Summer 2021 Sego Lily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies concolor var. concolor White fir Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica Corkbark fir Devender, T. R. (2005) Abronia villosa Hariy sand verbena McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon abutiloides Shrubby Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon berlandieri Berlandier Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon incanum Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon malacum Yellow Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon mollicomum Sonoran Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon palmeri Palmer Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon parishii Pima Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon parvulum Dwarf Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium Abutilon pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon reventum Yellow flower Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia angustissima Whiteball acacia Devender, T. R. (2005); DBGH McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia constricta Whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia greggii Catclaw acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) Acacia millefolia Santa Rita acacia McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia neovernicosa Chihuahuan whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Acalypha lindheimeri Shrubby copperleaf Herbarium Acalypha neomexicana New Mexico copperleaf McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acalypha ostryaefolia McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acalypha pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acamptopappus McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Rayless goldenhead sphaerocephalus Herbarium Acer glabrum Douglas maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer grandidentatum Sugar maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer negundo Ashleaf maple McLaughlin, S. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Taxonomic Novelties from Western North America in Mentzelia Section Bartonia (Loasaceae) Author(S) :John J

Taxonomic Novelties from Western North America in Mentzelia section Bartonia (Loasaceae) Author(s) :John J. Schenk and Larry Hufford Source: Madroño, 57(4):246-260. 2011. Published By: California Botanical Society DOI: 10.3120/0024-9637-57.4.246 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3120/0024-9637-57.4.246 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. MADRON˜ O, Vol. 57, No. 4, pp. 246–260, 2010 TAXONOMIC NOVELTIES FROM WESTERN NORTH AMERICA IN MENTZELIA SECTION BARTONIA (LOASACEAE) JOHN J. SCHENK1 AND LARRY HUFFORD School of Biological Sciences, P.O. Box 644236, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-4236 [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent field collections and surveys of herbarium specimens have raised concerns about species circumscriptions and recovered several morphologically distinct populations in Mentzelia section Bartonia (Loasaceae). From the Colorado Plateau, we name M. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Vascular Flora of West Clear Creek Wilderness, Coconino and Yavapai

VASCULAR FLORA OF WEST CLEAR CREEK WILDERNESS, COCONINO AND YAVAPAI COUNTIES, ARIZONA By Wendy C. McBride A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biology Northern Arizona University May 2016 Approved: Tina J. Ayers, Ph.D., Chair Randall W. Scott, Ph.D. Liza M. Holeski, Ph.D. ABSTRACT VASCULAR FLORA OF WEST CLEAR CREEK WILDERNESS, COCONINO AND YAVAPAI COUNTIES, ARIZONA WENDY C. MCBRIDE West Clear Creek Wilderness bisects the Mogollon Rim in Arizona, and is nested between the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range physiographic provinces. Between 2013 and 2016, a floristic inventory vouchered 542 taxa and reviewed 428 previous collections to produce a total plant inventory of 594 taxa from 93 families and 332 genera. The most species rich families Were Asteraceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, Brassicaceae, Rosaceae, Plantaginaceae, Cyperaceae, and Polygonaceae. Carex, Erigeron, Bromus, Muhlenbergia, and Oenothera Were the most represented genera. Nonnative taxa accounted for seven percent of the total flora. Stachys albens was vouchered as a new state record for Arizona. New county records include Graptopetalum rusbyi (Coconino), Pseudognaphalium pringlei (Coconino), Phaseolus pedicellatus var. grayanus (Coconino), and Quercus rugosa (Coconino and Yavapai). This study quantified and contrasted native species diversity in canyon versus non- canyon floras across the Southwest. Analyses based on eighteen floras indicate that those centered about a major canyon feature shoW greater diversity than non-canyon floras. Regression models revealed that presence of a canyon Was a better predictor of similarity between floras than was the distance betWeen them. This study documents the remarkable diversity found Within canyon systems and the critical, yet varied, habitat they provide in the southwestern U.S. -

