The Case Study of Iraqi Kurdistan. This Research Enables the Nation Brand to Be an Analytical Framework Adapted to the Context of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeology of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Adjacent Regions

Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. The Archaeology of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Adjacent Regions Edited by Konstantinos Kopanias and John MacGinnis Archaeopress Archaeology Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 393 9 ISBN 978 1 78491 394 6 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2016 Cover illustration: Erbil Citadel, photo Jack Pascal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. Contents List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................iv Authors’ details ..................................................................................................................................... xii Preface ................................................................................................................................................. xvii Archaeological investigations on the Citadel of Erbil: Background, Framework and Results.............. 1 Dara Al Yaqoobi, Abdullah Khorsheed Khader, Sangar Mohammed, Saber -

THE VEPSIAN ECOLOGY CHALLENGES an INTERNATIONAL PARADIGM Metaphors of Language Laura Siragusa University of Tartu

ESUKA – JEFUL 2015, 6–1: 111–137 METAPHORS OF LANGUAGE: THE VEPSIAN ECOLOGY CHALLENGES AN INTERNATIONAL PARADIGM Metaphors of language Laura Siragusa University of Tartu Abstract. At present Veps, a Finno-Ugric minority in north-western Russia, live in three different administrative regions, i.e., the Republic of Karelia, and the Leningrad and Vologda Oblasts. Due to several socio-economic and political factors Veps have experienced a drastic change in their communicative practices and ways of speaking in the last century. Indeed, Vepsian heritage language is now classifi ed as severely endangered by UNESCO. Since perestroika a group of Vepsian activists working in Petrozavodsk (Republic of Karelia) has been promoting Vepsian language and culture. This paper aims to challenge an international rhetoric around language endangerment and language death through an analysis of Vepsian language ecology and revitalisation. Vepsian ontologies and communicative practices do not always match detached meta- phors of language, which view them as separate entities and often in competition with each other. The efforts to promote the language and how these are discussed among the policy-makers and Vepsian activists also do not concur with such a drastic terminology as death and endangerment. Therefore, this paper aims to bring to the surface local ontologies and worldviews in order to query the paradigms around language shift and language death that dominate worldwide academic and political discourse. Keywords: Vepsian, language endangerment, death and revival, metaphor of a language, heritage language, ways of speaking, communicative practices DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2015.6.1.07 1. Introduction Veps, a Finno-Ugric minority in the Russian Federation, live in three different administrative regions of north-western Russia (namely, the Republic of Karelia, and the Leningrad and Vologda Oblasts) (Strogal’ščikova 2008). -

The Future of the Caucasus After the Second Chechen War

CEPS Working Document No. 148 The Future of the Caucasus after the Second Chechen War Papers from a Brainstorming Conference held at CEPS 27-28 January 2000 Edited by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci July 2000 A Short Introduction to the Chechen Problem Alexandru Liono1 Abstract The problems surrounding the Chechen conflict are indeed many and difficult to tackle. This paper aims at unveiling some of the mysteries covering the issue of so-called “Islamic fundamentalism” in Chechnya. A comparison of the native Sufi branch of Islam and the imported Wahhaby ideology is made, in order to discover the contradictions and the conflicts that the spreading of the latter inflicted in the Chechen society. Furthermore, the paper investigates the main challenges President Aslan Maskhadov was facing at the beginning of his mandate, and the way he managed to cope with them. The paper does not attempt to cover all the aspects of the Chechen problem; nevertheless, a quick enumeration of other factors influencing the developments in Chechnya in the past three years is made. 1 Research assistant Danish Institute of International Affairs (DUPI) 1 1. Introduction To address the issues of stability in North Caucasus in general and in Chechnya in particular is a difficult task. The factors that have contributed to the start of the first and of the second armed conflicts in Chechnya are indeed many. History, politics, economy, traditions, religion, all of them contributed to a certain extent to the launch of what began as an anti-terrorist operation and became a full scale armed conflict. The narrow framework of this presentation does not allow for an exhaustive analysis of the Russian- Chechen relations and of the permanent tensions that existed there during the known history of that part of North Caucasus. -

