The Chesapeake Bay Pilots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Room, Buy Your Monthly Commuting Pass, Donate to Your Favorite Charity…Whatever Moves You Most

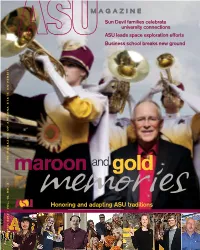

Sun Devil families celebrate university connections ASU leads space exploration efforts Business school breaks new ground THEMAGAZINEOFARIZONASTATEUNIVERSITYmaroon and gold memoriesHonoring and adapting ASU traditions MARCH 2012 | VOL. 15, NO. 3 IMAGINE WHAT YOU COULD DO WITH YOUR SPECIAL SAVINGS ON AUTO INSURANCE. Upgrade to an ocean view room, buy your monthly commuting pass, donate to your favorite charity…whatever moves you most. As an ASU alum, you could save up to $343.90 safer, more secure lives for more than 95 years. Responsibility. What’s your policy? CONTACT US TODAY TO START SAVING CALL 1-888-674-5644 Client #9697 CLICK LibertyMutual.com/asualumni AUTO COME IN to your local offi ce This organization receives fi nancial support for allowing Liberty Mutual to offer this auto and home insurance program. *Discounts are available where state laws and regulations allow, and may vary by state. To the extent permitted by law, applicants are individually underwritten; not all applicants may qualify. Savings fi gure based on a February 2011 sample of auto policyholder savings when comparing their former premium with those of Liberty Mutual’s group auto and home program. Individual premiums and savings will vary. Coverage provided and underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance Company and its affi liates, 175 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA. © 2011 Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. All rights reserved. The official publication of Arizona State University Vol. 15, No. 3 Scan this QR code President’s Letter to view the digital magazine Of all the roles that the ASU Alumni Association plays as an organization, perhaps none is more important than that PUBLISHER Christine K. -

Benny Ambrose: Life

BENNY AMBROSE: LIFE hen Benny Ambrose ran away from in 1917 when the United States entered World his northeastern Iowa farm home War I, and he promptly enlisted.3 W near Amana at the age of 14, there Ambrose was assigned to the famed Rainbow was little to predict that he would become a leg Division, which served on the front lines in endary figure in Minnesota's north woods. Yet, a France. In later years he never talked about his chance encounter brought him there, and for overseas experiences except to tell about an more than 60 years he lived in the lake countr)' Ojibway army buddy from Grand Portage. This along the United States-Canadian border subsist man kindled Ambrose's dreams by describing a ing by prospecting, trapping, guiding, and garden vast and beautiful timbered wilderness filled with ing. After his death in 1982, he was honored with lakes and rivers in northeastern Minnesota, where commemorative markers on each side of the gold and sUver were waiting to be discovered. He international border two nations' tributes to the decided to prospect there for a year or two to person reputed to be the north countr)''s most raise the money needed to go on to Alaska.4 self-sufficient woodsman. 1 Soon after his military discharge in 1919, Benjamin Quentin Ambrose was born in Ambrose headed for Hovland at the northeastern about 1896. Little is known about his early years tip of Minnesota. At that time The America, a up to the fateful clay in 1910 when he ran away. -

Understanding Pilotage Regulation in the United States

Unique Institutions, Indispensable Cogs, and Hoary Figures: Understanding Pilotage Regulation in the United States BY PAUL G. KIRCHNER* AND CLAYTON L. DIAMOND** I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 168 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND................................................................... 171 A. Congress Creates the State Pilotage System .............................. 171 B. Congress Places Restrictions on State Regulation and Establishes Federal Requirements for Certain Vessels ........... 176 1. Federal Pilotage of Coastwise Steam Vessels .................... 176 2. Pilotage System for Ocean-going Vessels on the Great Lakes .................................................................................. 179 III. CURRENT STATUTORY SCHEME: CHAPTER 85 OF TITLE 46, U.S. CODE ............................................................................................... 181 IV. THE STATE PILOTAGE SYSTEM ............................................................ 187 V. FEDERAL REGULATION OF PILOTAGE .................................................. 195 VI. OVERLAP BETWEEN STATE AND FEDERAL SYSTEMS: ADMINISTRATIVE RESPONSES TO MARINE CASUALTIES. .......................... 199 VII. CONCLUSION ...................................................................................... 204 I. INTRODUCTION Whether described as ―indispensable cogs in the transportation system of every maritime economy‖1 or as ―hoary figure[s]‖,2 pilots have one of * Paul G. Kirchner is the Executive -

