Sign at Your Own Risk-- the “Rca” Prenuptial May Prejudice the Fairness of Your Future Divorce Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

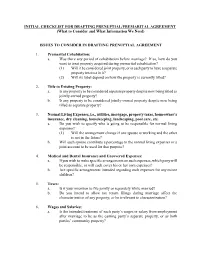

INITIAL CHECKLIST for DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need)

INITIAL CHECKLIST FOR DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need) ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT 1. Premarital Cohabitation: a. Was there any period of cohabitation before marriage? If so, how do you want to treat property acquired during premarital cohabitation? (1) Will it be considered joint property, or is each party to have a separate property interest in it? (2) Will its label depend on how the property is currently titled? 2. Title to Existing Property: a. Is any property to be considered separate property despite now being titled as jointly-owned property? b. Is any property to be considered jointly-owned property despite now being titled as separate property? 3. Normal Living Expenses, i.e., utilities, mortgage, property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, dry cleaning, housekeeping, landscaping, pool care, etc. a. Do you wish to specify who is going to be responsible for normal living expenses? (1) Will the arrangement change if one spouse is working and the other is not in the future? b. Will each spouse contribute a percentage to the normal living expenses or a joint account to be used for that purpose? 4. Medical and Dental Insurance and Uncovered Expenses: a. If you wish to make specific arrangements on such expenses, which party will be responsible, or will each cover his or her own expenses? b. Are specific arrangements intended regarding such expenses for any minor children? 5. Taxes: a. Is it your intention to file jointly or separately while married? b. Do you intend to allow tax return filings during marriage affect the characterization of any property, or be irrelevant to characterization? 6. -

Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2002-2019, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2019 Edition Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut A Guide to Resources in the Law Library Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Current Premarital Agreement Law...................................................... 4 Table 1: Connecticut Premarital Agreement Act: House Debate ........................ 14 Section 2: Postnuptial Agreement Law .............................................................. 15 Section 3: Prior Premarital Agreement Law ........................................................ 22 Table 2: Three Prong Test ............................................................................ 25 Section 4: Premarital Agreement Form and Content .......................................... 26 Section 5: Enforcement and Defenses ............................................................... 32 Table 3: Surveys of State Premarital Agreement Laws ..................................... 40 Section 6: Modification or Revocation ............................................................... 41 Section 7: Federal Tax Aspect .......................................................................... 44 Section 8: State Tax Aspect ............................................................................. 47 Appendix: Legislative Histories in the Connecticut Courts ................................... -

On Organ Donation Aspects of This Issue

time to read and comment upon my Tendler, as well as a committee of the votes are less than fifty percent of the Counterpoint article. He is a forceful, energetic Israeli Chief Rabbinate, do interpret total membership since approximately advocate for the encouragement of Rav Moshe’s pesakim as supporting half of the membership claims to have organ donation within the Orthodox BSD, but certainly none of us can dis- no informed opinion on the matter.) community, and HODS’ web site is a miss out of hand the contrary interpre- III. Views of other posekim: Brain-death treasure-trove of valuable information tation of Rav Auerbach, Rav Elyashiv criteria have been rejected by a whole on both the medical and halachic and Rav Soloveichik. For further eluci- spate of posekim including Rav Auerbach, On Organ Donation aspects of this issue. Indeed, I cited dation, I refer the reader to my earlier Rav Elyashiv, Rav Waldenberg, Rav this source several times in my article. article, “The Brain Death Controversy Yitzchok Weiss, Rav Nissan Karelitz, Rav I realize, as well, that he and his orga- in Jewish Law,” Jewish Action (spring Yitzchok Kolitz, Rav Shmuel Wozner, Rav nization are motivated solely out of 1992): 61 (available at the HODS web Ahron Soloveichik, Rav Hershel Schachter I commend Rabbi Breitowitz’s and documents from these rabbis may sides of the BSD debate, and therefore concern for those persons who desper- site) and especially the addendum in and Rabbi J. David Bleich. Some of these attempt to expound upon the complicat- be found at the web site of the we offer a unique organ donor card ately need organs to stay alive. -

