Tax Policy and Economic Development in Maine: a Survey of the Issue Matthew .N Murray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES with a MARK to MARKET TAX on SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES WITH A MARK TO MARKET TAX ON SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D. Viard October 2016 ABSTRACT We propose reducing the corporate tax rate to 15 percent and replacing the foregone revenue with a tax at ordinary income rates on the accrued, or mark-to-market income of American shareholders of publicly traded corporations, accompanied by an imputation credit for U.S. corporate income taxes paid. The proposal would dramatically reduce the tax significance of the source of corporate profits and the residence of corporations, both of which can be easily manipulated. Lowering the corporate tax rate to 15 percent would encouraging a capital inflow to the United States and reduce incentives to shift reported profits overseas and engage in inversion transactions while continuing to impose tax on foreigners who earn economic rents from investing in the United States. The proposal includes provisions for averaging of mark-to- market income, transition relief for firms that move from closely held to publicly traded status, and other measures to address the challenges of mark-to-market taxation. We estimate that the proposal would be approximately revenue-neutral and would make the distribution of the tax burden slightly more progressive. A revised version of the article was been published in the September 2016 issue of the National Tax Journal, Volume 69 (3), 701-731. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Tax Policy Center or its funders. I. INTRODUCTION This paper presents a proposal for reform of the taxation of corporate income. -

2021 Revenue Ordinance

2021 Revenue Ordinance As Proposed on December 5, 2019 ii Revenue Ordinance of 2021 to Levy Taxes and Fees and Raise Revenue For the City of Savannah Georgia As adopted on December 18, 2020 Published by City of Savannah Revenue Department Post Office Box 1228 Savannah, GA 31402-1228 CITY OF SAVANNAH 2021 CITY COUNCIL Mayor Van R. Johnson, II Post 1 At-Large Post 2 At-Large Kesha Gibson-Carter Alicia Miller Blakely District 1 District 2 Bernetta B. Lanier Detric Leggett District 3 District 4 Linda Wilder-Bryan Nick Palumbo District 5 District 6 Dr. Estella Edwards Shabazz Kurtis Purtee Revenue Ordinance Compiled By Revenue Director/City Treasurer Ashley L. Simpson Utility Billing Manager Nicole Brantley Treasury Manager Joel Paulk Business Tax & Alcohol License Manager Judee Jones Revenue Special Projects Coordinator Saja Aures Table of Contents Revenue Ordinance of 2021 ....................................................................................................................... 1 ARTICLE A. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................... 1 Section 1. SCOPE; TAXES AND FEES .................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. DEFINITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 1 Section 3. JANUARY 1 GOVERNS FOR YEAR ...................................................................................... -

Improving the Tax System in Indonesia

OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 998 Improving the Tax System Jens Matthias Arnold in Indonesia https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k912j3r2qmr-en Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 30-Oct-2012 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 IMPROVING THE TAX SYSTEM IN INDONESIA ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 998 By Jens Arnold All OECD Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's Internet website at http://www.oecd.org/eco/Workingpapers English - Or. English JT03329829 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. ECO/WKP(2012)75 ABSTRACT/RESUME Improving the tax system in Indonesia Indonesia has come a long way in improving its tax system over the last decade, both in terms of revenues raised and administrative efficiency. Nonetheless, the tax take is still low, given the need for more spending on infrastructure and social protection. With the exception of the natural resources sector, increasing tax revenues would be best achieved through broadening tax bases and improving tax administration, rather than changes in the tax schedule that seems broadly in line with international practice. Possible measures to broaden the tax base include bringing more of the self-employed into the tax system, subjecting employer-provided fringe benefits and allowances to personal income taxation and reducing the exemptions from value-added taxes. -

Revenue Assignments in the Practice of Fiscal Decentralization

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University ECON Publications Department of Economics 2008 Revenue assignments in the practice of fiscal decentralization Jorge Martinez-Vazquez Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/econ_facpub Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Jorge Martinez-Vazquez. Revenue assignments in the practice of fiscal decentralization in Nuria Bosch and Jose M. Duran (eds.) Fiscal Federalism and Political Decentralization: Lessons from Spain, Germany and Canada, 27-55. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Economics at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ECON Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fiscal Federalism and Political Decentralization STUDIES IN FISCAL FEDERALISM AND STATE-LOCAL FINANCE Series Editor: Wallace E. Oates, Professor o f Economics, University o f Maryland, College Park and University Fellow, Resources for the Future, USA This important series is designed to make a significant contribution to the develop ment of the principles and practices of state-local finance. It includes both theo retical and empirical work. International in scope, it addresses issues of current and future concern in both East and West and in developed and developing countries. The main purpose of the series is to create a forum for the publication of high- quality work and to show how economic analysis can make a contribution to under standing the role of local finance in fiscal federalism in the twenty-first century. -

