Kakuban's Incorporation of Pure Land Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

Phowa Teaching 2014

Amitabha Foundation Australia His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche: Sydney Teachings 2014 Phowa, Achi Chokyi Drolma and 10-Levels Buddha Amitabha PHOWA: Going Directly to the Pure Land of Buddha Amitabha at Death What is Phowa? None of us can escape death. Many of us fear it. But death gives us the most precious opportunity: to transfer our minds directly to the blissful Pure Land of Buddha Amitabha. We can do this through the Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayana practice known as Phowa. Phowa is the simplest and most direct way to attain enlightenment without a lifetime of disciplined spiritual practice, so it is very suited to the people of today who want clear results and a fast path. In Phowa training, the compassion of Buddha Amitabha, the power of a great Phowa Master’s transmission blessing, and the devotion of the student combine to produce clear signs of accomplishment. e student can then face death whenever it comes with joyful condence. About His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche has been recognized by many great Buddhist Masters, including HH Dalai Lama, HH 16th Gyalwang Karmapa, and HH Dudjom Rinpoche to be the greatest Phowa Master living in the world today. He is the incarnation of Terton Choegyal Dorje, a Drikung Kagyu Lama previously born as the Bodhisattva Ruchiraketu (a disciple of Shakyamuni Buddha and recorder of the famous Golden Light Sutra), Langdro Lotsawa (one of the great disciples of Guru Rinpoche) and Repa Shiwa Ö (a close disciple of Milarepa). At the specic request of HH Dalai Lama and HH Karmapa, Rinpoche has been teaching Phowa internationally since 1963. -

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno Instructor: Mark T. Unno, Office: SCH 334 TEL 6-4973, munno (at) uoregon.edu http://pages.uoregon.edu/munno/ Wed. 2:00 p.m. - 4:50 p.m., Condon 330; Office Hours: Mon 10:00-10:45 a.m.; Tues 1:00-1:45 p.m. No Canvas site. Overview REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism focuses on selected strains of Japanese Buddhism during the medieval period, especially the Kamakura (1185-1333), but also traces influences on later developments including the modern period. The course weaves together the examination of religious thought and cultural developments in historical context. We begin with an overview of key Buddhist concepts for those without prior exposure and go onto examine the formative matrix of early Japanese religion. Once some of the outlines of the intellectual and cultural framework of medieval Japanese Buddhism have been brought into relief, we will proceed to examine in depth examples of significant medieval developments. In particular, we will delve into the work of three contemporary figures: Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253), Zen master and founding figure of the Sōtō sect; Myōe of the Shingon and Kegon sects, focusing on his Shingon practices; and Shinran, founding figure of Jōdo Shinshū, the largest Pure Land sect, more simply known as Shin Buddhism. We conclude with the study of some modern examples that nonetheless are grounded in classical and medieval sources, thus revealing the ongoing influence and transformations of medieval Japanese Buddhism. Themes of the course include: Buddhism as state religion; the relation between institutional practices and individual religious cultivation; ritual practices and transgression; gender roles and relations; relations between ordained and lay; religious authority and enlightenment; and two-fold truth and religious practice. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Religion and Culture

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/2: 355–375 © 2013 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture review article Constructing Histories, Thinking Ritual Gatherings, and Rereading “Native” Religion A Review of Recent Books Published in Japanese on Premodern Japanese Religion (Part Two) Brian O. Ruppert Histories of Premodern Japanese Religion We can start with Yoshida Kazuhiko’s 吉田一彦 Kodai Bukkyō o yominaosu 古代仏 教 をよみ なお す (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2006), since it seems in many ways like a founder and precursor of the range of works written recently concerning early and, to some extent, medieval Japanese religion. Yoshida, who has long attempted to overcome common misconceptions concerning early Buddhism, succinctly tries to correct the public’s “common sense” (jōshiki 常識). Highlights include clarifications, including reference to primary and secondary sources that “Shōtoku Taishi” is a historical construction rather than a person, and even the story of the destruction of Buddhist images is based primarily on continental Buddhist sources; “popular Buddhism” does not begin in the Kamakura period, since even the new Kamakura Buddhisms as a group did not become promi- nent until the late fifteenth century; discourses on kami-Buddha relations in Japan were originally based on Chinese sources; for early Japanese Buddhists (including Saichō, Kūkai, and so on), Japan was a Buddhist country modeling Brian O. Ruppert is an associate professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cul- tures, University of Illinois. 355 356 | Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/2 (2013) its Buddhism on the continent; and the term for the sovereign tennō, written as “heavenly thearch” 天皇, was based on Chinese religious sources and only used from the late seventh century. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