By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation Agreements Create

“Sweetheart Deals in High Demand” By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation agreements create rights and obligations for unmarried couples. Arlene G. Dubin, a partner at Moses & Singer, writes that many people think of cohabitation agreements as the same as prenuptial agreements, but without the “nup.” But there are important distinctions: living together agreements have no specific statutory requirements and are governed by contract principles; and there are potential tax issues not presented by prenups. Unmarried couples made up 12 percent of U.S. couples in 2010, a 25 percent increase in 10 years, according to a recently released U.S. census report.1 The result has been a corresponding surge in the demand for cohabitation or living together agreements. “Cohabs” are fast becoming as popular as “prenups,” and thus an increasingly important part of family law practice. Cohabitation has increased for many reasons. An oft-cited practical reason is the reduction of household expenses. Cohabitation is widely accepted and promoted via celebrity role models, such as Governor Andrew Cuomo and Sandra Lee, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, and Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell. An astounding 40 percent of U.S. adults say they have lived with a partner without the benefit of marriage.2 Cohabitation is often a stepping stone for parties headed for marriage. Studies have found that more than 70 percent of couples who marry today lived together first.3 And often it is a choice for older couples who do not want to upset their family or friends or lose Social Security or other benefits. -

Neuerwerbungsliste Theologie Juni 2007

Neuerwerbungsliste der Seminarbibliothek Theologische Fakultät Juni 2007, geordnet nach Signaturen Allgemeines zu Theologie und Bibel Ba 155<138> Creator est Creatura : Luthers Christologie als Lehre von der Idiomenkommunikation / hrsg. von Oswald Bayer ... - Berlin [u.a.] : de Gruyter, 2007. - XIII, 323 S. (Theologische Bibliothek Töpelmann ; 138) Überw. in dt. Sprache, ein Kapitel engl. ISBN - 978-3-11-019276-6 Ba 194 I<1,1,1/5> Vetus Latina : die Reste der altlateinischen Bibel / nach Petrus Sabatier neu gesammelt und hrsg. von der Erzabtei Beuron unter der Leitung von Roger Gryson 1,1: Répertoire général des auteurs ecclésiastiques latins de l'antiquité et du haut moyen âge / Roger Gryson T. 1: Introduction. Répertoire des auteurs: A - H. - 5. éd. mise à jour du "Verzeichnis der Sigel für Kirchenschriftsteller" commencé par Bonifatius Fischer, continué par Hermann Josef Frede. - Freiburg : Herder, 2007. - 575 S. Vorw. und Einf. in dt. und franz. Sprache ISBN - 978-3-451-00134-5 Ba 194 I<1,1,2/5> Vetus Latina : die Reste der altlateinischen Bibel / nach Petrus Sabatier neu ges. und hrsg. von der Erzabtei Beuron unter der Leitung von Roger Gryson 1,1: Répertoire général des auteurs ecclésiastiques latins de l'antiquité et du haut moyen âge / Roger Gryson T. 2: Répertoire des auteurs: I - Z. Auteurs sans sigle propre. Tables. - 5. éd. mise à jour du "Verzeichnis der Sigel für Kirchenschriftsteller" commencé par Bonifatius Fischer, continué par Hermann Josef Frede. - Freiburg : Herder, 2007. - S. 581 - 1085. ISBN - 978-3-451-00137-6 Ba 240<61> Matthew and his world : the gospel of the open Jewish Christians ; studies in biblical theology / Benedict T. -

Loving the Convert Prior to a Completed Conversion: with a Test Case Application of Inviting Conversion Candidates to Pesach Seder and Yom Tov Meals

