Evaluation of the H-2A Alien Labor Certification Process and the U.S. Farm Labor Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968)

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Carney, “With Electric Breath” “With Electric Breath”: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968) Court Carney In 1956, police in New Jersey apprehended Woody Guthrie on the presumption of vagrancy. Then in his mid-40s, Guthrie would spend the next (and last) eleven years of his life in various hospitals: Greystone Park in New Jersey, Brooklyn State Hospital, and, finally, the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, where he died. Woody suffered since the late 1940s when the symptoms of Huntington’s disease first appeared—symptoms that were often confused with alcoholism or mental instability. As Guthrie disappeared from public view in the late 1950s, 1,300 miles away, Bob Dylan was in Hibbing, Minnesota, learning to play doo-wop and Little Richard covers. 1 Young Dylan was about to have his career path illuminated after attending one of Buddy Holly’s final shows. By the time Dylan reached New York in 1961, heavily under the influence of Woody’s music, Guthrie had been hospitalized for almost five years and with his motor skills greatly deteriorated. This meeting between the still stylistically unformed Dylan and Woody—far removed from his 1940s heyday—had the makings of myth, regardless of the blurred details. Whatever transpired between them, the pilgrimage to Woody transfixed Dylan, and the young Minnesotan would go on to model his early career on the elder songwriter’s legacy. More than any other of Woody’s acolytes, Dylan grasped the totality of Guthrie’s vision. Beyond mimicry (and Dylan carefully emulated Woody’s accent, mannerisms, and poses), Dylan almost preternaturally understood the larger implication of Guthrie in ways that eluded other singers and writers at the time.2 As his career took off, however, Dylan began to slough off the more obvious Guthrieisms as he moved towards his electric-charged poetry of 1965-1966. -

A Student Companion To

A Student Companion To With the generous support of Jane Pauley and Garry Trudeau The Raymond Foundation Contents section 1: The Book and Its Context page 2 Who Was John Steinbeck? | Ellen MacKay page 3What Was the Dust Bowl? | Ellen MacKay page 6 Primary Sources Steinbeck Investigates the Migrant Laborer Camps Ellen MacKay: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and the Look of the Dust Bowl The Novel’s Reception The Wider Impact of The Grapes of Wrath page 10 What Makes The Grapes of Wrath Endure? Jonathan Elmer: Steinbeck’s Mythic Novel George Hutchinson: Hearing The Grapes of Wrath Christoph Irmscher: Teaching The Grapes of Wrath section 2: Sustainability, Bloomington, and the World of The Grapes of Wrath page 14 What Does Literature Have to Do with Sustainability? | Ellen MacKay page 15 Nature Writing Now: An Interview with Scott Russell Sanders An Excerpt from A Conservationist Manifesto | Scott Russell Sanders page 18 What Can Be Done?: Sustainablilty Then and Now Michael Hamburger Sara Pryor Matthew Auer Tom Evans page 22 Primary Access: The 1930s in Our Midst Ellen MacKay: Thomas Hart Benton, the Indiana Murals, and The Grapes of Wrath Nan Brewer: The Farm Security Administration Photographs: A Treasure of the IU Art Museum Christoph Irmscher: “The Toto Picture”: Writers on Sustainability at the Lilly Library section 3: The Theatrical Event of The Grapes of Wrath page 26 How Did The Grapes of Wrath Become a Play? | Ellen MacKay page 27 The Sound of The Grapes of Wrath: Ed Comentale: Woody Guthrie, Dust Bowl Ballads, and the Art and Science of Migratin’ Guthrie Tells Steinbeck’s Story: The Ballad of “The Joads” page 31 Another Look at the Joads’ Odyssey: Guthrie’s Illustrations. -

The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography

LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations William H. Hannon Library 8-2014 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey Gatten Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Gatten, Jeffrey, "The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography" (2014). LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations. 91. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs/91 This Article - On Campus Only is brought to you for free and open access by the William H. Hannon Library at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Music and Society, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 4, 464–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.834749 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey N. Gatten This bibliography updates two extensive works designed to include comprehensively all significant works by and about Woody Guthrie. Richard A. Reuss published A Woody Guthrie Bibliography, 1912–1967 in 1968 and Jeffrey N. Gatten’s article “Woody Guthrie: A Bibliographic Update, 1968–1986” appeared in 1988. With this current article, researchers need only utilize these three bibliographies to identify all English- language items of relevance related to, or written by, Guthrie. Introduction Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–67) was a singer, musician, composer, author, artist, radio personality, columnist, activist, and philosopher. By now, most anyone with interest knows the shorthand version of his biography: refugee from the Oklahoma dust bowl, California radio show performer, New York City socialist, musical documentarian of the Northwest, merchant marine, and finally decline and death from Huntington’s chorea. -

