Metal Burial: Understanding Caching Behaviour And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Common Name Scientific Name Description of Plant Picture of Plant

Plant common name Description of Plant Picture of Plant Scientific name Strangler Fig The Strangler Fig begins life as a small vine-like plant Ficus thonningii that climbs the nearest large tree and then thickens, produces a branching set of buttressing aerial roots, and strangles its host tree. An easy way to tell the difference between Strangle Figs and other common figs is that the bottom half of the Strangler is gnarled and twisted where it used to be attached to its host, the upper half smooth. A common tree on kopjes and along rivers in Serengeti; two massive Fig trees near Serengeti; the "Tree Where Man was Born" in southern Loliondo, and the "Ancestor Tree" near Endulin, in Ngorongoro are significant for the local Maasai peoples. Wild Date Palm Palms are monocotyledons, the veins in their leaves Phoenix reclinata are parallel and unbranched, and are thus relatives of grasses, lilies, bananas and orchids. The wild Date Palm is the most common of the native palm trees, occurring along rivers and in swamps. The fruits are edible, though horrible tasting, while the thick, sugary sap is made into Palm wine. The tree offers a pleasant, softly rustling, fragrant-smelling shade; the sort of shade you will need to rest in if you try the wine. Candelabra The Candelabra tree is a common tree in the western Euphorbia and Northern parts of Serengeti. Like all Euphorbias, Euphorbia the Candelabra breaks easily and is full of white, candelabrum extremely toxic latex. One drop of this latex can blind or burn the skin. -

A Consideration of 'Nomina Subnuda'

51 February 2002: 171–174 Brummitt Nomina subnuda NOMENCLATURE Edited by John McNeill Aconsideration of “nomina subnuda” R. K. Brummitt The Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, U.K. E-mail: r.brummitt@ rbkew.org.uk. Many names were originally published with very kind as those seen at Vansittart Bay last year; the arbores- short or non-technical descriptions, and it is often un- cent gouty species of this genus ( Capparis gibbosa , A. clear whether these meet the requirements of Art. 32.1 Cunn.) which was first observed on the shores of (c) for valid publication. Such names are often referred to Cambridge Gulf, is frequent here, growing to an enor- as “nomina subnuda”. The Committee for Spermato- mous size, and laden with large fruit”. Of the present phyta, in considering proposals to conserve or reject, has Committee, five said that they would treat the name as often had to decide whether to accept such names as valid, while eight said they would not (two not voting). validly published or not. Current examples include The name later turned out to be an earlier synonym of Proposal 1400 to reject Capparis gibbosa A. Cunn. (see Adansonia gregorii F. Muell. (in a different family from below). Furthermore, although there is no provision in Capparis), and a proposal to reject C. gibbosa A. Cunn. the Code for committee recommendations in such cases (Prop. 1400) was published by Paul G. Wilson & G. P. (as there is under Art. 53.5, in deciding whether two sim- Guymer in Taxon 48: 175–176 (1999). -

Baobab (Not Boabab) Species General Background Germinating

Baobab (not Boabab) Species Baobab is the common name of a genus (Adansonia) with eightspecies of trees, 6 species in Madagascar; 1 in Africa and 1 in Australia. Adansonia gregorii (A.gibbosa) or Australian Baobab (northwest Australia) Adansonia madaf Zascariensis or Madagascar Baobab (Madagascar) Adansonia perrieri or Perrier's Baobab (North Madagascar) Adansonia rubrostipa or Fony Baobab (Madagascar) Adansonia suarezensis or Suarez Baobab Diego Suarez,(Madagascar) Adansonia za or Za Baobab (Madagascar) The name Adansonia honours Michel Adanson, the French naturalist and explorer who described A. digitata. General Background One of the earliest written references to the Baobab tree was made by the Arabic traveller, Al-Bakari in 1068. In 1592, the Venetian herbalist and physician, Prospero Alpino, reported a fruit in the markets of Cairo as "BU HUBAB". It is believed that the name is derived from the Arabic word Bu Hibab which means fruit with many seeds. Common names include bottle tree and monkey bread tree. Baobab - derived from African fokelore "upside-down-tree". The story is after the creation each of the animals were given a tree to plant and the stupid hyena planted the baobab upside-down. The baobab is the national tree of Madagascar. Height is 5-25m tall and trunk diameter of up to 7m. The Baobab can store up to 120 000 lt of water inside the swollen trunk to endure harsh drought conditions. All occur in seasonal arid areas and are deciduous, losing leaves during dry season. It is believed that the elephant must digest the seed before it will germinate as the heat and stomach acids help to soften the shell. -