147 Loving the Convert Prior to a Completed Conversion: With a Test Case Application of Inviting Conversion Candidates to Pesach Seder and Yom Tov Meals By: MICHAEL J. BROYDE and BENJAMIN J. SAMUELS Introduction The Torah enjoins us numerous times concerning the mitzvah of Ahavat ha-Ger,1 which literally means the love of the stranger or sojourner, though is primarily understood in Jewish legal sources to refer more specifically to loving the convert to Judaism.2 Furthermore, the Torah commands us that “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), and also charges us to love God (Deuteronomy 6:4), creating multiple duties of love as halakhic obligations. This article will explore the question: When does the duty to love the convert commence and does it impact the con- version process? Does it apply only to a newly converted Jew, or to a Noahide who is in the process of converting, or even to a Gentile who has expressed an interest in converting? The process of conversion to Judaism can be divided into three fun- damental stages: In the first stage, the person makes a personal decision 1 See Leviticus 19:34; Deuteronomy 10:18-19. The Torah also prohibits oppress- ing the convert, “lo toneh” and “Lo tonu”—see Exodus 22:20; Leviticus 19:33; TB Bava Metzia 58b, 59b, and Ben Zion Katz, “Don’t Oppress the Ger,” Seforim Blog <https://seforimblog.com/2019/07/dont-oppress-the-ger/>. However, this article will not investigate the question of when the prohibition against oppressing a convert begins, which may or may not track in parallel with the mitzvah of Ahavat ha-Ger. -

******Winter Pdf Page

“the comforter.” All his life, my father quence quelled the rebellion, and he when it was my father’s turn to drive, Working with his close friend, Eliyahu kept a framed photograph of the Imrei remained in Danville for three more he was determined to get the children Kitov, he translated two of Kitov’s clas- Emes on his desk. years. Many of his congregants became to school on time, despite a terrible sic books, A Jew and His Home and The lifelong friends and loyalists. A surpris- pain in his side. In Norfolk, my father Book of Our Heritage. My father’s final ing number of Danville children were collapsed with what proved to be a resting place is on Har HaMenuchos, “Daddy, tell us again about inspired by my father to pursue careers ruptured appendix. The other father near that of his beloved friend. the shtetl where you grew up,” my sib- in kiruv, chinuch and the rabbinate. made no more threats, and all his chil- My youngest brother was born just lings and I used to joke. We knew our After leaving Danville, my father dren grew up to build Torah-true before the Six Day War, and soon after father was American-born, and he spoke served as YU’s mashgiach ruchani (spiri- homes. that my father became the rabbi of the English eloquently. Yet there was always tual advisor) for a short time. My father The following year, my father started Young Israel of Far Rockaway, a post something of the foreigner about him. ultimately moved away from the YU a day school in Newport News. -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression & -

Convention Program

Convention Program The 48th Annual Convention of The Rabbinical Council of America April 29th - May 1st 2007 Museum of Jewish Heritage Battery Place, New York, NY Concluding with Parallel Yemei Iyyun at The Wilf Campus, Yeshiva University The Orthodox Union The Center for Jewish History Rabbi Daniel Cohen Chairman Convention Program Tearoom: Sunday/Monday 2.00pm – 5.00pm in the Events Hall Time Sunday Events Sunday 1-3pm RCA Executive Committee Meeting Sunday 2pm Convention Registration Sunday 3pm Opening Keynote Plenary Welcoming Remarks Rabbi Daniel Cohen, Convention Committee Chairman The Rabbi’s Pivotal Leadership Role in Energizing the Future of American Jewish Life Richard Joel, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Orthodox Union Edmond J. Safra Hall Sunday 4 PM Talmud Torah Track Leadership Track Networking Track Part 1 Prophetic Leadership: Guided Workshop: Forget the Lone Ranger: Yirmiyahu as a Man of Emet in a Finding Your Leadership Style Best Networking Practices Within World of Sheker and Maximizing your Personal and Beyond the Synagogue. Rabbi Hayyim Angel, Power within your Shul Chairman: Rabbi David Gottlieb, Cong. Shearith Israel, NY Dr. David Schnall, Shomrei Emunah, Baltimore MD Azrieli Graduate School of Rabbi Reuven Spolter, Jewish Education and Young Israel of Oak Park Administration Rabbi Kalman Topp, YI of Woodmere Shomron Yehudah Chevron Sunday 5 PM Talmud Torah Track Leadership Track Networking Track Part 2 Communication or An IDF Officer’s Leadership Best Networking Practices Excommunication?: An Analysis Insights as Related to the Rabbi Eli Weinstock, of Two Rabbinic Policies Contemporary Rabbinate Cong. Kehilath Jeshurun, NY. Prof. Yaakov Elman, Rabbi Binny Friedman, Rabbi Ari Perl, Congregation Bernard Revel Graduate School Isralight Shaare Tefilla, Dallas TX Rabbi Chaim Marder, Hebrew Institute, White Plains, NY Shomron Yehudah Chevron Sunday 6 PM Mincha Edmond J. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

