval towns, palaces, churches, and above all, its romantic capital, "Golden" Prague. It is a relatively small country in Central Europe (30,000 sq. miles) composed of Moravia with its endless fields and vineyards, Bohemia, which is highly industrialized but also famous for its beers, and Moravian Silesia with its iron industry and coal mines. All over the Czech Republic you can visit many elegant spa cities. For over 1,500 years, the history of the Slavic Czechs (the name meaning "member of the clan") was influenced by contacts with their western, German neighbors. According to popular belief from ancient times, the Slavic Premysl royal family was replaced by the Luxemburg family in the first half of the 14th century after assassination of the king Wenceslas III. Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, brought prosperity to the land. Jan Hus, the early church reformer who was burned at the stake for heresy, founded the first Reformed church here almost 100 years before the Lutherans. The Hapsburgs started to rule the state from the first half of the 16th century; they managed to quell the Protestant spirit of the nation temporarily but were powerless against the surge of national feelings in the 19th century, which resulted in the foundation of Czechoslovakia following WWI—a foundation which lasted for 74 years (until the end of 1992). -

To View Online Click Here

GCCL TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE Grand European Cruise 2022 Learn how to personalize your experience on this vacation Grand Circle Cruise Line® The Leader in River Cruising Worldwide 1 Grand Circle Cruise Line ® 347 Congress Street, Boston, MA 02210 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. Soon, you’ll once again be discovering the places you’ve dreamed of. In the meantime, the enclosed Grand Circle Cruise Line Travel Planning Guide should help you keep those dreams vividly alive. Before you start dreaming, please let me reassure you that your health and safety is our number one priority. As such, we’re requiring that all Grand Circle Cruise Line travelers, ship crew, Program Directors, and coach drivers must be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 at least 14 days prior to departure. Our new, updated health and safety protocols are described inside. The journey you’ve expressed interest in, Grand European Cruise River Cruise Tour, will be an excellent way to resume your discoveries. It takes you into the true heart of Europe, thanks to our groups of 38-45 travelers. Plus, our European Program Director will reveal their country’s secret treasures as only an insider can. You can also rely on the seasoned team at our regional office in Bratislava, who are ready to help 24/7 in case any unexpected circumstances arise. Throughout your explorations, you’ll meet local people and gain an intimate understanding of the regional culture. Enter the home of a local family in Wertheim for a Home-Hosted Kaffeeklatsch where you will share coffee and cake, and experience what life is like for a typical German family; and chat with a member of Serbia’s Roma community to gain insight into the stigma facing this culture in Europe—and how they are paving the way for a new future for their people. -

Traditional Foods in Europe- Synthesis Report No 6. Eurofir

This work was completed on behalf of the European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR) Consortium and funded under the EU 6th Framework Synthesis report No 6: Food Quality and Safety thematic priority. Traditional Foods Contract FOOD – CT – 2005-513944. in Europe Dr. Elisabeth Weichselbaum and Bridget Benelam British Nutrition Foundation Dr. Helena Soares Costa National Institute of Health (INSA), Portugal Synthesis Report No 6 Traditional Foods in Europe Dr. Elisabeth Weichselbaum and Bridget Benelam British Nutrition Foundation Dr. Helena Soares Costa National Institute of Health (INSA), Portugal This work was completed on behalf of the European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR) Consortium and funded under the EU 6th Framework Food Quality and Safety thematic priority. Contract FOOD-CT-2005-513944. Traditional Foods in Europe Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 What are traditional foods? 4 3 Consumer perception of traditional foods 7 4 Traditional foods across Europe 9 Austria/Österreich 14 Belgium/België/Belgique 17 Bulgaria/БЪЛГАРИЯ 21 Denmark/Danmark 24 Germany/Deutschland 27 Greece/Ελλάδα 30 Iceland/Ísland 33 Italy/Italia 37 Lithuania/Lietuva 41 Poland/Polska 44 Portugal/Portugal 47 Spain/España 51 Turkey/Türkiye 54 5 Why include traditional foods in European food composition databases? 59 6 Health aspects of traditional foods 60 7 Open borders in nutrition habits? 62 8 Traditional foods within the EuroFIR network 64 References 67 Annex 1 ‘Definitions of traditional foods and products’ 71 1 Traditional Foods in Europe 1. Introduction Traditions are customs or beliefs taught by one generation to the next, often by word of mouth, and they play an important role in cultural identification. -