English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records

T iPlCTP \jrIRG by Lot L I B RAHY OF THL UN IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS 975.5 D4-5"e ILL. HJST. survey Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/englishduplicateOOdesc English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records compiled by Louis des Cognets, Jr. © 1958, Louis des Cognets, Jr. P.O. Box 163 Princeton, New Jersey This book is dedicated to my grandmother ANNA RUSSELL des COGNETS in memory of the many years she spent writing two genealogies about her Virginia ancestors \ i FOREWORD This book was compiled from material found in the Public Record Office during the summer of 1957. Original reports sent to the Colonial Office from Virginia were first microfilmed, and then transcribed for publication. Some of the penmanship of the early part of the 18th Century was like copper plate, but some was very hard to decipher, and where the same name was often spelled in two different ways on the same page, the task was all the more difficult. May the various lists of pioneer Virginians contained herein aid both genealogists, students of colonial history, and those who make a study of the evolution of names. In this event a part of my debt to other abstracters and compilers will have been paid. Thanks are due the Staff at the Public Record Office for many heavy volumes carried to my desk, and for friendly assistance. Mrs. William Dabney Duke furnished valuable advice based upon her considerable experience in Virginia research. Mrs .Olive Sheridan being acquainted with old English names was especially suited to the secretarial duties she faithfully performed. -

Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve - Virginia

COMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve - Virginia Prepared by: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage Natural Heritage Technical Report 05-04 2005 Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 i Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve -Virginia 2005 Natural Heritage Technical Report 05-04 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage 217 Governor Street Richmond, Virginia 23219 (804) 786-7951 This document may be cited as follows: Erdle, S. Y. and K. E. Heffernan. 2005. Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve-Virginia. Natural Heritage Technical Report #05- 04. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage. Richmond, Virginia. 35 pp. plus appendices. ii Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 iii Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ iv PLAN SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 -

Chapter Four

Chapter Four Translating lndustr~l7ansfortning Science: Making a Transition in Virginia, 1963- 1976 From 1963 to 1976, science "took off" in Virginia, as the business community slowly gained an awareness of the valuable contributions made to industry by organized scientists. Often assuming center stage in research and development, Virginia scientists rose in stature, both professionally and socially. Increasingly, scientists were called in to lend their expert knowledge, offering various explanations for events as well as providing mechanisms by which social groups - especially politi- cal - could accomplish objectives they viewed as necessary. At first, the Virginia Academy of Science benefited from the new role of scien- tists, achieving a fairly strong position in many of the webs of negotia- tions defining the course of Virginia science. Most notably, the Acad- emy was able to translate political interest in research and develop- ment into political interest in science education. This initial success did not last, however, in large past due to the inability of the VAS to con- tinue to position itself in terms of the changing context of scientific professionalism. Setting the Stage: Virginia, 1963- 1976 By the mid-sixties, Virginia at last could breathe a small sigh of relief. Massive Resistance -which many Virginia historians cite as the most crucial, shaping event of the century in the Commonwealtl~- by and large had come to an end, and the Old Dominion had begun the slow journey an7ayfrom the evil of racism towards a more moderate -

The Thomas Chew Family of Orange County and the Colonial Virginia Recessional

Courses of Empire: The Thomas Chew Family of Orange County and the Colonial Virginia Recessional by Frederick Madison Smith, Secretary, NSMFD Despite the burgeoning prosperity of his young family in the emerging Virginia Piedmont, Ambrose Madison’s murder in the summer of 1732 left his widow Frances Tayl or Madison and his children in a somewhat precarious position legally and financially. Having divested himself of his holdings in the Ti dewater, Ambrose’s “Mount Pleasant” estate was his chief capital holding and income source. However, this planta tion, a joint patent to Ambrose and his brother-in-law Thomas Chew, husband of his wife’s younger and nearest- in-age sister Martha Taylor, had never been formally divided between them and, on Ambrose’s death, titl e to the 4,675 acre tract passed entirely to Chew. Whatever anxieties, if any, attended this legal fact for Frances Taylor Madison, they were resolved on May 26, 1737 when Chew deeded 2,850 acres of the original pa tent “to Frances Maddison, widow and James Maddison, son and heir of Ambrose Madison, deceased.” This deed, recorded in the Orange Coun ty Virginia Deed Book 2, pages 10-13, further recites that “Ambrose Maddison depart ed this life before any legal division of the land was made, by which the whole was vested in Thomas Chew as survivor.” Mirroring the provisions of Ambrose’s will, Chew’s deed gave Frances a life estate only with the ti tle passing unencumbered on her death to her son, James Madison Sr., the President’s father. -