Adansonia Gregorii; Bombaceae

A.E. Orchard, Allan Cunningham and the Boab (Bombaceae) 1 Nuytsia The journal of the Western Australian Herbarium 28: 1–9 Published online 20 January 2017 Allan Cunningham and the Boab (Adansonia gregorii; Bombaceae) Anthony E. Orchard c/o Australian Biological Resources Study, GPO Box 787, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Email: [email protected] Abstract Orchard, A.E. Allan Cunningham and the Boab (Adansonia gregorii; Bombaceae). Nuytsia 28: 1–9 (2017). The Australian Boab, now known as Adansonia gregorii F.Muell. was first noticed botanically by Allan Cunningham during Phillip Parker King’s second survey voyage in 1819, and first collected by Cunningham in the following year at Careening Bay. Cunningham saw only fruiting material, and considered the tree to belong to the genus Capparis L., giving it the manuscript name C. gibbosa A.Cunn. He described but did not formally name the species in King’s Narrative of a Survey. The name was published with a valid description in Heward’s biography of Cunningham in 1842. In the interim Cunningham had drafted a paper comparing his species with the African genus Adansonia Juss., but unfortunately never published it. Subsequently Mueller described the species again, as A. gregorii F.Muell., based on specimens collected near the Victoria and Fitzmaurice Rivers, and this name became accepted for the species. In 1995 Baum recognised that the two descriptions referred to the same taxon, and made the combination Adansonia gibbosa (A.Cunn.) Guymer ex D.Baum. A subsequent referral to the Spermatophyta Committee and General Committee resulted in the name C. -

Anniversary Adventure April 2015

n 9 Pear-fruited Mallee, Eucalyptus pyriformis. A Tour of Trees. 10 Mottlecah, Eucalyptus macrocarpa. Dive into the Western Australian Botanic Garden on an Anniversary Adventure and 11 Rose Mallee, discover its best kept secrets. Eucalyptus rhodantha. 1 Silver Princess, 12 Marri, Explore a special area of the Western Eucalyptus caesia. Australian Botanic Garden with us each Corymbia calophylla. month as we celebrate its 50th anniversary 2 Kingsmill’s Mallee, 13 Western Australian Christmas Tree, in 2015. Eucalyptus kingsmillii. Nuytsia floribunda. In April, we take a winding tour through the 3 Large-fruited Mallee, 14 Dwellingup Mallee, botanic garden to see the most distinctive, Eucalyptus youngiana. Eucalyptus drummondii x rudis rare and special trees scattered throughout its 4 Boab – Gija Jumulu*, (formerly Eucalyptus graniticola). 17 hectares. Adansonia gregorii. 15 Scar Tree – Tuart, 5 Variegated Peppermint, Eucalyptus gomphocephala. Agonis flexuosa. 16 Ramel’s Mallee, 6 Tuart, Eucalyptus rameliana. Eucalyptus gomphocephala. 17 Salmon White Gum, 7 Karri, Eucalyptus lane-poolei. Eucalyptus diversicolor. 18 Red-capped Gum or Illyarrie, 8 Queensland Bottle Tree, Eucalyptus erythrocorys. Brachychiton rupestris. * This Boab, now a permanent resident in Kings Park, was a gift to Western Australia from the Gija people of the East Kimberley. Jumulu is the Gija term for Boab. A Tour of Trees. This month, we take a winding tour through Descend the Acacia Steps to reach the Water Garden the Western Australian Botanic Garden to see where you will find a grove of Dwellingup Mallee the most distinctive, rare and special trees (Eucalyptus drummondii x rudis – formerly Eucalyptus granticola). After discovering a single tree in the wild, scattered throughout its 17 hectares. -