Examples of Typical Czech Cuisine

EXAMPLES OF TYPICAL CZECH CUISINE Prague ham with freshly ground horseradish - Prague pork ham is a very saucy ham on the bone. It is covered with a thin layer of fine fat, partly with skin. It is marinated in brine for 2 – 3 weeks. Then it is smoked until it acquires a golden colour and this is followed by simmering at a temperature of 75°C for five hours, in order to achieve the right juicy consistence. Strong beef stock with traditional liver dumplings, noodles and root vegetables - It is always made of beef meat and marrow bones, root vegetables and wild spices, this mixture is simmered for as long as 12 hours. Liver dumplings made of beef liver, garlic, marjoram and eggs are added to the soup together with homemade manually cut noodles. Sirloin in cream sauce with cranberries, bread dumplings and Carlsbad dumplings - Czech gastronomy jewel made of juicy beef tenderloin interlarded with fine bacon, prepared on vegetable basis with spices and cream. It is served with fluffy bread dumplings. All this culinary work of art is decorated with cranberries. Marshal Radetzky goulash, served with bacon dumplings and chopped parsley - Czech beef goulash, optimally made of hind shank, combining taste of juicy meat with the flavour of pepper, paprika, garlic and marjoram. It is served with bacon dumplings or just with freshly baked bread. Perfection of this dish is achieved thanks to onion roasted to a golden colour. Roasted duck with red and white wine cabbage, potato dumplings and fried onion - Delicacy of Czech villages served usually on the occasion of feasts and celebrations. -

Cuisine of the Wallachian Kingdom,The

Cuisine of the Wallachian Kingdom Wallachian Kingdom is a soubriquet for the Wallachian region in the eastern part of Moravia. This region is known for its beautiful hilly landscape, its folk architecture and mainly for its famous fruit cakes. Welcome to the plumdom If there is an ingredient which could be considered universal for this region, it would most definitely be the plum. If you provide a local with sufficient amount of plums, he will prepare any meal from starters to desserts. And after he is finished, he would probably distil some slivovitz (slivovice). Plums are the most plentiful fruit of the Wallachian region. It is no wonder then that our forefathers learned to make the best of it. Apart from the famous plum frgáls, which became a cultural heritage protected by the European Union quite recently, you can taste various plum sauces, plum butter, delicious dumplings with plum filling, baked plums in bacon and so on, but also, of course, thetraditional Moravian spirit called slivovice (slíva is one of the Czech words for a plum). Another typical representative of local cuisine is the traditional Wallachian cabbage soup called kyselica. The name is derived from the word kyselý which is the Czech for sour. Cabbage can be found across the whole area of Czech Republic and is one of the most important ingredients which, together with potatoes, is also a necessary ingredient for preparing really good kyselica. This soup is so popular among housewives and cooks that there are competitions for the best kyselica in the region and it has been awarded as the best traditional dish of all Wallachia. -

