Non-Timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in Michigan's Upper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweetener Buying Guide

Sweetener Buying Guide The intent of this guide is purely informational. The summaries included represent the highlights of each sweetener and are not meant to be comprehensive. The traffic light system is not a dietary recommendation but a buying guideline. Sugar, in any form (even honey, maple syrup and dried fruit), can suppress the immune system and throw our bodies out of balance. It is important to consume sugar smartly. Start by choosing the best sweeteners for you. Then keep in mind that sugar is best reduced or avoided when your immune system is compromised e.g. - if you have candida overgrowth, are chronically stressed, fatigued or in pain, are diabetic or pre-diabetic, have digestive issues (IBS, Crohn’s etc.), etc... For more detailed information on how sweeteners can affect your body speak to one of our expert nutritionists on staff! The Big Carrot is committed to organic agriculture and as such prioritizes the organic version of all of these products. The organic logo is used below to represent those items that must be organic to be included, without review, on our shelves and in our products. Sweetener Definition Nutrition (alphabetical) Agave is a liquid sweetener that has a texture and appearance similar to honey. Agave Agave contains some fiber and has a low glycemic index syrup comes from the blue agave plant, the same plant that produces tequila, which grows compared to other sweeteners. It is very high in the Agave primarily in Mexico. The core of the plant contains aguamiel, the sweet substance used to monosaccharide fructose, which relies heavily on the produce agave syrup. -

Cusk Fishing Devices, Which Revealed Fish Swimming 20 Freshwater Fish in New Are Heavy Baited Lines Teth- Feet Beneath Us

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 42 MARCH 24, 2011 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Play Ball: Catch-M-All: Kennett High School Two local fishermen embark contributing writer on yearlong quest to catch Shawn Beattie previews and eat every species of 2011 KHS Baseball freshwater fish in N.H… A4 season … A2 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Page Two Play Ball! A look into the 2011 baseball season at Kennett High School By Shawn Beattie and experience that the Eagles Kennett High School possess allow them to move Special to the Mountain Ear people around on defense and give guys rest, while maintain- AMERICA’S PAST TIME ing a strong team from game has returned. Major League to game. Baseball’s spring training has The Eagles did lose veteran been taking place for the past leaders like Jeff Sires and Mike couple of weeks as teams have Larson to graduation but lead- been playing exhibition games ership may not be an issue for in the Southern region of the the team. “As I’ve gone United States. As the snow through high school I have continues to slowly melt here realized every year that as a in New Hampshire, student player your responsibility athletes at Kennett High changes. Your team depends School begin packing their on you as a leader and a play- skis and sneakers away and er. I feel like I have been able dusting off their bats and to grow as an athlete both gloves. A large number of mentally and physically,” said boys gathered in the Kennett Jacobs. -

40 Pelatihan Teknologi Akuaponik Sebagai Solusi

ISSN 2088-2637 Jurnal Pengabdian Dinamika, Edisi 6 Volume1_November 2019 PELATIHAN TEKNOLOGI AKUAPONIK SEBAGAI SOLUSI PENDUKUNG KETAHANAN PANGAN DESA BABADSARI, KABUPATEN PANDEGLANG, BANTEN Rida Oktorida Khastini1) , Aris Munandar2) 1)Jurusan Pendidikan Biologi, Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa 2)Jurusan Perikanan, Fakultas Pertanian, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa e-mail : [email protected] Abstrak Salah satu cara untuk meningkatkan kesejahteraan masyarakat di Desa Babadsari, adalah dengan memberdayakan masyarakatnya dengan mengoptimalkan potensi daerahnya. Lahan pekarangan yang luas dapat dimanfaatkan sebagai sumber yang dapat menunjang ketahanan pangan dalam aspek sosial, ekologi, dan ekonomi bagi rumah tangga maupun masyarakat lokal secara berkelanjutan melalui implementasi teknologi akuaponik. Tujuan program ini adalah dalam rangka meningkatkan pengetahuan masyarakat melalui pelatihan teknologi akuaponik sebagai solusi pendukung ketahanan pangan, serta mengembangkan kegiatan ekonomi produktif masyarakat sebagai bentuk pemberdayaan masyarakat desa. Metode pelaksanaan pelatihan teknologi akuaponik dilakukan dengan 5 tahapan, yaitu tahap persiapan, sosialisasi, pelatihan, pendampingan dan evaluasi. Hasil kegiatan pelatihan teknologi akuaponik di desa Babadsari mendapat respon yang positif dan antusiasme kelompok sasaran. Seluruh peserta merasakan banyak manfaat dari segi estetika dan ekonomi Kegiatan ini memotivasi warga lainnya yang mulai tertarik untuk ikut serta menerapkan teknologi akuaponik di pekarangan rumah mereka sendiri. Warga yang telah menerapkan program tidak lagi membeli beberapa jenis sayur dan ikan ke pasar. Kata kunci: Akuaponik, Babadsari, Ikan, Sayuran Abstract [Aquaponics Technology Training as a solution to support Food Security in Babadsari Village, Pandeglang Regency, Banten]. One way to improve the welfare of the community in Babadsari Village is by empowering the community through optimizing the potential of the area. -