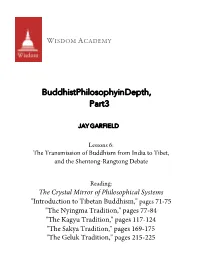

Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3

WISDOM ACADEMY Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3 JAY GARFIELD Lessons 6: The Transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet, and the Shentong-Rangtong Debate Reading: The Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems "Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism," pages 71-75 "The Nyingma Tradition," pages 77-84 "The Kagyu Tradition," pages 117-124 "The Sakya Tradition," pages 169-175 "The Geluk Tradition," pages 215-225 CrystalMirror_Cover 2 4/7/17 10:28 AM Page 1 buddhism / tibetan THE LIBRARY OF $59.95US TIBETAN CLASSICS t h e l i b r a r y o f t i b e t a n c l a s s i c s T C! N (1737–1802) was L T C is a among the most cosmopolitan and prolific Tspecial series being developed by e Insti- Tibetan Buddhist masters of the late eighteenth C M P S, by Thuken Losang the crystal tute of Tibetan Classics to make key classical century. Hailing from the “melting pot” Tibetan Chökyi Nyima (1737–1802), is arguably the widest-ranging account of religious Tibetan texts part of the global literary and intel- T mirror of region of Amdo, he was Mongol by heritage and philosophies ever written in pre-modern Tibet. Like most texts on philosophical systems, lectual heritage. Eventually comprising thirty-two educated in Geluk monasteries. roughout his this work covers the major schools of India, both non-Buddhist and Buddhist, but then philosophical large volumes, the collection will contain over two life, he traveled widely in east and inner Asia, goes on to discuss in detail the entire range of Tibetan traditions as well, with separate hundred distinct texts by more than a hundred of spending significant time in Central Tibet, chapters on the Nyingma, Kadam, Kagyü, Shijé, Sakya, Jonang, Geluk, and Bön schools. -

Pure Land Buddhism and Christianity

NANZAN SYMPOSIUM VII SALVATION AND ENLIGHTENMENT: PURE LAND BUDDHISM AND CHRISTIANITY [4-6 September 1989] JAN VAN BRAGT It may seem a bit strange or unnatural that this dialogue session with representatives of the Pure Land School occurred so late in the day, namely only as number seven in the ongoing bi-annual series of Nanzan Symposia. This in view of the fact that the Pure Land denom inational communities, certainly when taken together, constitute the strongest “branch” of Buddhism in Japan and,moreover, Pure Land thinking and devotion deeply influenced Japanese religiosity in gen eral. And also because, on the face of it, Pure Land Buddhism and Christianity, sharing as they do the idea of salvation by “Other-Power,” show such a close affinity in their religiosity. To this we can only plead guilty: post factum the lateness of this “j6do Symposium” looks uncalled-for even to us,members of the Institute. On the other hand, however, we can honestly say that in the daily activities of the Institute —as opposed to such highlights as symposia — dialogue with Shinshu people has loomed large (larger than the dialogue with any other of Japan’s religious communities) right from the beginning (now 15 years ago), both through meetings held at the Institute itself and through participation by members of the Institute in sessions held at Shinshu headquarters or universities. It is thus no mere subterfuge to say that this symposium happened so late mainly because of circumstances “beyond our will.” With regard to the alleged affinity between Christianity and Pure Land Buddhism, it may be relevant to remark here that most Pure Land scholars in Japan, or at least most Shinshu scholars, rather tend to stress the great difference between Christian thinking and Pure Land thinking. -