Adansonia Gregorii Tree Information

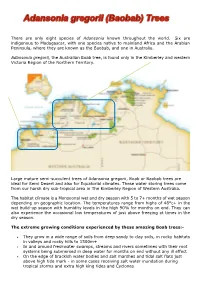

There are only eight species of Adansonia known throughout the world. Six are indigenous to Madagascar, with one species native to mainland Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, where they are known as the Baobab, and one in Australia. Adansonia gregorii, the Australian Boab tree, is found only in the Kimberley and western Victoria Region of the Northern Territory. Large mature semi-succulent trees of Adansonia gregorii, Boab or Baobab trees are ideal for Semi Desert and also for Equatorial climates. These water storing trees come from our harsh dry sub-tropical area in The Kimberley Region of Western Australia. The habitat climate is a Monsoonal wet and dry season with 5 to 7+ months of wet season depending on geographic location. The temperatures range from highs of 48°c+ in the wet build-up season with humidity levels in the high 90% for months on end. They can also experience the occasional low temperatures of just above freezing at times in the dry season. The extreme growing conditions experienced by these amazing Boab trees:- • They grow in a wide range of soils from deep sandy to clay soils, in rocky habitats in valleys and rocky hills to 1500m+ • In and around freshwater swamps, streams and rivers sometimes with their root systems being submersed in deep water for months on end without any ill effect • On the edge of brackish water bodies and salt marshes and tidal salt flats just above high tide mark - in some cases receiving salt water inundation during tropical storms and extra high king tides and Cyclones • They also grow in soils with salt contents higher that most plants can withstand The waxy feeling skin/bark of the Boab will also adapt to extremely hot sunlight conditions in the dry season when it may shed all of its leaves (depending on whether the tree is growing in dry or moist situation). -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

Bardi Plants an Annotated List of Plants and Their Use

H.,c H'cst. /lust JIus lH8f), 12 (:J): :317-:359 BanE Plants: An Annotated List of Plants and Their Use by the Bardi Aborigines of Dampierland, in North-western Australia \!o\a Smith and .\rpad C. Kalotast Abstract This paper presents a descriptive list of the plants identified and used by the BarcE .\borigines of the Dampierland Peninsula, north~\q:stern Australia. It is not exhaust~ ive. The information is presented in two wavs. First is an alphabetical list of Bardi names including genera and species, use, collection number and references. Second is a list arranged alphabetically according to botanical genera and species, and including family and Bardi name. Previous ethnographic research in the region, vegetation communities and aspects of seasonality (I) and taxonomy arc des~ cribed in the Introduction. Introduction At the time of European colonisation of the south~west Kimberley in the mid nineteenth century, the Bardi Aborigines occupied the northern tip of the Dam pierland Peninsula. To their east lived the island-dwelling Djawi and to the south, the ~yulnyul. Traditionally, Bardi land ownership was based on identification with a particular named huru, translated as home, earth, ground or country. Forty-six bum have been identified (Robinson 1979: 189), and individually they were owned by members of a family tracing their ownership patrilineally, and known by the bum name. Collectively, the buru fall into four regions with names which are roughly equivalent to directions: South: Olonggong; North-west: Culargon; ~orth: Adiol and East: Baniol (Figure 1). These four directional terms bear a superficial resemblance to mainland subsection kinship patterns, in that people sometimes refer to themselves according to the direction in which their land lies, and indeed 'there are. -

Commercialisation of Boab Tubers

Commercialisation of Boab Tubers A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation By P.R. Johnson, E.J. Green, M. Crowhurst, C.J. Robinson September 2006 RIRDC Publication No 06/022 RIRDC Project No DAW-108A © 2006 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 285 9 ISSN 1440-6845 Commercialisation of Boab Tubers Publication No. 06/022 Project No DAW-108A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable industries. The information should not be relied upon for the purpose of a particular matter. Specialist and/or appropriate legal advice should be obtained before any action or decision is taken on the basis of any material in this document. The Commonwealth of Australia, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, the authors or contributors do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person's use or reliance upon the content of this document. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Peter Johnson Department of Agriculture Western Australia PO Box 19 Kununurra Phone: (08) 9166 4000 Fax: (08) 9166 4066 Email: [email protected] In submitting this report, the researcher has agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 2, Pharmacy Guild House 15 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4819 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected]. -

Genetic Diversity and Biogeography of the Boab Adansonia Gregorii (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae)