Company Overview

Gilead Sciences Advancing Therapeutics. Improving Lives. Company Overview Gilead Sciences, Inc. is a research-based biopharmaceutical Key Moments in Our History company that discovers, develops and commercializes innovative medicines in areas of unmet medical need. With each new 1987 Gilead founded discovery and investigational drug candidate, we seek to improve AmBisome® approved (Europe) the care of patients living with life-threatening diseases around the 1990 world. Gilead’s therapeutic areas of focus include HIV/AIDS, liver 1991 Nucleotides in-licensed from diseases, cancer and inflammation, and serious respiratory and IOCB Rega cardiovascular conditions. 1996 Vistide® approved Our portfolio of 18 marketed 1999 NeXstar acquired; products contains a number Tamiflu® approved of category firsts, including complete treatment regimens 2001 Viread® approved for HIV and chronic hepatitis Hepsera® approved C infection available in once- 2002 daily single pills. Gilead’s 2003 Triangle Pharmaceuticals acquired; portfolio includes Harvoni® Emtriva® approved (ledipasvir 90 mg/sofosbuvir ® ® 400 mg) for chronic hepatitis C, 2004 Macugen , Truvada approved which is a complete antiviral 2006 Atripla®, Ranexa® approved; treatment regimen in a single Corus, Raylo, Myogen acquired tablet that provides high cure ® rates and a shortened course 2007 Letairis approved; Cork, Ireland, Harvoni, Gilead’s once-daily single of therapy for many patients. manufacturing facility acquired tablet HCV regimen. from Nycomed ® 2008 Lexiscan , Viread® for hepatitis B Nearly 30 Years of Growth approved Gilead was founded in 1987 in Foster City, California. Since CV Therapeutics acquired then, Gilead has become a leading biopharmaceutical company 2009 ® with a rapidly expanding product portfolio, a growing pipeline of 2010 Cayston approved; investigational drugs and more than 7,000 employees in offices CGI Pharmaceuticals acquired across six continents. -

How Trees and People Can Co-Adapt to Climate Change Reducing Vulnerability in Multifunctional Landscapes

How trees and people can co-adapt to climate change Reducing vulnerability in multifunctional landscapes EDITORS MEINE VAN NOORDWIJK MINH HA HOANG HENRY NEUFELDT INGRID ÖBORN THOMAS YATICH WORLD AGROFORESTRY CENTRE How trees and people can co-adapt to climate change Reducing vulnerability in multifunctional landscapes EDITORS MEINE VAN NOORDWIJK MINH HA HOANG HENRY NEUFELDT INGRID ÖBORN THOMAS YATICH Citation Van Noordwijk M, Hoang MH, Neufeldt H, Öborn I, Yatich T, eds. 2011. How trees and people can co-adapt to climate change: reducing vulnerability through multifunctional agroforestry landscapes. Nairobi: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). Disclaimer and copyright The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) holds the copyright to its publications and web pages but encourages duplication, without alteration, of these materials for non- commercial purposes. Proper citation is required in all instances. Information owned by others that requires permission is marked as such. The information provided by the Centre is, to the best of our knowledge, accurate although we do not guarantee the information nor are we liable for any damages arising from use of the information. Website links provided by our site will have their own policies that must be honoured. The Centre maintains a database of users although this information is not distributed and is used only to measure the usefulness of our information. Without restriction, please add a link to our website www.worldagroforestrycentre.org on your website or publication. ISBN 978-979-3198-56-9 World Agroforestry Centre United Nations Avenue, Gigiri PO Box 30677, Nairobi 00100, Kenya Tel: +(254) 20 722 4000 Fax: +(254) 20 722 4001 Email: [email protected] www.worldagroforestry.org Southeast Asia Regional Office Jl. -

