Understanding Pilotage Regulation in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travels in America Performed in 1806, for the Purpose of Exploring

Library of Congress Travels in America performed in 1806, for the purpose of exploring the rivers Alleghany, Monongahela, Ohio, and Mississippi, and ascertaining the produce and condition of their banks and vicinity. By Thomas Ashe, esq. ... TRAVELS IN AMERICA, PERFORMED IN 1806, For the Purpose of exploring the RIVERS ALLEGHANY, MONONGAHELA, OHIO, AND MISSISSIPPI, AND ASCERTAINING THE PRODUCE AND CONDITION OF THEIR BANKS AND VICINITY. BY THOMAS ASHE, ESQ. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. 1. LC LONDON: PRINTED FOR RICHARD PHILLIPS, BRIDGE-STREET; By John Abraham, Clement's Lane. 1808. F333 A8 224612 15 PREFACE. Travels in America performed in 1806, for the purpose of exploring the rivers Alleghany, Monongahela, Ohio, and Mississippi, and ascertaining the produce and condition of their banks and vicinity. By Thomas Ashe, esq. ... http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.3028a Library of Congress IT is universally acknowledged, that no description of writing comprehends so much amusement and entertainment as well written accounts of voyages and travels, especially in countries little known. If the voyages of a Cook and his followers, exploratory of the South Sea Islands, and the travels of a Bruce, or a Park, in the interior regions of Africa, have merited and obtained celebrity, the work now presented to the public cannot but claim a similar merit. The western part of America, become interesting in every point of view, has been little known, and misrepresented by the few writers on the subject, led by motives of interest or traffic, and has not heretofore been exhibited in a satisfactory manner. Mr. Ashe, the author of the present work, and who has now returned to America, here gives an account every way satisfactory. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

View Room, Buy Your Monthly Commuting Pass, Donate to Your Favorite Charity…Whatever Moves You Most

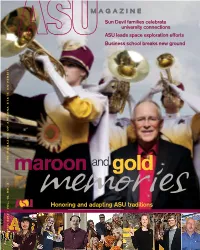

Sun Devil families celebrate university connections ASU leads space exploration efforts Business school breaks new ground THEMAGAZINEOFARIZONASTATEUNIVERSITYmaroon and gold memoriesHonoring and adapting ASU traditions MARCH 2012 | VOL. 15, NO. 3 IMAGINE WHAT YOU COULD DO WITH YOUR SPECIAL SAVINGS ON AUTO INSURANCE. Upgrade to an ocean view room, buy your monthly commuting pass, donate to your favorite charity…whatever moves you most. As an ASU alum, you could save up to $343.90 safer, more secure lives for more than 95 years. Responsibility. What’s your policy? CONTACT US TODAY TO START SAVING CALL 1-888-674-5644 Client #9697 CLICK LibertyMutual.com/asualumni AUTO COME IN to your local offi ce This organization receives fi nancial support for allowing Liberty Mutual to offer this auto and home insurance program. *Discounts are available where state laws and regulations allow, and may vary by state. To the extent permitted by law, applicants are individually underwritten; not all applicants may qualify. Savings fi gure based on a February 2011 sample of auto policyholder savings when comparing their former premium with those of Liberty Mutual’s group auto and home program. Individual premiums and savings will vary. Coverage provided and underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance Company and its affi liates, 175 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA. © 2011 Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. All rights reserved. The official publication of Arizona State University Vol. 15, No. 3 Scan this QR code President’s Letter to view the digital magazine Of all the roles that the ASU Alumni Association plays as an organization, perhaps none is more important than that PUBLISHER Christine K. -

Newsletter 3-1-2016

The Newsletter of the American Pilots’ Association March 1, 2016 Page 1 (NAVTECH) will meet on Wednesday afternoon. In addition to discussing the latest issues in electronic navigation practice and equipment, plans are under way to have NAVTECH members hear from various While many pilots government officials with responsibilities for naviga- around the country are tion programs. dealing with the chills The Suppliers’ Exhibition, an excellent oppor- of winter, a warm is- tunity to meet with maritime and pilotage related land breeze is on the vendors to discuss their products, will be held on way. Plans are well Wednesday and Thursday. underway for the 2016 As always, several social events will be held Biennial Convention, which is being held from Octo- during the week, including a Welcome Reception on ber 24-28 at the beautiful Fairmont Kea Lani Hotel Monday, a traditional luau on Wednesday, and a and Resort in Maui. The Convention is an un- closing Gala on Friday. matched opportunity for the Nation’s pilots to gather, To make attendance arrangements, go to share ideas and strengthen the pilotage system in the www.americanpilots.org and click “2016 APA U.S. This year’s Convention is hosted by the nine Convention.” There, pilots and other attendees can pilot associations in the Pacific Coast States: Alaska book flights, make hotel reservations, and register Marine Pilots, Columbia River Pilots, Columbia Riv- for the Convention. Pilots can also view the Exhibi- er Bar Pilots, Coos Bay Pilots, Hawaii Pilots, Puget tor Directory by clicking on “Exhibitor Registration” Sound Pilots, San Francisco Bar Pilots, Southeast and dragging the mouse over the booth diagrams. -