Vi Rt Ual April 30, 2021

OFFICE OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH VI RT UAL APRIL 30, 2021 RESEARCH.UN D ERG RAD UATE. VT.ED UI SYMPOSIUM Contents WELCOME FROM ASSOCIATE VICE PROVOST FOR UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION, DR. JILL SIBLE 2 WELCOME FROM DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, KERI SWABY 3 ACC MEETING OF THE MINDS - RECOGNITION 4 NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH - RECOGNITION 5 TRAVEL AWARDS - RECOGNITION 6 2021 OUTSTANDING UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH MENTOR AWARDS 7 OFFICE OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH AMBASSADORS 8 INFORMATIONAL BOOTHS 9 ABSTRACTS (ALPHABETICAL) 10 1 Jill C. Sible, Ph.D. Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, Professor of Biological Sciences Welcome Welcome to Virginia Tech’s Spring Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship Virtual Symposium. This event is a celebration of the creative and scholarly accomplishments of undergraduate students campus- wide. Our program reflects the quality and diversity of undergraduate research at Virginia Tech. Many of the projects are the result of collaborations among several students. Undergraduate research is recognized as one of the high impact practices in undergraduate education. Students who participate in undergraduate research are more likely to thrive and persist in their education. They become co-creators of knowledge, makers of objects that are useful and beautiful. At the heart and soul of these projects are collaborations between undergraduates and their mentors. Many thanks to the faculty, graduate students and others who commit to these scholarly endeavors with undergraduate students. It is remarkable that we have near-record levels of presentations by students despite the challenges of conducting and presenting undergraduate research during a pandemic. This is credit to our amazing students and dedicated faculty and the resourcefulness of the Office of Undergraduate Research in creating the virtual symposium. -

Sandy Hook to Cape Henry

19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 3 ¢ 169 Sandy Hook to Cape Henry (1) Between New York Bay and Delaware Bay is the (9) New Jersey coast with its many resorts, its inlets and its Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System (CBIBS) Intracoastal Waterway. Delaware Bay is the approach to (10) The Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System Wilmington, Chester, Philadelphia, Camden and Trenton; (CBIBS) is a network of data-sensing buoys along the below Wilmington is the Delaware River entrance to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, the deep inside link The buoys broadcast real-time weather/environmental between Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. The Delaware- data and voice narration of natural and cultural history Maryland-Virginia coast has relatively few resorts; the of the area. Real-time information from the buoy can numerous inlets are backed by a shallow inside passage be retrieved by phone at 877–BUOY–BAY or at www. that extends all the way from Delaware Bay to Chesapeake buoybay.noaa.gov. Bay. The last seven chapters, nearly half of this book, (11) are required to describe Chesapeake Bay to Norfolk and Radar Newport News, to Washington and Baltimore and to (12) Radar, though always a valuable navigational aid, Susquehanna River 170 miles north of the Virginia Capes. is generally of less assistance in navigation along this (2) A vessel approaching this coast from seaward will coast due to the relatively low relief; the accuracy of radar be made aware of its nearness by the number of vessels ranges to the beach cannot be relied upon. -

