La Bienal 2013: Here Is Where We Jump!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Family's Guide to Explore NYC for FREE with Your Cool Culture Pass

coolculture.org FAMILY2019-2020 GUIDE Your family’s guide to explore NYC for FREE with your Cool Culture Pass. Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org WELCOME TO COOL CULTURE! Whether you are a returning family or brand new to Cool Culture, we welcome you to a new year of family fun, cultural exploration and creativity. As the Executive Director of Cool Culture, I am excited to have your family become a part of ours. Founded in 1999, Cool Culture is a non-profit organization with a mission to amplify the voices of families and strengthen the power of historically marginalized communities through engagement with art and culture, both within cultural institutions and beyond. To that end, we have partnered with your child’s school to give your family FREE admission to almost 90 New York City museums, historic societies, gardens and zoos. As your child’s first teacher and advocate, we hope you find this guide useful in adding to the joy, community, and culture that are part of your family traditions! Candice Anderson Executive Director Cool Culture 2020 Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org HOW TO USE YOUR COOL CULTURE FAMILY PASS You + 4 = FREE Extras Are Extra Up to 5 people, including you, will be The Family Pass covers general admission. granted free admission with a Cool Culture You may need to pay extra fees for special Family Pass to approximately 90 museums, exhibits and activities. Please call the $ $ zoos and historic sites. museum if you’re unsure. $ More than 5 people total? Be prepared to It’s For Families pay additional admission fees. -

El Museo Del Barrio 50Th Anniversary Gala Honoring Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Raphael Montañez Ortíz, and Craig Robins

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EL MUSEO DEL BARRIO 50TH ANNIVERSARY GALA HONORING ELLA FONTANALS-CISNEROS, RAPHAEL MONTAÑEZ ORTÍZ, AND CRAIG ROBINS For images, click here and here New York, NY, May 5, 2019 - New York Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed from the stage of the Plaza Hotel 'Dia de El Museo del Barrio' at El Museo's 50th anniversary celebration, May 2, 2019. "The creation of El Museo is one of the moments where history started to change," said the Mayor as he presented an official proclamation from the City. This was only one of the surprises in a Gala evening that honored Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Craig Robins, and El Museo's founding director, artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz and raised in excess of $1.2 million. El Museo board chair Maria Eugenia Maury opened the evening with spirited remarks invoking Latina activist Dolores Huerta who said, "Walk the streets with us into history. Get off the sidewalk." The evening was MC'd by WNBC Correspondent Lynda Baquero with nearly 500 guests dancing in black tie. Executive director Patrick Charpenel expressed the feelings of many when he shared, "El Museo del Barrio is a museum created by and for the community in response to the cultural marginalization faced by Puerto Ricans in New York...Today, issues of representation and social justice remain central to Latinos in this country." 1230 Fifth Avenue 212.831.7272 New York, NY 10029 www.elmuseo.org Artist Rirkrit Travanija introduced longtime supporter Craig Robins who received the Outstanding Patron of Art and Design Award. Craig graciously shared, "The growth and impact of this museum is nothing short of extraordinary." El Museo chairman emeritus and artist, Tony Bechara, introduced Ella Fontanals-Cisneros who received the Outstanding Patron of the Arts award, noting her longtime support of Latin artists including early support Carmen Herrera, both thru acquiring her work and presenting it at her Miami institution, Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). -

Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 in & Around, NYC

2015 NEW YORK Association of Art Museum Curators 14th Annual Conference & Meeting May 9 – 12, 2015 Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 In & Around, NYC In addition to the more well known spots, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, , Smithsonian Design Museum, Hewitt, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Frick Collection, The Morgan Library and Museum, New-York Historical Society, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, here is a list of some other points of interest in the five boroughs and Newark, New Jersey area. Museums: Manhattan Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 (212) 288-6400 http://asiasociety.org/new-york Across the Fields of arts, business, culture, education, and policy, the Society provides insight and promotes mutual understanding among peoples, leaders and institutions oF Asia and United States in a global context. Bard Graduate Center Gallery 18 West 86th Street New York, NY 10024 (212) 501-3023 http://www.bgc.bard.edu/ Bard Graduate Center Gallery exhibitions explore new ways oF thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture. The Cloisters Museum and Garden 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tyron Park New York, NY 10040 (212) 923-3700 http://www.metmuseum.org/visit/visit-the-cloisters The Cloisters museum and gardens is a branch oF the Metropolitan Museum oF Art devoted to the art and architecture oF medieval Europe and was assembled From architectural elements, both domestic and religious, that largely date from the twelfth through fifteenth century. El Museo del Barrio 1230 FiFth Avenue New York, NY 10029 (212) 831-7272 http://www.elmuseo.org/ El Museo del Barrio is New York’s leading Latino cultural institution and welcomes visitors of all backgrounds to discover the artistic landscape of Puerto Rican, Caribbean, and Latin American cultures. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

