Washington State Pilotage Final Report and Recommendations Washington State Joint Transportation Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Merchant Marine

“China’s Merchant Marine” A paper for the China as “Maritime Power” Conference July 28-29, 2015 CNA Conference Facility Arlington, Virginia by Dennis J. Blasko1 Introductory Note: The Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook defines “merchant marine” as “all ships engaged in the carriage of goods; or all commercial vessels (as opposed to all nonmilitary ships), which excludes tugs, fishing vessels, offshore oil rigs, etc.”2 At the end of 2014, the world’s merchant ship fleet consisted of over 89,000 ships.3 According to the BBC: Under international law, every merchant ship must be registered with a country, known as its flag state. That country has jurisdiction over the vessel and is responsible for inspecting that it is safe to sail and to check on the crew’s working conditions. Open registries, sometimes referred to pejoratively as flags of convenience, have been contentious from the start.4 1 Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), a Senior Research Fellow with CNA’s China Studies division, is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today (Routledge, 2006).The author wishes to express his sincere thanks and appreciation to Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, U.S. Navy (Ret), for his guidance and patience in the preparation and presentation of this paper. 2 Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: Merchant Marine,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2108.html. According to the Factbook, “DWT or dead weight tonnage is the total weight of cargo, plus bunkers, stores, etc., that a ship can carry when immersed to the appropriate load line. -

Service Operations Vessel 9020 Standard

1. Click with cursor in the blank space above 2. Drag & Drop Picture (16:9 ratio) 3. Optional: add hyperlink to Damen.com product page to the picture SERVICE OPERATIONS VESSEL 9020 STANDARD PICTURE OF SIMILAR VESSEL GENERAL DECK LAY-OUT Basic functions To provide stepless access onto Lift 2 tonne lift connecting 4 access levels (option: 6) for continuous windfarm assets for technicians, tools access between warehouse, weather deck and WTG via optional and parts by access system, crane and gangway. daughter craft. in both Construction Pedestals - for optional crane Support and Service Operations. - for optional gangway system Classification DNV-GL Maritime, notation: Helicopter winch area on foreship, stepless access to warehouse, hospital. Option: X 1A1, Offshore Service Vessel, helideck D-size 21m COMF(C-3, V-3), DYNPOS(AUTR), CTV landing facilities 1 fixed steel landing at stern. Clean, SF, E0, DK(+), SPS, NAUT(OSV- 1 removable alum. landing SB / PS. A), BWM(T), Recyclable, Crane Flag ACCOMMODATION Owner Crew/ special personnel 15-20x crew, 40-45x SP, all single cabins provided with WiFi, LAN, telephone and audio / video entert. (VOD and sat. TV). DIMENSIONS Other facilities up to 6 Offices and 5 meeting/ conference rooms for Charterer’s Length overall 89.65 m use. Beam moulded 20.00 m 2 Recr.-dayrooms, reception, hospital, drying rooms (M/F), Depth moulded 8.00 m changing rooms (M/F), wellness area (gym and sauna). Draught base (u.s. keel) 4.80 (6.30) m Gross Tonnage 6100 GT NAUTICAL AND COMMUNICATION EQUIPMENT Nautical Radar X-band + S-band, ECDIS, Conning, GMDSS Area 1, 2 and CAPACITIES 3. -

View Room, Buy Your Monthly Commuting Pass, Donate to Your Favorite Charity…Whatever Moves You Most

Sun Devil families celebrate university connections ASU leads space exploration efforts Business school breaks new ground THEMAGAZINEOFARIZONASTATEUNIVERSITYmaroon and gold memoriesHonoring and adapting ASU traditions MARCH 2012 | VOL. 15, NO. 3 IMAGINE WHAT YOU COULD DO WITH YOUR SPECIAL SAVINGS ON AUTO INSURANCE. Upgrade to an ocean view room, buy your monthly commuting pass, donate to your favorite charity…whatever moves you most. As an ASU alum, you could save up to $343.90 safer, more secure lives for more than 95 years. Responsibility. What’s your policy? CONTACT US TODAY TO START SAVING CALL 1-888-674-5644 Client #9697 CLICK LibertyMutual.com/asualumni AUTO COME IN to your local offi ce This organization receives fi nancial support for allowing Liberty Mutual to offer this auto and home insurance program. *Discounts are available where state laws and regulations allow, and may vary by state. To the extent permitted by law, applicants are individually underwritten; not all applicants may qualify. Savings fi gure based on a February 2011 sample of auto policyholder savings when comparing their former premium with those of Liberty Mutual’s group auto and home program. Individual premiums and savings will vary. Coverage provided and underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance Company and its affi liates, 175 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA. © 2011 Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. All rights reserved. The official publication of Arizona State University Vol. 15, No. 3 Scan this QR code President’s Letter to view the digital magazine Of all the roles that the ASU Alumni Association plays as an organization, perhaps none is more important than that PUBLISHER Christine K. -