HARAV GEDALIA DOV SCHWARTZ, ZT”L by Rabbi Shaanan Gelman

HARAV GEDALIA DOV SCHWARTZ, ZT”L By Rabbi Shaanan Gelman On December 9, 2020 the Chicago Jewish Community lost Kidushin (33b) describes another show of respect shown one of its greatest leaders. Rav Gedalia Dov Schwartz zt”l to the Av Beth Din when he is outside of the study hall, came to Chicago as the Av Beth Din of the cRc, the Chief presumably in the marketplace: Justice of our rabbinical court, and the highest authority אב ב”ד עובר עומד מלפניו מלא עיניו וכיון שעבר ד' אמות יושב for matters of Jewish law and tradition. He was recognized internationally as a posek and was renowned for his immense If an Av Beth din passes by one stands up in his presence as soon expertise and broad knowledge. Since his arrival in Chicago in as he is within range of vision, and once he passes four cubits from 1986, Rav Schwartz established himself as a leading light for him, one may sit. the broader community, a mentor and supporter of Rabbis Chazal saw these two halachot as part of the same principle, ִמ ְּפ ֵני ֵ ׂש ָיבה ָּתקוּם ְו ָה ַד ְר ָּת ְּפ ֵני ָז ֵקן around the country, and a cherished guide for the countless a fulfilment of the commandment of individuals who sought his sage counsel. – yet they also understood that the reality inside of the study The Gemara dictates two halachot regarding giving respect to hall or the academy was entirely different from the world the Av Beth Din. Tractate Horayot (13b) describes the honor outside. -

From the Rabbi's Desk: Rabbi Chaim Zev Malinowitz's Emails

From the Rabbi’s Desk: Rabbi Chaim Zev Malinowitz’s Emails SAMPLE Edited by: Eliezer Brodt Ramat Beit Shemesh 2020 Introduction: Within hours of the Petirah of the Rav, Rabbi Chaim Zev Malinowitz Zt”l, I began putting my memories of the Rav down on paper. Among many other facets of the Rav, I wrote about his relationship to email. I was, and still am, fascinated at the extent that the Rav communicated via email. Despite the fact that he was not especially computer-savvy, the Rav embraced using email from the time that the technology first became available. Among the reasons that the Rav preferred email to in-person conversation was because it gave him time to think about the questions that were sent to him, thus fulfilling .והוי מותנים בדין the mishna in Avot In addition, the Rav understood the power of the written word over speech (see the Rambam who says that when one writes, one has to be much more careful than when he speaks, since the impact is so much greater), and he hoped people would read his thought-out, and at times humorous and witty, answers carefully. Being Chief Editor of the Artscroll Shas (and much more) he had lots of experience in writing clearly and to the point. I would like to emphasize, however, that the Rav was not an ‘SMS Rabbi’ in any sense, as is evident from his extensive responses. Moreover, when he couldn’t convey something clearly via email, he would tell the person with whom he was corresponding to call him.