The Newsletter of the American Pilots' Association

The Newsletter of the American Pilots’ Association September 10, 2018 Page 1 APA AND VIRGINIA PILOTS PHOTOS OF CHAIRMAN SUMWALT’S VISIT CONTINUE OUTREACH TO NTSB WITH THE VIRGINIA PILOTS 1. Chairman Sumwalt and Captain Jay Saunders (Virginia Pilot Asso- On July 31st and August 1st, the Virginia Pilot ciation) board the M/V ZIM LUANDA. 2. Captain Whiting Chisman, Association (VPA) hosted National Transportation Virginia Pilot Association Vice President (right), discusses pilotage Safety Board (NTSB) Chairman, the Honorable Rob- with Chairman Sumwalt. 3. Captain Saunders gives Chairman Sumwalt an overview of the pilotage assignment. 4. From left to ert L. Sumwalt, along with Mr. Michael Hughes (a right: Captain Jorge Viso (APA President), Chairman Sumwalt, and senior NTSB communications official) at their Vir- Michael Hughes (NTSB). 5. Captain Bill Cofer, Virginia Pilot Asso- ginia Beach offices. APA President, Captain Jorge ciation President (center), briefs Chairman Sumwalt on the Virginia Viso, also participated in this meeting. pilotage area, as Captain Viso observes. In addition to receiving briefings and a tour of 1 2 the VPA facilities, Chairman Sumwalt also observed a pilotage assignment firsthand. Chairman Sumwalt was first appointed to the NTSB in 2006 and has since been reappointed twice. He was sworn in as the 14th Chairman of the NTSB in August 2017. He previously served as Vice Chairman of the NTSB. Captain Bill Cofer, VPA President, began the Chairman’s visit by giving him an overview of the Virginia Pilots’ operation, as well as a comprehen- sive briefing on Virginia’s pilotage waters. Captain Cofer, Captain Whiting Chisman (VPA Vice Presi- 4 dent), and Captain Viso then gave a presentation on ultra large container vessels (ULCVs) and the chal- lenges associated with piloting these vessels. -

The Westervelt Family Compiled and Arranged by Her Husband During the Last Twenty Years of His Life, Very Great Pleasure to Undertake the Task Allotted to Him

GENEALOGY OF THE 1 \\ ESTERVELT FA11ILY CO'.IIPILED BY THE LATE WALTER TALLMAN WESTERVELT REVISED AND EDITED BY WHARTON DICKINSON NEW YORK PRESS OF TOBIAS A, WRIGHT 1905 ARMS OF Y.~~ \VESTERYELT As emblazoned upon the tomb, in the lioor of the nave of the Church, at Harderwyk, Holland. WESTERVELT ;\R~1s.-Yert, three flenr delis. or: crest, two arms in armor, argent; hands natural \ppr. 1 out of a ducal coronet holding a lieur de lis, or. FOREWORD No words more fully express the intent of this compilation, properly called Some Gleanings, Historic and Genealogical, than those voiced by the Psalmist, when he says: "Which we have heard and known and our fathers have told us * * * That the generations to come might know them, even the children which should be born ; who should arise and de clare them to their children." (Psalm lx:xviii.) Years ago the compiler came into the possession of some frag mentary notes, collected by one of his earlier ancestors, compris ing data relating to the numerous families who were identified with the history of Bergen County, N. J., in colonial days. Among these families was that of WESTERVIU,T, and after tracing his own line of descent through this and allied families, the work became so interesting that he was led to make further researches, to presenre at least an outline of the history of that family for this and future generations. It is a source of honest and commendable pride to an Amer ican, that his ancestors for many generations in this land have done their part as self-supporting citizens in their several periods, for their neighborhood, their colony, their State and their country; as well as a satisfaction to know that at the birth of the Republic, or in the period of its peril, they took a part in the making of this government and in establishing its independence. -

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Northeast Region Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2008/129 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Colonial National Historical Park ON THE COVER Upper left: Tidal Mesohaline and Polyhaline Marsh; photograph by Karen D. Patterson. Upper right: Tidal Bald Cypress Forest / Woodland. Lower left: Coastal Plain Loblolly Pine – Oak Forest. Lower right: Coastal Plain / Piedmont Floodplain Swamp Forest (Green Ash – Red Maple Type). Photographs by Gary P. Fleming. 2 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Colonial National Historical Park Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2008/129 Karen D. Patterson Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage 217 Governor Street, 3rd Floor Richmond, VA 23219 June 2008 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 3 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Colonial National Historical Park The Northeast Region of the National Park Service (NPS) comprises national parks and related areas in 13 New England and mid-Atlantic states. The diversity of parks and their resources are reflected in their designations as national parks, seashores, historic sites, recreation areas, military parks, monuments and memorials, and rivers and trails. Biological, physical, and social science research results, natural resource inventory and monitoring data, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences related to these park units are disseminated through the NPS/NER Technical Report (NRTR) and Natural Resources Report (NRR) series. The reports are a continuation of series with previous acronyms of NPS/PHSO, NPS/MAR, NPS/BSO-RNR, and NPS/NERBOST.