Still on the Road Session Pages: 1961

STILL ON THE ROAD 1961 FEBRUARY OR MARCH East Orange, New Jersey The Home of Bob and Sid Gleason, “The East Orange Tape” MAY 6 Branford, Connecticut Montewese Hotel, Indian Neck Folk Festival Minneapolis, Minnesota Unidentified coffeehouse, “Minnesota Party Tape 1961” JULY 29 New York City, New York Riverside Church, Hootenanny Special SEPTEMBER 6 New York City, New York Gaslight Café, “The First Gaslight Tape” Late New York City, New York Gerde's Folk City 30 New York City, New York Columbia Recording Studios, Carolyn Hester studio session OCTOBER 29 New York City, New York WNYC Radio Studio Late New York City, New York Folklore Center NOVEMBER 4 New York City, New York Carnegie Chapter Hall 20, 22 New York City, New York Studio A, Columbia Recordings, Bob Dylan recording sessions Late New York City, New York Unidentified Location, Interview conducted by Billy James 23 New York City, New York The Home Of Eve and Mac McKenzie DECEMBER 4 New York City, New York The Home Of Eve and Mac McKenzie 22 Minneapolis, Minnesota The Home Of Bonnie Beecher, Minnesota Hotel Tape Bob Dylan sessions 1961 20 The Home of Bob and Sid Gleason East Orange, New Jersey February or March 1961 1. San Francisco Bay Blues (Jesse Fuller) 2. Jesus Met The Woman At The Well (trad.) 3. Gypsy Davey (trad., arr Woody Guthrie) 4. Pastures Of Plenty (Woody Guthrie) 5. Trail Of The Buffalo (trad., arr Woody Guthrie) 6. Jesse James (trad.) 7. Car, Car (Woody Guthrie) 8. Southern Cannonball (R. Hall/Jimmie Rodgers) 9. Bring Me Back, My Blue-Eyed Boy (trad.) 10. -

Woody Guthrie

120742bk Woody 10/6/04 3:59 PM Page 2 1. Talking Dust Bowl Blues 2:43 9. Jesus Christ 2:45 16. This Land Is Your Land 2:17 19. Talking Columbia Blues 2:37 (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) Victor 26619, mx BS 050146-2 Asch 347-3, mx MA 135 Folkways FP 27 Disc 5012, mx D 202 Recorded 26 April 1940 Recorded c. April 1944 Recorded c. 1945 Recorded c. April 1947 2. Blowin’ Down This Road 3:05 10. New York Town 2:40 17. Pastures Of Plenty 2:31 Woody Guthrie, vocal and guitar (Woody Guthrie–Lee Hays) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) All selections recorded in New York Victor 26619, mx BS 050150-1 With Cisco Houston Disc 5010, mx D 199 Recorded 26 April 1940 Asch 347-3, mx MA 21 Recorded c. April 1947 Transfers & Production: David Lennick 3. Do Re Mi 2:38 Recorded 19 April 1944 18. Ramblin’ Blues 2:19 Digital Noise Reduction by K&A Productions Ltd (Woody Guthrie) 11. Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little (Woody Guthrie) Original recordings from the collections of David Victor 26620, mx BS 050153-1 Feet 2:35 Disc 5011, mx D 201 Lennick & John Rutherford Recorded 26 April 1940 (Traditional) Recorded c. April 1947 4. Tom Joad 6:31 With Cisco Houston Asch 432-4, mx MA 27 Original monochrome photo of Woody Guthrie from Rue des Archives/Lebrecht Music & Arts; (Woody Guthrie) background from Corbis Images. Victor 26621, mx BS 050159-1, 050152-1 Recorded 19 April 1944 Recorded 26 April 1940 12. -