Homestead Farming in Kerala: a Multi-Faceted Land-Use System Jacob John*

RESEARCH ARTICLE Homestead Farming in Kerala: A Multi-Faceted Land-Use System Jacob John* Abstract: Homestead farming, prevalent in different parts of the world, presents an excellent example of the many systems and practices of agroforestry. The homestead is an operational farm unit in which a number of crops (including tree crops) are grown, along with rearing of livestock, poultry or fish, mainly for the purpose of meeting the farmer’s basic needs. Homesteads or home gardens, with special reference to Kerala, have been enumerated and their key characteristics summarised in this paper. Homestead farming satisfies the requirements of sustainability by being productive, ecologically sound, stable, economically viable, and socially acceptable. However, land- use changes, availability of agricultural labour, and falling commodity prices are major constraints in homestead farming in Kerala. Future strategies to improve homestead farming should aim at watershed-based development with focus on a whole-farm or systems approach; restructuring and refining existing home gardens, and developing sustainable models through a farmer-participatory approach for each agro-ecological zone; forming homestead clusters; creating germplasm registers; bridging the yield gap by improving crop productivity; developing post-harvest technology of home garden products; generating non-farm employment opportunities; promoting and improving rural financial networks; providing essential rural infrastructure; creating coalitions to address policy concerns at all levels; and broadening consumer perspectives. Keywords: Agroforestry, homestead farming, home gardens, Kerala, sustainable agriculture, home gardens in Indian States, home gardens of Kerala, home gardens for sustainable development, constraints in homestead farming, homestead clusters, land-use system. Introduction Homestead farming or home gardening is a historical tradition that has evolved in many tropical countries over a long period of time. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0143022 A1 Wicker Et Al

US 20170143022A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0143022 A1 Wicker et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2017 (54) COMPOSITIONS INCORPORATING AN (52) U.S. Cl. UMLAM FLAVORAGENT CPC ............... A2.3L 27/20 (2016.08); A23L 27/88 (2016.08); A23L 2/56 (2013.01); A23L 2780 (71) Applicant: Senomyx, Inc., San Diego, CA (US) (2016.08); A23L 27/30 (2016.08); A23K 20/10 (2016.05); A23K 50/40 (2016.05); A61K 47/22 (72) Inventors: Sharon Wicker, Carlsbad, CA (US); (2013.01) Tanya Ditschun, San Diego, CA (US) (21) Appl. No.: 14/948,101 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to compositions containing (22) Filed: Nov. 20, 2015 flavor or taste modifiers, such as a flavoring or flavoring agents and flavor or taste enhancers, more particularly, Publication Classification savory (“umami”) taste modifiers, savory flavoring agents (51) Int. Cl. and savory flavor enhancers, for foods, beverages, and other AOIN 25/00 (2006.01) comestible compositions. Compositions comprising an A23K2O/It (2006.01) umami flavor agent or umami taste-enhancing agent in A6 IK 47/22 (2006.01) combination with one or more other food additives, prefer A2.3L 2/56 (2006.01) ably including a flavorant, herb, Spice, fat, or oil, are A23K 50/40 (2006.01) disclosed. US 2017/O 143022 A1 May 25, 2017 COMPOSITIONS INCORPORATING AN tions WO 02/06254, WO 00/63166 art, WO 02/064631, and UMAM FLAVORAGENT WO 03/001876, and U.S. Patent publication US 2003 0232407 A1. The entire disclosures of the articles, patent BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION applications, -

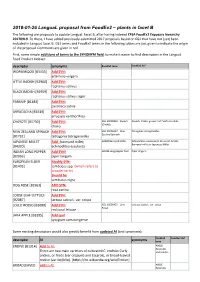

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Journal of Theology of Journal Southwestern dead sea scrolls sea dead SWJT dead sea scrolls Vol. 53 No. 1 • Fall 2010 Southwestern Journal of Theology • Volume 53 • Number 1 • Fall 2010 The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls Peter W. Flint Trinity Western University Langley, British Columbia [email protected] Brief Comments on the Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Importance On 11 April 1948, the Dead Sea Scrolls were announced to the world by Millar Burrows, one of America’s leading biblical scholars. Soon after- wards, famed archaeologist William Albright made the extraordinary claim that the scrolls found in the Judean Desert were “the greatest archaeological find of the Twentieth Century.” A brief introduction to the Dead Sea Scrolls and what follows will provide clear indications why Albright’s claim is in- deed valid. Details on the discovery of the scrolls are readily accessible and known to most scholars,1 so only the barest comments are necessary. The discovery begins with scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in one cave in late 1946 or early 1947 in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about one mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and some eight miles south of Jericho. By 1956, a total of eleven caves had been discovered at Qumran. The caves yielded various artifacts, especially pottery. The most impor- tant find was scrolls (i.e. rolled manuscripts) written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. Almost 900 were found in the Qumran caves in about 25,000–50,000 pieces,2 with many no bigger than a postage stamp. -