Non-State Nations in International Relations: the Kurdish Question Revisited

2018 Non-State Nations in International Relations: The Kurdish Question Revisited RESEARCH MASTERS WITH TRAINING – THESIS SUBMISSION JESS WIKNER 1 Statement of Declaration: I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. 2 Abstract This thesis explores the fundamental research puzzle of why non-state nations struggle to achieve independent sovereign statehood through secession. It explores why non-state nations like the Kurds desire sovereign statehood, and why they fail to achieve it. This thesis argues two main points. Firstly, non-state nations such as the Kurds seek sovereign statehood because of two main reasons: the essence of nationhood and national self-determination is sovereign statehood; and that non-state nations are usually treated unfairly and unjustly by their host state and thus develop a strong moral case for secession and sovereign statehood. Secondly, non-state nations like the Kurds fail to achieve sovereign statehood mainly because of key endogenous and exogenous factors. The endogenous factors comprise internal divisions which result in failure to achieve a unified secessionist challenge, due to differences in factions which result in divergent objectives and perspectives, and the high chances of regime co-optation of dissident factions. Exogenous factors include the international normative regime which is unsupportive of secession, hence non-state nations like the Kurds do not receive support from the UN and other global bodies in their quest for sovereign statehood; and that non-state nations also seldom receive the backing from Major Powers, both democratic and non-democratic, in their efforts to secede from their host state and set up their own sovereign state. -

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq

WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ Contents President Masoud Barzani 2 Fast facts about the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 3 Overview of the Kurdistan Region 4 Key historical events through the 19th century 9 Modern history 11 The Peshmerga 13 Religious freedom and tolerance 14 The Newroz Festival 15 The Presidency of the Kurdistan Region 16 Structure of the KRG 17 Foreign representation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 20 Kurdistan Region - an emerging democracy 21 Focus on improving human rights 23 Developing the Region’s Energy Potential 24 Kurdistan Region Investment Law 25 Tremendous investment opportunities beckon 26 Tourism potential: domestic, cultural, heritage 28 and adventure tourism National holidays observed by 30 KRG Council of Ministers CONTENTS Practical information for visitors to the Kurdistan Region 31 1 WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ President Masoud Barzani “The Kurdistan Region of Iraq has made significant progress since the liberation of 2003.Through determination and hard work, our Region has truly become a peaceful and prosperous oasis in an often violent and unstable part of the world. Our future has not always looked so bright. Under the previous regime our people suffered attempted We are committed to being an active member of a federal, genocide. We were militarily attacked, and politically and democratic, pluralistic Iraq, but we prize the high degree of economically sidelined. autonomy we have achieved. In 1991 our Region achieved a measure of autonomy when Our people benefit from a democratically elected Parliament we repelled Saddam Hussein’s ground forces, and the and Ministries that oversee every aspect of the Region’s international community established the no-fly zone to internal activities. -

The Multicultural Moment

Mats Wickström View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Multicultural provided by National Library of Finland DSpace Services Moment The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, Mats Wickström 1964–1975 Mats Wickström | The Multicultural Moment | 2015 | Wickström Mats The studies in this compilation thesis examine the origins The Multicultural Moment and early post-war history of the idea of multiculturalism as well as the interplay between idea and politics in The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in the shift from a public ideal of homogeneity to an ideal Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, 1964–1975 of multiculturalism in Sweden. The thesis shows that ethnic activists, experts and offi cials were instrumental in the establishment of multiculturalism in Sweden, as they also were in two other early adopters of multiculturalism, Canada and Australia. The breakthrough of multiculturalism, such as it was within the limits of the social democratic welfare-state, was facilitated by who the advocates were, for whom they made their claims, the way the idea of multiculturalism was conceptualised and legitimised as well as the migratory context. 9 789521 231339 ISBN 978-952-12-3133-9 Mats Wikstrom B5 Kansi s16 Inver260 9 December 2014 2:21 PM THE MULTICULTURAL MOMENT © Mats Wickström 2015 Cover picture by Mats Wickström & Frey Wickström Author’s address: History Dept. of Åbo Akademi -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Transformation of Erbil Old Town Fabric Asmaa Ahmed Mustafa Jaff