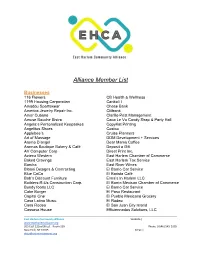

Alliance Member List

Alliance Member List Businesses 116 Flowers CB Health & Wellness 1199 Housing Corporation Cenkali I Amadou Sportswear Chase Bank America Jewelry Repair Inc. Citibank Amor Cubano Clarillo Pest Management Amuse Bauche Bistro Coco Le Vu Candy Shop & Party Hall Angela;s Personalized Keepsakes CopyKat Printing Angelitos Shoes Costco Applebee’s Cruise Planners Art of Massage DDM Development + Services Aroma D’angel Dear Mama Coffee Aromas Boutique Bakery & Café Deposit a Gift AV Computer Corp Direct Print Inc. Azteca Western East Harlem Chamber of Commerce Baked Cravings East Harlem Tax Service Barcha East River Wines Blooni Designs & Contracting El Barrio Car Service Blue CoCo El Barista Café Bob’s Discount Furniture Elma’s In Harlem LLC Builders-R-Us Construction Corp. El Barrio Mexican Chamber of Commerce Bundy foods LLC El Barrio Car Service Cake Burger El Paso Restaurant Capital One El Pueblo Mexicano Grocery Casa Latina Music El Rodeo Casa Rodeo El San Juan City Island Cassava House Efficiennados Solutions, LLC East Harlem Community Alliance Website | www.eastharlemalliance.org 205 East 122nd Street - Room 220 Phone | (646) 545-5205 New York, NY 10035 Email | [email protected] Euromex Soccer Play Up Studio Evelyn’s Kitchen Plaza Mexico Event by Debbie King Ponce Bank Fierce Nail Spa Salon Popular Bank GinJan Bros LLC Rancho Vegado Inc. Harlem Shake Result Media Team Gotham To Go R&M Party Supply Store GM Pest Control Rancho Vegado Corp Heavy Metal Bike Shop The Roast NYC IHOP The Rosario Group JC-1 Graph-X Sabor Borinqueño La Costeñito Grocery Sam’s Pizzeria La Reina Del Barrio Inc. -

New York Pass Attractions

Free entry to the following attractions with the New York Pass Top attractions Big Bus New York Hop-On-Hop-Off Bus Tour Empire State Building Top of the Rock Observatory 9/11 Memorial & Museum Madame Tussauds New York Statue of Liberty – Ferry Ticket American Museum of Natural History 9/11 Tribute Center & Audio Tour Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises (Choose 1 of 5): Best of New York Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum Local New York Favourite National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey - NEW in 2019 The Downtown Experience: Virtual Reality Bus Tour Bryant Park - Ice Skating (General Admission) Luna Park at Coney Island - 24 Ride Wristband Deno's Wonder Wheel Harlem Gospel Tour (Sunday or Wednesday Service) Central Park TV & Movie Sites Walking Tour When Harry Met Seinfeld Bus Tour High Line-Chelsea-Meatpacking Tour The MET: Cloisters The Cathedral of St. John the Divine Brooklyn Botanic Garden Staten Island Yankees Game New York Botanical Garden Harlem Bike Rentals Staten Island Zoo Snug Harbor Botanical Garden in Staten Island The Color Factory - NEW in 2019 Surrey Rental on Governors Island DreamWorks Trolls The Experience - NEW in 2019 LEGOLAND® Discovery Center, Westchester New York City Museums Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET) The Met: Breuer Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Whitney Museum of American Art Museum of Sex Museum of the City of New York New York Historical Society Museum Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Museum of Arts and Design International Center of Photography Museum New Museum Museum of American Finance Fraunces Tavern South Street Seaport Museum Brooklyn Museum of Art MoMA PS1 New York Transit Museum El Museo del Barrio - NEW in 2019 Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust Museum of Chinese in America - NEW in 2019 Museum at Eldridge St. -