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population: 72,752,325 Population 0-14 years: 26% Rural population: 30% Population living under USD 1.25 a day: 2.7% Population living under the national poverty line: 18.1% Income status: Upper middle income economy Ranking: High human development (ranking 92) Per capita total expenditure on health at average exchange rate (US dollar): 571 Life expectancy at birth (years): 73 Healthy life expectancy at birth (years): 62 BACKGROUND INFORMATION The first case of VL in Turkey was reported from Trabzon, in the eastern part of the Black Sea Region, in 1916; the second from Izmir, in the Aegean Region, in 1918. VL is endemic, with sporadic cases reported from 38 of 81 provinces (in 2008, there were less than 10 cases). Most cases occur at the Armenian border, in the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Central Anatolia Regions [1,2]. Dogs seem to be the main animal reservoir with a high seroprevalence of over 20% in some of the endemic regions [3]. CL is caused by L. tropica and is more prevalent in southeastern Anatolia [4], where 96% of cases are located, central Anatolia, the western regions, and, less frequently, in the Mediterranean and Aegean Regions [1,5,6]. In Sanliurfa, southeastern Anatolia, the number of CL cases reported from 1981 to 2000 was 22,335. The reported incidence reached a peak in 1994, with 4,185 cases. There has been a considerable reduction in the number of reported cases from 1995 onwards [7]. A recent upsurge of CL cases in the southeastern Anatolia Region is attributed to the environmental impact of a big irrigation project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi-GAP) [8]. -

Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife Viewing Common Yukon roadside flowers © Government of Yukon 2019 ISBN 987-1-55362-830-9 A guide to common Yukon roadside flowers All photos are Yukon government unless otherwise noted. Bog Laurel Cover artwork of Arctic Lupine by Lee Mennell. Yukon is home to more than 1,250 species of flowering For more information contact: plants. Many of these plants Government of Yukon are perennial (continuously Wildlife Viewing Program living for more than two Box 2703 (V-5R) years). This guide highlights Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 the flowers you are most likely to see while travelling Phone: 867-667-8291 Toll free: 1-800-661-0408 x 8291 by road through the territory. Email: [email protected] It describes 58 species of Yukon.ca flowering plant, grouped by Table of contents Find us on Facebook at “Yukon Wildlife Viewing” flower colour followed by a section on Yukon trees. Introduction ..........................2 To identify a flower, flip to the Pink flowers ..........................6 appropriate colour section White flowers .................... 10 and match your flower with Yellow flowers ................... 19 the pictures. Although it is Purple/blue flowers.......... 24 Additional resources often thought that Canada’s Green flowers .................... 31 While this guide is an excellent place to start when identi- north is a barren landscape, fying a Yukon wildflower, we do not recommend relying you’ll soon see that it is Trees..................................... 32 solely on it, particularly with reference to using plants actually home to an amazing as food or medicines. The following are some additional diversity of unique flora. resources available in Yukon libraries and bookstores. -

Identification of N-Acetyldopamine Dimers from the Dung Beetle Catharsius Molossus and Their COX-1 and COX-2 Inhibitory Activities

Molecules 2015, 20, 15589-15596; doi:10.3390/molecules200915589 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Article Identification of N-Acetyldopamine Dimers from the Dung Beetle Catharsius molossus and Their COX-1 and COX-2 Inhibitory Activities Juan Lu 1,2, Qin Sun 1, Zheng-Chao Tu 3, Qing Lv 2, Pi-Xian Shui 1,* and Yong-Xian Cheng 2,* 1 School of Medicine, Sichuan Medical University, 319 Zhongshan Road, Luzhou 646000, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (Q.S.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Plant Resources in West China, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, China; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 190 Kaiyuan Road, Guangzhou 510530, China; E-Mail: [email protected] * Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.-X.S.); [email protected] (Y.-X.C.); Tel./Fax: +86-871-6522-3048 (Y.-X.C.). Academic Editor: Derek J. McPhee Received: 7 July 2015 / Accepted: 17 August 2015 / Published: 27 August 2015 Abstract: Recent studies focusing on identifying the biological agents of Catharsius molossus have led to the identification of three new N-acetyldopamine dimers molossusamide A–C (1−3) and two known compounds 4 and 5. The structures of the new compounds were identified by comprehensive spectroscopic evidences. Compound 4 was found to have inhibitory effects towards COX-1 and COX-2. Keywords: Catharsius molossus; N-acetyldopamine dimers; COX-1; COX-2 1.