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 10, Issue 3, March-2019 443 ISSN 2229-5518 Transformation of Erbil Old Town Fabric Asmaa Ahmed Mustafa Jaff Abstract— The historical cities in a time change with different factors. Like population growth, economical condition, social unconscious as can be listed many reasons. Erbil the capital located in the north of Iraq, a historic city. The most important factor in the planning and urban development of the city, and it was the focus point in the radial development of the city and iconic element is old town Erbil was entered on the World Heritage Sites (UNESCO) in 2014. In order to preserve and rehabilitation of the old historical city and conservation this heritage places and transfer for future generation and to prevent the loss of the identity of the city. This research focusing on the heritage places in the city and historical buildings, identifying the city, also the cultural and architectural characteristic. Cities are a consequence of the interaction of cultural, social, economic and physical forces. Countries have to adapt to these social, economic, physical and cultural changes, urban problems in order to meet the new needs and urban policies. Urban transformations, economic activity, social urban spaces that have lost their functions and physical qualities. This thesis study reveals the spatial and socio-economic effects of urban transformation. Historical Erbil city, which is the urban conservation project, was selected as the study area and the current situation, spatial and socio-economic effects of the urban transformation project being implemented in this region were evaluated. -

Separatist Movements Should Nations Have 2 a Right to Self-Determination? Brian Beary

Separatist Movements Should Nations Have 2 a Right to Self-Determination? Brian Beary ngry protesters hurling rocks at security forces; hotels, shops and restaurants torched; a city choked by teargas. AThe violent images that began flashing around the world on March 14 could have been from any number of tense places from Africa to the Balkans. But the scene took place high in the Himalayas, in the ancient Tibetan capital of Lhasa. Known for its red-robed Buddhist monks, the legendary city was the latest flashpoint in Tibetan separatists’ ongoing frustra- tion over China’s continuing occupation of their homeland.1 Weeks earlier, thousands of miles away in Belgrade, Serbia, hun- dreds of thousands of Serbs took to the streets to vent fury over Kosovo’s secession on Feb. 17, 2008. Black smoke billowed from the burning U.S. Embassy, set ablaze by Serbs angered by Washington’s acceptance of Kosovo’s action.2 “As long as we live, Kosovo is Serbia,” thundered Serbian 3 AFP/Getty Images Prime Minister Vojislav Kostunica at a rally earlier in the day. The American Embassy in Belgrade is set ablaze on Kosovo had been in political limbo since a NATO-led military Feb. 21 by Serbian nationalists angered by U.S. force wrested the region from Serb hands in 1999 and turned it support for Kosovo’s recent secession from Serbia. into an international protectorate after Serbia brutally clamped About 70 separatist movements are under way down on ethnic Albanian separatists. Before the split, about 75 around the globe, but most are nonviolent. -