Historical Studies Journal 2011

PASTURES OF PLENTY: HISTORICAL STUDIES JOURNAL Woody Guthrie in the West .Volume 28 Spring 2011 FROM EXCLUSION TO SAKURA SQUARE: University of Colorado Denver A Chronicle of Japanese-Americans in Denver, 1942-1976 RiNo: From Then to Now FIVE ALLEGED VICTIMS PRESERVATION AND RESTORATION OF HISTORIC GHOST SIGNS IN COLORADO’S FRONT RANGE HISTORICAL STUDIES JOURNAL Spring 2011 . Vol. 28 HISTORICAL STUDIES JOURNAL Spring 2011 .Volume 28 EDITORS: Kathleen Barlow EDITORIAL STAFF: Maureen Carey, Graduate Student Carrie Hartley, Graduate Student Craig Leavitt, Graduate Student Erica Poggenpohl, Graduate Student Shannon Sharkey, Graduate Student Joseph Sokolowski, Undergraduate Student Rebecca A. Hunt, Ph.D., Faculty Advisor Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D., Faculty Advisor Alison Shah, Ph.D., Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Clicks! Copy & Printing Services Auraria Campus DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY University of Colorado Denver Myra Rich, Ph.D. Pamela Laird, Ph.D. U. S. Colonial, U. S. Early National, U. S. Social, Intellectual, Technology, Women and Gender, Immigration Public History, Business History Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Department Chair 20th Century U. S. History, Urban Modern Britain, European Women History, Social Movement History, and Gender, Medicine and Health History of Crime and Policing Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Thomas Andrews, Ph.D. American West, Art & Architecture, 19th and 20th Century U. S. History, Public History & Preservation Environment, Labor, Urban, Native American, U. S. West, and History Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Education Intellectual History (European and American), Modern Europe James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. American West, Civil War, Alison Shah, Ph.D. Environmental, Film History South Asia, Islamic World, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. -

An Intimate Look Back at 1968

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2019 Nothing Is Revealed: An Intimate Look Back at 1968 Aaron Barlow CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/462 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Nothing Is Revealed An Intimate Look Back at 1968 Aaron Barlow Cover Photo by Atlas Green (CC0) Published by: Brooklyn, NY 2019 ISBN-13: 9781697690675 PUBLISHED UNDER AN ATTRIBUTION-NONCOMMERCIAL-SHAREALIKE CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE ii For all of those who didn’t make it far enough to be able to look back ii Introduction This project isn’t simply one of memoir. It’s a cultural study from a personal base, one created, also, through a unique temporal framework, a moving narrative composed of blog posts each focused on the exact day fifty years earlier. Its sub- jectivity is deliberate, for the intent is to provide an impression of a significant year through the eyes of a young man in the process of coming of age. It’s also a political tale sparked by the rise of Donald Trump to the Presiden- cy of the United States, one detailing the seeds of that rise and the false populism and white nationalism that are still buoying him in 2019. Sexual violence. Racial violence. Political violence. -

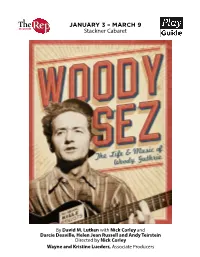

JANUARY 3 – MARCH 9 Stackner Cabaret

JANUARY 3 – MARCH 9 Stackner Cabaret By David M. Lutken with Nick Corley and Darcie Deaville, Helen Jean Russell and Andy Teirstein Directed by Nick Corley Wayne and Kristine Lueders, Associate Producers Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents Woody Sez PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Neal Easterling Education Associate January 7 – February 9 • Stackner Cabaret Play Guide edited by By David M. Lutken with Nick Corley and Leda Hoffmann Darcie Deaville, Helen Jean Russell and Andy Teirstein Literary Coordinator Directed by Nick Corley Lindsey Hoel-Neds Wayne and Kristine Lueders, Associate Producers Education Assistant Lisa Fulton Director of Marketing & MARK’S TAKE Communications “After seeing this beautifully-crafted piece in Chicago, I knew that we had to bring it to Milwaukee. Even though • Woody Guthrie wrote songs responding to the people and events of a particular period, like any other pieces of great Graphic Design by art, his songs still rouse the heart, capture the imagination, Eric Reda and resonate just as strongly today as when they were first written—true classics!” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis & Performers ......................................................3 Woody’s Timeline ...........................................................4 The Visual Artwork of Woody Guthrie ........................................6 About the Dust Bowl ........................................................7 Mark Clements Artistic Director People of Woody Sez ........................................................8 -

Prophet Singer: the Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Mark Allan, "Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROPHET SINGER: THE VOICE AND VISION OF WOODY GUTHRIE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Mark Allan Jackson B.A., Hendrix College, 1988 M.A., University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1995 December 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people and institutions should be acknowledged for their help in making my dissertation possible. I have to start off by tipping my hat to certain of my friends, people who first asked me interesting questions or spared with me in argument about music. So I salute Casey Whitt, John Snyder, Cody Walker, Derek Van Lynn, Maxine Beach, and Robin Becker. They helped me see the deep places in America’s music, made me think about its beauty and meaning. -

Woody Guthrie: “The True Voice of the American Spirit”