MN 20 of 2018 New Building Procedures – Ships and Boats

South African Maritime Safety Authority Ref: SM6/5/2/1 Date: 7 June 2018 Marine Notice No. 20 of 2018 New Building Procedures – Ships and Boats TO SHIP/BOAT BUILDERS, NAVAL ARCHITECTS, VESSEL OWNERS, REGIONAL MANAGERS, PRINCIPAL OFFICERS, REGISTRAR OF SHIPS AND SURVEY STAFF. Summary The following marine notice provides guidance to industry on processes to be followed for plan approval and SAMSA attendance during a new building, of a ship or boat to achieve compliance with the Merchant Shipping Act 57 of 1951 and supporting regulations applicable to Non-SOLAS convention ships (class vessels) and boats (category vessels). 1. INTRODUCTION The Merchant Shipping Act and supporting regulations address vessel construction in a compliance based manner while the process of building a ship/boat is a dynamic one which requires evaluation of all elements and continuous confirmation that the changing of one or more parameters has not affected others negatively. The difference between the two approaches can be represented as follows: Regulatory Compliance-based Approach Ship/boat design process While the design process is meant to be completed before submission of plans to the Authority, it is important to realise that requirements for regulatory changes may affect other elements of the vessel design. It is accordingly important for SAMSA to play a timely role in the plan approval and survey process to avoid requirements for changes late in a project which may cause delays and additional costs or even affect the operational capability of the end product. It is also important for the owner/builder to understand the legislative framework in which he/she is working to allow SAMSA the opportunity to identify area’s of non-compliance at an early stage for the same reasons as those outlined above. -

Newsletter 3-1-2016

The Newsletter of the American Pilots’ Association March 1, 2016 Page 1 (NAVTECH) will meet on Wednesday afternoon. In addition to discussing the latest issues in electronic navigation practice and equipment, plans are under way to have NAVTECH members hear from various While many pilots government officials with responsibilities for naviga- around the country are tion programs. dealing with the chills The Suppliers’ Exhibition, an excellent oppor- of winter, a warm is- tunity to meet with maritime and pilotage related land breeze is on the vendors to discuss their products, will be held on way. Plans are well Wednesday and Thursday. underway for the 2016 As always, several social events will be held Biennial Convention, which is being held from Octo- during the week, including a Welcome Reception on ber 24-28 at the beautiful Fairmont Kea Lani Hotel Monday, a traditional luau on Wednesday, and a and Resort in Maui. The Convention is an un- closing Gala on Friday. matched opportunity for the Nation’s pilots to gather, To make attendance arrangements, go to share ideas and strengthen the pilotage system in the www.americanpilots.org and click “2016 APA U.S. This year’s Convention is hosted by the nine Convention.” There, pilots and other attendees can pilot associations in the Pacific Coast States: Alaska book flights, make hotel reservations, and register Marine Pilots, Columbia River Pilots, Columbia Riv- for the Convention. Pilots can also view the Exhibi- er Bar Pilots, Coos Bay Pilots, Hawaii Pilots, Puget tor Directory by clicking on “Exhibitor Registration” Sound Pilots, San Francisco Bar Pilots, Southeast and dragging the mouse over the booth diagrams. -

Role-Based Bridge Organisation

New Organisation for Safe and Effective Operation of Cruise Ships Captain Hans Hederstrom, FNI John N Ritchie Introduction Traditionally ship’s bridges have been characterised by strong hierarchical organisations. The Captain’s arrival on the bridge would almost always mean their taking over the conning of the ship. That would also mean that all important decisions on heading and speed were based upon a plan which was only inside the Captain’s head. This environment turned the other Bridge Officers into passive bystanders and a team effort into a solo operation. We have also recently experienced a number of high profile accidents where the problems inherent in this type of environment have been highlighted. In the early 1990’s the industry saw the introduction of Bridge Resource Management (BRM) as a solution to stop accidents caused by single point failures, but this has not been the case. The BRM courses focused a lot of attention on developing assertiveness, encouraging Officers to speak up when a senior Officer deviated from the plan. It is easy to discuss about assertiveness in a classroom, and train in a simulator environment, but very hard to implement in real life - unless the Captain is proactively implementing a working environment where speaking up is not only accepted but encouraged. Even with a culture of challenge well established in an operational environment, there is another problem: if a junior Officer does not know what the operational limits of a route plan or berthing plan are, it’s difficult to challenge its execution. The trigger for a challenge should be based upon a perception that the person with the Conn has deviated either from the plan, or from the agreed limits of that plan. -

