03. Chemistry Sets 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Manual!

EXPERIMENT MANUAL Please observe the safety information, first aid information, information about hazardous substances, and poison control information on the inside front cover; the advice for supervising adults on page 3; and the safety rules on page 4. WARNING. WARNING — Chemistry Set. Not suitable for children This set contains chemicals and/ under 6 years. For use or parts that may be harmful under adult supervision. if misused. Read cautions on Read the instructions individual containers and in manual before use, follow them and carefully. Not to be used by children keep them for reference. except under adult supervision. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG, Pfizerstr. 5-7, 70184 Stuttgart, Germany | +49 (0) 711 2191-0 | www.kosmos.de Thames & Kosmos, 301 Friendship St., Providence, RI, 02903, USA | 1-800-587-2872 | www.thamesandkosmos.com › › › SAFETY INFORMATION Safety Information ››› WARNING. Not suitable for children under 3 years. Choking Poison Control Centers hazard — small parts may be swallowed or inhaled. (United States) ››› Keep the packaging and instructions as they contain important information. In case of emergency, your nearest poison First Aid Information control center can be ››› In case of eye contact: Wash out eye with plenty of water, reached everywhere in holding eye open. Seek immediate medical advice. the United States by ››› If swallowed: Wash out mouth with water, drink some fresh dialing the number: water. Do not induce vomiting. Seek immediate medical advice. ››› In case of inhalation: Remove person to fresh air. ››› In case of skin contact and burns: Wash affected area with 1-800-222-1222 plenty of water for at least 10 minutes. -

CHEM C3000 Manual

EXPERIMENT MANUAL Version 2.0 Please observe the safety information, the advice for supervising adults on page 5, the safety rules on page 6, the information about hazardous substances and mixtures (chemicals) on pages 7-9 and their environmentally sound disposal on pages 175-177, the safety for experiments with batteries on page 192, the first aid information on the inside front cover and the instructions on the use of the alcohol burner on page 12. WARNING. Not suitable for children under 12 years. For use under adult supervision. Contains some chemicals which present a hazard to health. Read the instructions before use, follow them and keep them for reference. Do not allow chemicals to come into contact with any part of the body, particularly the mouth and eyes. Keep small children and animals away from experiments. Keep the experimental set out of the reach of children under 12 years old. Eye protection for supervising adults is not included. WARNING — Chemistry Set. This set contains chemicals and parts that may be harmful if misused. Read cautions on individual containers and in manual carefully. Not to be used by children except under adult supervision. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG, Pfizerstr. 5-7, 70184 Stuttgart, Germany | +49 (0) 711 2191-0 | www.kosmos.de Thames & Kosmos, 301 Friendship St., Providence, RI, 02903, USA | 1-800-587-2872 | www.thamesandkosmos.com Thames & Kosmos UK Ltd, Goudhurst, Kent, TN17 2QZ , United Kingdom | 01580 212000 | www.thamesandkosmos.co.uk Contents Safety and Information First Aid Information . Inside front cover Poison Control Contact Information . Inside front cover Advice for Supervising Adults . -

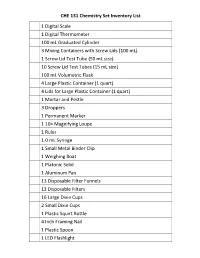

CHE 131 Chemistry Set Inventory List 1 Digital Scale 1 Digital

CHE 131 Chemistry Set Inventory List 1 Digital Scale 1 Digital Thermometer 100 mL Graduated Cylinder 3 Mixing Containers with Screw Lids (100 mL) 1 Screw Lid Test Tube (50 mL size) 10 Screw Lid Test Tubes (15 mL size) 100 mL Volumetric Flask 4 Large Plastic Container (1 quart) 4 Lids for Large Plastic Container (1 quart) 1 Mortar and Pestle 3 Droppers 1 Permanent Marker 1 10× Magnifying Loupe 1 Ruler 1.0 mL Syringe 1 Small Metal Binder Clip 1 Weighing Boat 1 Platonic Solid 1 Aluminum Pan 13 Disposable Filter Funnels 13 Disposable Filters 16 Large Dixie Cups 2 Small Dixie Cups 1 Plastic Squirt Bottle 4 Inch Framing Nail 1 Plastic Spoon 1 LED Flashlight 3 AAA Batteries 1 Blue Light Filter 11 Square Plastic Cuvettes (4.5 mL) 2 Squares (1.0 inch) of Double Stick Tape 1 Conductivity Apparatus consisting of: - Conductivity Sensor/Electrode - 12 Volt Green LED - 3 Volt Power Supply 1 Microfiber Rag Packet of Blue Litmus Paper Packet of Red Litmus Paper 2 Bottles Deionized Water 1 Large Dixie Cup Full of Lego Pieces 1 Gray Lego Board 1 Roll of Duct Tape 1.0 mL of Brilliant Blue FCF (Blue FC in an Eppendorf Tube) 15 mL of 1.0 % Acetic Acid (in a 15 mL Screw Lid Test Tube) 2.0 grams of L-Arginine 1 Baggie Full of Citric Acid 1 Baggie Full of Magnesium Sulfate Heptahydrate 1 Baggie Full of Sodium Chloride 1 Baggie Full of Sucrose 1 Baggie Full of Calcium Chloride Dihydrate 1 Baggie Full of Urea Calcium Sulfate Packet containing: 1) Materials Safety Data Sheets for all enclosed chemicals 2) Copies of all experimental laboratory procedures CHE 132 -

Chemistry Lab Kit Instructions

CHEMISTRY LAB KIT INSTRUCTIONS Not suitable for children under 10 years. For use under WARNING! adult supervision. Contains some chemicals which present a hazard to health. Read the instructions before use, follow them and keep them for reference. Do not allow chemicals to come into contact with any part of the body, particularly mouth and eyes. Keep small children and animals away from experiments. Keep the experimental set out of reach of children under 10 years old. Eye protection for supervising adults is not included. MADE IN CHINA P38-CM001-81001003 CONTENTS : 2 Test Tubes with Stoppers 1 Cleaning Brush 1 Test Tube Holder 2 Glass Tubing 1 Rubber Tubing 1 Spirit Lamp 1 Beaker(0-100ml) 1 Stirring Rod 1 Measuring Spoon 6 Filter Papers 8 Universal Indicator Paper 1 Goggles 2 Cork Stoppers with hole 1 Funnel 2 Cork Stoppers 1 Instruction Book 1 Scoop 1 Dropping Pipette 1 Test Tube Rack The Safety Rules Read these instructions before use, follow them and keep them for reference. Keep young children, animals and those not wearing eye protection away from the experimental area. Always wear eye protection. Store this experimental set out of reach of children under 10 years of age. Clean all equipment after use. Make sure that all containers are fully closed and properly stored after use. Ensure that all empty containers are disposed of properly; Wash hands after carrying out experiments. DO NOT use any equipment which has not been supplied with the set or recommended in the instructions for use. DO NOT eat or drink in the experimental area. -

Professor Richard Schrock

1/9/13 Richard R. Schrock - Autobiography The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2005 Yves Chauvin, Robert H. Grubbs, Richard R. Schrock Richard R. Schrock Born: 4 January 1945, Berne, IN, USA Affiliation at the time of the award: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USA Prize motivation: "for the development of the metathesis method in organic synthesis" Field: Organic chemistry Photo: L.B. Hetherington Autobiography I was born in Berne, a northeast Indiana farming community proud of its Swiss heritage. Life was not easy for my parents, Noah J. Schrock, the second of six children, and Martha A. Habegger, the second of ten children. They married in 1933 during the Depression. My oldest brother, Luther, was born in 1934, Theodore in 1939. A few months after I appeared in 1945, the family moved to Decatur, about 13 miles north of Berne, where we lived until the summer after my fifth birthday. My most lasting memory of our first home is its proximity to the city swimming pool where I spent many happy summer days. We moved into an old house on the west side of South 13th Street in 1950. The house required a good deal of work, but my father, who had been a carpenter for fifteen years, accomplished the renovation over a period of several years. The house was located on what seemed to me to be an enormous plot of land (one acre); the backyard took forever to mow on a steamy summer day and the vegetable garden produced quantities of corn, strawberries, melons, tomatoes, and raspberries. -

Purchase Guide

STANDARD CHEMISTRY LABORATORY SUPPLIES Purchase Guide from SCIENTIFIC “Your Safer Source for Science” .. 21 tvi, I 010 00 2121 F 21 Online: www.flinnsci.com Email Order to: [email protected] esite .flinnsci.c il flinnflinnsci.c Mail Order to: Flinn Scientific, Inc. P.O. Box 219 Page Total: _______________________ Batavia, IL 60510 Fax 1-866-452-1436 © 2017 Flinn Scientific, Inc. All Rights Reserved. FLINN SCIENTIFIC Standard Chemistry Laboratory Supplies 2017 Edition Purchase Guide Easy Ordering Instructions 1) Conduct an inventory of chemicals and apparatus on hand using the “Current Inventory Status” column. 2) Decide how much of each supply item you will need for future laboratory work. 3) Order needed chemicals and apparatus using the “Quantity Ordered” column. 4) Prices guaranteed until January 31, 2018. 5) To submit your order: Online: www.flinnsci.com Email Order to: [email protected] Fax Order to: 1-866-452-1436 Mail Order to: Flinn Scientific, Inc. P.O. Box 219 Batavia, IL 60510 © 2017 Flinn Scientific, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Available from Flinn Scientific Current Inventory Quantity Quantity Unit Catalog Product/Item Name Status Recommended Ordered Price Total Price Number Chemistry—Apparatus Apron, rubberized, 27" W X 36" L 30 $12.75 AP7125 Pioneer Analytical Balance, 210 x 0.0001 g 2 $2,193.50 OB2151 Balance, electronic, 210 g X 0.01 g, Flinn 6 $298.00 OB2141 Beaker brush, nylon 12 $12.10 AP8409 Bottle, dropping, 30-mL dispenser 48 $1.45 AP1221 Bottle, wash, polyethylene, 250-mL 18 $4.30 AP8108 Bulb, rubber, red, -

Crystal Growing Set, You Will Be Accompanying Water Supply

EXPERIMENT MANUAL Please observe the safety information, the advice for supervising adults on page 4, the safety rules on page 5, the information regarding the handling of the chemicals and their environmentally sound disposal on pages 6 to 9, and the first aid information. WARNING. Not suitable for children under 10 years. For use under adult supervision. Contains some chemicals which present a hazard to health. Read the instructions before use, follow them and keep them for reference. Do not allow chemicals to come into contact with any part of the body, particularly the mouth and eyes. Keep small children and animals away from experiments. Keep the experimental set out of reach of children under 10 years old. WARNING — Chemistry Set. This set contains chemicals and parts that may be harmful if misused. Read cautions on individual containers and in manual carefully. Not to be used by children except under adult supervision. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG, Pfizerstr. 5-7, 70184 Stuttgart, Germany | +4 9 (0) 711 2191-0 | www.kosmos.de 643522-03-060515 Thames & Kosmos, 301 Friendship St., Providence, RI, 02903, USA | 1-800-587-2872 | www.thamesandkosmos.com Thames & Kosmos UK Ltd, Goudhurst, Kent, TN17 2QZ , United Kingdom | 01580 212000 | www.thamesandkosmos.co.uk › › › SAFETY INFORMATION FIRST AID… …in case any accidents First Aid should happen during Information experimentation. Kosmos Quality and Safety ››› I n case of eye contact: Wash out eye with plenty of Poison Control Centers (United States) More than one hundred years of expertise in publishing science ex- water, holding eye open if necessary. -

SMITHSONIAN Chem-Works Microchemistry

Additional SupplyNeeds (to be suppliedby you) WARNING: THISSET CONTAINS CHEMICALS & APPARATUS Your Microchemistry set includes all of the special chemicals and materials to provide you with the reagent chemicals and equipmentto perform experiments and provide you with hours of educational fun. Since there are so manyexperiments and procedures, you are THATMAY BE HARMFUL IF MISUSED. READ asked to supply manyof the commonhousehold items and household chemicals which would be impractical to supply and ship in your ITEM #2835 chemistry set. AGES 10 AND UP CAUTIONSONINDIVIDUAL CONTAINERS Youwill need to gather various items listed in each experiment so that you can perform the experiments. Always read through your experimentbeforehand and gather all of the materials you will needat the beginning. CAREFULLY.NOTTO BE USED BY CHILDREN Thefollowing list of outside items and materials is listed below for your convenience.You DO NOT need to collect ALLitems on the list EXCEPTUNDER ADULT SUPERVISION. at one time, only as you plan aheadto perform a particular experimentor series of experiments. Plastic sheeting for work area Lemonjuice paper towels for cleanup 3% solution hydrogen peroxide Cotton or cotton balls Fine steel wool Scissors Rawliver ,® Distilled water Raw potato Isopropyl RubbingAlcohol or Ethyl RubbingAlcohol Grassclippings and/or plant leaf SMITHSONIAN Cardstock (3" x 5" filing card) Sunlight and/or strong artificial light source Pencils (red and black) Sodiumbicarbonate (baking soda) Ball point pen Alka Seltzer~ tablet Kitchen paring knife Teaspoon Chem-Works Fine sandpaper Toothbrush Sheet of white paper Window pane Liquid dishwashing soap Woodenruler MicroChemistry Hair shampoo Set of colored pencils Dishwasher Jet-Dry @soap Flower petals Liquid hand soap Plant fruit skins i.e. -

Association of Indiana University Chemists Alumni Journal Vol

IUlCHEMISTRY Association of Indiana University Chemists Alumni Journal Vol. 62 l College of Arts and Sciences l Fall 2017 In this issue: Molecules that remove toxic elements from the environment Creating a CURE for chemistry students Undergraduates performing impactful research In Memorium: John Hayes IU •Chemistry Contents Association of Indiana University Chemists Alumni Journal 2 CHAIR’S LETTER by Stephen Jacobson Vol. 62 • College of Arts and Sciences • 4 IU CHEMIST COULD REDUCE Fall 2017 NUCLEAR WASTE by Kevin Fryling College of Arts and Sciences 5 JUDI ROBERTS HONORED WITH IU Larry D. Singell, Dean STAFF AWARD Department of Chemistry 6 CREATING A CURE FOR CHEMISTRY STUDENTS Stephen Jacobson, Chair by Matthew Barton Cathrine Reck, Editor/Photography William Unrue, Editorial Assistant 7 CHEMISTRY GRADUATE STUDENTS HELP PREPARE LOCAL TEENS FOR Cover photo: John Hayes (left) and Dennis STEM CAREERS Peters, outside of John’s backyard home by Bailey Briscoe office in Berkeley, California. On May 24, 2009, Dennis and four of his students (who 8 LYUDA BRONSTEIN’S GROUP were attending and presenting papers at the PROVIDES UNDERGRADUATES A 215th meeting of The Electrochemical Society MEANINGFUL RESEARCH EXPERIENCE in San Francisco) visited John and Janice by Lyuda Bronstein Hayes at their home. Denizens of the 1930 portion of the IU Chemistry Building, before 12 IU CHEMISTS CREATE MOLECULAR it was remodeled in the late 1980s, just might recognize the sign in the photograph “LEAF” between John and Dennis. For many years, by Kevin Fryling the sign was in the hallway of the “old” chemistry building to indicate the location of AROUND CHEMISTRY the Main Office complex, which combined all 14 Conferences, Special Lectures, & the functions now found in the modern and Symposia separate Chairman’s and Business Offices. -

A History of Modern Psychology, 10Th

This page intentionally left blank This page intentionally left blank A History of Modern Psychology TENTH EDITION DUANE P. SCHULTZ University of South Florida SYDNEY ELLEN SCHULTZ Australia • Brazil • Japan • Korea • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • United Kingdom • United States This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions, some third party content may be suppressed. Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. The publisher reserves the right to remove content from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. For valuable information on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate formats, please visit www.cengage.com/highered to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for materials in your areas of interest. A History of Modern Psychology, © 2011 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Tenth Edition ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright Duane P. Schultz and Sydney Ellen herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used in any form or by Schultz any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribu- Senior Publisher: Linda Schreiber-Ganster tion, information networks, or information storage and retrieval sys- Executive Editor: Jon-David Hague tems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United Editorial Assistant: Sheli DeNola States Copyright -