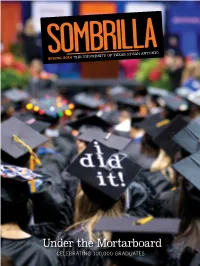

Under the Mortarboard

SombrillaSPRING 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT SAN ANTONIO Under the Mortarboard CELEBRATING 100,000 G RADUATES ON THE COVER: One of the thousands of recent UTSA graduates dis- plays her excitement on her mortarboard at the fall 2013 ceremony. COVER PHOTO: MARK MCCLENDON ON THIS PAGE: Students celebrate at the fall 2013 commencement. © EDWARD A. ORNELAS/SAN ANTONIO EXPRESS-NEWS/ZUMAPRESS.COM inSiDe Kicking It A simulator designed by UTSA students boils 12 down the science of football’s perfect kick. Under the Mortarboard Decorating mortarboards has become an unofficial highlight of commencement. As UTSA celebrates 100,000 graduates, meet the individuals behind some of the ceremony’s 16 unique mortarboard stories. Saving the Past In Iraq, two UTSA professors have joined 24 the effort to preserve ancient sites. The PaSeo CommuniTy TEACHING LET THE WORD 28 BIG UNIVERSITY’S 4 OUR FUTURE 8 GO FORTH SMALL START The teachers and Professor Ethan Get to know a few of faculty at Forester Wickman turns a the first to graduate Elementary exem- president’s words in 1974. plify the education into music. pipeline. 30 TRUCKIN’ 10 LET’S CIRCLE It TOMATO UNLOCKING One San Antonio UTSA alum Shaun 6 THE CLOUD middle school is Lee brings the farm- Cutting-edge tech- working with UTSA ers market to you. nologies come and UT Austin to UTSA. to change how 31 CLASS NOTES students are disci- Profile of commu- 7 ROWDY CENTS plined. nication studies Students can learn trailblazer Dariela money manage- ROADRUNNER Rodriguez ’00, M.A. ment techniques 14 SPORTS ’08; and Generations with this free Sports briefs; plus Federal Credit Union program. -

NORTH AMERICAN FINNS in SOVIET KARELIA 1921-1938 Kitty

Revista Română pentru Studii Baltice şi Nordice, Vol. 2, Issue 2, 2010, pp. 203-224 ORGING A SOCIALIST HOMELAND FROM MULTIPLE WORLDS: NORTH F AMERICAN FINNS IN SOVIET KARELIA 1921-1938 Kitty Lam Michigan State University, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In the early 1930s, the Soviet Union recruited an estimated 6,000 Finns from North America to augment the number of skilled workers in the recently established Karelian Autonomous Republic. Using migrants' letters and memoirs held at the Immigration History Research Center, this essay examines how these North American Finns adapted and responded to fluctuating policies in the Soviet Union that originally flaunted the foreign workers as leaders in the Soviet modernization drive and as the vanguard for exporting revolution, but eventually condemned them as an enemy nation to be expunged. It also analyzes the extent to which these immigrants internalized 'building socialism' as part of their encounter with Soviet Karelia. Such an exploration requires assessing how these settlers’ ideological adaptation affected their experiences. This paper argues that by placing the North American Finns’ experience in the wider context of Soviet state building policies, these migrants’ identity formation involved participation in, avoidance of, and opposition to the terms of daily life that emerged within the purview of building socialism. Rezumat: La începutul anilor ’30, Uniunea Sovietică a recrutat un număr estimat la 6.000 de finlandezi din America de Nord pentru a mări numărul de muncitori calificaţi -

The Role of the Republic of Karelia in Russia's Foreign and Security Policy

Eidgenössische “Regionalization of Russian Foreign and Security Policy” Technische Hochschule Zürich Project organized by The Russian Study Group at the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research Andreas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic,´ Andrei Makarychev, Oleg Alexandrov WORKING PAPER NO.5 MARCH 2001 The Role of the Republic of Karelia in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy DESIGN : SUSANA PERROTTET RIOS This paper gives an overview of Karelia’s international security situation. The study By Oleg B. Alexandrov offers an analysis of the region’s various forms of international interactions and describes the internal situation in the republic, its economic conditions and its potential for integration into the European or the global economy. It also discusses the role of the main political actors and their attitude towards international relations. The author studies the general problem of center-periphery relations and federal issues, and weighs their effects on Karelia’s foreign relations. The paper argues that the international contacts of the regions in Russia’s Northwest, including those of the Republic of Karelia, have opened up opportunities for new forms of cooperation between Russia and the EU. These contacts have en- couraged a climate of trust in the border zone, alleviating the negative effects caused by NATO’s eastward enlargement. Moreover, the region benefits economi- cally from its geographical situation, but is also moving towards European standards through sociopolitical modernization. The public institutions of the Republic