Woody Guthrie: “The true voice of the American spirit” The Tribute Concerts – Carnegie Hall 1968, Hollywood Bowl 1970 Liz Thomson Some will rob you with a six-gun And some with a fountain pen.… I was around 12 years old when I first heard those lines, from “Pretty Boy Floyd”, written by Woody Guthrie and sung by Joan Baez on a live album recorded on her 1962 tour of America’s black campuses. I couldn’t fathom what they meant – how could you be robbed with a fountain pen? I was in the early stages of my obsession with what I would come to understand as “the New York folk revival”, an obsession that has, in ways large and small, shaped my life, though the revival was already long over. I’m not sure when I figured out what the words meant but, as the years have passed, they seem ever more apposite, summing up much of what has happened to the world over the last decade to the 99 Percent who lost out to banksters and corporate interests. Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd” was an Oklahoman Robin Hood figure. He was not as benevolent in real life as in Guthrie’s song, but that does nothing to devalue the lines themselves, even though fountains pens and ledgers long ago gave way to computers and spreadsheets. It’s now half a century since Woody Guthrie died, on 3 October 1967, and most notable among the projects marking the anniversary is the lovingly curated boxed set from Bear Family Records of Woody Guthrie: The Tribute Concerts – Carnegie Hall 1968, Hollywood Bowl 1970. -

Song Lyrics with Translations

SONG LYRICS WITH TRANSLATIONS De Colores In Colors Traditional - Mexican Folk Song Traditional - Mexican Folk Song De colores, de colores se visten los campos en la In colors, the fields drape themselves in profusion primavera of colors in springtime. In colors, in colors the young De colores, de colores son los pajarillos que vienen birds arriving from afar de afuera In colors, in colors the brilliant rainbow we De colores, de colores es el arco iris que vemos lucir spy Y por eso los grandes amores de muchos And that’s why the great love of infinite colores me gustan a mi Y por eso los grandes colors is pleasing to me And that’s why the amores de muchos colores me gustan a mi great love of infinite colors is pleasing to me Canta el gallo, canta el gallo con el quiri quiri quiri quiri quiri The rooster sings, the rooster sings with a cock-a- La gallina, la gallina con el cara cara cara cara cara doodle-do (kiri, kiri) The hen, the hen with a cluck, Los polluelos, los polluelos con el pio pio pio pio pi cluck, cluck (kara, kara) Y por eso los grandes amores de muchos The baby chicks, the baby chicks with a cheep, colores me gustan a mi Y por eso los grandes cheep, cheep (pio, pio) amores de muchos colores me gustan a mi And that’s why the great love of infinite Canta el gallo, canta el gallo con el quiri quiri quiri colors is pleasing to me And that’s why the quiri quiri great love of infinite colors is pleasing to me La gallina, la gallina con el cara cara cara cara cara Los polluelos, los polluelos con el pio pio pio pio pi The rooster sings, the rooster sings with a cock-a- doodle-do (kiri, kiri) The hen, the hen with a cluck, Y por eso los grandes amores de muchos cluck, cluck colores me gustan a mi Y por eso los grandes (kara, kara) amores de muchos colores me gustan a mi The baby chicks, the baby chicks with a cheep, cheep, cheep (pio, pio) And that’s why the great love of infinite colors is pleasing to me And that’s why the great love of infinite colors is pleasing to me (translated by Abby F. -

02. Fenton, Poetic Motion

ISSN 2053-8804 Woody Guthrie Annual, 3 (2017): Fenton: Guthrie’s Poetic Motion “A Dance That Is Danced Standing Still”: Poetic Motion in the Work of Woody Guthrie1 ! Jamie Fenton! ! Today you’re a better songbird than you was yesterday, ‘cause you know a little bit more, you seen a little bit more, and all you got to do is just park yourself under a shade tree, or maybe at a desk, if you still got a desk, and haul off and write down some way you think this old world could be fixed so’s it would be twice as level and half as steep, and take the knocks out of it, and grind the valves, and tighten the rods, and take up the bearings, and put a boot in the casing, and make the whole trip a little bit smoother, and a little bit more like a trip instead of a trap (Woody Guthrie, “Introduction,” Hard Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People)2 ! Woody Guthrie writes the troubled world of 1940s America as an engine which needs fixing. This “old world” is going somewhere, towards a new, more global world, and it is the job of the writer, who is “you,” everyone, to get things in shape for the journey. In a mixed metaphor of total movement, the engine is also the road on which it runs, which needs to be “twice as level and half as steep,” a tautology which performs its own sort of flattening on the sentence. Only after all the work of grinding, tightening and taking-up will the world be made “a little bit more like a trip instead of a trap.” This last phrase does some more fixing-up work, showing us how “trap” can been repurposed, smoothed into “trip.” “[A] little bit more like a trip instead of a trap” also trips, tumbling lightly over the assonance of “little […] bit […] trip […] trap.” And it is only at the full stop, the punctuation which traps the sentence, that we realize the length of the trip from where and when we set off: “Today.” We become better songbirds over the course of the long sentence.