Uma Opção Para O Criador Cast

SÃO PAULO• MARÇO/ABRIL/1984 •ANO )(XIV a• a internacional de Cidade Jardim • atos: uma opção para o criador Cast. 1971 , por: Vaguely Noble-Mock Orange, por Dedicate-Alablue, por Blue Larkspur. Coppa d'Oro di Milano, Gr.I-3000m, GP di Milano, Gr .I-2400m (para Star Appeal) e Prix Foy , Gr.III-2400m (para Allez France). 8 terceiros, inclusive: Prêmio Presidente della Republica, Gr.l-2000m, GP di Milano. Gr.l-2400m , GP dei Jockey Club e • Coppa d'Oro, Gr.l-2 400m , Grand Prix de Deauville, Gr.Il-2700m (para Ashmore e Diagramatic), Prix Maurice de Nieuil, Gr.Il-2500 m e Prix Gontaut-Biron, Gr.Ill-2000m V AGUEL Y NOBLE, grande ganhador clássico, é um dos mais destacados reprodutores da atualidade. Pai de inúmeros "stakes winners", incluindo ganhadores de provas de Grupo I na Inglaterra, França, Itália, Irlanda, Alemanha e Estados Unidos. MOCK ORANGE, mãe de 8 ganhadores, sendo 3 ganhadorf's clássicos (Provas de Grupo I, II e III , na Inglaterra, França, Itália e Estados Unidos) é avó, também, de ganhadores clássicos (Provas de Grupo I, na Inglaterra e Estados Unidos), inclusive George Navonod (US$ 350.820, dos 2 aos 4 anos). MOCK ORANGE é irmã materna de ALANESIAN (Best Sprinter da geração USA de 1954), mãe de 8 famosos ~ ganhadores, inc. BOLDNESIAN (Derby Win ner, Classic Sirt>. avô paterno do Tríplice Coroado SEATLE SLEW - J 4 vitórias, US$ 1.208, 726 em 17 corridas) e avó de REVlDERE (8 vitórias. Ganhador de 8 corridas, na Inglaterra, França e Itália, inclusive o US$ 330.0 19, em 11 corridas), elei ta a Melhor Potranca de 3 anu: Prêmio Roma, Gr.I-2800m duas vezes (u ma das quais empatado dos USA, em 1976. -

Jeffrey James Keeling Sul Ross State University Box C-64 Alpine, Texas 79832-0001, U.S.A

AN ANNOTATED VASCULAR FLORA AND FLORISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOUTHERN HALF OF THE NATURE CONSERVANCY DAVIS MOUNTAINS PRESERVE, JEFF DAVIS COUNTY, TEXAS, U.S.A. Jeffrey James Keeling Sul Ross State University Box C-64 Alpine, Texas 79832-0001, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT The Nature Conservancy Davis Mountains Preserve (DMP) is located 24.9 mi (40 km) northwest of Fort Davis, Texas, in the northeastern region of the Chihuahuan Desert and consists of some of the most complex topography of the Davis Mountains, including their summit, Mount Livermore, at 8378 ft (2554 m). The cool, temperate, “sky island” ecosystem caters to the requirements that are needed to accommo- date a wide range of unique diversity, endemism, and vegetation patterns, including desert grasslands and montane savannahs. The current study began in May of 2011 and aimed to catalogue the entire vascular flora of the 18,360 acres of Nature Conservancy property south of Highway 118 and directly surrounding Mount Livermore. Previous botanical investigations are presented, as well as biogeographic relation- ships of the flora. The numbers from herbaria searches and from the recent field collections combine to a total of 2,153 voucher specimens, representing 483 species and infraspecies, 288 genera, and 87 families. The best-represented families are Asteraceae (89 species, 18.4% of the total flora), Poaceae (76 species, 15.7% of the total flora), and Fabaceae (21 species, 4.3% of the total flora). The current study represents a 25.44% increase in vouchered specimens and a 9.7% increase in known species from the study area’s 18,360 acres and describes four en- demic and fourteen non-native species (four invasive) on the property. -