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Botany, 2014, 62, 164–174 http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/BT13209 Genetic diversity and biogeography of the boab Adansonia gregorii (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae) Karen L. Bell A,B,E, Haripriya Rangan B, Rachael Fowler A,B, Christian A. Kull B, J. D. Pettigrew C, Claudia E. Vickers D and Daniel J. Murphy A ARoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. BSchool of Geography and Environmental Science, Monash University, Clayton, Vic. 3800, Australia. CQueensland Brain Institute, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Qld 4072, Australia. DAustralian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Qld 4072, Australia. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Kimberley region of Western Australia is recognised for its high biodiversity and many endemic species, including the charismatic boab tree, Adansonia gregorii F.Muell. (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae). In order to assess the effects of biogeographic barriers on A. gregorii, we examined the genetic diversity and population structure of the tree species across its range in the Kimberley and adjacent areas to the east. Genetic variation at six microsatellite loci in 220 individuals from the entire species range was examined. Five weakly divergent populations, separated by west–east and coast–inland divides, were distinguished using spatial principal components analysis. However, the predominant pattern was low geographic structure and high gene flow. Coalescent analysis detected a population bottleneck and significant gene flow across these inferred biogeographic divides. Climate cycles and coastline changes following the last glacial maximum are implicated in decreases in ancient A. gregorii population size. Of all the potential gene flow vectors, various macropod species and humans are the most likely. -

Critical Revision of the Genus Eucalyptus Volume 7: Parts 61-70

Critical revision of the genus eucalyptus Volume 7: Parts 61-70 Maiden, J. H. (Joseph Henry) (1859-1925) University of Sydney Library Sydney 2002 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/oztexts © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition of Parts 61-70 Critical revision of the genus eucalyptus, published by William Applegate Gullick Sydney 1929. 494pp. All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1929 583.42 Australian Etext Collections at botany prose nonfiction 1910-1939 Critical revision of the genus eucalyptus volume 7 (Government Botanist of New South Wales and Director of the Botanic Gardens, Sydney) “Ages are spent in collecting materials, ages more in separating and combining them. Even when a system has been formed, there is still something to add, to alter, or to reject. Every generation enjoys the use of a vast hoard bequeathed to it by antiquity, and transmits that hoard, augmented by fresh acquisitions, to future ages. In these pursuits, therefore, the first speculators lie under great disadvantages, and, even when they fail, are entitled to praise.” Macaulay's “Essay on Milton” Sydney William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer 1929 Part 61 CCCLII. E. fastigata Deane and Maiden. In Proc. Linn. Soc. N.S.W., xxx, 809, with Plate lxi (1896). See also Part VII, p. 185, of the present work, where the description is printed, and where the species is looked upon as a form of E. regnans F.v.M., but not described as a variety. -

(Adansonia Gregorii). 2 3 4 5 JD Pettigrew FRS1 6 7 8 9 Queensland Brain Institute1 10 11 Emeritus Prof

1 Controversial Timing for the Arrival in Australia of the Boab (Adansonia gregorii). 2 3 4 5 JD Pettigrew FRS1 6 7 8 9 Queensland Brain Institute1 10 11 Emeritus Prof. JD Pettigrew 12 [email protected] 13 14 15 16 6842 words 17 18 Abstract: The Australian baobab, or Boab, (Adansonia gregorii), is mysteriously separated 19 from the remaining 8 African and Madagascan species in its genus by the Indian Ocean. 20 Information about the time of the Boab’s arrival in Australia was sought using the 21 molecular genetics of the nITS gene in 220 Boabs sampled from their complete distribution 22 across the Kimberley. nITS substitutions had limited diversity (0.36%), in keeping with the 23 “young” genetics shown by DNA microsatellites in another study. There were more 24 substitutions in NW trees compared with those at the Eastern limit of its distribution 25 around the Victoria River, which are presumed to be more recent. Coalescence time and 26 divergence time could be based on reliable data concerning the range of nITS substitutions 27 in the Boab and their divergence from the African baobab sister species, but these 28 estimations had a stumbling block:- there is no reliable estimate of the mutation rate for 29 the nITS gene of the Boab. Earlier publications made the assumption that the mutation 30 rate for the Boab was the same as that of its African sister taxon (Adansonia digitata). This 31 risky assumption gives a divergence time of 2.4 Ma that is discrepant with other studies, 32 such as microsatellites, that indicate a much younger age.