St. Petersburg

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels St. Petersburg April - May 2014 Stepping out Enjoy the good weather by exploring Smolny Noble atmosphere History and style. Dining at the Palkin inyourpocket.com N°94 Contents Where to eat 21 ESSENTIAL Rubinshteina Street 36 CIT Y GUIDES Restaurants in Hotels 38 Nightlife 42 Foreword 4 What to see 46 In the News 5 The Essentials 46 Peterhof 50 Arrival & Getting Around 6 Where to stay 52 City Basics 8 Interview with consierge 54 Language 9 Shopping 56 Culture & Events 10 Expat & Lifestyle 58 Concerts, festivals and exhibitions 10 The Expat Experience 59 Sport news 15 Business 60 Features 16 Smolny District 16 Maps & Index Palkin. Historic dining 19 Metro map 61 Nevsky prospect 40 City map 62 Street register 64 www.facebook.com/StPetersburgYourPocket Moscow 65 www.facebook.com/StPetersburgInYourPocket April - May 2014 3 Foreword In the News Spring has sprung and St. Petersburg is getting a new look! After months of long, dark nights it’s lovely to feel some sun ECONOMIC FORUM BOLSHOI DRAMA THEATRE on your skin and enjoy warm days that are getting longer The St. Petersburg International Economic Forum will be and longer. It is a real pleasure going into the centre after held on 22-14 May this year. The forum is the main an- Tovstonogov Bolshoi Drama Theater on the Fontanka work, walking along the crowded Nevsky while it’s still light nual international economic and business forum convened Embankment will be reopened on May 27. The thea- St. Petersburg In YourESSENTIAL Pocket and seeing people enjoying late night dinners and drinks in Russia. -

Typical Czech Cuisine

Typical Czech Cuisine Czech cuisine is famous for its varieties of meat, which plays the main role on a plate, and further for the variety of delicious sauces, dumplings and soups. Local tastes As in every country, the traditional cuisine of the Czech Republic is given by its location, its climate and crops which find favourable conditions in this area. It is no wonder then that in this moderate climate with large water areas, many rivers and forests the typical meals consist of field crops, vegetables and game. The Czech cuisine is also rich in mushrooms, for the Czechs are quite keen mushroom pickers and the climate in this country, as well as in the most Central Europe, is just perfect for growth of mushrooms. When it comes to desserts then, the Czech land is rich in many kinds of pulp fruit and berries used in cakes together with curd cheese, walnut and poppy seed. One of the main characteristics of Czech cuisine is that the meal usually consists of a soup and a main course. The soup has quite often a form of broth with various ingredients, mostly vegetables according to the season, and pastinas. Thickened soups are also very common and traditional way of preparation. As a thickener the Czechs usually use roux of flour and the most typical ingredients are legumes, sausages or giblets. This kind of soup can be served as a main course with bread. Traditional soups include for example the potato soup, bean soup, lentil soup, cabbage soup, mushroom soup, fish soup – which many households hold for theirtraditional Christmas soup, and so on. -

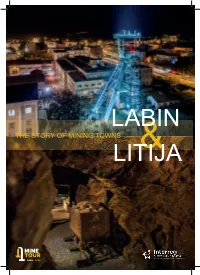

LABIN LITIJA Invites You to Learn

LABIN THE STORY OF MINING TOWNS LITIJA& MINE TOUR LITIJA 194 km LABIN The rich mining heritage of Labin and Litija can be learned about through an extensive collection of mining items, geological and mining maps, written documentation, old postcards, photographs and archival lms showing the development of mining in both cities. In Labin, actors will take you back in time. Through the stories of miners, you will get to know their way of life and the historical facts that inuenced the creation of this mining town. In Litija, you will enter the Sitarjevec mine accompanied by a guide, discover the secrets of the underground world and get to know the mine and the work of miners in an authentic environment. Discover MINE TOUR: www.mine-tour.eu minetourproject Mobile applications minetour.app LABIN invites you to learn In the eastern part of Istria, at a distance of only three kilometres from the sea, lies the medieval town of Labin. It is a town of rich cultural and historical heritage and a unique combination of natural beauty for an active holiday with magnicent gastronomic symphonies provided by numerous local restaurants and taverns. The city is divided into two parts: the old and the new part. The old part of town is located on a hill situated at 320 m above sea level and with a very picturesque appearance. The new part, located at the foot of the hill, is of interesting architecture created as a reection of centuries of mining. Doors of St. Flora represent the entrance to the Old Town and the inspiring story of the place, its historical and cultural tradition.