2008 File1lined.Vp

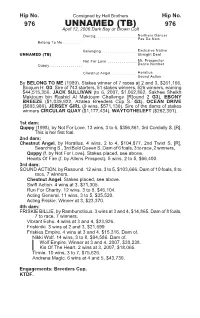

Hip No. Consigned by Hall Brothers Hip No. 976 UNNAMED (TB) 976 April 12, 2006 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Danzig .....................Northern Dancer Pas De Nom Belong To Me .......... Belonging ..................Exclusive Native UNNAMED (TB) Straight Deal Not For Love ...............Mr. Prospector Quppy................. Dance Number Chestnut Angel .............Horatius Sound Action By BELONG TO ME (1989). Stakes winner of 7 races at 2 and 3, $261,166, Boojum H. G3. Sire of 743 starters, 51 stakes winners, 526 winners, earning $44,515,356, JACK SULLIVAN (to 6, 2007, $1,062,862, Sakhee Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum Challenge [R]ound 2 G3), EBONY BREEZE ($1,039,922, Azalea Breeders Cup S. G3), OCEAN DRIVE ($803,986), JERSEY GIRL (9 wins, $571,136). Sire of the dams of stakes winners CIRCULAR QUAY ($1,177,434), WAYTOTHELEFT ($262,391). 1st dam: Quppy (1998), by Not For Love. 13 wins, 3 to 6, $356,861, 3rd Cordially S. [R]. This is her first foal. 2nd dam: Chestnut Angel, by Horatius. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $104,877, 2nd Twixt S. [R], Searching S., 3rd Bold Queen S. Dam of 6 foals, 3 to race, 2 winners, Quppy (f. by Not For Love). Stakes placed, see above. Hearts Of Fire (f. by Allens Prospect). 5 wins, 2 to 5, $66,400. 3rd dam: SOUND ACTION, by Resound. 12 wins, 3 to 5, $103,666. Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, Chestnut Angel. Stakes placed, see above. Swift Action. 4 wins at 3, $71,305. Run For Charity. 12 wins, 3 to 8, $46,104. -

SCATMANDU’S 17 Yearlings Averaged $45,665 at Keeneland September, Fasig-Tipton July & OBS August

ROSADO TAKES G2 SANKEI SHO...P2 HEADLINE NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT call 732-747-8060. BY FAX AND INTERNET www.thoroughbreddailynews.com TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2002 KAZZIA ON FIRE N E W S Kazzia (Ger) (Zinaad {GB}) worked impressively at P P Newmarket yesterday morning ahead of Saturday’s GI Flower Bowl Invitational at WAR EMBLEM WORKS Belmont Park. Partnered by Ted War Emblem (Our Emblem) breezed five furlongs in Durcan, Godolphin’s G1 1000 1:01 3/5 Monday on the Santa Anita main track in Guineas and G1 Epsom Oaks preparation for his next, and final start, in the GI Breed- winner worked with stable ers’ Cup Classic set for Arlington Park Oct. 26. “We companion Naheef (Ire) (Marju went early with him, at 6:30 [a.m.],” said trainer Bob {Ire}) over seven furlongs of Baffert. “The way the weather has been [hot, dry], it is better to work early in the morning when there’s more the Round Gallop as she com- moisture in the track.” The winner of the GI Kentucky pleted her preparation. Racing Derby and GI Preakness S. was nominated to the GII Kazzia Manager Simon Crisford said of Goodwood Breeders’ Cup H. Oct. 6, but those plans Julian Herbert/Getty Images the filly, who left for the United were abandoned after the colt was sold for $17 million States yesterday evening, “The to Katsumi and Teruya Yoshida to stand stud in Japan filly worked really well this morning and we are in 2003. pleased with her.” NAYEF READY FOR AUTUMN TESTS INDIAN CHARLIE TO AIRDRIE Trainer Marcus Tregoning yesterday confirmed Nayef Indian Charlie (In Excess {Ire}--Soviet Sojourn, by (Gulch) on course for either the G1 Prix de l’Arc de Leo Castelli) has been moved to Mr. -

Flora-Lab-Manual.Pdf

LabLab MManualanual ttoo tthehe Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros Flora of New Mexico Lab Manual to the Flora of New Mexico Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros University of New Mexico Herbarium Museum of Southwestern Biology MSC03 2020 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM, USA 87131-0001 October 2009 Contents page Introduction VI Acknowledgments VI Seed Plant Phylogeny 1 Timeline for the Evolution of Seed Plants 2 Non-fl owering Seed Plants 3 Order Gnetales Ephedraceae 4 Order (ungrouped) The Conifers Cupressaceae 5 Pinaceae 8 Field Trips 13 Sandia Crest 14 Las Huertas Canyon 20 Sevilleta 24 West Mesa 30 Rio Grande Bosque 34 Flowering Seed Plants- The Monocots 40 Order Alistmatales Lemnaceae 41 Order Asparagales Iridaceae 42 Orchidaceae 43 Order Commelinales Commelinaceae 45 Order Liliales Liliaceae 46 Order Poales Cyperaceae 47 Juncaceae 49 Poaceae 50 Typhaceae 53 Flowering Seed Plants- The Eudicots 54 Order (ungrouped) Nymphaeaceae 55 Order Proteales Platanaceae 56 Order Ranunculales Berberidaceae 57 Papaveraceae 58 Ranunculaceae 59 III page Core Eudicots 61 Saxifragales Crassulaceae 62 Saxifragaceae 63 Rosids Order Zygophyllales Zygophyllaceae 64 Rosid I Order Cucurbitales Cucurbitaceae 65 Order Fabales Fabaceae 66 Order Fagales Betulaceae 69 Fagaceae 70 Juglandaceae 71 Order Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae 72 Linaceae 73 Salicaceae 74 Violaceae 75 Order Rosales Elaeagnaceae 76 Rosaceae 77 Ulmaceae 81 Rosid II Order Brassicales Brassicaceae 82 Capparaceae 84 Order Geraniales Geraniaceae 85 Order Malvales Malvaceae 86 Order Myrtales Onagraceae -

World Thoroughbred Racehorse Rankings Conference

EUROPEAN THOROUGHBRED RACEHORSE RANKINGS — 2010 TWO-YEAR-OLDS ICR Kg Age Sex Pedigree Owner Trainer Trained Name 126 57 Dream Ahead (USA) 2 C Diktat (GB)--Land of Dreams (GB) Mr Khalifa Dasmal David Simcock GB Frankel (GB) 2 C Galileo (IRE)--Kind (IRE) Mr K. Abdulla Henry Cecil GB 120 54.5 Pathfork (USA) 2 C Distorted Humor (USA)--Visions of Clarity (IRE) Silverton Hill Partnership Mrs J. Harrington IRE Wootton Bassett (GB) 2 C Iffraaj (GB)--Balladonia (GB) Frank Brady & The Cosmic Cases Richard Fahey GB 119 54 Casamento (IRE) 2 C Shamardal (USA)--Wedding Gift (FR) Sheikh Mohammed M. Halford IRE Roderic O'Connor (IRE) 2 C Galileo (IRE)--Secret Garden (IRE) Mrs Magnier, M. Tabor, D. Smith & A. P. O'Brien IRE Sangster Fam 117 53 Blu Constellation (ITY) 2 C Orpen (USA)--Stella Celtica (ITY) Scuderia Incolinx V. Caruso ITY Seville (GER) 2 C Galileo (IRE)--Silverskaya (USA) Mr M. Tabor, D. Smith & A. P. O'Brien IRE Mrs John Magnier 116 52.5 Hooray (GB) 2 F Invincible Spirit (IRE)--Hypnotize (GB) Cheveley Park Stud Sir Mark Prescott Bt GB 115 52 Maiguri (IRE) 2 C Panis (USA)--Zanada (FR) Ecurie Jarlan Christian Baillet FR Saamidd (GB) 2 C Street Cry (IRE)--Aryaamm (IRE) Godolphin Saeed bin Suroor GB Salto (IRE) 2 C Pivotal (GB)--Danzigaway (USA) Wertheimer et Frere F. Head FR Tin Horse (IRE) 2 C Sakhee (USA)--Joyeuse Entree (GB) Marquise de Moratalla D. Guillemin FR Zoffany (IRE) 2 C Dansili (GB)--Tyranny (GB) Mr M. Tabor, D. Smith & A. P. -

Vascular Plant Species of the Comanche National Grassland in United States Department Southeastern Colorado of Agriculture

Vascular Plant Species of the Comanche National Grassland in United States Department Southeastern Colorado of Agriculture Forest Service Donald L. Hazlett Rocky Mountain Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-130 June 2004 Hazlett, Donald L. 2004. Vascular plant species of the Comanche National Grassland in southeast- ern Colorado. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-130. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 36 p. Abstract This checklist has 785 species and 801 taxa (for taxa, the varieties and subspecies are included in the count) in 90 plant families. The most common plant families are the grasses (Poaceae) and the sunflower family (Asteraceae). Of this total, 513 taxa are definitely known to occur on the Comanche National Grassland. The remaining 288 taxa occur in nearby areas of southeastern Colorado and may be discovered on the Comanche National Grassland. The Author Dr. Donald L. Hazlett has worked as an ecologist, botanist, ethnobotanist, and teacher in Latin America and in Colorado. He has specialized in the flora of the eastern plains since 1985. His many years in Latin America prompted him to include Spanish common names in this report, names that are seldom reported in floristic pub- lications. He is also compiling plant folklore stories for Great Plains plants. Since Don is a native of Otero county, this project was of special interest. All Photos by the Author Cover: Purgatoire Canyon, Comanche National Grassland You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media.