Panama Papers Leaks

GRAY TOLUB1 LLP Focusing on Domestic & International Taxation, Real Estate, Corporate, and Trust & Estate Matters. Client AlertAPRIL 04, 2016 AUTHORS Armin Gray Benjamin Tolub PANAMA PAPERS LEAKS: SUBJECT THE TAX MAN COMETH OVDP Panama On April 03, 2016, the press reported that 11.5 million records were leaked from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. The records detail offshore holdings of the celebrities, politicians, and the mega-rich many of which were purportedly engaged in illegal activities including tax evasion. Such leaks have been referred to as the “Panama papers” or the “Wikileaks of the mega-rich” by some newspapers.1 More details can be found at the website of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (“ICIJ”), which have summarized their findings as follows: The largest cross-border journalism collaboration ever has uncovered a giant leak of documents from Mossack Fonseca, a global law firm based in Panama. The secret files: • Include 11.5 million records, dating back nearly 40 years – making it the largest leak in offshore history. Contains details on more than 214,000 offshore entities connected to people in more than 200 countries and territories. Company owners 1 See Toppo, Greg, “Worldwide, jaws drop to Panama Papers’ Leak”, USA Today, last accessed April 3, 2016, available at: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/04/03/reactions- panama-papers-leak-go-global/82589874/. www.graytolub.com Client Alert Page 2 in [sic] billionaires, sports stars, drug smugglers and fraudsters. • Reveal the offshore holdings 140 politicians and public officials around the world – including 12 current and former world leaders. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California 1 Fred E. Foldvary, Colleen E. Haight, and Annette Nellen The authors conducted this study at the request of the California Senate Office of Research (SOR). This report presents the authors’ opinions and findings, which are not necessarily endorsed by the SOR. 1 Dr. Fred E. Foldvary, Lecturer, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their funding. Executive Summary This study attempts to answer the question: should California broaden its use of a consumption tax, and if so, how? In considering this question, we must also consider the ultimate purpose of a system of taxation: namely to raise sufficient revenues to support the spending goals of the state in the most efficient manner. Recent tax reform proposals in California have included a business net receipts tax (BNRT), as well as a more comprehensive sales tax. However, though the timing is right, given the increasingly global and digital nature of California’s economy, the recent 2008 recession tabled the discussion in favor of more urgent matters. -

The Offshore Tax Enforcement Dragnet

Emory Law Journal Volume 67 Issue 4 2018 The Offshore Tax Enforcement Dragnet Shu-Yi Oei Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Shu-Yi Oei, The Offshore Tax Enforcement Dragnet, 67 Emory L. J. 655 (2018). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol67/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OEI GALLEYPROOFS 4/23/2018 12:07 PM THE OFFSHORE TAX ENFORCEMENT DRAGNET Shu-Yi Oei* ABSTRACT Taxpayers who hide assets abroad to evade taxes present a serious enforcement challenge for the United States. In response, the United States has developed a family of initiatives that punish and rehabilitate non-compliant taxpayers, raise revenues, and require widespread reporting of offshore financial information by financial institutions and taxpayers. Yet, while these initiatives help catch willful tax cheats, they have also adversely affected immigrants, Americans living abroad, and “accidental Americans.” This Article critiques the United States’ offshore tax enforcement initiatives, such as the Foreign Account Tax Compliant Act and the Internal Revenue Service’s offshore voluntary disclosure programs. It argues that the United States has been overly focused on two policy priorities in designing enforcement at the expense of competing considerations: First, the United States has attempted to equalize enforcement against taxpayers with solely domestic holdings and those with harder-to-detect offshore holdings by imposing harsher reporting requirements and penalties on the latter. -

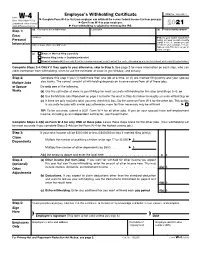

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting By Mark Holtzblatt, Eva K. Jermakowicz and Barry J. Epstein MARK HOLTZBLATT, Ph.D., CPA, is an Associate Professor of Accounting at Cleveland State University in the Monte Ahuja College of Business, teaching In- ternational Accounting and Taxation at the graduate and undergraduate levels. axes paid to governments are among the most significant costs incurred by businesses and individuals. Tax planning evaluates various tax strategies in Torder to determine how to conduct business (and personal transactions) in ways that will reduce or eliminate taxes paid to various governments, with the objective, in the case of multinational corporations, of minimizing the aggregate of taxes paid worldwide. Well-managed entities appropriately attempt to minimize the taxes they pay while making sure they are in full compliance with applicable tax laws. This process—the legitimate lessening of income tax expense—is often EVA K. JERMAKOWICZ, Ph.D., CPA, is a referred to as tax avoidance, thus distinguishing it from tax evasion, which is illegal. Professor of Accounting and Chair of the Although to some listeners’ ears the term tax avoidance may sound pejorative, Accounting Department at Tennessee the practice is fully consistent with the valid, even paramount, goal of financial State University. management, which is to maximize returns to businesses’ ownership interests. Indeed, to do otherwise would represent nonfeasance in office by corporate managers and board members. Multinational corporations make several important decisions in which taxation is a very important factor, such as where to locate a foreign operation, what legal form the operations should assume and how the operations are to be financed. -

2021 Legislative Synopsis

Legislative Synopsis 2021 Indiana Department of Revenue INTRODUCTION The Legislative Synopsis contains a list of legislation passed by the 2021 Indiana General Assembly affecting the Indiana Department of Revenue (DOR). DOR’s synopsis has been divided into two parts with each presenting the same information, but organized differently. The first part is organized according to tax type and the second by bill number. For each legislative change, the synopsis includes the heading (the relevant tax type in the first part; the enrolled act number in the second part), short summary, effective date, affected Indiana Code cites and section of the bill where the language appears. FINDING INDIANA CODE AND LEGISLATION ONLINE To find laws contained in Indiana Code, get more information about all the recently passed legislation or to read the bills in their entirety, go to the Indiana General Assembly’s website at iga.in.gov. Indiana Code is arranged by Title, Article, Chapter and Section. To find information contained in Indiana Code, on the Indiana General Assembly’s website, do the following: 1. At the top of the web page, click “Laws” and then click “Indiana Code.” Every Title of the Indiana Code appears on this page. 2. Click the Title you want to review. 3. Next, choose the Article you want to review. All the Chapters in the Article are listed on the left side of the page. 4. Click the Chapter you want to review. All Sections of the Chapter will appear, including the Section of the Indiana Code you want to examine. To see the bill containing the specific language, do the following: 1.