In One Lifetime: Pure Land Buddhism

In One Lifetime: Pure Land Buddhism % In One Lifetime: Pure Land Buddhism Shi Wuling Amitabha Publications Chicago Venerable Wuling is an American Buddhist nun of the Pure Land school of Mahayana Buddhism. Amitabha Publications, Chicago © 2006 by Amitabha Publications Some rights reserved. No part of this book may not be altered without permission from the publisher. Reprinting is allowed for non-profit use. For the latest edition, contact [email protected] “The Ten-Recitation Method” is a translation based on a talk by Venerable Master Chin Kung Chapters 1, 3, and 4 contain excerpts from Awaken to the Buddha Within by Venerable Wuling 10 09 08 07 06 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN: 978-1-59975-357-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2006927171 Printed by: The Pure Land Learning College Association, Inc. 57 West St., Toowoomba, QLD 4350, Australia Tel: 61-7-4637-8765 Fax: 61-7-4637-8764 www.amtb-aus.org For more teachings and gifts of the Dharma, please visit us at www.amitabha-publications.org Contents Pure Land Buddhism 1 Chanting 6 Cultivation 8 The Five Guidelines 27 Dharma Materials 41 Visiting a Buddhist Center 42 Chanting Session 44 Thoughts from Master Yin Guang 48 Closing Thoughts 50 Ways to Reach Us 52 Pure Land Buddhism Once, the Buddha was asked if he was a god. The Buddha replied that no, he was not a god. Then was he an angel? No. A spirit? No. Then what was he? The Buddha replied that he was awakened. Since the Buddha, by his own assertion, is not a god, we do not worship him. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Spring 2021 Volume 48(PDF)

Religions for Peace Japan First World Assembly in Kyoto, Sixth World Assembly in Rome Japan, 1970 and Riva del Garda, Italy, 1994 Religions for Peace was established in 1970 as an international nongovernmental organization. It obtained general consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 1999. As an international network of religious communities encompassing over ninety countries, the Religions for Peace family engages in conflict resolution, humanitarian assistance, and other peace-building activities through dialogue and coop- eration across religions. Second World Assembly in Religions for Peace Japan was established in 1972 as a commit- Seventh World Assembly in Leuven, Belgium, 1974 tee for the international issues supported by Japanese Association Amman, Jordan, 1999 of Religious Organizations. Since then it has served as the national chapter of Religions for Peace. 1. Calling on religious communities to deeply reflect on their practices, address any that are exclusionary in nature, and engage in dialogue with one another in the spirit of toler- ance and understanding. Third World Assembly in 2. Facilitating multireligious collaboration in making peace Eighth World Assembly in Princeton, the United States, 1979 initiatives. Kyoto, Japan, 2006 3.Working with peace organizations in all sectors and coun- tries to address global issues. 4. Implementing religiously based peace education and aware- ness-raising activities. ! Religions for Peace Japan promotes activities under the slogan: “Caring for Our Common Future: Advancing Shared Well-Being,” which include cooperating and collaborating with Religions for Fourth World Assembly in Ninth World Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya, 1984 Peace and Religions for Peace Asia; participating in the Non- Vienna, Austria, 2013 Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference; cooperating and collaborating with both international and local faith-based organ- izations; and building networks with various sectors (politics, economics, academics, culture, media, and so forth). -

Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/3-4 Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship Jacqueline I. Stone This article places Nichiren within the context of three larger scholarly issues: definitions of the new Buddhist movements of the Kamakura period; the reception of the Tendai discourse of original enlightenment (hongaku) among the new Buddhist movements; and new attempts, emerging in the medieval period, to locate “Japan ” in the cosmos and in history. It shows how Nicmren has been represented as either politically conservative or rad ical, marginal to the new Buddhism or its paradigmatic figv/re, depending' upon which model of “Kamakura new Buddhism” is employed. It also shows how the question of Nichiren,s appropriation of original enlighten ment thought has been influenced by models of Kamakura Buddnism emphasizing the polarity between “old” and “new,institutions and sug gests a different approach. Lastly, it surveys some aspects of Nichiren ys thinking- about “Japan ” for the light they shed on larger, emergent medieval discourses of Japan relioiocosmic significance, an issue that cuts across the “old Buddhism,,/ “new Buddhism ” divide. Keywords: Nichiren — Tendai — original enlightenment — Kamakura Buddhism — medieval Japan — shinkoku For this issue I was asked to write an overview of recent scholarship on Nichiren. A comprehensive overview would exceed the scope of one article. To provide some focus and also adumbrate the signifi cance of Nichiren studies to the broader field oi Japanese religions, I have chosen to consider Nichiren in the contexts of three larger areas of modern scholarly inquiry: “Kamakura new Buddhism,” its relation to Tendai original enlightenment thought, and new relisdocosmoloei- cal concepts of “Japan” that emerged in the medieval period.