William Leggett: His Life, His Ideas, and His Political Role John J

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1964 William Leggett: his life, his ideas, and his political role John J. Fox Jr. Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fox, John J. Jr., "William Leggett: his life, his ideas, and his political role" (1964). Theses and Dissertations. 3199. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/3199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .o .. WILLIAM LEGGETT: HIS LIFE, HIS IDEAS AND HIS POLITICAL ROLE. ,. ·I:r, by John J. Fox, Jr. '" A THESIS Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts .. ·i: -.-:-;-:-·. .- . ' > Lehigh University 1964 ' . : \ ·,_,.: ,,' This thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ~2..z., 1,,9' Date j ff·· .-_ '. -... :.~,-,." .. -~,..· .. • ~: -7~' ' ' 7 I 71 ·,,, ~I } TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. The Formative Years, 1801-1826 ---------------------- l II. The Eventful Years, 1829-1839 ----------------------- 16 III. Equality for All------------------------------------ 29 IV. Civil Liberties------------------------------------- 47 v. Leggett and the Democratic Party-------------------- 63 .,, VI. Conclusion------------------------------------------ 84 ,, Footnotes------------------------------------------- 90 Bibliography---------------------------------------- 109 Vita ----------------------------------------------- 113 --'· I . ,,. I .,.I.. ,, William Leggett: His Life, His Ideas ,, And His Political Role. A Master's Thesis by John J. Fox, Jr. William Leggett.was born on April 30, 18010 The first eighteen years of his life were spent in New York City. -

Draft Final Report on Mtcp Tonnage Measurement Study

Tonnage Measurement Study MTCP Work Package 2.1 Quality and Efficiency Final Report Bremen /Brussels, November 2006 Disclaimer: The use of any knowledge, information or data contained in this document shall be at the user's sole risk. The members of the Maritime Transport Coordination Platform accepts no liability or responsibility, in negligence or otherwise, for any loss, damage or expense whatever sustained by any person as a result of the use, in any manner or form, of any knowledge, information or data contained in this document, or due to any inaccuracy, omission or error therein contained. The contents and the views expressed in the document remain the responsibility of the Maritime Transport Coordination Platform. The European Community shall not in any way be liable or responsible for the use of any such knowledge, information or data, or of the consequences thereof. Content 0. Executive Summary............................................................................................1 1 Introduction and Background ............................................................................2 2 Structure of Report..............................................................................................3 3. The London Tonnage Convention (1969) .......................................................4 3.1 Brief History..................................................................................................4 3.2 Purpose and Regulations of the Convention..................................................5 3.3 Definitions......................................................................................................8 -

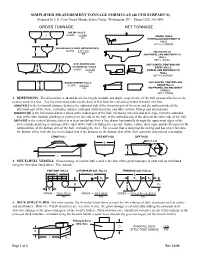

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Washington, DC Phone (202) 366-6441 GROSS TONNAGE NET TONNAGE SAILING HULLS D GROSS = 0.5 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = 0.9 GROSS SAILING HULLS (KEEL INCLUDED IN D) D GROSS = 0.375 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS SHIP-SHAPED AND SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND CYLINDRICAL HULLS D D BARGE HULLS GROSS = 0.67 LBD (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN 100 HULL) NET = 0.8 GROSS BARGE-SHAPED HULLS SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND D GROSS = 0.84 LBD BARGE HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS 1. DIMENSIONS. The dimensions, L, B and D, are the length, breadth and depth, respectively, of the hull measured in feet to the nearest tenth of a foot. See the conversion table on the back of this form for converting inches to tenths of a foot. LENGTH (L) is the horizontal distance between the outboard side of the foremost part of the stem and the outboard side of the aftermost part of the stern, excluding rudders, outboard motor brackets, and other similar fittings and attachments. BREADTH (B) is the horizontal distance taken at the widest part of the hull, excluding rub rails and deck caps, from the outboard side of the skin (outside planking or plating) on one side of the hull, to the outboard side of the skin on the other side of the hull. DEPTH (D) is the vertical distance taken at or near amidships from a line drawn horizontally through the uppermost edges of the skin (outside planking or plating) at the sides of the hull (excluding the cap rail, trunks, cabins, deck caps, and deckhouses) to the outboard face of the bottom skin of the hull, excluding the keel. -