Mctolber-November 1982

mctolber- November 1982 Editor's Note: The effect of change on people and na tions is commonly accepted fact. Pursuing ways to predict, cause, deter, accommo date or confront change and its conse quences is how most of us spend our lives. Dealing with change is rarely easy, con venient or painless; and as Henry Steele Commager notes, "Change does not necessarily assure progress but progress implacably requires change. " It is from such viewpoint that this issue looks at change and the portent of change on this nation, its maritime Industry - in cluding seafarers, and the Seamen's Church Institute - past, present and future. From seafarer, maritime executive and artist to Institute board manager, Oxford don and poet, we think you will find their observations and concerns about change provocative and challenging ones. We would also like to know your reactions to this issue. Carlyle Windley Editor 1:00KOUT Volume 74 Number 3 October-November 1982 © 1982 Seamen's Church In stitute of New York an d New Jersey In Search of a Miracle American seamen speak out on the future of the nation's 2 merchant marine and their chances as professional seamen . America's Future: A View from Abroad Highlights from an intensive study by Oxford dons of the 5 technological , socio-economic and political forces changing America and the American Dream. The Sandy Hook Pilots A close-up look at one of the Port's most esteemed but 10 little known associations. The Era of the Floating Chapels The origin of the floating church for seafarers and the, role of the floating chapel in the history of the 29 Institute and the Port of New York . -

Midtemperature Solar Systems Test Facility Predictions for Thermal Performance Based on Test Data

Midtemperature Solar Systems Test Facility Predictions for Thermal Performance Based on Test Data Solar Kinetics T -700 Solar Collector With Glass Reflector Surface Thomas D. Harrison DISmtBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IS UNUMIT£0 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency Thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their emplo.yees, makes any warranty, express or implied or assumes any le~al liability or responsibihty for the accuracy, completeness, or usefUlness of any informat10n, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. -

Fannie Mae Proposed Underserved Markets Plan

Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan For the Manufactured Housing, Affordable Housing Preservation, and Rural Housing Markets May 8, 2017 5.8.2017 1 of 239 Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. Disclaimer Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. 5.8.2017 2 of 239 Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. Table of Contents I. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................... 10 II. Introduction to the Duty to Serve Plans ........................................................................................................................ -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Ten Commandments: Foundation of American Society

Thank you for choosing this resource. Our booklets are designed for grassroots activists and concerned citizens—in other words, people who want to make a difference in their families, in their communities, and in their culture. History has clearly shown the influence that the “Values Voter” can have in the political process. FRC is committed to enabling and motivating individuals to bring about even more positive change in our nation and around the world. I invite you to use this pamphlet as a resource for educating yourself and others about some of the most pressing issues of our day. FRC has a wide range of papers and publications. To learn more about other FRC publications and to find out more about our work, visit our website at www.frc.org or call 1-800-225-4008. I look forward to working with you as we bring about a society that respects life, protects marriage, and defends religious liberty. President Family Research Council Ten Commandments: Foundation of American Society by Dr. Kenyn Cureton For a majority of Americans, the Ten Commandments are not set in stone. According to a USA Today poll, “Sixty percent of Americans cannot name five of the Ten Commandments.”1 In fact, it is amazing what Americans do know by comparison: 74% of Americans can name all three Stooges – Moe, Larry, and Curley.2 35% of Americans can recall all six kids from the Brady Bunch.3 25% of Americans can name all seven ingredients of McDonald’s Big Mac®.4 Here is the sad news: Only 14% can accurately name all Ten Commandments.5 Yet 78% of Americans are in favor of public displays of the Commandments.6 How ironic. -

Benny Ambrose: Life

BENNY AMBROSE: LIFE hen Benny Ambrose ran away from in 1917 when the United States entered World his northeastern Iowa farm home War I, and he promptly enlisted.3 W near Amana at the age of 14, there Ambrose was assigned to the famed Rainbow was little to predict that he would become a leg Division, which served on the front lines in endary figure in Minnesota's north woods. Yet, a France. In later years he never talked about his chance encounter brought him there, and for overseas experiences except to tell about an more than 60 years he lived in the lake countr)' Ojibway army buddy from Grand Portage. This along the United States-Canadian border subsist man kindled Ambrose's dreams by describing a ing by prospecting, trapping, guiding, and garden vast and beautiful timbered wilderness filled with ing. After his death in 1982, he was honored with lakes and rivers in northeastern Minnesota, where commemorative markers on each side of the gold and sUver were waiting to be discovered. He international border two nations' tributes to the decided to prospect there for a year or two to person reputed to be the north countr)''s most raise the money needed to go on to Alaska.4 self-sufficient woodsman. 1 Soon after his military discharge in 1919, Benjamin Quentin Ambrose was born in Ambrose headed for Hovland at the northeastern about 1896. Little is known about his early years tip of Minnesota. At that time The America, a up to the fateful clay in 1910 when he ran away. -

Hon. Patrick J. Leahy Chairman, U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary 433 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, D.C

Hon. Patrick J. Leahy Chairman, U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary 433 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Hon. Jefferson B. Sessions Ranking Member, U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary 335 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Chairman Leahy and Ranking Member Sessions: We the undersigned professors of law write in support of the confirmation of Judge Sonia Sotomayor as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. As a federal judge at both the trial and appellate levels, Judge Sotomayor has distinguished herself as a brilliant, careful, fair-minded jurist whose rulings exhibit unfailing adherence to the rule of law. Her opinions reflect careful attention to the facts of each case and a reading of the law that demonstrates fidelity to the text of statutes and the Constitution. She pays close attention to precedent and has proper respect for the role of courts and the other branches of government in our society. She has not been reluctant to protect core constitutional values and has shown a commitment to providing equal justice for all who come before her. Judge Sotomayor’s stellar academic record at Princeton and Yale Law School is testament to her intellect and hard work, and is especially impressive in light of her rise from modest circumstances. That she went on to serve as an Assistant District Attorney for New York County speaks volumes about her strength of character and commitment to the rule of law. When in private practice as a corporate litigator in New York, she was deeply engaged in public activities, including service on the New York Mortgage Agency and the New York City Campaign Finance Board, as well as serving on the Board of Directors of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund.