Royal and State Scribes in Ancient Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHOENICIANS - Oxford Reference

PHOENICIANS - Oxford Reference http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/view/10.1093... The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (2 ed.) Edited by Adele Berlin and Maxine Grossman Publisher: Oxford University Press Print Publication Date: 2011 Print ISBN-13: 9780199730049 Published online: 2011 Current Online Version: 2011 eISBN: 9780199759279 Greek name for the peoples of the Levant (greater Canaan), especially the coastal region, and used by scholars today to refer to the Canaanites of such major city-states as Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon from c. 1200 BCE onward. The Bible portrays the Phoenicians as being on friendly political terms with the Israelites. For example, King Hiram I of Tyre (c.980 BCE) made a treaty with David and Solomon, and the Phoenicians supplied the architects, workmen, and raw materials (cedar of Lebanon, especially) for the construction of David’s and Solomon’s palaces and for the Temple in Jerusalem (2 Sm. 5.11; 1 Kgs. 5.15–32, 7.13–14). The detailed biblical description of the Temple dovetails with the data from the archeological discovery of various Phoenician temples, clearly demonstrating that Solomon’s Temple was built according to the design of a Phoenician-Canaanite prototype. Solomon and Hiram also had joint maritime ventures from the Red Sea port of Ezion-geber (near Elat) to develop trade with regions to the far south and east (perhaps East Africa and India; 1 Kgs. 9.26–28, 10.11, 10.22). Later, King Ethbaal I of Sidon (c.880 BCE) appears to have entered into a treaty with Omri, marked by the marriage of their children, Ahab, later king of Israel, and Jezebel, the Phoenician princess (1 Kgs. -

Hiram, King of Tyre

HIRAM, KING OF TYRE Presented at William O. Ware Lodge of Research by Edwin L. Vardiman April 10, 1986 The name of Hiram, King of Tyre, brings recognition to all of us here tonight. As Master Masons we are aware of this man who is known as a friend of the Illustrious King Solomon, and who has a major part in the events portrayed in the Legend of the Temple. Who was this man who was in the confidence of King Solomon? What had he done, as the king of a neighboring country, to be so valuable to the Kingdom of Israel? Was he a true and living person whose life and reign were recorded in history, or was he merely a convenient symbol for the early playwright who developed the much beloved portrayal of the events in the Master Mason Degree? For a few minutes, let’s attempt to answer these questions as we think upon the connection of Hiram, King of Tyre, to our Fraternity. What of the country of Tyre? It was a real country and one that made considerable contributions to our civilization. Its origins extend back into the dim beginnings of history, and it had influence far greater than its size indicates on the ancient Mediterranean world, our language and even our world today. Tyre’s name reflects the foundation of its island existence. The basic meaning of the word “Tyre,” going back through the Greek and Hebrew words, means “rock.” Although the first settlement was on the eastern Mediterranean shore, in what is now southern Lebanon, the city did not emerge into a thriving commercial center until after it was constructed on two rock islands of no more than half a mile wide. -

11. BIBLICAL EPIC: 1 Kings Notes

11. BIBLICAL EPIC: 1 Kings Notes rown 1 Kings 1: David was very old. His son Adonijah exalted himself as king. When David heard he told Zadok and Nathan to anoint Solomon as king. 1-2 Kings, divided by convenience, describe the period of the monarchy after David in ancient Israel (970–586 BC). David’s parting speech to Solomon in ch. 2, drawing richly from Deuteronomy, sets the agenda. Beginning with Solomon, and then all the succeeding kings of Israel and Judah, the kings are weighed in relation to the Mosaic law code and found wanting. Israel’s sinfulness eventually leads to the exile to Babylon in 586 BC, but there remains hope because God’s chosen royal line has not come to an end (2 Kings 25:27-30), and God remains ready to forgive those who are repentant. The books are not merely a chronicle of events, but history from God’s perspective and how He is directing all history toward a goal. The Bible is a story about God and how His Kingdom will come. Every “son of David” that is found wanting adds to the yearning for a greater David who will sit on David’s throne forever. We could summarize the book in this way: “Ruling justly and wisely depends on obeying God’s word, and disobeying has serious consequences.” • 1:1-4. David in His Old Age. David’s waning life is seen in his inability to get warm. Ancient medical practice provided warmth for the sick by having a healthy person “lie beside” them. -

House of the Lord Sir Knights Benjamin F

House of the Lord Sir Knights Benjamin F. Hill, Knight Templar Cross of Honor Grand Commander, Grand Commandery Knights Templar of Virginia 2020 The accounts of the construction of the House of the Lord is perhaps one of the most interesting events to Freemasons on their journey to Masonic Light. It starts with the Hiram Legend in the Second Section of the Master Mason Degree; followed by Albert Mackey’s Lectures of the Destruction of Temple, Captivity of the Jews at Babylon, and the Return to Jerusalem and subsequent rebuilding of the House of the Lord in the Royal Arch Degrees; and finally, the Historical Lecture of the Grand Encampment Knights Templar in the Illustrious Order of the Red Cross, a prelude to the solemnities of the Order of the Templar. Since the earliest times, man has built temples or shrines where he could worship his own god. The Tower of Babel is the first such structure mentioned in the Bible and was probably constructed prior to 4000 BC. After receiving a Divine call to build an Israelite nation free from idolatry, Abram took possession of the land southwest of the Euphrates River and erected an altar the Lord in 2090 BC. During the second month of the Exodus, Moses made intercessions on behalf of his people, spend two forty-day periods on Mount Sinai, received a new Covenant, and directed the people to erect a Tabernacle or "tent of congregation." The early patriarchies of Israel were semi-nomadic, so their Tabernacles were temporary structures. Around 1002 BC, after consolidating his power, David became King of Judah and decided to build a permanent residence and shrine to the Lord. -

Fresh Light from the Ancient Monuments

[Frontz'spz'ece. Monument of a Hittite king, accompanied by an inscription in Hittite hieroglyphics, discovered on the site of Carchemish and now in the British Museum. Ely-{Baths of mm iitnnmlzhg: I I FRESH LIGHT EROM IHE ANCIENT MONUMENTS A SKETCH OF THE MOST STRIKING CONFIRMATIONS OF THE BIBLE FROM RECENT DISCOVERIES IN EGYPT PALESTINE ASSYRIA BABYLONIA ASIA MINOR BY A. H. EAYCE M.A. Depu/y Professor of Comparative Phi/01057 Oxfiv'd [1012. LLD. Dufilin SEVENTH EDITION THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY 56 PATERNOSTER Row 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD {87,2 THE PENNSYLVANIA sun UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PREFACE. THE object of this little book is explained by its title. Discovery after discovery has been pouring in upon us from Oriental lands, and the accounts given only ten years ago of the results of Oriental research are already beginning to be antiquated. It is useful, therefore, to take stock of our present knowledge, and to see how far it bears out that ‘ old story’ which has been familiar to us from our childhood. The same spirit of scepticism which had rejected the early legends of Greece and Rome had laid its hands also on the Old Testament, and had determined that the sacred histories themselves were but a collection of myths and fables. But suddenly, as with the wand of a magician, the ancient Eastern world has been reawakened to life by the spade of the explorer and the patient skill of the decipherer, and we now find ourselves in the presence of monuments which bear the names or recount the deeds of the heroes of Scripture. -

An Updated Chronology of the Reigns of Phoenician Kings During the Persian Period (539-333 BCE)

An Updated Chronology of the Reigns of Phoenician Kings during the Persian Period (539-333 BCE) J. ELAYI* Résumé: L’objectif de cet article est de proposer une chronologie des règnes des rois phéniciens à l’époque perse (539-333 av. notre ère), à partir de toutes les données disponibles dans l’état actuel de la documentation. Cette chronologie à jour et prudente pourra être utilisée comme base fiable par tous les spécialistes du Proche-Orient à l’époque perse. The chronology of the reigns of Phoenician kings during the Persian Period (539-333 BCE)1 is very difficult to establish for several reasons. First, the Persian period remained virtually unexplored until the last 20 years2; moreover, Phoenician studies were for a long time dependent on biblical chronology3. On the other hand, the deficiency of the sources has to be underlined. Monumental inscriptions mentioning kings and dated by the years of reign are rare in Phoenician cities, partly because many of them have disappeared in lime kilns, and perishable official *. CNRS, Paris. 1. 539 is the traditional date for the Persian conquest of Phoenician cities: see J. Elayi, Sidon cité autonome de l’Empire perse, Paris 1990², pp. 137-8. 333 is the date of the conquest of Phoenician cities by Alexander (332 for Tyre). 2. See J. Elayi and J. Sapin, Quinze ans de recherche (1985-2000) sur la Transeuphratène à l’époque perse, Trans Suppl. 8, Paris 2000; id., Beyond the River. New Perspectives on Transeuphratene, Sheffield 1998; and the series Trans, 1-32, 1989-2006. 3. Cf. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Copyright ©2004–2021 Jeffro

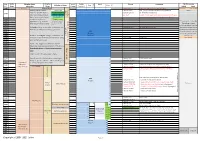

Year Tyrian Egyptian Kings Assyrian Syrian/ Judah Age Israel Age Source Comments JW Chronology Babylonian Kings Year Year (BCE) Kings (Pharaohs) Kings Persian Tishri-based Judah Israel st 1048 21 D. (Tanis) ↑ General Notes Adad-apla- 1 Samuel 8:1–9 Samuel already old before meeting Saul ↑ 1077 BCE Starts too late* Shading indicates events Unspecified iddina 1 Samuel 9:1–2 Saul “young” (unmarried) when meeting Samuel David relative to another reign or April*–September 2 Samuel 2:10–11 Ish-bosheth born (earliest) 1047 other event, indicating likely October–March Acts 13:21 Length of reign asserted in Acts not consistent with ages time of year or period; some January–March and events of Samuel, Saul, Ish-bosheth and David 1046 month names given are Possible range 1045 approximate (e.g. ‘April’ for * Or earlier for events Marduk-ahhe-eriba months), (6 * “Starts too late” in the JW based only on Tishri 1044 Nisan may be March or April) Chronology columns 1043 years indicates in relative terms that Marduk-zer- 1042 For Judah: 2 Kings , 2 Chronicles and Jeremiah use 2 Samuel 2:10–11 Ish-bosheth born (latest) the reign should start during 1041 Tishri-based dating and count accession years the same year as the previous 1040 Saul king’s final year; it does not 1039 40 years refer to the assignment of 1038 For Israel and Babylon: 2 Kings , 2 Chronicles and X (spurious) absolute years 1037 Jeremiah (except 52:28–30 ) use Nisan-based dating 2 Samuel 5:4 David born Starts too late 1036 and count accession years 1035 1034 Daniel , Ezra , Haggai and Zechariah , and the 1033 Babylonian interpolation at Jeremiah 52:28–30 , use 1032 Nisan-based dating and do not count accession Nabu-shum-libur 1031 years 1030 1029 Ezekiel counts Tishri-based years of exile 1028 Ages shown are for the king whose reign begins 1 Samuel 13:1 Saul’s reign begins 1027 1 that year; ages are ordinal, i.e. -

Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah As Seen Through the Assyrian Lens

Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah as Seen Through the Assyrian Lens: A Commentary on Sennacherib’s Account of His Third Military Campaign with Special Emphasis on the Various Political Entities He Encounters in the Levant Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Paul Downs, B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Sam Meier, Advisor Dr. Kevin van Bladel Copyright by Paul Harrison Downs 2015 2 Abstract In this thesis I examine the writings and material artifacts relevant to Sennacherib’s third military campaign into the regions of Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah. The intent of this examination is to investigate the political, ethnic, and religious entities of the ancient Levant from an exclusively Assyrian perspective that is contemporary with the events recorded. The focus is to analyze the Assyrian account on its own terms, in particular what we discover about various regions Sennacherib confronts on his third campaign. I do employ sources from later periods and from foreign perspectives, but only for the purpose of presenting a historical background to Sennacherib’s invasion of each of the abovementioned regions. Part of this examination will include an analysis of the structural breakdown of Sennacherib’s annals (the most complete account of the third campaign) to see what the structure of the narrative can tell us about the places the Assyrians describe. Also, I provide an analysis of each phase of the campaign from these primary writings and material remains. -

The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 7-1984 The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom Wayne Brindle Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Brindle, Wayne, "The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom" (1984). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 76. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom Wayne A. Brinale Solomon's kingdom was undoubtedly the Golden Age of Israel. The accomplishments of Solomon and the highlights of his reign include those things which all kings and empires sought, and most did not obtain. A prominent feature of Solomon's rule was his preparation for defense. He fortified the key cities which ringed Israel's cen ter: Hazor, Megiddo, Gezer, Beth-horon, and Baalath ( 1 Kings 9:15-19). He assembled as many as 1,400 chariots and 12,000 horsemen, and maintained 4,000 stables in which to house the horses (1 Kings 10:26; 2 Chron. 9:25). And he kept a large standing army, which required enormous amounts of food and other provisions. * Solomon also had a much larger court than David's. He appointed 12 district supervisors ( 1 Kings 4) and as many as 550 supervisors of labor ( 1 Kings 9:23), who were in turn supervised by an overseer of district officers and a prime minister.2 He had 1,000 wives or concubines, and probably had a large number of children. -

Timeline of Lebanese History Year Events

1 Timeline of Lebanese History Year Events -2900 Second wave of Semitic migration, the Canaanites, and the establishment of Sidon and Tyre -2810 In Byblos, the Temple of The Lady of Byblos was built and probably partially financed by the Egyptian Pharaoh -2800 Human habitation existed in the Baalbeck site -2560 The Egyptian Pharaoh Snefru sends a maritime expedition of forty vessels to bring cedar timber -2160 The great migration wave of the Semitic nomadic Amorites overtakes the Phoenician costs -2150 Byblos is destroyed by the first Amorite invasion -2000 The inhabitants of Byblos establish the city of Beirut -2000 The Phoenicians apply the decimal system in their arithmetic -2000 The Phoenicians settle in Baalbeck where they erect the temple dedicated to Baal the sun god -1900 Beginning construction of the Temple of Obelisks in Byblos attesting to the strong Egyptian cultural influence -1440 Introduction of the cult of the Phoenician god Baal into Egypt -1300 The appearance of the perfect Phoenician alphabet of 22 letters of which the Greek, Etruscan, Latin, Indian, and Arabic alphabet shall be derived -1298 The Pharaoh Ramses II arrives at Nahr el-Kalb at the head of his army -1298 Ramses II withdraws to Palestine through the Bekaa following the vague inconclusive ending of the battle of Kadesh -1282 Byblos enjoys its independence keeping very good relations with Egypt, though. -1200 Peoples of the sea raid the Oriental Mediterranean costs 2 -1200 Apart from Sidon which was destroyed by the Philistines, the other Phoenician towns were momentarily evacuated suffering less damage -1186 The Canaanites of the south chased by the Philistines take refuge in the Phoenician towns -1110 The Phoenicians establish the city of Lixus on the Atlantic cost. -

History of King Solomon (1:1-9: 31) Solomon's Kingdom the Temple and Its Furnishings 1

SECOND CHRONICLES LESSON FOURTEEN 1-4 I. THE HISTORY OF KING SOLOMON (1:1-9: 31) SOLOMON'S KINGDOM THE TEMPLE AND ITS FURNISHINGS 1. SOLOMON AT GIBEON (I1 Chronicles, Chapter 1) INTRODUCTION Solomon's choice of wisdom qualified him to be a very effective leader of Israel. He is faithful as he begins to carry out the work that his father, David had committed to him. The details of the Temple and the elaborate appointments for its adornment describe the beauty of this amazing building. ~ TEXT Chapter 1:l. And Solomon the son of David was I strengthened in his kingdom, and Jehovah his God was with I him, and magnified him exceedingly. 2. And Solomon spake I unto all Israel, to the captains of thousands and of hundreds, and to the judges, and to every prince in all Israel the heads of the fathers' houses. 3. So Solomon, and all the assembly with 1 him, went to the high place that was at Gibeon; for there was 1 the tent of meeting of God, which Moses the servant of Jehovah I had made in the wilderness. 4. But the ark of God had David brought up from Kiriath-jearim to the place that David had 1 prepared for it; for he had pitched a tent for it at Jerusalem. 5. ' Moreover the brazen altar, that Bezalel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, had made, was there before the tabernacle of Jehovah: 1 and Solomon and the assembly sought unto it. 6. And Solomon went up thither to the brazen altar before Jehovah, which was at the tent of meeting, and offered a thousand burnt-offerings 1 upon it.