1613-1945, El Museo Del Barrio in Collaboration with the New York Historical Society

Exhibition Review: NUEVA YORK: 1613-1945, el museo del barrio in collaboration with the New York Historical Society Susanna Temkin, Ph.D. Student, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University In the fall of 2009, el museo del barrio inaugurated its recently renovated galleries with the critically praised exhibition Nexus New York. A year later, the Manhattan museum plays host to Nueva York: 1613-1945, a show that in both its title and geographical focus recalls the earlier exhibition. Indeed, to a certain extent, the 2010 show might be considered a prequel of sorts, for whereas Nexus New York specifically focused on the significant dialog which took place in the city between Latin American and U.S. artists from 1900 to 1945, Nueva York steps back in time to examine the broader history that made such cultural interchanges possible. Seeking to illuminate the city’s deep roots with the Spanish-speaking world, Nueva York: 1613-1945 considers an expansive date range in its exploration of the historical, political, economic, and cultural connections linking New York, Latin America, and Spain. Curated by New York Historical Society guest-curator Marci Reaven (managing director of the educationally- driven organization City Lore), along with chief historical consultant Mike Wallace [professor at City University of New York and author of the best- selling history book Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (1998)], the show is the result of a collaboration between el museo del barrio and its neighbor across Central Park, the New York Historical Society. Stretching from the city’s colonial past until the end of World War II, Nueva York is organized both chronologically and thematically and addresses the lives and economic interests of the city’s earliest colonists, trade networks with Spanish-America, cultural encounters during the nineteenth century, political interests in various Latin American and Caribbean independence movements, and artistic exchanges during the first half of the twentieth century. -

The Art Museum As a Socio-Political Actor: El Museo Del Barrio and the Museo De Arte Y Memoria As Activist Cultural Productions in Their Respective Communities

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2011 The Art Museum as a Socio-political Actor: El Museo del Barrio and the Museo de Arte y Memoria as Activist Cultural Productions in their Respective Communities Erin C. Sexton College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Sexton, Erin C., "The Art Museum as a Socio-political Actor: El Museo del Barrio and the Museo de Arte y Memoria as Activist Cultural Productions in their Respective Communities" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 440. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/440 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 ® • ! ≤ - ≥ • ° ≥ ° 3 £ © ¨ © © £ ° ¨ !£≤ %¨ - ≥• §•¨ "°≤≤© °§ ®• - ≥• §• !≤• -• ≤©° ° ≥ ! £ © © ≥ # ¨ ≤°¨ 0≤§ £©≥ © ®•©≤ 2•≥•£©• # ©©•≥ Erin Sexton Acknowledgements: A very large —thank you“ to Alan Wallach, Silvia Tandeciarz, Sibel Zandi Sayek, Susan Webster, and Alexa Hoyne for their edits, i n s i g h t , a n d encouragement along the way. I am also indebted to Ingrid Jaschek and Susan Delvalle who gave their time, energy an d invaluable knowledge t o s u p p o r t this endeavor . —Revalorizing the culture from a democratic point of view implies empowering it as the stage for symbolic institutional mediations, where codes and identities interactively plot significations, values, and forms of p o w e r . -

Jewish Museums - a Multi-Cultural Destination Sharing Jewish Art and Traditions with a Diverse Audience Jennifer B