The Ageless Gergel

TO THE UNCAGED GERGEL: LONG MAY HE SING! If you already know Max Gergel, skip this preface. You'll want to get directly to the interesting part of this book. For that matter, if you don't know Max Gergel, you can also skip this preface with very little loss. It's a rather fulsome declaration of affection for one of the world's truly unique, truly unforgettable characters. Life with — or even near — Max is never boring. The man's vitality is downright awesome, as is his cheerful zest for living and his enormous affection for his fellow man (and woman!) If Max is somewhat slowed up (as he cheerfully complains) in his present "youthful old age," it's not readily apparent to most of his colleagues. He continues to maintain a level of personal and professional activity that would wear out most of us just contemplating his current international jet-hopping. I don't really think of Max as "growing" on someone — more accurately, he "explodes" on you and you are immediately a full- fledged family member for ever thereafter. In a way, it's rather too bad that Max chose Chemistry as a profession. From Max's many lectures, the world is only beginning to realize that it lost a world-class comic in the process. No matter how many times I hear the story of Preacher's unpublished synthesis recipes, I laugh anew. To hear Max tell of his adventures and misadventures with his family, his employees, the government, his neighbors, his competitors — anyone with whom Max has had an interface — is to be reminded of the human condition and (tragedies notwithstanding) how, in Max's hands, never-endingly interesting it continues to be. -

Only for Use by Children Over10 Years Old . to Be Used Solely Under the Strict Supervision of Adults That Have Studied

WARNING! ONLY FOR USE BY CHILDREN OVER10 YEARS OLD TO BE USED SOLELY UNDER THE STRICT SUPERVISION OF ADULTS THAT HAVE STUDIED THE PRECAUTIONS GIVEN IN THE EXPERIMENTAL SET CONTAINS SOME CHEMICALS WHICH ARE CLASSIFIED AS A SAFETY HAZARD READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE USE, FOLLOW THEM AND KEEP THEM FOR REFERENCE DO NOT ALLOW CHEMICALS TO COME INTO CONTACT WITH ANY PART OF THE BODY, PARTICULARLY THE MOUTH AND EYES KEEP SMALL CHILDREN AND ANIMALS AWAY FROM EXPERIMENTS STORE THE CHEMISTRY SET OUT OF REACH OF SMALL CHILDREN EYE PROTECTION FOR SUPERVISING ADULTS IS NOT INCLUDED. CHEMICALS CAS NO EINECS NO Copper (11) Sulphate (CuSo45H20)HARMFUL HARMFUL: IF SWALLOWED. DANGEROUS IRRITATINGTO EYES 7758-98-7 2318476 AND SKIN.VERYTOXICTO AQUATIC ORGANISMS, MAY CAUSE LONG-TERM ADVERSE EFFECTS IN THE AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT.DO NOT BREATHE DUST.THIS MATERIALAND ITS CONTAINER MUST BE DISPOSED OF AS HAZARDOUS WASTE.AVOID RELEASE TO THE ENVIRONMENT.REFER TO SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS/SAFETY DATA SHEET. Ammonium Chloride (NH4CI)HARMFUL IF SWALLOWED. HARMFUL IRRITATINGTO EYES. 12125-02-9 2351864 DO NOT BREATHE DUST. Calcium Hydroxide Ca(OH)2 CORROSIVEIRRITANT. 1305-62-0 2151373 Sodium Carbonate (Na2CO310H20)IRRITATING TO EYES. IRRITANT DO NOT BREATHE DUST.IN 497-19-8 2078388 CASE OF CONTACTIrritating to WITH eyes EYES, RINSE IMMEDIATELYWITHDo PLENTYnot breathe OF WATERAND SEEK MEDICALDust.Wear ADVICE. Sodium Hydrogen Sulphate RISK OF SERIOUSCORROSIVE DAMAGE TO EYES. 7681-38-1 2316657 NaHS04H20AVOID CONTACT Causes burns WITH SKIN. IN CASE OF CONTACT WITH EYES, RINSE IMMEDIATELYWITH PLENTY OF WATERAND SEEK MEDICAL ADVICE. Aluminium Potassium Sulphate 10043-67-1 2331413 K2S04AI2 (S04)324H20) Zinc (Zn)CONTACT WITH FLAMMABLE WATER LIBERATES EXTREMELY 7440-66-6 2311753 FLAMMABLE GASES.