IMPA Newsletter Issue 41 Web.Pdf

ISSUE NUMBER 41 / JANUARY 2017 THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MARITIME PILOTS’ ASSOCIATION IN THIS ISSUE: A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 1 A Message from the President Fellow Pilots, 3 Message from the From September 24 to 29, 2016, IMPA held its 23rd biennial Congress in Seoul, Korea. The Secretary General Congress was a great success and the excellent work done by the host committee needs to 4 Intoducing a new IMPA be underlined once more. Pilots from all over the world left Seoul not only with indelible Vice-President memories and a strong sense of comradeship, but also with the satisfaction that comes 5 Flooded ro-ro from having learned valuable lessons about their profession and the marine sector. written off 6 Answering the call – What struck me most, as it does each time I attend together, to share ideas, information and points of partnering with the the biennial meeting, is the tremendous amount of view, while at the same time providing them with Brisbane Marine Pilots information-sharing and problem-solving that goes the opportunity to enjoy each other’s company in a on not only through the formal agenda but in the convivial setting. 7 EU agreement on new many informal gatherings that take place along Ports Regulation the margins of the meeting itself. The wide range While the Congress was organized by pilots, it is 8 Pilot’s Pocket Guide review of discussions, both at the technical and the policy noteworthy that participation at the event also level, leads to the identification of best practices included persons from the entire spectrum of the Captain G A Coates and fosters a culture of innovation and continuous marine transportation sector. -

A Study of the Size of Nuclear Fuel Carriers, the Most Required Ships for Safety : How Large Can Ship's Tonnage Be? Azusa Fukasawa World Maritime University

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2013 A study of the size of nuclear fuel carriers, the most required ships for safety : how large can ship's tonnage be? Azusa Fukasawa World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Risk Analysis Commons Recommended Citation Fukasawa, Azusa, "A study of the size of nuclear fuel carriers, the most required ships for safety : how large can ship's tonnage be?" (2013). World Maritime University Dissertations. 228. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/228 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden A STUDY OF THE SIZE OF NUCLEAR FUEL CARRIERS, THE MOST REQUIRED SHIP FOR SAFETY How large can ship’s tonnage be? By AZUSA FUKASAWA Japan A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In MARITIME AFFAIRS (MARITIME SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATION) 2013 Copyright Azusa Fukasawa, 2013 DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. -

Work Profile of Maritime Pilots in Germany

Int Marit Health 2020; 71, 4: 275–277 10.5603/IMH.2020.0046 www.intmarhealth.pl REVIEW ARTICLE Copyright © 2020 PSMTTM ISSN 1641–9251 Work profile of maritime pilots in Germany Marcus Oldenburg1 , Lukas Belz1 , Filip Barbarewicz1 , Volker Harth1 , Hans-Joachim Jensen1, 2 1Institute for Occupational and Maritime Medicine Hamburg (ZfAM), University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Germany 2Flensburg University of Applied Sciences, Germany ABSTRACT Long and irregular shifts, unforeseeable operations and high responsibility are still prominent in the job of a pilot and pose high psycho-physical demands. Furthermore, there is a disturbed work-family balance. Working hours of pilots are highly variable and not bound by regulations due to irregularities of vessel traffic. The pilots have to work in a shifting rotation system. This paper demonstrates the stressors during their work routine and shows the usual working profile of a pilot during their service. (Int Marit Health 2020; 71, 4: 275–277) Key words: pilot, work profile, stressors REVIEW With annual more than 100,000 vessel movements, the In the frame of globalisation and increasing trading German Bight features one of the highest ship densities of relations, international trade takes a key position in world the world. This amount of traffic, with the ongoing trend to economy. Almost 90% of modern global trade is depend- larger vessels, enhances the risk of collisions and accidents ing on sea transport. For this sector, seafarers, who are with catastrophic impacts. Since 2015 there have been at exposed to harsh conditions during ship operations, are least 112 maritime accidents in German waters each year [6].