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) 12-2008 Jewish Museums - a Multi-Cultural Destination Sharing Jewish Art and Traditions With a Diverse Audience Jennifer B. Markovitz Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Markovitz, Jennifer B., "Jewish Museums - a Multi-Cultural Destination Sharing Jewish Art and Traditions With a Diverse Audience" (2008). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2398. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2398 Jewish Museums - A Multi-Cultural Destination Sharing Jewish Art and Traditions with a Diverse Audience By Jennifer B. Markovitz Dr. Susan K. Leshnoff, Advisor Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSEUM PROFESSIONS Seton Hall University December 2008 Abstract As American society becomes more diverse, issues of ethnic self· consciousness are increasingly prevalent. This can be witnessed by the national expansion and development of ethnic museums. At least twenty-five museums representing different ethnicities are located in New York City alone. These museums reach out to their own constituency as a celebration of heritage and culture. In an effort to educate others and foster a greater understanding and appreciation of their culture, they also reach out to a diverse multi-cultural audience. Following suit, Jewish museums attract a diverse audience representing a variety of religions and ethnicities. Jewish Museums - A Multi-Cultural Destination explores how this audience is reached through exhibition and education initiatives. -

August 9, 2021 RELIEF RESOURCES and SUPPORTIVE

September 24, 2021 RELIEF RESOURCES AND SUPPORTIVE INFORMATION1 • Health & Wellness • Housing • Workplace Support • Human Rights • Education • Bilingual and Culturally Competent Material • Beware of Scams • Volunteering • Utilities • Legal Assistance • City and State Services • Burial • Transportation • New York Forward/Reopening Guidance • Events HEALTH & WELLNESS • Financial Assistance and Coaching o COVID-19 Recovery Center : The City Comptroller has launched an online, multilingual, comprehensive guide to help New Yorkers navigate the many federal, state and city relief programs that you may qualify for. Whether you’re a tenant, homeowner, parent, small business owner, or excluded worker, this online guide offers information about a range of services and financial support. o New York City will be extending free tax assistance to help families claim their new federal child tax credit. As an investment in the long-term recovery from the pandemic, the federal American Rescue Plan made changes to the Child Tax Credit so families get half of the fully refundable credit—worth up to $3,600 per child—as monthly payments in 2021 and the other half as a part of their refund in 1 Compiled from multiple public sources 2022. Most families will automatically receive the advance payments, but 250,000+ New York City families with more than 400,000 children need to sign up with the IRS to receive the Credit. The Advance Child Tax Credits payments began on July 15, 2021 and most New Yorkers will receive their payments automatically. However, New Yorkers who have not submitted information to the IRS need to either file their taxes or enter their information with the IRS’ Child Tax Credit Non-Filer Sign-Up Tool For more information about the Advance Child Tax Credit including access to Multilingual flyer and poster—and NYC Free Tax Prep, visit nyc.gov/TaxPrep or call 311. -

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

Virtual Museum Mile Festival Tuesday, June 9, 2020, 9 Am to 9 Pm

Press contacts The Jewish Museum, [email protected] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, [email protected] Museum of the City of New York, Robin Carol, [email protected] VIRTUAL MUSEUM MILE FESTIVAL TUESDAY, JUNE 9, 2020, 9 AM TO 9 PM Follow #VirtualMuseumMile for a Variety of Fun Programming from The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Neue Galerie New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; The Jewish Museum; Museum of the City of New York; El Museo del Barrio; and The Africa Center New York, NY, May 28, 2020 – Eight New York City museums are joining together to create the first ever day-long virtual Museum Mile Festival on Tuesday, June 9, 2020, from 9 am to 9 pm. Throughout the day, each museum will host live and pre-recorded programs, virtual exhibition tours, live musical performances, and activities for families streamed across their respective websites and social media platforms. Culture enthusiasts from around the world will now be able to join New Yorkers, during this unprecedented moment, and enjoy the festival. The day’s offerings will be listed on each participating museum’s website. In addition, audiences can follow the hashtag #VirtualMuseumMile on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook for cultural happenings throughout the day. The eight institutions participating in this highly successful collaboration are The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Neue Galerie New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; The Jewish Museum; Museum of the City of New York; El Museo del Barrio; and The Africa Center. Museum of the City of New York; El Museo del Barrio, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art are members of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG), a diverse coalition of 34 nonprofit museums, performing arts centers, historical societies, zoos, and botanical gardens in New York that share a private-public partnership with the City and reside within City-owned property.